Extinctions That Scientists Still Can't Explain

There is a laundry list of different animals that have gone extinct through history. Sometimes, those extinctions come as a part of mass extinction events, of which there are five that are usually recognized (or six, if you count the current day). Other times, extinctions are fairly isolated events caused by local changes in the environment. And there are all the species that have gone (or are about to go) extinct because of human activity, such as the dodo.

Of all these kinds of extinctions, there are some that we understand more than others. Perhaps best known, there's the asteroid that took out the dinosaurs and a bunch of other life forms at the same time. Sometimes, though, things are a bit more mysterious, and scientists don't actually know how some extinctions have happened. In some cases, there are just too many competing theories and factors, and the actual cause of extinction is a complex mess of a bunch of different things. In other examples, it's because researchers don't have enough information to make any sort of solid guess.

There are still massive holes in our understanding of the evolution of life on Earth, and some extinctions are mysteries. These are some extinctions that scientists still can't explain.

The Tully Monster is shrouded in mystery

How about an ancient animal that's just so absolutely bizarre that it's called a monster? That's one way to describe the prehistoric animal Tullimonstrum gregarium, or Tully Monster for those of us less versed in Latin.

Based on fossils that have been dug up around Mazon Creek, Illinois, the Tully Monster looked something like a large slug. Instead of a mouth, it had a trunk-like appendage that ended in something resembling a claw. As for its eyes? Well, those rested at the end of two rods that seemed to extend out from the side of its body. It's a strange looking creature, to put things lightly.

Scientists really don't know much about it, though. After its remains were found in the 1950s by Francis Tully, it's mainly remained a mystery. YaleNews explains that it is near impossible to actually classify. Maybe it did have a spinal cord, or maybe it didn't, (via the Conversation). Some studies claim that the creature had a structure that functioned like a primitive backbone, though chemical analysis likens it more closely to invertebrates.

Basically, there isn't much that scientists know about this animal. The fossils are about 300 million years old, but researchers haven't figured out when the animal first appeared, much less when or how it went extinct.

The Christmas Island Pipistrelle was allowed to go extinct

It is easy to think of extinctions as things that happened to ancient, prehistoric animals, but the reality is that extinctions are very much still a thing in modern times.

The Christmas Island pipistrelle is one example. These little bats had been flourishing well enough for years on Christmas Island. But that all changed around the mid-1980s, when numbers started dwindling for no clear reason (via Mongabay). As the decades went on, those numbers just kept on falling, and by 2009, researchers estimated that there were only about 20 Christmas Island pipistrelle's left. An expedition launched later the same year found only a single bat, and the species was labeled extinct.

The exact cause for extinction is still up for debate. Invasive species of snakes or cats could have been the cause, or maybe it came down to disease (though researchers couldn't find evidence of any). A review of "A Bat's End. The Christmas Island Pipistrelle and Extinction in Australia" in Journal of Mammalogy also mentions factors like pollution and the destruction of natural habitats.

For some, the bats' extinction is a result of government mismanagement. According to Mongabay, Australian officials had been made aware of the decline in numbers, but didn't really act. Plans were proposed to help save the species, only to lack any sort of real funding or support. Officials delayed making any decisions, and by the time a plan was decided on, it was already too late to do much.

A bunch of sharks went extinct 19 million years ago

One of the really funny things about science is that, sometimes, crazy revelations come about by complete accident. That was the case when a couple of researchers discovered a previously unknown mass extinction of sharks some 19 million years ago (via IFLScience).

The team was studying the ratio of shark fossils to fish fossils throughout history. Long ago, there were about five fish fossils for every shark fossil, but 19 million years ago, that changed. Instead of a five-to-one ratio, it was almost a one-hundred-to-one ratio — an over 90% decrease in the shark population.

Researchers admit that they aren't really sure why this happened. That time period doesn't appear to have had any especially interesting change in climate or environment that would be obviously connected. It just seems like some sharks weren't as well suited to the environment as other animals.

Doubly weird is the fact that, as far as anyone can tell, only sharks were affected by this strange extinction event. No other marine life seemed to experience this same, sudden change — oddly selective sounding, right?

But perhaps it wasn't an extinction. Per New Scientist, the team was looking at a lesser-studied type of shark fossil; maybe the extinction event was just a change in biochemistry, with the new fossils being less well preserved.

What happened to Dickinsonia?

Many prehistoric animals were weird. Sometimes, they didn't even look like animals at all! Consider life in the Ediacaran era, around 600 million years ago. Ediacaran creatures didn't look like any animal we'd recognize today. Per Scientific American, they tended to look more like fronds and leaves, tubes, or pillows. Soft, squishy, and not really capable of active movement, they puzzled scientists for a long time. But in 2016, a mummified Dickinsonia (which tended to leave fossilized imprints that look ribbed and pancake-like) seemed to prove that the Ediacarans were actually animals, not plants.

As for what happened to them, there are a couple theories. Science Daily mentions that the Ediacaran extinction coincided with a massive advent of marine anoxia, or a sudden disappearance of dissolved oxygen in the oceans. Given that most animals need oxygen to survive, a sudden lack of breathable air seems like a good candidate for the cause of a mass extinction.

But there's another theory connected to the fact that the Ediacarans disappeared right around the time of the Cambrian explosion, or the sudden diversification of animal types, many of which could move around on their own (including mollusks, jellyfish, and vertebrates in general). Vanderbilt University explains that the Ediacarans might have just found themselves at a distinct disadvantage, either killed by new predators, or else just passed by, with new animals finding themselves much better suited to survival.

There are a couple reasons why the woolly mammoth might have gone extinct

The woolly mammoth is a pretty distinctive animal — one that you've probably seen images of since you were young, in textbooks or museums. According to Business Insider, they only went completely extinct about 3,700 years ago, well after humans had already begun leaving their mark on the world.

Although they disappeared relatively recently, the reason for the woolly mammoth's extinction isn't clear. Live Science tells us that the mammoths were doing their best somewhere between 30,000 to 45,000 years ago, during a slightly more moderate era of the Ice Age. Between then and the mammoth's extinction, the climate changed a lot, getting colder for a spell, then steadily warming. The theory goes that with the warming of the Earth, the mammoths started losing their preferred habitats, getting stuck in places like peatlands and forests, neither of which were super agreeable to them.

But the mammoths also had to contend with humans, who were spreading further across the globe and hunting around the same time. Looks like a pretty important argument for why the mammoths disappeared.

The actual answer is probably some combination of the two, though the details are hard to work out. Mammoths were actually around when the Earth was about as warm as it is now, and also lived alongside humans in Asia for thousands of years without disappearing. (Conversely, they started dying out in North America before humans ever even arrived.)

The fate of the Neanderthals

For all the interest about humans' recent relatives, there's incredibly little consensus about what happened to the Neanderthals. They disappeared abruptly about 40,000 years ago, but the reason is basically unknown.

There are a ton of theories. There's the possibility that Neanderthals aren't entirely gone, having interbred with our ancestors, meaning that some of us actually carry Neanderthal DNA. But, according to Nature, only a very small percentage of people have Neanderthal DNA. Neanderthals may have just lost out to humans, who had more sophisticated social structures, such as trading networks between different groups, as well as more advanced technological advances, like clothing or inventive tools, per Smithsonian.

Then again, maybe competition wasn't directly the problem. Maybe climate change did them in, messing with their habitats, which they were very specialized to thrive in. When those specific conditions disappeared, they might not have been able to adapt in the same way that humans could (again, trading systems and technology could make up for a lot).

The Guardian points to simple bad luck as a possibile cause of extinction. Birth and death rates naturally fluctuate; their numbers might have just been on the decline. The arrival of humans, who split up their populations, could have just sped up a natural process. Stanford also raises the possibility of disease being the culprit. Humans might have introduced illnesses to Neanderthal populations, inadvertently killing them off.

The mysteries of the Late Devonian mass extinctions

When you get into the territory of mass extinctions, the Late Devonian mass extinction is a confusing one. This isn't something like the event that wiped out the dinosaurs (an asteroid hitting the Earth). In this case, you've got a bunch of extinction events that all took place during the Devonian era (360 million years ago).

Because these extinctions take place over a relatively long span of time, there isn't one clear factor that really caused this massive loss of life. ScienceAlert reports that analysis of spores found that a lot of plants had been subject to high levels of UV radiation. That radiation damaged the plants and could have caused mutations, killing off a bunch of plants in the long term (which then would have a widespread negative impact on the food chain as a whole). As for where all that extra UV radiation came from? Potentially a hole in the ozone layer due to global warming.

Devonian Times presents something different, though. The Devonian Plant Hypothesis basically says that the expansion of plant life on land might have depleted dissolved oxygen in the oceans (doing a number on marine life), but also, through a bunch of complicated processes, reduced carbon dioxide in the air. The result? Global cooling, which created glaciers and lowered sea levels.

Or maybe there was a meteor impact. There's chemical evidence of that, too (via Britannica).

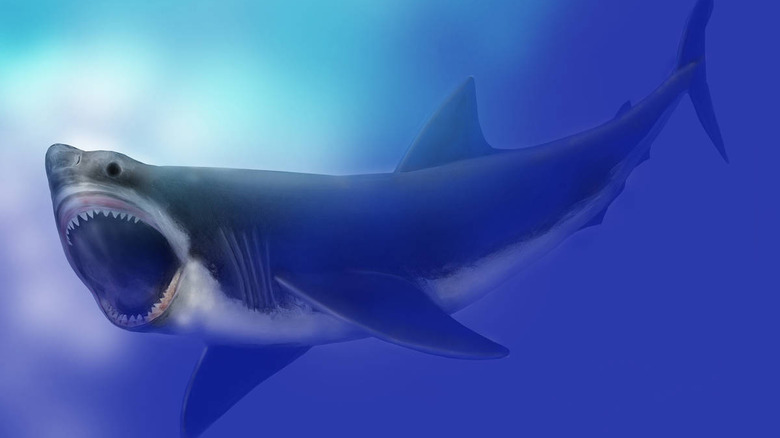

Megalodon's killer might still be around

If you're not sure what the megalodon was, just think of a gigantic shark about 50 feet long, and you're on the right track. But what in the world could make something so huge go extinct?

For a while, scientists thought that the megalodon went extinct 2.6 million years ago, just one victim of a marine mass extinction, according to ScienceAlert. The exact reason for that extinction is debatable, but theories sometimes cite a supernova as the cause. Smithsonian Magazine explains that said supernova might have flung a bunch of radiation at the Earth; from there, climate change just had to do its work, wreaking havoc on the oceans.

But the megalodon population had already shown itself capable of surviving changes in climate, so maybe something else was to blame (via Britannica). Like changing dynamics in the food chain.

More recent research has brought up the possibility that scientists have been reading the fossil record wrong all along. Younger fossils had been incorrectly dated, so perhaps the megalodon actually went extinct a million years earlier. At the same time, great white sharks had just spread across the globe, potentially becoming competition for the megalodon, which was suffering from a possible food shortage. Granted, placing your bets on the great white shark being the only culprit here might be kind of premature (plenty of other things could have played a role, too), but at the end of the day, the megalodon might have just been beaten out.

There's basically no information on the broad-faced potoroo

Long story short: we basically know nothing about this animal.

The broad-faced potoroo was a part of the family of rat kangaroos, according to Britannica, and it has been labeled as extinct since 1982, though the last observed member of the species was found around 1875 (via Australian Government).

Now, are you ready to become an expert in all the first hand knowledge we have of this animal? Read this: "All I could glean of its habitat was that it was killed in a thicket surrounding one of the salt lagoons of the interior" (via "A Gap in Nature: Discovering the World's Extinct Animals"). That's a quote from John Gould, and also our complete knowledge of the broad-faced potoroo in its natural habitat. No joke — that's it. Only 12 specimens were ever collected, two of which were skinned in 1912 by a museum that then proceeded to throw out the rest of the body. A bunch of DNA, diet, and anatomical information was lost to the garbage.

Unsurprisingly, we don't know much about the cause of this creature's extinction either. The settlement that would become Perth had only been established a few decades earlier, so land clearing probably hadn't destroyed their habitat. Feral cats might have done them in, or maybe it was tied to the ending of Aboriginal burning (a traditional form of fire management).

The Rocky Mountain locust wreaked havoc, then disappeared

These pests were basically the bane of Great Plains settlers in the late 1800s. A review of "Locust: The Devastating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect that Shaped the American Frontier" gives a little glimpse into the abject fear that these bugs could strike into the settlers' hearts. Once incredibly abundant, Rocky Mountain locusts would gather into massive swarms that resembled glittering dark storm clouds before descending to devastate crops. This was a regular occurrence, but it was worse during years of drought, as was the case in the 1870s, when many people ended up on the brink of starvation. Things were bad, but a few wetter years put a temporary stop to locust invasions.

Except it wasn't temporary. Come the next period of drought, the locusts were just gone.

The why is up for debate. Some people have tied the locust population to the bison population. Maybe the bison helped the locusts survive, so dwindling bison populations killed off the locusts. Or maybe the settlers were more involved in the extinction than they thought, inadvertently destroying the habitats of these locusts, which were eventually forced to seek shelter in smaller areas, and consequently shrunk in numbers (via High Country News). On top of that, the plowing of the soil might have made it impossible for the locusts' eggs to hatch; new locusts couldn't be born, and others might have been killed by alfalfa, which is harmful to them.

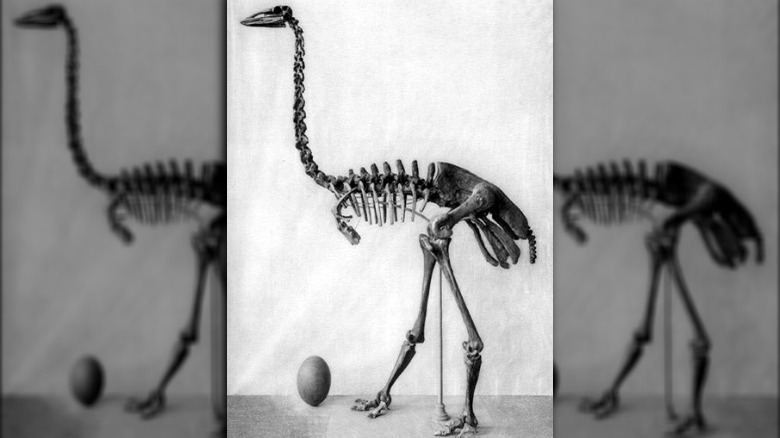

The confusing history of the elephant bird and human settlement

As Forbes explains, Madagascar was unique in terms of the history of human settlement worldwide. It took a relatively long time for humans to find their way to the island (the first settlers showed up around the year 500), which made the island a safe haven to exotic creatures like the gigantic elephant bird.

These 3-meter-tall birds (via BBC) went extinct about 1,000 years ago — around the time of human settlement on the island. People brought more fires, and forests were turned into pastures for cattle. Between hunting (of both adult birds and their eggs) and a loss of habitat, it seems like early settlement is to blame entirely for the loss of the elephant bird.

But things might not be that simple. Elephant bird fossils were found marked with strange scratches from stone tools likely made by humans. All of a sudden, it sounds like humans were living peacefully alongside elephant birds for thousands of years, without the birds ever going extinct. So the introduction of humans may not have done the birds in, and, according to Kristina Guild Douglass on Yale's website, the only major interaction between the two groups was some poaching of the eggs.

Settlement and farming likely did hurt the elephant bird, though the specifics are hazy. Douglass suggests some combination of climate change, habitat change, and human interaction as the possible cause of the bird's extinction.