The Untold Truth Of Rush

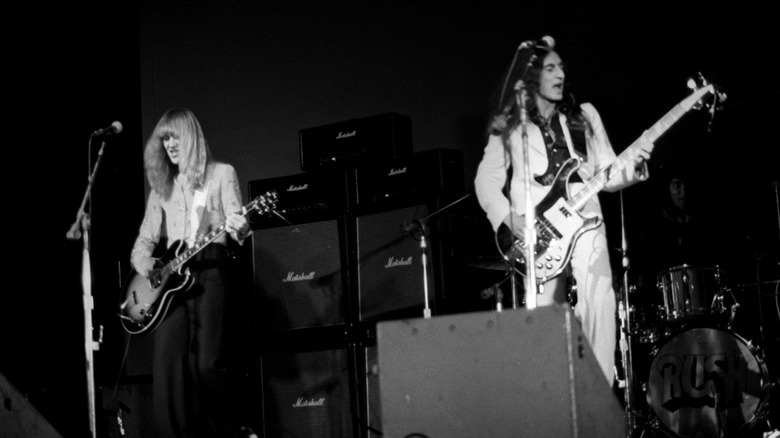

Rush is one of the most unlikely bunch of rock legends ever known. Three guys from Canada writing intricate, complex songs with erudite, philosophy-infused lyrics and a lead singer whose octave range defies reality? If you'd suggested back in 1968 that these were the ingredients for a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band of legendary status and 14 platinum-selling albums, no one would have believed you.

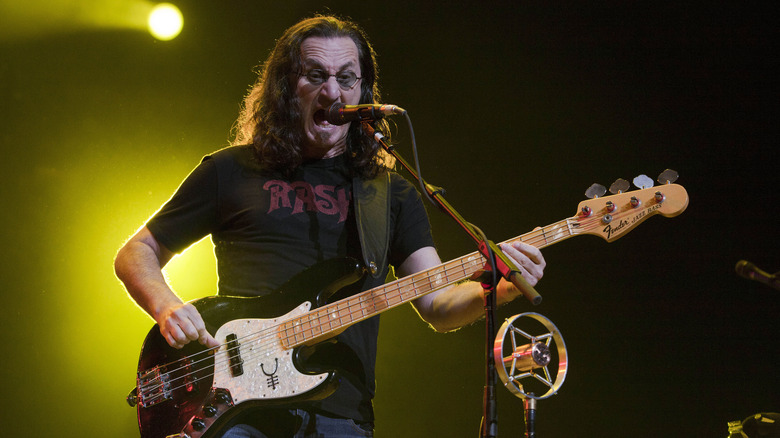

Geddy Lee, Neil Peart, and Alex Lifeson proved everyone wrong, however. Over the course of nearly 50 years, Rush was one of the most reliably popular hard rock groups in the world. They had 12 Top 10 albums on the Billboard 200, seven Hot 100 charting songs, and one Top 40 hit. They put on elaborate, energetic live shows, somehow generating an incredibly deep, rich sound from just three musicians while ensuring the lifelong loyalty of their fans.

Rush carved out a unique place for themselves in the music world, with a sound that defied expectations and genre limitations. They infused their hard-rock sound with synthesizers and reggae beats, they pushed the creative envelope more than once, and yet they never lost sight of the ultimate goal—to entertain. Despite their success and fame, Rush remains an enigma in many ways. Here's the untold truth of Rush.

Neil Peart wasn't an original member of Rush

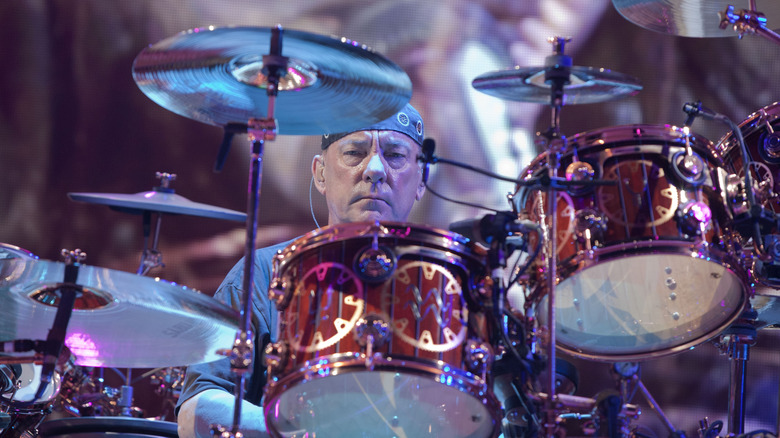

If there's one thing even non-fans know about Rush, it's that their drummer, Neil Peart, was considered one of the greatest drummers in the history of modern music. Rolling Stone ranks him at #4 on its 100 greatest drummers of all time list, surpassed only by Ginger Baker, Keith Moon, and John Bonham—which is pretty good company. Originally modeling his drumming on Moon's frenetic, unconventional style, Peart ironically became known as "The Professor," a drummer who brought precision and intricacy to every song.

As noted by NPR, Peart also became the band's chief lyricist, writing most of the words for their songs and introducing an intellectual and verbose sensibility to rock and roll. In other words, Peart was essential to Rush—without Peart, Rush would have been a very different band.

So it's key to note that Rush almost was that different band. As explained by Ultimate Classic Rock, when formed in 1968 the band's drummer was John Rutsey, a childhood friend of Alex Lifeson. Rutsey was the band's timekeeper until 1974, co-wrote their debut single and played on the band's first record, which included the band's first breakthrough hit with "Working Man." According to Geddy Lee, Rutsey didn't like the touring life, and wasn't up for the type of drumming Lifeson and Lee wanted, so he left the band on amicable terms—paving the way for Peart to join and change the band's history.

Geddy Lee wasn't an original member, either

Even folks who don't like Rush are familiar with Geddy Lee's supernaturally high-pitched singing voice. The exact opposite of the traditional growl of a rock band's frontman, Lee's piercing voice proved to be the secret ingredient for Rush's unique blend of power chords, polyrhythms, and erudite lyrics—but it was almost an entirely different sound.

As noted by Rush is a Band, when Rush formed in 1968 its bassist and lead singer wasn't Geddy Lee—it was Jeff Jones. Jones only lasted long enough with the band to play their first paid gig, though. According to Louder, the band scored a second paying gig the next week—but Jones had a commitment to another band he was in and couldn't make it. Desperate to keep their gig, guitarist Alex Lifeson called his friend Geddy Lee to step in and replace Jones—and Rush history was made.

Jones did okay, however. First, he joined the Christian band Ocean, which scored a hit in 1971 with the song "Put Your Hand in the Hand." Later, he joined the band Red Rider, which scored a hit in 1981 with "Lunatic Fringe." Considering how different Jones' playing and singing style is from Lee's, it's fascinating to think how different Rush might have been if Jones had been available for that second gig.

Geddy Lee became a bassist because no one else wanted to

Geddy Lee is probably one of the most famous bass players of all time. In fact, Rolling Stone ranks him as the 24th best bass player ever, noting that his playing acts as a bridge between the bass pioneers of the 1960s and the aggressive styles of more modern players. Lee is so associated with the instrument—and as he told Rolling Stone in an interview, actually enjoys playing bass more than he enjoys singing—that it's surprising to learn that Lee didn't want to be Rush's bassist.

As he explained to Rolling Stone, Lee was playing guitar in another band and wanted nothing to do with the bass, thinking "nobody chooses to be a bass player." Far Out Magazine notes that bass is commonly considered a "dull" instrument in rock music, and it's certainly true that most of the attention goes to the lead singer and guitarist in a band, usually, so Lee's attitude is understandable.

But when the band's bass player was forbidden to play by his mother, someone had to take on the bass playing duties, so it fell to Lee. He had to borrow money from his own mother to buy his first bass guitar—but lucky for music lovers he did, because Lee has crafted some of the most intricate and recognizable bass lines in rock and roll history.

There's Objectivism in their lyrics

Drummer Neil Peart has been Rush's main lyric-writer for most of their career. Peart's thoughtful, intellectual lyrics have explored many philosophical issues, but one of his chief obsessions was free will and individuality. If you're familiar with Ayn Rand and her own philosophical system known as Objectivism, it's not terribly surprising that Peart's lyrics often appeared to overlap with Objectivist teachings, causing some controversy.

You can see why: According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, Objectivism embraces a concept known as "ethical egoism" that argues any action is morally correct if it benefits the individual. This has made Objectivism attractive to many far-right politicians who reject the principle that the government has the authority to dictate their behaviors for the overall good of society.

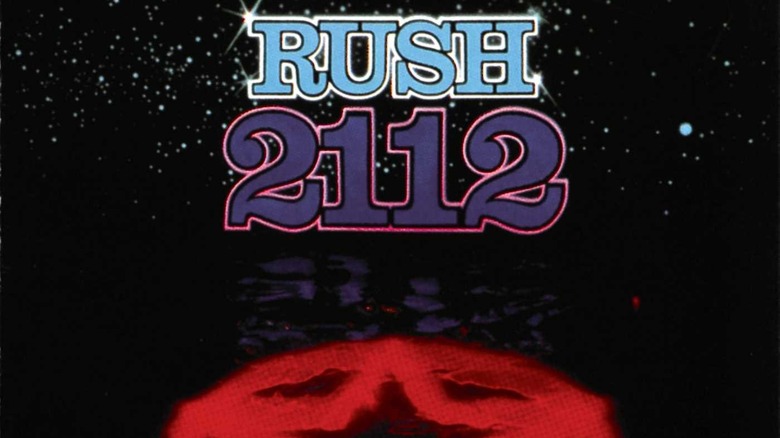

As noted by Open Culture, Peart infused much of Rand's teachings into the first three albums he recorded with Rush. And according to The Guardian, Rush's seminal 1976 album "2112" was controversial in some quarters because its themes of individual struggle against society echoed Rand's teachings, which are often associated with extreme far-right politics. Bassist Geddy Lee acknowledged that the band was influenced by Rand but insisted that it had nothing to do with politics—what resonated with the band were her ideas about artistic struggle and the refusal to compromise.

Rush refused to bend to label pressure

As told by Ultimate Classic Rock, Rush has always forged their own path. In 1973, they had a catalog of original songs and lots of experience playing live. Even though they were courted by record labels, they opted to fund their debut album themselves—and even formed their own record label to release it on. That should have been a recipe for obscurity, but their song "Working Man" caught on with U.S. radio, which led to a deal with Mercury records.

Unfortunately for Rush, their second ("Fly by Night") and third ("Caress of Steel") albums didn't maintain that level of success. As noted by Sharp Magazine, in fact, "Caress of Steel" was a certified "commercial failure." Those albums represented an increasingly progressive and experimental sound, and Mercury Records demanded that for their next album Rush concentrate on writing something catchier, shorter, and less experimental in order to sell more records.

But as reported by The Chicago Tribune, Rush instead decided that if their career was over, it was going to end on their own terms. Instead of trying to please their label, they recorded "2112"—one of the densest, most progressive rock albums of all time, complete with a nearly-incomprehensible sci-fi story as a concept. "2112" turned out to be the turning point: It went multi-platinum, a smash hit that ensured Rush the freedom to record whatever they wanted.

Rush changed their sound

The year 1976 was the culmination of a period of intense creativity for the band. The three albums that followed their debut—"Fly by Night," "Caress of Steel," and "2112"—each delved deeper and deeper into progressive, experimental rock. This meant concept albums, long compositions—the title track from "2112" is more than 20 minutes long—and intricate arrangements.

As noted by NPR, there was a lot of pressure on the band while recording. The record label pressured them to return to their earliest sound in a bid for some radio airplay. The band was touring non-stop, and writing songs in dressing rooms and the backs of cars. After "2112" became a huge success, Rush had the freedom to keep doing what they wanted—which meant their next two albums, "A Farewell to Kings" and "Hemispheres" were similarly structured, with long, multi-part compositions and grueling recording sessions.

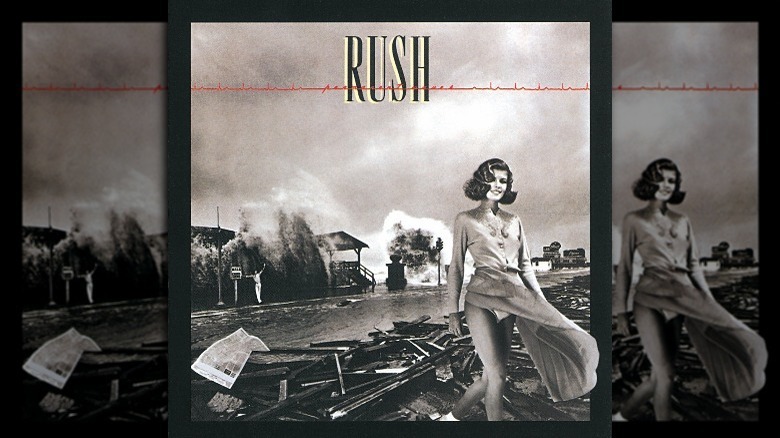

As Louder reports, by 1980 the band was ready to take a step back from that approach—and totally change their sound. Any band selling millions of records to devoted fans would be considered crazy to play with their sound, but Rush managed it—their 1980 album "Permanent Waves" was a huge hit, the debut single "Spirit of the Radio" debuted at #13 on the UK charts, and established a template of catchier, shorter songs the band would explore successfully for years to come.

Neil Peart struggled to play his old stuff—because he was too good

One aspect of Rush as a band that made them stand apart from their peers was not just a willingness to experiment—they famously ignored label pressure to record one of the most progressive rock albums of all time—but an openness to new ideas. By the 1980s, Rush had established itself as one of the most popular rock bands around, but its three members continued to expand their skills and try new things. For example, Fender tells us that bassist Geddy Lee developed a whole new style of right-handed picking in the early 2000s after he met Les Claypool of the band Primus and observed some of his technique.

Neil Peart is widely considered to be one of the greatest drummers of all time, but his style of playing and his capabilities evolved and grew over time. When he initially auditioned for Rush he was likened to the chaotic style of Keith Moon, but by the time the band was releasing classics like "Tom Sawyer" he'd developed an intricate, methodical style that combined power with precision. In fact, he'd gotten so good at drumming he told Rolling Stone he had trouble playing some of the band's oldest material, saying that his younger self did stuff "I would never do," adding, "Immature is the right word. I know I have a mature, hard earned mastery of the instrument now."

They almost retired in 1998

By the mid-1990s, Rush were well-established superstars in the rock world. They'd sold millions of albums and were fixtures on rock radio everywhere, and the three albums they released in that decade—"Roll the Bones," "Counterparts," and "Test for Echo"—were well-received and enjoyed strong sales. The band was defying the conventional narrative of an aging rock band running out of ideas.

Then, as noted by Rolling Stone, in 1997 drummer and lyricist Neil Peart suffered two incredible tragedies within a few months. First, his daughter, Selena, died at age 19 in a car accident while driving to university. A few months later, his longtime companion and Selena's mother, Jackie Taylor, succumbed to cancer—although Peart diagnosed it as a broken heart in his autobiography.

Devastated from his loss, Peart informed his bandmates Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson in 1998 that they should "consider me retired," then left for a long solitary motorcycle ride. The band was essentially over at that point—there was no Rush without Peart's drumming and lyrics. But Peart slowly found his way back—he married in 2000, and in late 2001 contacted Lee and Lifeson about working on some new music together—and Rush was back in the game.

Their lead singer didn't understand their lyrics

As noted by The Chicago Tribune, Neil Peart's song lyrics were unique in the world of rock. Instead of writing about the usual subjects for rock songs—love, partying, how cool it is to be a rock star—Peart wrote about existential subjects, philosophical dilemmas, and science fiction concepts. As noted by SPIN, Peart was a voracious reader who devoured books whose ideas then found their way into his songs—but he was also inspired by his own experiences, such as his frequent motorcycle trips.

The result of those influences were lyrics that are often difficult to parse—so difficult, in fact, that The Guardian reports lead singer Geddy Lee was often at a loss as to their meaning, admitting that he can "barely" make sense of them. That's not too surprising when you consider that Rush's breakthrough 1976 album, "2112," is a concept album about a future where everyone lives in the Solar Federation, a group called the Temples of Syrinx control every aspect of life, and a lone hero fights to express his individuality through playing guitar.

To Lee, though, that doesn't matter—and he has a point, arguing that the words and music combine to create a "picture of a meaning." In other words, we all interpret art in our own way.

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ignored them

Rock and roll has a certain image. Your cliché rock star is elegantly wasted, wild, and weird. There might be hotel room trashing, or backstage bacchanalias, or stints in rehab—all acceptable as long as there's great music, too. But Rush never fit that mold. As noted by Sharp Magazine, Rush has always been a nerd's band, geekily pursuing progressive rock instead of rock star glamour. The complexity of their musical arrangements combined with the intellectual pitch of Neil Peart's lyrics have doomed any effort to peg Rush as a "cool" band.

And that image has cost them certain perks of fame. As reported by Nola.com, despite selling millions of albums and selling out countless stadiums on tour, Rush didn't appear on the cover of Rolling Stone—a milestone for any rock band—until 2015, 41 years after their debut. Rolling Stone's publisher, the legendary Jann Wenner, is reportedly not a fan of progressive rock in general and Rush specifically—which also explains why Rush wasn't inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (which Wenner co-founded) until 2013.

According to Rolling Stone, though, guitarist Alex Lifeson got his revenge: His speech at the induction ceremony consisted of one repeated phrase: "Blah, blah, blah."

Rush called it quits when Neil Peart couldn't keep up

Rush was an unusual band in many ways, but one way that set it apart was the unusual tightness and necessity of its members. Where many rock bands can replace musicians—even lead singers—and carry on, Rush would simply no longer be Rush with Alex Lifeson's signature guitar work, Geddy Lee's nimble bass playing and iconic voice, and Neil Peart's intricate drumming and dense lyrics.

Peart held himself to the highest standards of drumming, and his live performances were a physical workout. He once told Rolling Stone he had difficulty playing older Rush songs because he'd become such a better drummer over the years. When the band announced their retirement in 2015, one of the core reasons was Peart's increasing struggle to maintain his own standards. As reported by Louder, Peart—by then in his 60s—suffered a range of maladies including chronic tendonitis which made it incredibly painful for him to pound the skins for hours every night on tour. Unwilling to perform at anything less than his best, Peart chose to retire from touring. Lee and Lifeson opted to end the band instead of trying to replace a drumming legend and old friend—though they held out the possibility of working together on other projects, such as film soundtracks.

Sadly, Peart was diagnosed with brain cancer a few years after his retirement, and as reported by the CBC he passed away in 2020.

There won't be any post-retirement releases

When some hugely successful bands retire or otherwise end their recording careers, fans can hope for some bonus albums as unreleased material is culled from the archives. That's because most bands record a lot more songs than they officially release, so once they call it quits they can go back and finally give those rejected songs a chance.

That won't be the case with Rush. Despite a recording career that lasted 19 albums and 39 years, according to Rolling Stone there simply aren't any left over songs. Guitarist Alex Lifeson says that the band rejected the idea that you record 20 songs and then pick the 12 "best," because that implies you wasted your time recording the other eight songs. Instead, Rush planned their albums carefully and only worked on songs that they knew were good enough to release. They knew whether an album was going to be 8 or 10 songs before they even stepped inside the studio.

Bassist Geddy Lee echoes the sentiment, saying that the band always used the material they wrote—if they didn't like a song, they stopped writing it. Interestingly, Lee is quoted by Ultimate Classic Rock as saying "there are really no unreleased Rush songs that were worth a damn," which implies there might be some unreleased songs that are simply trash. We may never know for sure.