The Legend Of Ogres Explained

Ogres have been stomping their way through folklore and fairy tales for a long time, and they've even made the jump into more modern culture. There is, of course, Shrek and the approximately 27 sequels. Ogres have also moved on to take their place in games like Dungeons & Dragons and pretty much every fantasy game that's ever been made. Bottom line: Ogres have done pretty well for themselves.

Perhaps not surprisingly, ogres weren't always big green goofballs, or the wives of green goofballs. The actual folklore and mythology of them goes back a long way, and weirdly, people were talking about them long before they were even calling them "ogres." They pop up in stories from all around the world, and they're not always big, scary, heartless creatures just on the lookout for their next meal.

They're kind of like people: Sometimes they're better, sometimes they're much, much worse.

What does it mean to be an ogre?

Folklore has been filled with ogre-like figures for a long time, and Oxford Reference says there's a few different explanations for where the word "ogre" comes from.

One is that it's derived from the name of one of mythology's gods of the underworld, Orcus. But, shouldn't that be "orc?" There are plenty of orcs in folklore (and gaming) too, and if that seems confusing, there's a good reason for it. According to the "Companion to Literary Myths, Heroes, and Archetypes," the term goes back even farther, and it's rooted in words like "huerco," which is an old Spanish word for devil.

By the Middle Ages, Arthurian poet Chretien de Troyes was using it, but not in the same way it's used today. His ogres were, ironically, those who lived in Logres, the spiritual center of King Arthur's entire domain (via USC). When Lancelot finds out many of these people are being held prisoner in the underworld, he heads down there (in a British version of the Orpheus myth) to save them. From then on, "ogres" are connected with being condemned to hell, and it seems that's where they become associated with the demonic, the infernal, and the ever-hungry in a pop culture kind of way. Isn't mythology fun?

Who is this Orcus guy?

Most sources — including the "Companion to Literary Myths, Heroes, and Archetypes" — agree that ogres got most of their now-familiar traits when they became linked with the god Orcus. He was basically the Roman equivalent of Hades, says Britannica, and ruled the underworld as the consort to the goddess of death.

Orcus is sometimes depicted as a massive head with a wide, gaping mouth — the better to swallow the sinners with. And that's actually important: Ogres would become known as creatures driven by their hunger, after all. It's believed that idea harkens back to some of the very earliest Greek and Roman myths of figures like Cronus/Saturn, who famously ate his children in a failed attempt to keep them from rebelling against and ultimately killing him. (Spoiler alert: It didn't work.)

By the time the tales reached the Celtic world, Orcus became known as the polar opposite of a figure called Gargan-Gargantua. Where he — the Celtic sun — gave life, Orcus was waiting to take it away by devouring souls and condemning them to the land of death, darkness, and shadows. That image ultimately shaped the ogres that became the bane of fairy tale princesses and folklore's children.

There's a wide variety of ogres

These monsters are often thought to look like a kind of human giant, but according to "Folktales and Fairy Tales: Traditions and Texts from around the World," that's not always the case. While the motivations of an ogre are typically similar no matter where the story comes from — they're looking for food — these giants can have a wide range of traits.

In Chinese tales, for example, ogres are giants with blue skin, while in Western Asia, they have black skin. And in some African tales, they're white-skinned. Sometimes, they're incredibly clever, and sometimes, they're ridiculously stupid. And sometimes, they look downright horrific, with a tooth-filled mouth that literally stretches from ear-to-ear, and arms they can extend to reach as far as they want, sort of like a really awful version of Reed Richards.

They've even sort of evolved for hunting humans, sporting an overdeveloped sense of smell that they can use to hunt their prey with. Ogres tend to be ridiculously strong, stir up windstorms when they walk, and let their fingernails grow so long they're officially in the "uncomfortable" territory — the longer they are, apparently, the better they are for catching humans.

As if that's not disturbing enough, there's also a tradition of undead ogres with bodies that are starting to decay. Sweet dreams!

They're driven by their desire to eat people — particularly children

Whenever ogres show up in stories, they're usually being driven by a relentless need to devour human flesh. (Think Shrek is the exception? There's a fan theory that says Fiona was eating the fleshy remains of the knights who were trying to save her, and it's not far-fetched.)

There's more to this than just the scare factor, though, and according to the "Companion to Literary Myths, Heroes, and Archetypes," their preference for eating children is a reflection of a belief held by many ogres, specifically, that eating the young will grant them eternal youth.

There's another layer of meaning here, too. By making children the victims, later stories — like Jacques Chessex's L'Ogre — make ogres symbolic of the overbearing, demanding father figure who doesn't literally eat his children but crushes them with his discipline, scorn, and disapproval.

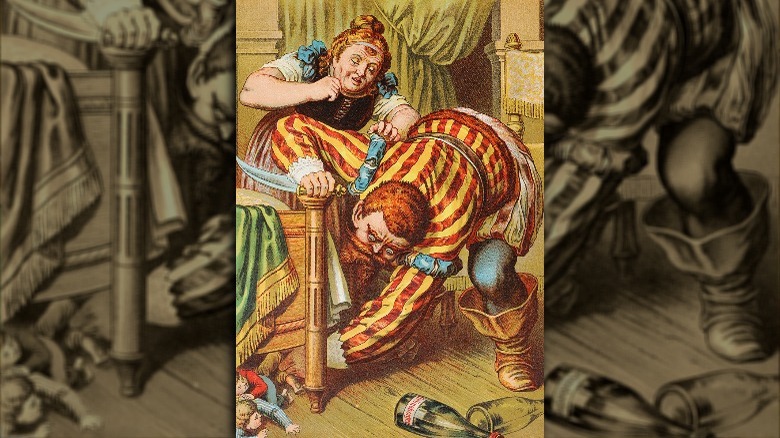

A Female ogre is called an ogress, and there's enough tales about them to see how their cannibalism can be used as a metaphor for human mothers who are over possessive and jealous. There's another weird connection here, and that's the one between cannibalism and a refusal to marry or bear children. Folklorists say that when cannibalism shows up in some folk stories, it's a cautionary tale — but not the one some might expect. Much like seeing one's children being cannibalized by an ogre means the end of a family line, so does a child's refusal to marry or have children of their own.

The ogres of Buddhism

There are a few fascinating tales of ogres entwined with the history of Buddhism, and they brilliantly show just how much the stories have served to shape the world. According to Atlas Obscura, Kyichu Lhakhang temple dates back to the seventh century, and it's still one of the most sacred sites in Bhutan. It's one of the oldest, too, but it didn't always look like it does today: It was originally much smaller, and legend has it that it was one of a series of temples that were built in a single night, in order to stop the relentless, onward march of an ogress determined to put an end to Buddhism.

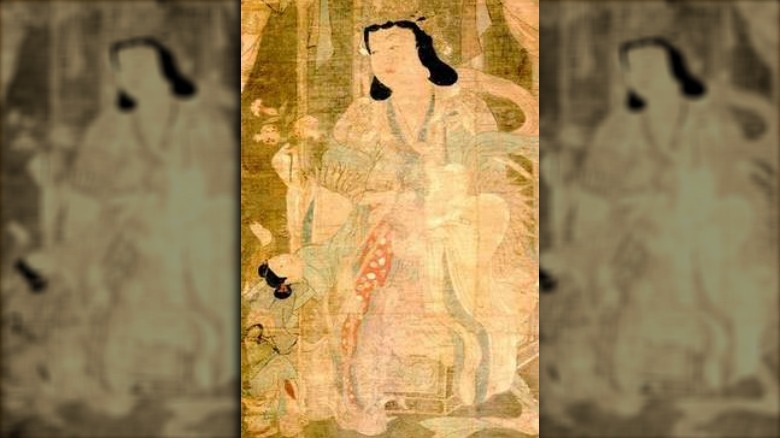

Not all ogresses were irredeemable: The Hindustan Times says that one was reformed into a figure that has been one of India's most important Mother Goddesses, Hariti. Originally, Hariti was a female ogre who feasted on the children of others, until losing her own. With the help of Gautama Buddha, she came to realize that the pain she felt was the same pain she had been inflicting on other parents. She was reformed into a goddess, particularly devoted to the care of children and to protecting them against death and disease.

Sometimes, they're shapeshifters

Shapeshifting might seem like it should be staying firmly in the realm of mythical creatures like vampires and werewolves, but strangely, some stories give that ability to ogres, too.

"Folktales and Fairy Tales: Traditions and Texts from around the World" says some ogres have a default human appearance, but if they fail to lure their human prey in with their perfectly ordinary ordinariness, they can shapeshift into a creature that's going to make hunting humans much easier. Most of the time, that was a crocodile, lion, or other big cat, but there's one set of traditions that's way different.

Alice Werner's collection, "Myths and Legends of the Bantu," includes (via Sacred Texts) an entire chapter on "The Swallowing Monster," and here's where ogres show up. Swahili stories say that when ogres are reincarnated, they become giant pumpkins, growing from vines that take root in the spot they fell. Folklorists suggest that's also the origin of a massive gourd from a tale from Usambara, which basically says that outside of a village was a gourd that grew bigger and bigger, until it swallowed everyone in the village. Only one woman was spared, and after the gourd retreated to a nearby lake, she gave birth to a son.

Once he got older and found out what had happened to his father and the rest of the village, he taunted the gourd until it came out of the lake. That, of course, is when he killed it.

So, what's the difference between an ogre and a cyclops?

The answer to the difference between an ogre and a cyclops is, surprisingly, "less than you'd think."

Odysseus famously went toe-to-toe with a cyclops while he was on his journey home, and when he first sees his adversary, Homer describes him (via Theoi) as "A monstrous ogre, unlike a man who had ever tasted bread, he resembled rather some shaggy peak in a mountain-range, standing out clear, away from the rest."

According to "Folktales and Fairy Tales: Traditions and Texts from around the World," one-eyed ogres occasionally do show up in folktales, but they're not the only version of ogre. Some ogres have three eyes, some have two, and strangely, some are specifically said to be cross-eyed.

Folklorists say (via the "Companion to Literary Myths, Heroes, and Archetypes") that one-eyed ogres could be considered the direct descendants of the cyclops, and that most tales that feature this particular type of giant are commonly found in the Mediterranean — although it does pop up in other areas, as in the Ngbaka story of an ogress named Un Oeil, or One Eye. They also suggest that ogres' seemingly chronic poor eyesight is another characteristic, one that forces some to hunt by the smell of their prey.

They came to the U.S. with help from Buffalo Bill

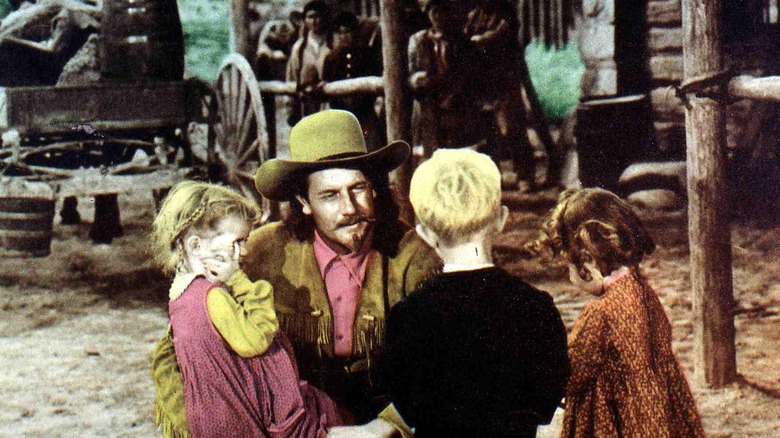

Ogres aren't usually thought of as being an American thing, but something strange happened with the widespread popularity of Buffalo Bill Cody — as discussed in the paper "Buffalo Bill and the Danish Ogres."

Cody kicked off his Wild West show in 1883, and, subsequently, dime store novels of his escapades became very popular. But it wasn't until the mid-1900s that Denmark became so enamoured with the idea that they started writing their own set of dime novels and added things that would make them look more familiar to European eyes. While American stories saw Cody facing off against "bad men and Indians," some of the Danish tales had him going toe-to-toe with ogres. In one, two men come across a third who has been badly beaten and lives just long enough to tell them about "a hairy giant ... murderers ... cannibals ... monsters ... of a dark cave."

They end up meeting up with their good friend Buffalo Bill and finding the cave in question. It's filled with an entire group of "ape-men" that meet the pretty standard definition of Beowulf-style ogres, and, of course, there's a daring shoot-out, and Buffalo Bill saves the day. At least it's a little more PC for these days?

St. Christopher was originally an ogre

St. Christopher is one of those famous saints that many people recognize: He's the patron saint of travelers, but less well-known is the earlier part of his story, when he was an ogre. The Eclectic Light Company looked at depictions of St. Christopher in the works of Hieronymus Bosch and suggests this particular part of the tales goes back to the 13th century.

His original name was Reprobus, which means something along the lines of "outcast" or "rejected." After spending much of his life trying to find the greatest king in the known world to offer him his service, he ended up spending some time with Satan. Until, that is, he realized that the devil was afraid of Christ, so he went looking for him.

When a hermit told him that the best way to meet Christ was to make use of his impressive strength and start helping people across a nearby river, he did — and one day, he helped a small child who got heavier and heavier as he walked. When he got to the other side, the child admitted that he was Christ, and he bore the weight of God and the world.

Reprobus changed his name to Christopher, which means "bearer of Christ," and in many old paintings, he'll still be depicted as an ogre. More specifically, the "Companion to Literary Myths, Heroes, and Archetypes" calls him a "converted ogre," suggesting that not all are inherently evil.

Santa was a what?

Santa Claus is the face of Christmas these days, but before that, he was known more widely as St. Nicholas. According to the St. Nicholas Center, he's also the patron saint and protector of children.

The story of how he became so closely associated with the protection of children is downright chilling. There's a few different versions of the story, but it features three children who end up in the clutches of an evil butcher who isn't one to pass up some meat, no matter where it comes from. So, he kills the children, slices and dices, and puts them in a massive salting tub to preserve their meat.

Seven years later, St. Nicholas comes, tells him to open the tub, and the three children emerge, perfectly fine. That's the more widely told version, and it's also the sanitized one.

According to the "Companion to Literary Myths, Heroes, and Archetypes," researchers point to a version of the tale where St. Nicholas doesn't immediately raise the children, and instead, he asks the butcher for "petit sale." But there's a catch: that translates both as "salted pork" and "salted flesh of a ... small child." That's led to a connection between St. Nicholas and other ogres who view eating children and piglets as pretty much the same thing, and that's led to an eerie interpretation of the whole Santa thing. St. Nicholas, the theory goes, is a reformed ogre trying to make amends for past misdeeds.

They may have been inspired by the bones of prehistoric men

Humankind has had a long history of looking at bones, trying to imagine what kind of creatures they came from, and then getting it really, really wrong. It's entirely possible that ogres were also inspired by something real, and according to the paper "Buffalo Bill and the Danish Ogres," that might be our Neanderthal cousins.

The paper notes that there's a lot of similarities between the appearance and personality traits of ogres and how people have historically viewed Neanderthals. For a long time, these so-called cavemen were viewed as bloodthirsty, unsophisticated, primal creatures that relied on brute strength to make up for non-existent intelligence. It's argued that the caricature of the "caveman" translated over into the ogre, and it's been written about by authors like Michael Crichton and H.G. Wells.

Electrum Magazine suggests there may even be more to it. They suggest that the very idea of ogres — along with similar creatures like trolls — may have come from sort of a vestigial memory. "Modern" man coexisted with and sometimes interbred with Neanderthals, so it's entirely possible that our collective, historical consciousness has held onto that relationship and created the ogre and the troll from it. Weird, right?

No one's really sure what's up with Bern's child-eating ogre

It takes a lot of effort to design and build a massive statue in the middle of a city, and that makes it pretty hilarious that the Swiss city of Bern has no idea why the heck there's a huge statue of an ogre in the middle of their city. Culture Trip says it's actually one of the city's oldest monuments. It was built in the 16th century, but no one knows what it's supposed to be.

There's theories, though, and one suggests it's depicting the brother of the city's founder, who was so jealous of his brother's popularity that he decided to eat all the town's children. (There's no evidence this actually happened, but still, that's no reason not to tell a great story.)

Other theories suggest it's meant to be a visible reminder to local children: Behave, kids, or the Kindlifresser is going to get you! (Parenting was a different thing back then.) Yet another theory is that it's Chronos, the titan from Greek mythology, and there's another that's more disturbing than all of those put together. Atlas Obscura points out that the ogre's hat bears a resemblance to the hat the city's Jews were forced to wear at the time the statue was built, so it's possible that it's full of raging anti-Semitism and a public reminder of just how evil Jews were thought to be. Kinda hoping it's not that one, right?