What It Was Like Traveling On The Hindenburg

What if you could travel back in time to take a ride on the rigid airship the Hindenburg? Would you jump at the thought of riding one of the most luxurious forms of transportation in the 1930s? Or would you pass in a heartbeat, unsettling footage of the fiery inferno hardwired into your brain? While most of us think of zeppelins as among the sketchiest and most dangerous forms of transportation, they used to have a different reputation.

And while the sight of the Hindenburg flying over the United States with a swastika also appears horrifying by today's standards, things were ... well, a little different back in the 1930s. People didn't have the luxury of hindsight as we do today. After all, zeppelins hadn't started bursting into flames mid-flight yet, and Adolf Hitler and his Nazi cronies didn't have the blood of millions on their hands.

Sure, it's a stretch of the imagination, but back in the 1930s, travel by zeppelin represented a luxurious and expensive way to voyage between the States and Europe, right up there with the Titanic of a couple decades earlier. What was the Hindenburg like on the inside? And why did so many people fork out the big bucks for a ride? Here's what it was like traveling on this one-of-a-kind airship.

Zeppelins revolutionized transatlantic travel

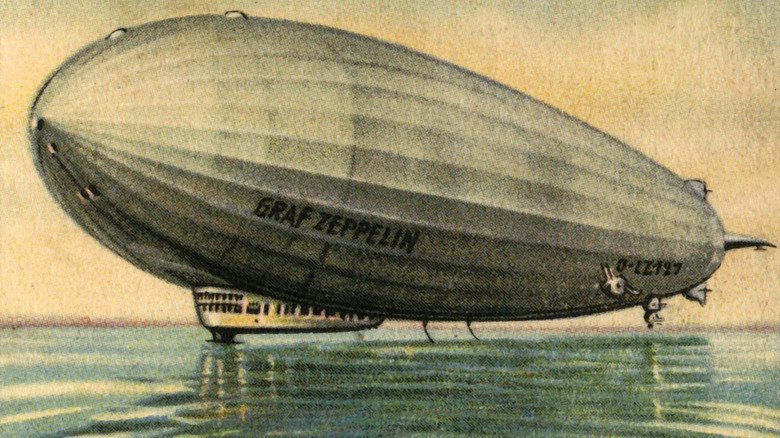

It's easy to forget that the only commercial way to cross the sea in the 1920s was by ship. But everything changed with the first rigid airship passenger flight across the Atlantic in 1928, the Graf Zeppelin (via Core77).

The Graf Zeppelin was the largest airship of its day, and it proved instrumental in launching the first commercial transatlantic air service. Where did the Graf Zeppelin fly? It traveled round-trip between Brazil and Germany, providing an increasingly popular service. During its air career, it flew more than 1 million miles over the course of nearly 600 flights, per Airships.net. What's more, the Graf Zeppelin carried "thousands of passengers and hundreds of thousands of pounds of freight and mail, with safety and speed." Ultimately, the Graf Zeppelin paved the way for a more ambitious rigid airship, the Hindenburg.

Like the Graf Zeppelin, the Hindenburg made regular flights between Germany, North America, and Brazil, according to Airships.net. But it proved even more luxurious and bigger than the Graf Zeppelin, and it set a new standard for transatlantic air travel as the world's largest airship. An emphasis on luxury proved essential to restoring the image of the zeppelin. You see, even though the Hindenburg disaster was many years in the future, airships had a troubled history for other reasons.

Airships had a complex history

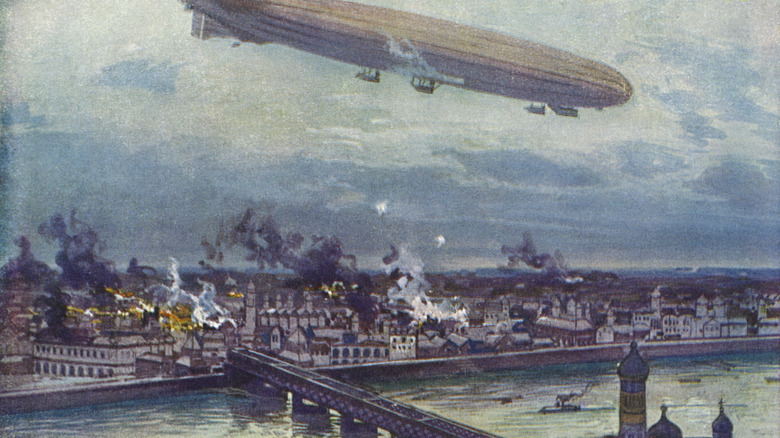

Even though airships didn't yet have their reputations sullied by the Hindenburg disaster, they still came with a complicated history. They might have been a downright spooky sight for some World War I veterans. Why? They were used extensively as scouts and bombers by the German war machine during the Great War. All told, historians attribute the deaths of 500 people to zeppelin bombing raids over Great Britain.

According to Kate Argyle of English Heritage in an interview with the BBC, the use of zeppelins ultimately came with "no military advantage. It was all about instilling terror and really that's what these aerial bombardments did." The zeppelin's weaponization came with a strong stigma that made the airships a hard sell as commercial air travel (via Wired).

With the surrender of Germany at the end of WWI in 1918, the Treaty of Versailles prohibited the Germans from building any zeppelins (via History) until 1926, the same year work began on the Graf Zeppelin. It was christened on July 8, 1928, per Airships.net. By 1929, the Graf Zeppelin became the first airship to make a passenger-carrying flight around the world. Most importantly, the Graf Zeppelin made incredible strides when it came to recouping the image of the airship after the Great War. Now, zeppelins were in, and the Hindenburg would continue the PR campaign.

The fastest way to travel the Atlantic

Besides being larger and more lavish than the Graf Zeppelin, the LZ-129 Hindenburg offered the first consistently scheduled commercial passenger service between the United States and Europe, according to Airships.net. The Hindenburg also represented the fastest way to get across the Atlantic Ocean, transporting passengers from Frankfurt, Germany, to Lakehurst, New Jersey, in just a few days.

The Hindenburg enjoyed a maximum speed of 84 miles per hour, according to Airships.net, and it cruised at 76 miles per hour. How about its cruising altitudes? The giant dirigible enjoyed a standard cruising altitude of 650 feet, which many passengers found pleasant for a transatlantic journey. That said, the Hindenburg would go down to as low as 330 feet, as reported by Airships.net. This would provide passengers with incredible views of the landscapes below.

But there proved a more critical reason dirigible pilots wished to stay out of the clouds: to avoid thunderstorms. The last thing rigid airships such as the Hindenburg wanted was to fly in electrically charged air. Moreover, sailing too high necessitated "valving hydrogen" from the top of the dirigible, which always presented a fire hazard. Flying at such low altitudes meant passenger compartments weren't pressurized (except for the smoking room). Core77 notes that passengers could even open the Hindenburg's windows to get a little fresh air.

Passengers paid through the nose to travel on the Hindenburg

People paid a high price to enjoy airship travel. The Hindenburg could hold a total of 50 passengers (later that would increase to 72), and the crew included between 40 and 60 individuals. According to Smithsonian Magazine, one ticket survived the Hindenburg disaster: Burtis J. "Bert" Dolan paid 1,000 German Marks (RM) for a ride on the state-of-the-art airship.

What was 1,000 RM in U.S. dollars? During the Great Depression, it proved the equivalent of $450 per passenger. Factoring in inflation as of 2021, that's $8,372 per passenger, according to the Dollar Times! How did these prices compare to the ocean liners of the day? The Travel reports first-class passenger ticket prices of between $157 and $240 for German ocean liners. In other words, Dolan paid nearly twice as much money to take a zeppelin over a ship.

Remarkably, Dolan's ticket and passport survived the midair fire largely unscathed. But Dolan didn't prove so lucky. Nelson Morris, Dolan's friend and fellow passenger, last saw Dolan before jumping from the zeppelin's window. Dolan was right behind him, but those few precious seconds meant the difference between life and death. The retrieved passport and ticket would later help first responders identify Dolan's body. And the elegant ticket printed in German with an electric blue border remains the last witness to the height of airship travel.

The Hindenburg's many amenities

Before delving more deeply into the Hindenburg disaster, let's take a closer look at what passengers received for shelling out thousands of marks. By nixing the need to sail the ocean blue, passengers avoided getting seasick. Since anti-nausea meds like Dimenhydrinate (better known as Dramamine) wouldn't enter medical use until 1949 (via Britannica), zeppelin travel marked a welcome relief for those prone to upset stomachs.

But the wonder of airships didn't end there. NPR reports that the Hindenburg's speed far outstripped the best cruise liners of the time. It could cross the Atlantic in half the time of the Queen Mary, for example. Takeoffs and air travel also proved gentle and bump-free. Some passengers would later recall barely noticing when airships floated up into the sky at a trip's start. And once in flight, Core77 reports that dirigibles proved so steady "you could balance a pencil on a table."

A spacious layout encouraging movement and entertainment

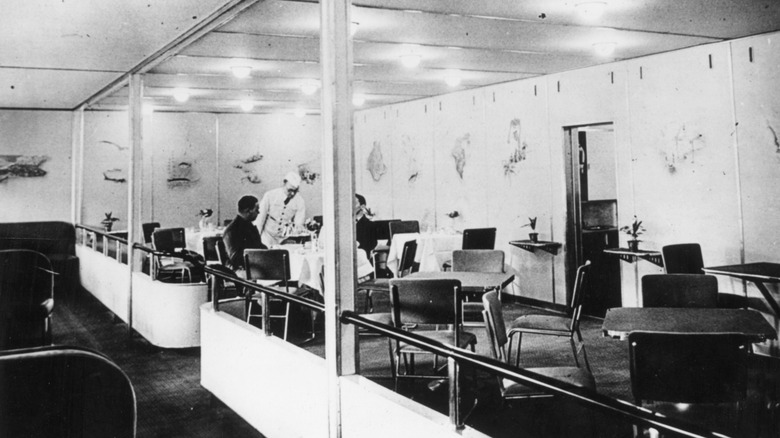

What did the interior structure of the Hindenburg look like? According to Airships.net, the space could be organized into three principal categories: crew areas, the control car, and the passenger decks. Passenger rooms covered two expansive decks labeled A and B.

What could you find on the A level? Everything from a writing room and a lounge to a dining room. Passengers also enjoyed frequenting the starboard and port side promenades, where they could marvel at the world below. Besides these communal spaces, the A deck housed 25 centrally located double-berth cabins.

How did the B deck (which was below A) compare? It proved more functional, containing shower and bathroom facilities (but it did have a bar). It also housed crew spaces like the officers' mess, the kitchen, and a cabin for the chief steward. In the case of the Hindenburg, the chief steward was Heinrich Kubis, the world's first air attendant, as reported by Aerotime Hub. Kubis' room contained the only link between crew spaces and passenger areas (via Airships.net).

Interior décor of the Hindenburg

Apart from the airship's layout, what did the interior décor look like? The dining room measured 13 feet wide by 47 feet long and took up the full port side length of A deck. Contemporary photos show a cheery room accented with red carpet and upholstery and featuring plenty of ceiling lights and illumination from the Hindenburg's downward-facing, diagonally slanted windows.

By today's standards, the dining space might feel oddly reminiscent of an office cubicle. But the ship's creators attempted to liven up the stark minimalism with hand-painted silk wallpaper. According to Airships.net, the wallpaper featured designs by Professor Otto Arpke which were inspired by Graf Zeppelin's trips to South America.

Other noteworthy rooms included the small writing room, which contained more exotic scenes painted by Arpke. The 34-foot-long lounge featured another Arpke masterpiece, a pastel-hued world map depicting the first maritime voyages of discovery that knit the Old and New Worlds together as well as notable flights of past zeppelins.

Cabins and sleeping arrangements

Perhaps the least luxurious aspect of flying on the Hindenburg would have been the cabins where guests slept (via Core77). According to Airships.net, they proved small and highly functional, not unlike a train or ship's sleeper compartment. That said, passengers did enjoy hot and cold running water, although you had to head to B deck to use the facilities or take a shower.

Thin sheets of fabric-covered foam lined cabin the walls, and each unit measured roughly 78 inches by 66 inches. Passengers enjoyed one of three color schemes: beige, gray, or blue. Cabins contained two bunk-style beds. The lower one remained fixed in place, but passengers could fold up the upper bed to get it out of their way. Passengers also enjoyed access to a small curtain-covered closet and a button to call the flight attendant.

More cabins would get added to the Hindenburg when it wintered over in Frankfurt from 1936 to 1937. These cabins proved a bit larger than previous ones located on A deck, and they featured windows affording outside views. Although these additions increased the overall weight of the airship, this no longer proved a significant concern by 1937. Why? Because instead of relying on helium to make the ship airborne (as it was designed to do), the airship's owners had settled for hydrogen, which has superior lifting power (via AAPT Physics Education). The switch occurred to due U.S. restrictions on exporting helium, per USA Today.

Clever design and safety features

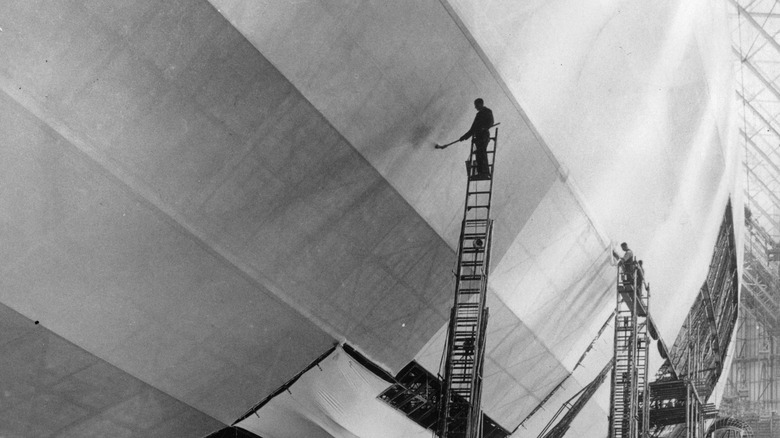

What else might you have noticed about the Hindenburg's interior? As reported by Airships.net, it had many innovative design features meant to reduce the overall weight of the airship. Even the ladders used to access upper beds in the cabins had perforated holes to minimize bulk. Chairs also proved exceedingly well-thought-out, crafted from a tubular aluminum design.

The lounge even contained a duraluminum baby grand piano camouflaged in yellow pigskin. According to NPR, one of the strangest accommodations remained the one napkin provided in an envelope to each passenger for the duration of the trip. Some passengers found the necessity of using one napkin the entire trip as odd, but it helped cut down on the airship's overall weight. Why were these innovations so important? According to Core77, it permitted the crew to haul more cargo in the interior of the airship. This included everything from luggage and mail to automobiles. What else impacted the design of the Hindenburg's interior? Fire safety concerns.

Because zeppelins like the Hindenburg represented tinderboxes due to the highly flammable hydrogen gas used to inflate them, engineers took flame hazards very seriously (per Airships.net). Yet, surprisingly, the Hindenburg included a smoking room, pressurized to ensure that the hydrogen on the rigid airship didn't ignite.

The Hindenburg's food was over-the-top

The Hindenburg boasted high-end dining experiences with fancy place settings and fine china. It offered guests some of the most delectable food on the planet, from caviar to fattened ducklings (via Atlas Obscura). Consider this, the Hindenburg's final flight featured Paris' own Xaver Maier of the Ritz.

And if overindulging in food wasn't enough for passengers, they could also drink themselves silly with a wide range of cocktails. To prove this point, the Hindenburg even included hangover cures for the morning after. These cures included a whole raw egg with hot sauce and oysters.

Best of all, because zeppelins flew at low altitudes, passengers thoroughly savored the cuisine served to them. As NBC News reports, a combination of high altitude and dry air deadens airline passengers' taste buds today, hence the blandness associated with airplane food. But you would have retained fully functioning taste buds on the Hindenburg. Of course, not all passengers on the Hindenburg ultimately enjoyed the food. Many American passengers reported the cuisine as too creamy and rich for their tastes (via NPR).

A survivor recalls the Hindenburg disaster

When you watch the footage of the Hindenburg disaster, it's unfathomable to think that anybody survived. However, as reported by Smithsonian Magazine, of the 97 passengers and crew members on board that day, 62 lived.

According to the Associated Press, Werner Doehner was just eight years old at the time, and as he recalled in 2017, "Suddenly the air was on fire." His mother threw him out the window to the ground below. In the resulting chaos, Doehner, his brother, and his mother all managed to escape, but Doehner's father and sister both died in the fire. Doehner would spend three months in a New York City hospital recovering from the burns he received to his face, legs, and hands, which required skin grafts.

Today, scientists and researchers continue to debate what ultimately caused the Hindenburg to burst into flames and crash (via Smithsonian Magazine). Most scientists agree that highly flammable hydrogen, mixing with oxygen, provided the perfect "gasoline" for the fire. But they've come to slightly different conclusions about what caused the spark that devoured the dirigible in 34 seconds. One of the most outspoken researchers is Addison Bain, a NASA rocket fuel expert. According to Florida Today, Bain hypothesizes the zeppelin's butyl-based paint coating may have failed to dissipate the buildup of electrical charges outside of the airship. The result? A monster-sized accumulation of deadly static electricity that ignited the cover and then the hydrogen inside.

The end of rigid airship travel

Although researchers may continue to disagree about what caused the Hindenburg to go up in flames (via Florida Today), they can't argue about the impacts of the fire on the rigid airship industry. The Hindenburg brought the age of elegant airship travel to an abrupt halt. After the disaster, the Zeppelin Company promised never to use rigid airships filled with hydrogen gas. But due to the restriction of helium exports from the U.S. (via Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences), they remained stuck between a rock and a hard spot.

People were terrified of flying on hydrogen-floated devices. According to History, they also became disillusioned by the Nazis with the invasion of Poland in 1939, ushering in World War II. From that point on, it's safe to say fewer and fewer people wanted to float around on swastika-marked dirigibles.

As stated by Live Science, "the Hindenburg was supposed to be ushering in a new age of airship travel. But the crash instead brought the age to an abrupt end, making way for the age of passenger airplanes." As for the use of zeppelins for military purposes? During WWII, the U.S. relied on airships for search and rescue, minesweeping, and surveillance, but Americans proved the only power to use them, per Centennial of Flight.