The Secret History Of The Devil

The Devil may seem like a pretty straightforward concept upon first glance. He's the personification of evil and, for monotheistic believers, the archfiend who opposes all of the goodness and glory of God. It follows that, if God is a sort of eternal force or personage, then so, too, must the Devil be his constant opponent in the cosmic battle between good and evil — and for your very soul.

But the real history of the Devil as a concept within Christianity and other Abrahamic religions is far more complicated. For one, the idea of a single, ultra-evil Satan didn't exist for early Jewish people, despite what simplified Bible stories of the Old Testament may have you believe. In fact, he doesn't arise until well into the New Testament. And much of what we take granted for the Devil on a cultural level, from the fallen angel backstory to that striking all-red look, is the accumulation of many years of folklore, misattribution, and outright fiction.

So, who or what is the Devil, really? Is he a supreme evildoer? A compatriot of God? A trickster? A monster? A hunky anti-hero? An object of worship? Could he be all of those things at once, or even something else entirely? Maybe it's time to set your preconceived notions to the side, at least for the time being. This is the secret history of the Devil.

There isn't really a Devil in the Hebrew bible

Wait, wasn't Satan in the Garden of Eden, tempting Adam and Eve from the very beginning of humanity? Fair enough, given that many interpretations of Old Testament stories pretty explicitly bring in the Devil, from Genesis to Job. But a close reading of that text reveals some serious narrative complications.

Instead, as the Biblical Archaeology Society points out, the presence of the Devil is a modern gloss applied on top of these ancient texts. The talking serpent in the Garden of Eden is definitely creepy and causes lots of trouble, to be certain, but nowhere in Genesis is the creature explicitly linked to Satan. Frankly, at the time that the text was written, there was no concept of a single, powerful adversary opposing God. The Devil, in short, didn't exist yet.

As for the story of Job, the man beleaguered by tragedy after tragedy as he's caught in a divine tug-of-war between good and evil — well, that's not quite right, either. Yes, the story makes it clear that God wants to test Job's faith, but Satan isn't there as some sort of divine betting partner. Instead, as The New Yorker reports, the figure referred to as "Satan" is more accurately translated as "adversary." Basically, the "Satan" of this story is kind of like a prosecuting attorney who's attempting to prove that Job and the rest of humanity are fundamentally flawed. And that being is still very much in God's employ.

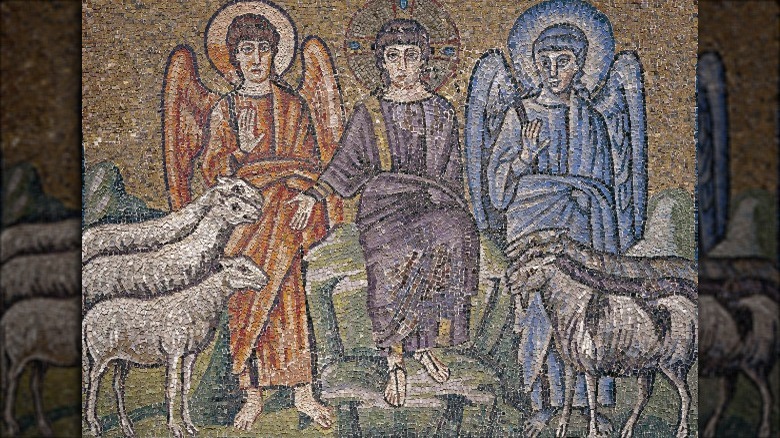

The very first image of Satan might be in Ravenna, Italy

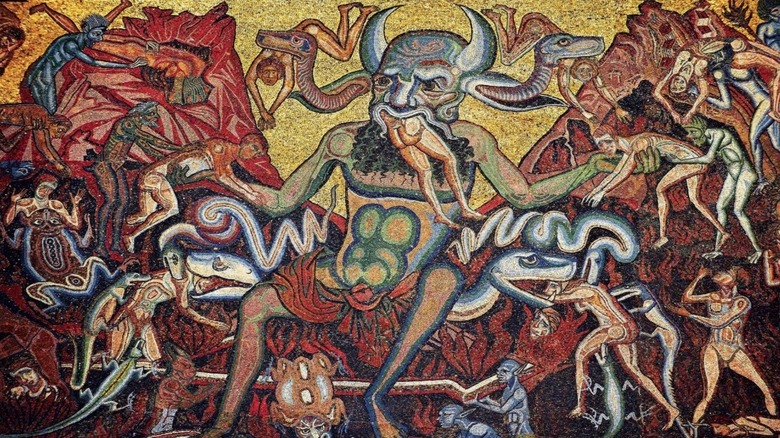

If you're looking for depictions of the Devil or even just devils in general, you probably start your search by seeking out images of inhuman creatures. You know the classic image, don't you? It's all horns, pointy tails, cloven hoofs, and red skin. But, according to National Geographic, that frightening image of Satan arose in the Middle Ages. Before that, there was either no concept of Satan to require an image or the arch evildoer would have looked very, very different.

Take the Satan seen in a 6th century mosaic in the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy. According to LiveScience, this is typically considered the first-ever depiction of the Devil. In one section of the mosaic, Christ is seen sorting out the righteous and the sinners at the Last Judgement, represented by sheep and goats respectively. Each flock is overseen by an angel. To Christ's right are the good sheep and a red angel. To the left, behind the goats, is a blue-clad angel who's apparently in charge of the evildoers, perhaps getting ready to herd them off to hell.

But this blue Satan doesn't have horns or a tail. Instead, he seems just as much like the angel to Christ's right as any other, complete with a halo, wings, and a beatific expression. Is he Satan at all? Perhaps, at least as a heavenly functionary, but it's far removed from our modern understanding of the Devil.

Pagan gods may have inspired the animalistic Devil

So, if the earliest depictions of the Devil show him as an angel like any other, how did we get to the horned and hoofed creature of today? That may be thanks in part to early Christian leaders who specifically wanted to make the old pagan gods look demonic in an attempt to bolster their own new religion by contrast.

If you're still not so sure, consider Bes, the ancient Egyptian protective deity whose admittedly ugly face can be seen on all manner of pre-Bible artifacts. Per the BBC, Bes was originally depicted as a short-statured, grotesque figure, whose image was meant to scare off things like childbirth complications, while also representing good times like partying, music, and booze. As a result, Bes shows up seemingly everywhere, including eating utensils, beds, temple buildings, makeup jars, and little amulets. Eventually, as Christianity grew and began to set down roots in Egypt, Bes seems to have been linked up with traditional Devil imagery. It may be no mistake that early images of the Devil were blue and many pagan amulets were finished with a blue glaze, says the BBC.

But it wasn't just Bes who may have been targeted as demonic inspiration. Over in areas with Greek and Roman influences, the half-goat, half-human nature god known as Pan may have lent his horns and general animalistic look to the Christian devil, too (via National Geographic).

How did Lucifer become the Devil?

Very often, tales of the fallen angel known as Lucifer are directly linked to the Devil. It makes sense, after all, especially if you believe that Satan needs an origin story. And what better drama than a good boy gone bad? As most versions of the tale go, Lucifer was a beautiful, perfect member of the heavenly host who got it in his head to rebel against God. Inevitably, God finds out and Lucifer, along with his cronies, is cast out of Heaven and into the underworld.

If you look in the Bible, the Book of Isaiah does indeed mention Lucifer. Then again, according to Bible.org, that might change depending on the translation you're using. In the King James Version of the Bible, Isaiah 14:12 reads: "How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! How art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations!" Yet, "Lucifer" is likely a descriptor better translated as "morning star." And it may have been in reference to a human ruler or non-Christian god, rather than Satan himself.

Then, there's John Milton, author of "Paradise Lost." The 1667 epic poem has a lot to do with connecting Lucifer and Satan in the modern imagination (via National Geographic). Milton's magnum opus not only did that, but also painted the fallen adversary as a sort of Romantic anti-hero, though he probably wouldn't go quite so far as to say he admired the archfiend.

The Devil wasn't always red

In modern Western thought, Satan is usually a large creature with horns and cloven hooves, sometimes even depicted with goat-like lower limbs. Most importantly, he's red, now a color commonly associated with hellfire and demons. But that wasn't always so. The depiction of Satan in a 6th century mosaic in Italy shows him in blue, while other medieval artworks also sport a very blue Devil in the midst of hellish scenes (via Lessons From History).

Meanwhile, the Center for Studies in Oral Traditions reports that, in the folklore traditions of Europe, Satan and his minions are associated with a seeming rainbow of colors, from black to green to yellow. Even Tituba, the enslaved women whose testimony helped to kick off the panic of the Salem Witch Trials in 1692 Massachusetts, referred to devilish creatures that were red, yellow, black, accompanied by a white-haired man ominously dressed in black (via Smithsonian Magazine).

The completely red devil doesn't appear to have come along until later, with Satan making his debut in red tights during the mid-19th century, per LiveScience. That popular depiction may have its roots in Charles Gounod's opera, "Faust," where the diabolical Mephistopheles character belted out his songs while wearing red tights.

The Devil may exist to answer a thorny theological problem

If the Devil wasn't around since the beginning of Judeo-Christian theological thought, then where did he come from? As History points out, it may have something to do with the diaspora of Jewish people living in Babylonia. That's where they came into contact with Zoroastrianism, which many argue is the first monotheistic faith in history. The tenets of the ancient Persian religion include a belief in a single god, Ahura Mazda, as well as the idea of divine judgement and separate afterlives for good and evil people. And, maybe not coincidentally, Ahura Mazda has an evil nemesis known as Ahriman, who keeps busy causing trouble for humans. According to the World History Encyclopedia, it's very possible the Ahriman set the stage for Satan in both Judaism and Christianity.

But the Devil may still be causing more trouble than he was meant to solve. Consider the "problem of evil," for instance. Essentially, the basic nature of God as determined by many religious groups makes the existence of evil a serious issue, per the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The line of questioning goes that, if God is supposed to be entirely good and just, then who's causing all the evil in the world? If it's God, then that damages the idea of His inherent righteousness. A Devil may fill that role, but his existence independent of God also potentially damages the image of an all-powerful and good deity.

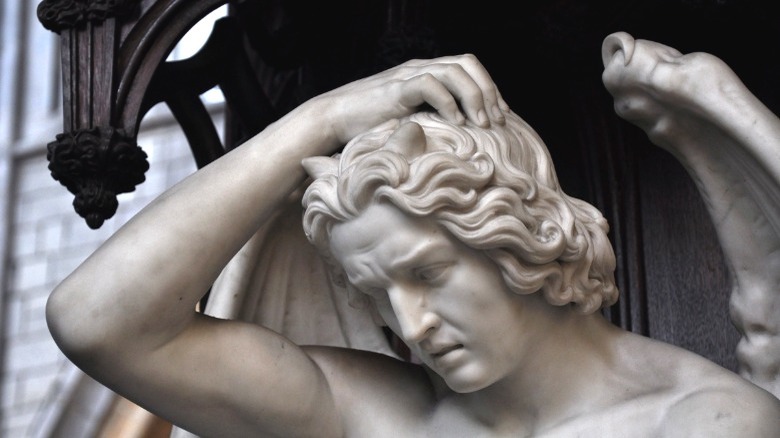

The Devil's beauty made things even more complicated

Medieval devils and Satan especially were meant to be repulsive creatures. But then the Romantics came along and made Satan beautiful.

Really, the rise of the gorgeous devil wasn't all the fault of 19th century European artists with a flair for the dramatic. There's always John Milton to blame. He arguably started the trend of the brooding, hunky Satan in the 17th century with his epic poem, "Paradise Lost," which later artists like William Blake turned into artistically minded eye candy, per The Atlantic. Blake himself would eventually hail Lucifer as a kind of savior (via History). Creepy, animalistic devils still abounded in frescos and on canvases, but the precedent was set.

In the 1830s, Belgian sculptor Joseph Geefs was commissioned to create a marble statue of Lucifer for the cathedral of Liège. But, according to SyFy, the statue was distractingly beautiful, to the point where some worried that it was leading younger parishioners astray. Joseph's statue was taken away and his older brother, Guillaume, who also happened to be a sculptor, was commissioned to make the replacement. However, Guillaume's entry, though technically more clothed than his brother's work, still featured a gorgeous, bare chested, muscle-bound Lucifer with nicer hair than the first sculpture. Whether Guillaume's work was deemed acceptable enough or the cathedral's budget ran out, the church decided to keep this statue, where it can still be seen behind the pulpit to this day (via Atlas Obscura).

Protestants changed the Devil for their own means

It's possible that one of the most seismic shifts in all of Christian history is the schism that resulted in a breakaway group of believers collectively known as the Protestants. Breaking with hundreds of years of Church doctrine and tradition, Protestant figures such as Martin Luther led the way to a new and distinctly different way of belief (and a new avenue for in-fighting amongst Christians as a whole). And, as with so many other parts of what was once believed to be unassailable belief, the Protestants changed Satan.

For one, as the Journal of the Historical Association reports, the Protestants found the Devil to be a useful marketing tool. It wasn't quite so crass as later efforts to use Satan as a mascot for, say, deviled ham products, but some Protestants did use his frightening image in an attempt to bring people over to their side. If, as they said, the Devil was part of the Catholic Church, wouldn't you want to jump ship and join the Protestant side?

Even Daniel Defoe, the 18th century author of "Robinson Crusoe," got in on the Protestant deployment of the devil with his 1726 polemic, "The Political History of the Devil." Per the British Library, Defoe was a Protestant dissenter who used this work to further his own views (like the belief that the Devil was a real, physical being) and to sully the name of the Catholic Church.

People have been worshipping the Devil for longer than you think

It's easy to understand why a darkly compelling character like the Devil could become the object of worship amongst some who find themselves drawn to contrary and rebellious figures. Who embodies that more than the modern Satan, who's often painted as an antihero willing to stand up to God himself?

But devil worship has been around for far longer than the swooning, Romantic Era Lucifer. In fact, according to the Loyola University Student Historical Journal, even medieval people — many of whom should have been scared out of their jerkins by the hideous devils painted on their church walls — were known to occasionally worship the Devil, according to some accounts. Yet, it appears that a lingering combination of old pagan beliefs, combined with some fear of breakaway sects like the Gnostics, meant that church leaders were sometimes frantically worried about Devil worshippers in their midst.

More overt Satanic worship came to the fore in the 20th century with the rise of Aleister Crowley, History reports, though Crowley's use of devilish imagery was more symbolic and also likely meant to shock more conventional people. Then, in the 1950s and 1960s, showman and musician Anton LaVey turned his occult workshops into the Church of Satan. It's very possible that LaVey was more interested in the spectacle than genuine belief, but his Church gained wide publicity and may have led directly into the Satanic Panic hysteria of the 1980s and 1990s.

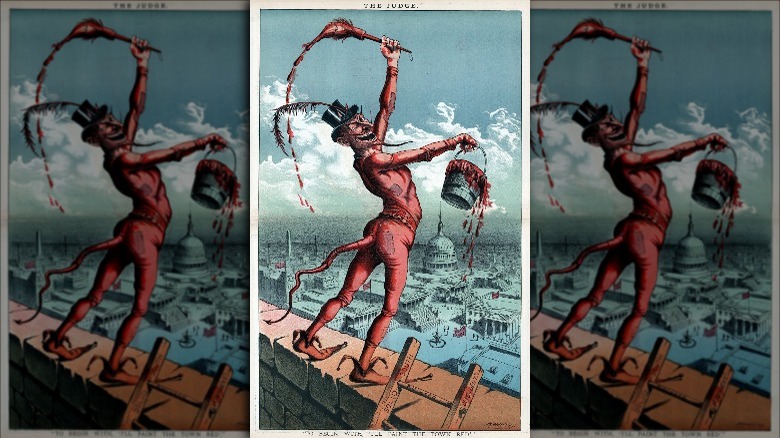

Satan has long been used as a political tool

As a figure who represents ultimate evil, it's no wonder that the Devil was eventually co-opted as a political tool. During the medieval era, poet Dante Alighieri famously used Hell and Satan in "The Divine Comedy" to punish and lampoon his political enemies on the page, according to Columbia University's Digital Dante project. Dante, who was exiled from his home city of Florence for backing the wrong political cause, clearly had an axe to grind.

So, too, have others who deployed Satan and his minions as political symbols. Numen reports that Satan was deployed as a rallying symbol for socialists in the 19th century, who wanted to break the bonds of church and capitalism — and who better to represent their cause than the ultimate bond-breaker? It was also a convenient shock tactic meant to raise the profile of their cause in a decidedly more religious and conventional era.

And, of course, before Dante or socialists came along to co-opt the image of the Devil for their own purposes, there was the Christian Church. Per PBS, the Book of Revelation written by John of Patmos can easily be read as political propaganda against Rome. Its talk of a seven-headed beast references the pagan Roman emperor and, naturally, the Satanic forces at his disposal are those of real-world Rome. John may have called it "Babylon," but most of his readers would have readily understood it as the devious realm of Satan himself.

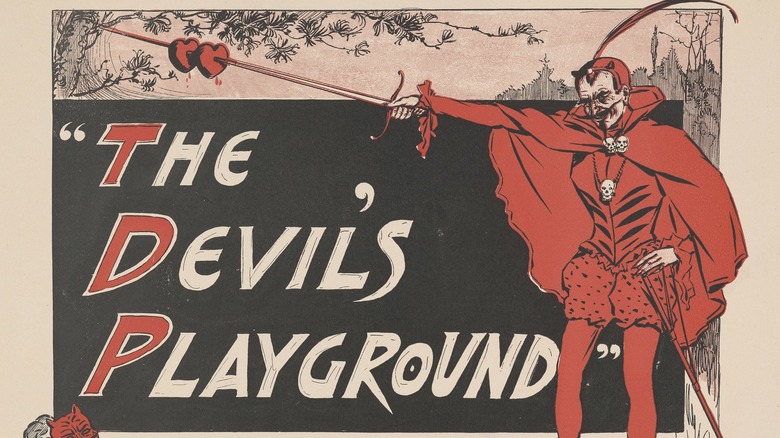

A ridiculously dressed devil reflects modern changes in religion

Quite a few modern iterations of the Devil now have him as a cartoonishly evil figure, hardly the hulking menace seen in medieval frescoes or the smoothly alluring Lucifer figure promoted by John Milton or William Blake. What happened to the Prince of Darkness?

As Racked reports, it's all Faust's fault. According to German folklore, Faust was an alchemist who made a deal with the Devil for fame and fortune. The tale made its way onto the stage with Goethe's "Faust," as well as English playwright Christopher Marlowe's play, "Doctor Faustus." The tale became especially popular in 1859 with the premiere of Charles Gounod's opera, "Faust." It's here where Mephistopheles, the devilish character who steers Faust awry, appears in an all-red outfit. The eye-catching look caught on and eventually trickled down to other stage and film productions, as well as cheeky marketing campaigns for things like decaf coffee and cigars.

But the appearance of this neutered Devil wouldn't be possible if it weren't for a massive shift in how people thought about life and religion. Consider the Renaissance and the 18th century Enlightenment, which progressively brought about less literal interpretations of evil. If the Devil wasn't literally a hog-faced, horned being or some similar monster, then what was evil, really? Perhaps it was something less obvious, enshrined in your own society and perhaps even yourself. And, with that shift, it became easier to ridicule the previously terrifying specter of the Devil.