The Bizarre Story Of The Poet Who Claimed To Be King Of Poland

The word "eccentric" is usually thrown around in a fashion that suggests its target is superficially strange — perhaps physically, perhaps behavior, perhaps both — but that at the end of the day they are harmless, benign beings who just for one reason or another don't quite fit into society. Often, such figures find themselves entangled in their own singular, personal passion projects, which consume them while keeping them separate from world events. Sometimes, however, a true eccentric, who sees the world through their purely individualistic vision, breaks out into the world and begins to try and reshape it from the margins.

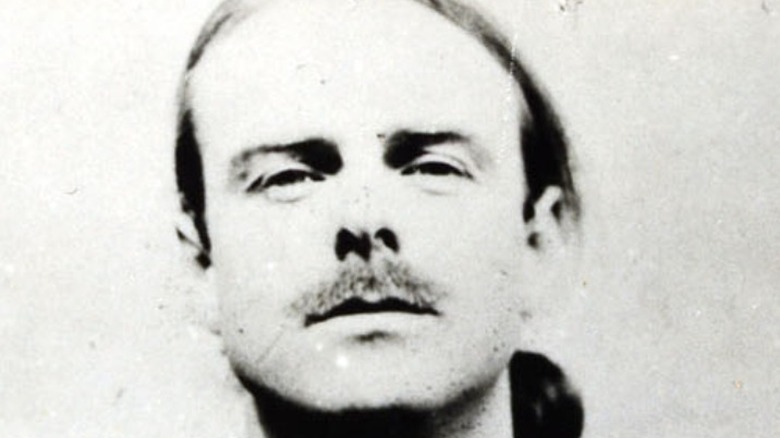

And so is the case of New Zealand-born Count Geoffrey Wladislas Vaile Potocki de Montalk (October 6, 1903–April 14, 1997), a poet of some renown in his homeland who caused a stir on his arrival in London thanks to the perceived scandalous nature of his publications, and who became a notorious fringe figure throughout World War II and beyond.

Count Geoffrey Potocki de Montalk: would-be poet King

Count Geoffrey Potocki de Montalk certainly was descended from the aristocracy, though his father, architect Robert Wladislas de Montalk, had rescinded his title on his arrival in New Zealand decades earlier, as was typical for those emigrating to lands where such ancestral titles were irrelevant. According to academics Graham Macklin and Craig Fowlie, whose paper, "The fascist who would be king," was published in the journal Patterns of Prejudice in 2019 (posted at Taylor & Francis Online), the young Potocki de Montalk worked in New Zealand as a milkman, while exploring paganism and harboring growing literary ambitions among a group of budding Kiwi poets — much to the chagrin of his respectable family.

Realizing that to make his name as a man of letters he had to head to Europe, Potocki de Montalk boarded a boat to England — abandoning his wife and child in the process — and on his arrival in London in 1927 announced himself as "The rightful King of Poland, Hungary and Bohemia, Grand Duke of Lithuania, Silesia and the Ukraine, Hospodar of Moldovia and High Priest of the Sun" (per Macklin and Fowlie).

Count Potocki's bohemian life in London

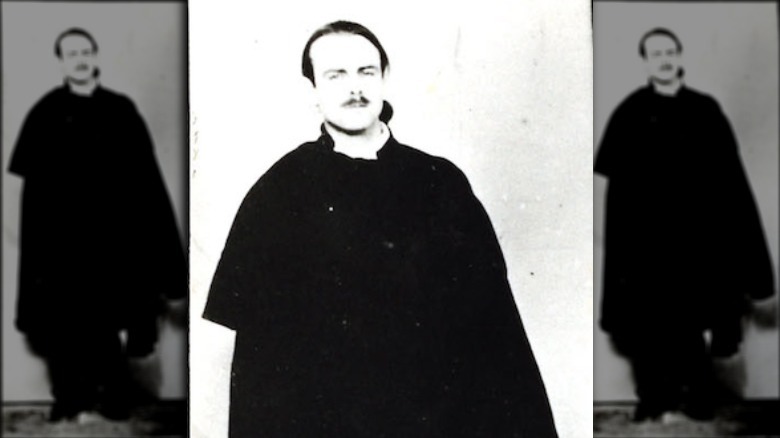

When you freshly arrive in London spouting poetry and claiming to be King of Poland, it's bound to turn heads. And not only in his behavior was 24-year-old Count Potocki de Montalk eccentric. The pagan poet also drew considerable attention for his style of dress, which typically consisted on a long black cloak and sandals, according to the critic Donald Kerr (via JSTOR), with his blond hair worn unusually long for the period. As such, he looked like a figure who had just jumped out of a medieval painting.

Potocki de Montalk quickly integrated himself into the local London literary scene, where his eccentricities made him a memorable figure. He was, as his cousin and biographer Stephanie de Montalk puts it in the book "Unquiet World," a "charming young poet," and as such attracted a circle of like-minded friends and collaborators, as well as numerous patrons who were willing to support him in his literary ambitions. Though still a fringe figure, Potocki de Montalk succeeded in having his poetry published in numerous newspapers and magazines, according to History@Kingston. He seemed to be living the bohemian dream.

Count Potocki was found guilty of obscenity

The young poet's life took a dramatic turn when he approached a London printer to publish some translations of sexual verse by the poets Paul Verlaine and François Rabelais, as well as poetry of his own creation, including one, titled "Here Lies John Penis," which was just as explicit as the title suggests.

The printer reported the content of the Count's proposed pamphlet to the police, according to Macklin and Fowlie, and the young poet soon found himself in court at the Old Bailey, defending himself against charges of obscenity. A documentary made about the case describes it as "the most extraordinary obscenity trial of the century, [that] changed the course of [Potocki's] life as a peace-loving and romantic poet" (via YouTube).

Potocki's first appearance before the judge became something of a circus. He was dressed, as always, in cape and sandals, and refused to swear on the Bible, instead telling the court that he was a follower of Apollo the Sun God, and giving the judge what appeared to be a fascist salute in the style of "Julius Caesar or Mussolini."

The eccentricities that won the Count many London friends were his undoing in the courtroom. Macklin and Fowlie claim that the judge in question was a "conservative traditionalist," who obviously took exception to the poet; Potocki himself later argued that the judge illegally "bullied" the jury into a guilty verdict (via Youtube), who sentenced him to six months in prison.

The dark side of Count Potocki de Montalk

Count Potocki de Montalk emerged from prison jaded, combative, and more strident in his unusual beliefs.

Potocki's claim to the throne of Poland may appear, like his dress sense, to be a harmless eccentricity, and was surely considered so by many of his friends and supporters who at the time of his imprisonment included such famous figures as Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, and H. G. Wells, according to Macklin and Fowlie. But as they point out, the Count also believed unwaveringly in the "divine right of kings," which made him sympathetic to the fascist movement that was sweeping through Europe at the time. On his release from prison, Potocki was given funds to set up a printing press, and as a result he would come to play an instrumental role in disseminating fascist publications.

Potocki established a magazine, "The Right Review," a fiercely monarchist and fascist journal. The publication's opening editorial stated: "We intend to prove that such government is intensely beneficial to the whole human race including the lowest races of mankind." Through the magazine, Potocki aligned himself with several prominent fascist groups, showing support for both General Franco and British fascist Oswald Mosley (pictured). Potocki was vocal in his wish that Adolf Hitler would emerge victorious in World War II — he reportedly held a party on the occasion of Hitler's birthday — and was widely condemned as a traitor thereafter.

A worthwhile work? Potocki's 'Katyn manifesto'

Macklin and Fowlie are damning in their exposure of Count Potocki de Montalk as an "enabler" of fascism, who used his assets as a printer to disseminate dangerous right-wing propaganda for almost half a century.

One of Potocki's right-wing tracts did, on the surface at least, have political merit. Using information he had gleaned from Polish contacts, Potocki sought to expose the fact that the Katyn massacre — a horrifying incident in 1940 in which 22,000 Polish military officers, servicemen, and intellectuals were mass executed — was committed by the Soviet Union, rather than Nazi Germany, as had been the official line of the British government who had recently forged an alliance with the USSR. However, Macklin and Fowlie argue that, like almost all of Potocki's political activity, the Count's desire to expose the perpetrators of the Katyn massacre derived, once again, from his underlying desire for the Polish throne — put simply, Potocki saw Nazi Germany more likely to reform the Polish monarchy than the communist Soviets, and, though his findings were later proven true, his use of them was undoubtedly opportunistic.

Potocki remained on the fringes of the literary establishment throughout his long life, though he continued to publish various poetical works and political and social treatises — he even revived "The Right Review," and published new editions as late as the 1970s. He died in Brignoles, France, in 1997, aged 93.