What Dragons Look Like Around The World

If you were asked to identify the first fantasy monster that came into your head, there would be more than a fire-breathing chance that you would shout out "dragons." From Daenerys' three dragons in "Game of Thrones" to J.R.R. Tolkien's Smaug to Puff the Magic Dragon, dragon lore is wildly popular today. But in traditional culture, the dragon had a much deeper resonance. It represented primal forces of creation, destruction, and death. The dragon has figured in human folklore and mythology since its earliest days all around the world. It is truly remarkable that all around the world, almost every tradition has created some sort of dragon mythos to represent primal forces. If dragons were classified scientifically, there would be two main branches of the dragon family, one originating in East Asia, and the other originating in the Middle East and Europe. Then there are similar serpentine monsters in other traditions around the world.

Dragons, as described by Britannica, come from the Greek word "drakōn," a term used to describe any large serpent. Dragons, therefore, are essentially serpents or snakes, though imbued with power. As the dragon mythos developed, the physical shape of the creatures evolved, with some types of dragons co-opting a hodgepodge of other animal characteristics. Because of this, folklore around the world has different versions, or species, of dragons. Let's take a look at what some of the more prominent dragons around the world look like.

There are at many varieties of dragons in Chinese lore

In Eastern Asia, specifically China and the lands about it, dragons were called by the general name Long. Chinese dragons were magnanimous creatures, holding a place of esteem in mythology. "The Chinese Dragon" details how there are several varieties of these dragons broadly divided into dragons of the sea, sky, and marshes. The most well-known in Chinese folklore is the Shen Long, which operates in all three regions.

According to the World History Encyclopedia, Chinese dragons figure prominently as symbols of power and royalty and often incorporated the parts of other animals. A typical description included deer antlers, demon eyes, carp scales, eagle claws, and a snake neck. Other descriptions of the Chinese dragon claim that it could change its appearance at will. Some Chinese dragons had wings, but most did not — although almost all could fly. "The Chinese Dragon" notes that dragons may be either red, black, red, yellow, or white. These colors, according to "The Mythical Creatures Bible," are symbolic, indicating a cardinal direction and an augury such as the coming of spring or impending famine.

Different dynasties adopted different-colored dragons as their mascots. For example, the Qin dynasty's imperial color was yellow, so it adopted yellow dragons as its "official dragon." For the Ming, it was red. Also, Chinese dragons could have three, four, or five claws. Four was the most common version, and five-clawed dragons were held to be associated with the imperial family.

Japanese dragons could be many-headed and liked to get drunk

Japanese dragons fall firmly into the tradition of Chinese dragons, albeit with their own unique characteristics. As described by "The Mythical Creatures Bible," the Japanese dragon, called Ryu, is antlered and usually possesses three claws, although there are some depictions which give these creatures up to five. "All About Chinese Dragons" further describes the Japanese dragons as more slender than Chinese dragons and more land-based.

Imperial tradition in Japan, like other Asian royal traditions, ties dragon ancestry as a part of royal lineage. However, Japanese dragons depart from typical munificent Asian dragons in that some are evil. One, Yamata-no-Orochi, sported eight heads, eight tails, and eight claws per foot. This evil dragon devoured seven sisters but was finally dispatched by the storm god Susanuo, who got the beast drunk and chopped off each head as it dunked it into a barrel of sake. According to the Japan Encyclopedia, after dispatching the monster, the god discovered the magic sword Kusanagi no Tsurugi, which would become a part of Imperial Japan's regalia.

The Vietnamese dragon is a symbol of royalty

In the folklore of Vietnam, the dragon is perhaps the most sacred creature. As explained by the British Library, dragons are tied very closely to the beginnings of the country, since a dragon is considered one of the progenitors of ancient Vietnamese royalty and in fact the Vietnamese people. According to legend, the water dragon Lac Long Quan married a fairy in bird form named Au Co, who laid 100 eggs from whence the people of Vietnam came. In fact, Vietnamese people are said to be themselves "con rông cháu tiên," which means "children of the dragon and grandchildren of the fairy."

In style, Vietnamese dragons are very similar to Chinese dragons. However, there are some differences. According to "The Mythical Creatures Bible," Vietnamese dragons' serpentine bodies are divided into 12 sections which represent the 12 months of the year. The British Library notes that like in China, the number of claws a dragon had indicated what level in the social hierarchy that dragon belonged to. A five-clawed dragon, for example, indicated royalty, while a three-clawed version was associated with commoners. The winding form of the dragon is also associated with Vietnam's own geography, with the northern section being the tail of the dragon, the middle the mountains, and the head its most southern part.

In Hinduism and Buddhism, the Naga is a half-serpent, half-human deity

The Hindu and Buddhist naga is a creature that is often classified alongside dragons or at least as a very close cousin to them. According to Britannica, the name "naga" is the Sanskrit word for "serpent." Nagas were said to be half-human and half-cobra. Naga were sent to a bejeweled underworld kingdom called Naga-loka by Brahma when they became too numerous on Earth. Their function was to bite those who were to prematurely die or those that were evil.

"The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols" describes how in Buddhist mythology, Naga were also capable of full human form and most closely associated with aquatic realms as well as being the guardians of fabulous treasures. The nagas were also divided into five castes which corresponded to the castes of traditional Hinduism. Typically, nagas were depicted as having serpentine bodies but with a human upper body. Almost always, they were white in coloration, with their hands in supplication or offering jewels. About the Naga's head there was almost always a cobra hood.

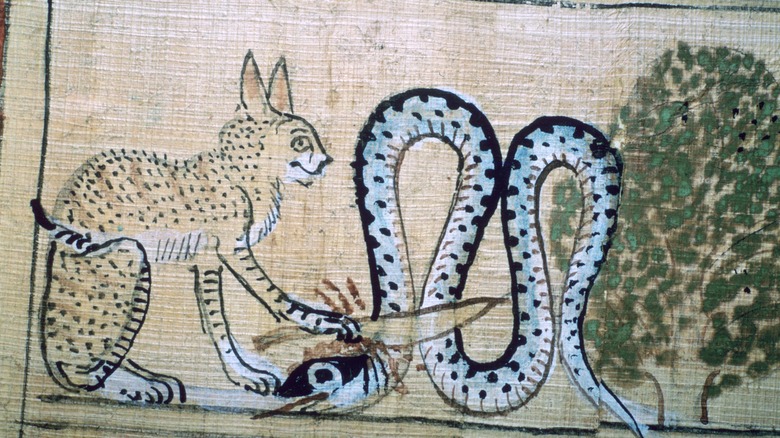

In ancient Egypt, the god of chaos took the form of a dragon

Ancient Egypt had many deities, and the ancient Egyptians were among the first to conjure one of the earliest forms of dragons. The sun god Re (or Ra), as told by Britannica, was a divine creator. Part of the mythology surrounding Re was that after he finished a day's journey in his solar ship, he needed to vanquish a demon dragon so that day could come again. The demon Apopis (aka Apep, Apophis) was one of the earliest incarnations of a dragon image. Serpentine, he was an agent of chaos that threatened the destruction of the world. Invariably, Apopis is depicted as a coiled snake.

According to the World History Encyclopedia, Re often dismembers the demon into 12 pieces, allowing life to continue. Other works show the snake demon destroyed by spells and incantations from other creatures. Invariably, however, the serpent is reborn in order to try to bring about the destruction of the world again in an endless cycle. One can clearly see a link between the destructive evil of Apopis and the best-known depictions of the malicious and avaricious dragons in the European tradition.

The ancient Greeks and Romans fought dragons with heroes and gods

In the classical West, the Greeks and Romans depicted dragons through a variety of mythological monsters, each with variations. Their versions were spawned out of the more evil dragon myths of the ancient the Middle East. One of the most famous tales is that of the Hydra. This monster, according to Britannica, was a water snake creature with about nine heads.

The Hydra's most famous characteristic was that each time a head was cut off, two more would appear. As described by Tufts University's Perseus Project, the monster terrorized the swamps of a region called Lerna when the hero Heracles (aka Hercules) was tasked to kill it as part of his famous Twelve Labors. To slay the monster, Heracles first lured it out of its den by shooting flaming arrows. Then Heracles grappled with it. Every time the hero destroyed a head, his companion Iolaus cauterized the monster's neck so new heads would not grow. After Heracles cut off the final head, which was immortal, he buried it on the side of the road and covered it with a big rock.

Another destructive dragon from classical mythology is the Python. Python, naturally enough, was a humongous snake which, as described by Britannica, had angered the god Apollo either because it wanted to give its own oracles or attacked Apollo's mother Leto while she was pregnant with the god. Either way, Apollo killed it while still a babe.

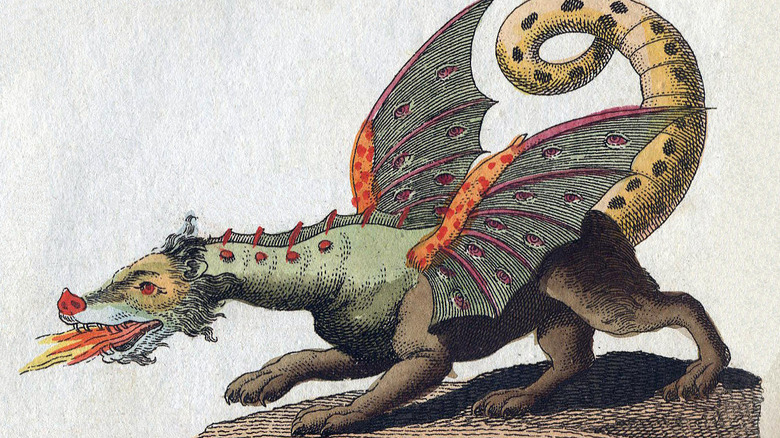

Western dragons are fire-breathing treasure hoarders

Perhaps the most well-known depiction of dragons is the Western, or Occidental, dragon, which developed out of ancient folklore in the Middle East and Europe. There are many different varieties of these dragons. According to "Giants, Monsters, and Dragons," your garden-variety western dragon is large, scaled, and crocodilian, with lizard-like clawed feet. Some of these types of dragons may have a dorsal ridge that extends down to a long tail, which may or may not be barbed. Of course, these dragons breathe fire or various deadly fumes. The color of the Occidental Dragon is usually either green, red, or black. Rarer are blue, yellow, or white varieties. Some are depicted with wings, others not.

By the time of the Middle Ages, Occidental dragons were painted as invariably evil, being an emblem of greed with their guarding of treasure hoards. The malice of the Occidental dragon may be said to be the work of Christianity, which fully demonized any positive traits that may have been associated with this symbol of pagan polytheism. One of the most famous historical depictions of this type of dragon is the one which was slain by St. George of England.

The Occidental dragon is most famous in literature, particularly high fantasy. From Smaug in J.R.R. Tolkien's "The Hobbit" to the dragons of Westeros in George R.R. Martin's "A Song of Fire and Ice," Occidental dragons have filled the public's imagination with their power and ferocity.

The wyvern is a two legged, flying dragon

The wyvern, or guivre in French, is a variation of the Western dragon which makes one of its earliest appearances on the Bayeux Tapestry, representing the Anglo-Saxons during William the Conqueror's conquest of England. In fact, it is thought that this early appearance of the wyvern may have inspired the famous Red Dragon of the Welsh flag. Research by William Sayers shows that the wyvern had a mixed origin among Saxon, Germanic, and Norman peoples, although the creature itself had a slow evolution from that of just an ordinary evil poisonous snake to that of a hybrid fantastical beast.

As analyzed in "Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art," the wyvern is a flying serpent with the body and head of a traditional dragon but with the legs of a raptor such as an eagle. Its tail is barbed. They are somewhat like the dragons of the "Game of Thrones" universe in this respect. Wyverns are common in heraldry and supposedly represent tyranny and pestilence, as well as conquest of a vicious enemy. Sometimes, wyverns are depicted without their bat-like wings, which reclassifies them into the subspecies lindworms.

Russian dragons are like Western dragons, but with more heads

The dragon of Eastern Europe was very similar to that of Western Europe. In fact, the Slavic dragon may be, in some ways, like the Wyvern, to be just a variation of the Western dragon. As detailed in the "Encyclopedia of Russian and Slavic Myth and Legend," they are serpentine, but unlike Western dragons, Slavic dragons may have multiple heads, ranging from three up to twelve. Other variations depict dragons as having the head of a serpent and the body of a man which flew on a winged horse. "Giants, Monsters, and Dragons" goes further to state that other dragons had the head of a man and the body of a serpent. So these types of dragons could be all over the place.

Slavic dragons are also credited with immense powers, such as being the cause of solar and lunar eclipses. Like the Western dragon, Slavic dragons have no redeeming qualities, being an embodiment of evil. As a result, these dragons, also known as zmei, are the subject of many spellbinding tales of Russian folklore. Perhaps the most famous tale is that of Dobrynya Nikitich, who slew the three-headed dragon, Zmey Goryshche. Nikitich had slain the dragon's offspring, so the creature naturally wanted revenge. Still, the dragon ended up getting slain in the end.

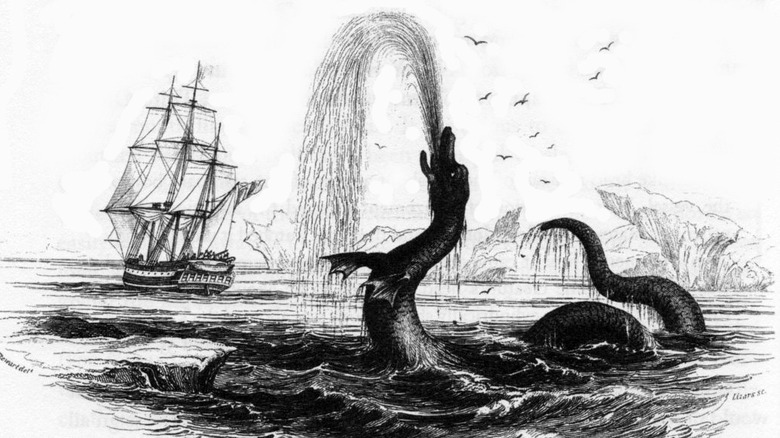

The seas also hold many forms of dragons

Sea serpents are, in shape, form, and essence, aquatic dragons. Most cultural traditions that are close to the sea have some lore concerning these monsters. According to Britannica, ancient Middle Eastern and Hebrew lore speaks of how a god or gods had to defeat a dragon-like creature in creation. In Hebrew tradition, it is Leviathan, usually described as a monstrous sea serpent or dragon. In Mesopotamia, the sea goddess Tiamat was subdued by the god Marduk and used to create the world. In both cases, these myths are obvious allegories of the struggle between order and chaos.

There are some very fringe notions that sea serpents might actually exist. This is mainly due to the fact that it is much easier to confuse a pod of dolphins and its undulating movements with that of a huge serpent. Also, when considering that there are already monstrous things in the ocean such as giant squid, it is easy to see how they can be easily confused with krakens.

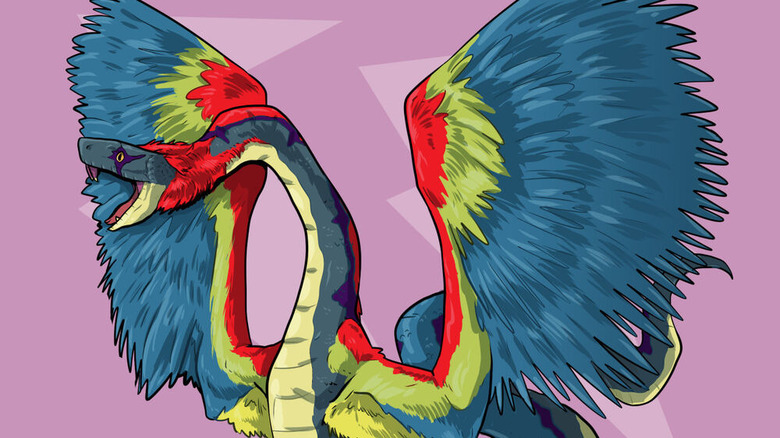

Quetzalcóatl was the winged serpent of ancient Mexico

Dragon folklore wasn't limited to the people of Europe and Asia. In the Americas, indigenous people also had their own dragons. Perhaps the most famous of these is Quetzalcóatl, one of the chief gods of ancient Mesoamerica. According to the World History Encyclopedia, Quetzalcóatl literally means "Plumed Serpent." These types of feathered serpent gods were worshipped throughout Mesoamerican history. Quetzalcóatl was a wind and rain god and responsible for the creation of the Earth and humans. He was a giver of technology and agriculture to humanity. Because of this, Quetzalcóatl is much more comparable to Eastern dragons than those of the Western tradition.

So what did Quetzalcóatl look like? The god was depicted in art as having a rattlesnake's body, but with a beak and a feathered crest. Some ancient representations show black and yellow feathers as well as having jewelry such as jade earrings. Quetzalcóatl today is still seen as a totem of indigenous pride within modern Mexico and Central America.

The peuchen of Chile is a shape-shifting vampire

Contrasting with the feathered serpent of ancient Mexico is the peuchen of southern Chile. Here, folklore takes a dark turn to combine the dragon with everybody's favorite monster: the vampire. According to the "Encyclopedia of Beasts and Monsters in Myth, Legend and Folklore," these evil creatures figure strongly in the mythology of the Mapuche and Chilote people.

The monsters had one thing on their mind: sucking the blood of animals and humans. To gain their sustenance, they had the magic ability to assume any shape, but they most commonly took the form of a giant snake with enormous wings. The monster also had a hypnotic stare which immobilized its victims. It also, as described by "Fantastic Fearsome Beasts," made a peculiar hissing sound that was synonymous with death. According to folklore, only medicine women have the power to destroy these monsters. It is believed that the peuchen may have eventually morphed into the chupacabra.