The History Of The Golem Explained

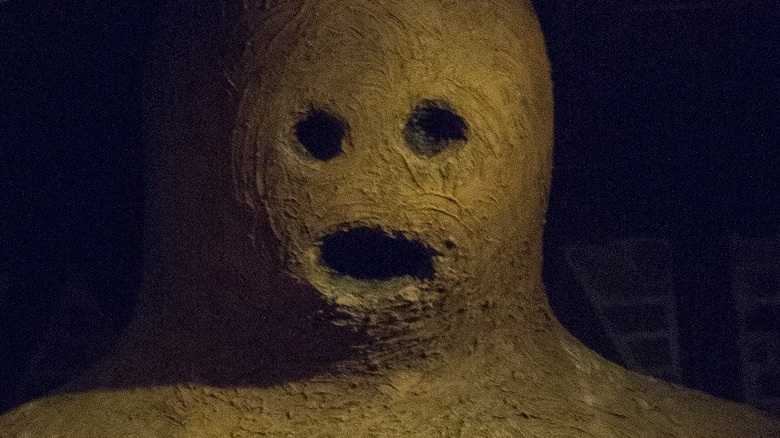

Steeped in Jewish folklore, the basic story of the golem typically follows a given path: a highly intelligent, learned person — usually a rabbi — creates a being out of clay to serve the Jewish community. That being is then given a sort of quasi-life after a person carves or otherwise installs a mystical phrase like the secret name of God onto the creature's body. It awakens as a golem. Though silent, it's tremendously strong and not terribly thoughtful. Often, something goes awry, like a poorly worded command, and the golem turns from a helpful protector to a community menace. Its creator is then forced to put the creature down, often by altering its life-giving inscription.

Simple enough for a bedtime story, sure, but a little bit of extra digging will show that there's more to the golem legend than a poorly considered creation gone wrong. There are threads within the many golem stories that link back to mysticism and hidden knowledge, while others discuss the meaning of what it is to be alive. Many more hinge on the hubris of people, even very wise and respected ones, who think that they can take on the creative work of God and come out unscathed. And, on a more practical level, the golem has since grown into a figure of Jewish resistance and strength, given that many tales have it protecting vulnerable Jewish communities throughout the ages. The history of the golem is, in short, rich, complicated, and ripe for investigation.

Tales of golems go back to the very beginning

In its earliest, simplest form, "golem" is a descriptive word used to refer to a being that's half-formed. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, in some interpretations of early Jewish texts, Adam himself is referred to as a golem, but he's not a man made out of mud wreaking havoc in Paradise. Instead, the term refers to his first few hours as a "shapeless mass," long before his limbs were formed, or he was granted a soul by God. It makes sense, given that he was said to have been shaped from the clay of the earth.

Other religious texts like the Bible briefly refer to embryos still growing in the womb as "golems," again referencing their half-formed, pre-human nature. Psalm 139:16 says that "Thine eyes did see my substance, yet being imperfect." The word "substance," in some versions, is translated as "golem."

The Jewish Virtual Library notes that some portions of the Talmud hint at golems that were made not by the Almighty, but by very learned humans like the prophet Jeremiah. Then again, there's always the chance that these very early legends aren't referring to a quasi-man that's made out of clay and animated by magic but are instead talking about a metaphorical spiritual transformation. And it's important to note that, while Adam was said to be created by God and so imbued with a soul, golems created even by the holiest and wisest of men lack that divine spark.

The golem really began as a Jewish folklore figure

If we're not talking about linguistic details or literary flair, then the figure of the speechless, clay-based "golem" doesn't really appear until long after the Talmud had established itself as a religious document and even after the newer Bible gained a foothold amongst Christians. For the concept of a creature made from soil, created by humans, and meant to serve them, we'll need to turn to the Sefer Yetzirah (or "Book of Creation"). This is one of the earliest known books to deal with Jewish mysticism and secret knowledge, per Britannica.

Except that Sefer Yetzirah itself won't have a ton of direct information about the nature of golems. Instead, as the Jewish Virtual Library notes, we'll have to turn to rabbinical commentaries on the Sefer Yetzirah, where religious leaders added their own gloss to the original text, which appear to contain a pretty clear definition of a golem amongst them, along with less clear instructions for making one. Most interpretations of the Sefer Yetzirah's guide to creating a golem center on forming a human shape out of clay or dirt, then using the hidden name of God to bring the figure to life — or at least its strange half-life. And it's pretty clear that, while the original mystical texts of Judaism don't necessarily contain a ton of information about golems, the creature has since gained quite a life in the Jewish folklore and oral traditions of Europe and beyond.

How are you supposed to make a golem, anyway?

Making a golem is a tricky process that's almost impossible to get right, even for the most careful holy people who take on the task. And, going by the various legends of golems that have been successfully brought into the world, you might regret creating one anyway.

But, if you're really interested, there are some instructions out there in texts like the mystical Sefer Yetzirah and rabbi's commentaries therein. Per the Jewish Virtual Library, these usually start off with a directive to shape a human form out of soil or clay. You, either alone or with a group of similarly holy and learned people, need to then walk around the lifeless form, chanting incantations typically made up of letters from the Hebrew alphabet and also the secret name of God.

As "The Golem Redux" notes, some variations of these instructions also say that you need to inscribe certain letters onto the golem, usually spelling out emet or "truth" on the creature's forehead. And, when the golem inevitably gets frighteningly strong and starts to run out of your control, erasing a single letter in that sequence changes the word to met — "death." Otherwise, you might write God's name on a bit of paper and place it in the golem's mouth. To subdue an unruly golem made in this way, you simply need to get close to the raging, powerful creature and remove the tiny scrap of parchment from its mouth.

One of the oldest tales of a manmade golem comes from Poland

Amongst scholars, the oldest known story of a soil-based golem made by a human comes to us from Poland. Specifically, Chełm, a Polish town where, in the 16th century, legend maintains that Rabbi Elijah Ba'al Shem created the infamous Golem of Chełm.

According to a video released by Cztery Strony Bajek, Rabbi Shem was an incredibly wise and well-educated religious leader who was also exceedingly well versed in the mystical Kabbalah tradition. He was so well educated, it seems, that he created a clay-based golem to serve and protect the Jewish people of Chełm. But, setting off a narrative streak that would last for centuries, the golem proved to follow instructions too literally. When asked to collect wood, for instance, the golem attempted to chop down an entire forest. The golem was also seen to be growing larger and stronger than it had been originally created.

To fix the problem, Rabbi Shem was at least still able to use his smarts to end the golem's existence. "The Golem Redux" reports that, in the legend, the rabbi asked the ever-taller golem to lean down and help the rabbi remove his shoes. Rabbi Shem quickly wiped away the letter aleph from the golem's forehead, turning emet (truth) to met (death). In some versions, the rabbi survives, while in others, he's crushed by the weight of the falling, insensible golem — and also metaphorically by his own hubris.

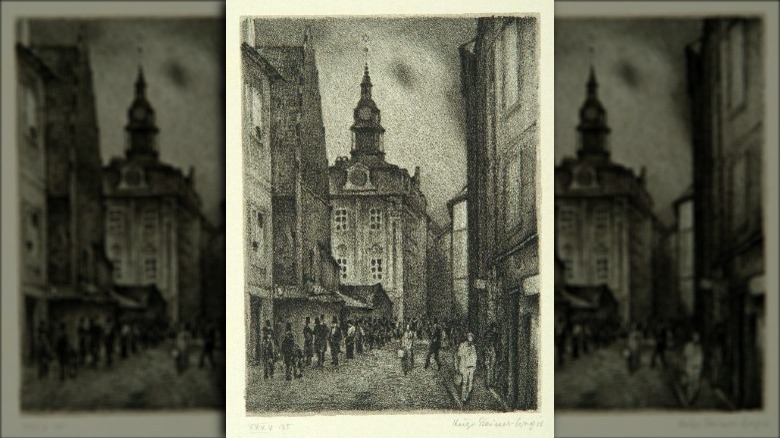

The most famous golem story is set in Prague

Ultimately, there's no escaping the most prevalent and often retold story of the Golem of Prague. In fact, the golem in question is so well known that it's hard to visit Prague without seeing his image somewhere. According to The New York Times, people can see a golem musical, dine at the Golem restaurant, and buy any number of different golem figurines.

The Jewish Quarterly Review argues that the story of Prague's golem is heavily influenced by the earlier tale of the Golem of Chełm, Poland. Only, this time the rabbi at the center of the tale is Rabbi Judah Loew, a real man who was so renowned for his learning that he gained the title of "maharal" derived from his status as a respected teacher.

As the story generally goes, Rabbi Loew created the golem to serve the Jewish community of 16th century Prague, which was beset by antisemitism. He took clay from a nearby river and built the golem, inscribing emet on the creature's forehead. The golem went on to do both mundane and wondrous things, from protecting the people in the Jewish ghetto to summoning the spirits of those who were long dead. Eventually, the golem went on a rampage, tearing apart the Jewish community, and Loew was forced to smear the clay inscription to met. The remains of that golem are rumored to be in the attic of the city's Old-New Synagogue, which still stands today.

The golem has been used as a symbol of Jewish resistance

In many retellings, the Golem of Prague doesn't just fetch water or chop wood, but also stands between the Jewish people and violent antisemitism like the "blood libel." Per the Atlanta Jewish Times, the blood libel was a lie concocted by fanatics who claimed that Jewish people used Christian blood in secret rituals. It wasn't true, of course, but that didn't stop the blood libel tale from spreading and being used as an excuse for real violence. At least, in some legends, the golem was there to defend the Jews of Prague against the lie and sometimes was able to produce supposed victims of the blood libel.

Unfortunately, antisemitism and the desire for a metaphorical protector haven't faded nearly as much in the intervening centuries as some would like to believe. At LitHub, Nathan Goldman notes frightening modern trends in American politics, notably ones that depersonalize and denigrate Jewish people themselves as subhuman "golems." But what if that attempt to weaponize the golem backfires and, as in other eras, the creature is instead used as a symbol of Jewish strength, resistance, and resilience? It could be that, as far removed as we are from the Prague of Rabbi Loew or the Chełm of Rabbi Shem, the golem is still very much a figure in play. Yet, instead of being just an example of hubris and mysticism gone wrong, the golem has become far more than a mindless menace.

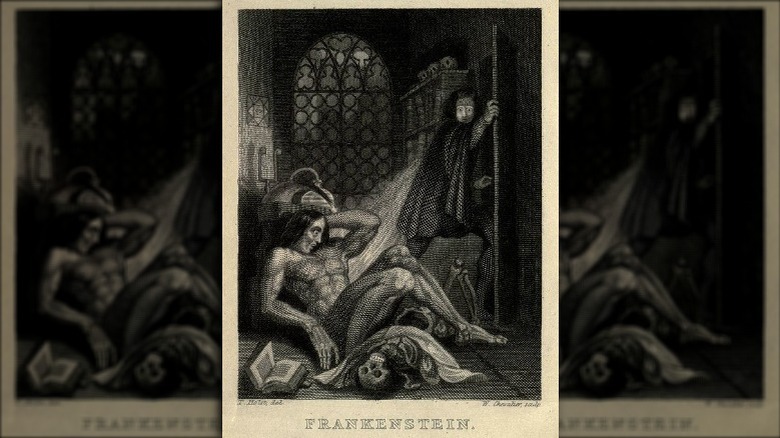

Tales of the golem have been linked to Frankenstein's monster

Taken broadly, there are some clear narrative parallels between classic tales of the golem and the quasi-human creature created by an unstable scientist named Victor Frankenstein. There's no real evidence that author Mary Shelley drew upon Jewish folklore when writing her 1818 novel, "Frankenstein," but consider the basic plot — a brilliant human creates life that eventually grows too powerful and turns against its creator and the rest of the world. The learned rabbis of legend would probably be able to commiserate (or argue) with Victor Frankenstein at length. And Frankenstein's monster, who names himself Adam (after that initial Adam who was first made from clay), bewails his imperfect form. If the golem could speak, would he say something similar?

Tablet notes that there's more to this connection than surface level similarities, however. Rabbi Loew's involvement with the story first arose not in the 16th century, but the 19th, when people seemed to be primed to look for characters who defied the laws of nature. Literary scholars and writers, not all of whom were Jewish, encouraged the rise of this fantastical creation tale. It was the tail end of the Enlightenment, after all, when anything must have seemed possible, even a man made from spare body parts or simply the clay of the earth. And Prague, with its reputation for the mystical and penchant for pushing boundaries, was just the right city for the Romantic-era golem to call home.

Writers have mined the golem story for centuries

With its grand themes of creation, hubris, and mystical knowledge, the golem legend has proven irresistible to writers and other creative people over the centuries. There's a universe of golem literature out there, to the point where Slate wondered if it was necessary to add more entries to the canon.

The modern golem novel seems to have been around since at least 1997, when "The Puttermesser Papers" by Cynthia Ozick debuted. Its tale centers around the life of a seemingly ordinary woman, Ruth. In one episode of the novel, she creates a golem — who is also a female creature named Xanthippe, breaking with the male-coded golems of legend — who ultimately helps Ruth become elected mayor of New York City (via My Jewish Learning). But Xanthippe, like so many of her golem cousins, just cannot control herself and eventually begins to undo the work of her creator.

Since then, there's been a wide array of novels about the golem, from the semi-comic "The Golems of Gotham," to the less obvious parallels with the golem story written by Michael Chabon in "The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay." Even Rabbi Loew got some time in "The Book of Splendor" by Frances Sherwood, which also involves a romantic plot between a woman and Loew's golem. It all led Slate to wonder if we were finally getting golem-ed out, but it seems plain that we're not done reading about the golem just yet.

The golem is the big star of a silent film classic

If the golem has been so successful on the page, then it's also found some success on the screen. Even a casual student of golem lore will inevitably come across "The Golem," the 1920 silent film that has left an indelible mark on the legend of the golem long after its premiere. It's also one of the acknowledged classics of German Expressionist film, which helped to usher in a more dramatic, artistic era of movie making. Seriously, the looming clay figure and the oversized Dutch boy haircut on the golem at the center of the film is so iconic that it's even been cribbed by "The Simpsons" for a segment of their Halloween-themed "Treehouse of Horror XVII" episode (via IMDb).

Actually, as the State University of New York notes, the 1920 film is only one of three golem-focused films made by German director and actor Paul Wegener. He first made 1915's "The Golem" and, two years later, released the more comedic "The Golem and the Dancing Girl." However, both films have since been mostly lost, though it's possible to view clips of both. Wegener himself played the titular golem, which is clearly influenced by the Romantic-era tale of the Golem of Prague. Wegener's golem is more conscious and self-aware than perhaps any other representation of the creature before, bringing a hint of pathos to the surviving 1920 film and drawing the golem legend closer to humanity.

Modern people see a link between artificial intelligence and the golem

So, with the golem having now traveled from the beginnings of religious scriptures to early modern Europe to today, where does this figure land in our cultural landscape?

Look to machines imbued with artificial intelligence. Writer Isaac Bashevis Singer put it pretty adroitly when he asked, "What are the computers and robots of our time if not golems?" (via The New York Times). Though Singer wrote those words back in 1984, they ring just as true today, when machine learning and artificial intelligence are even more embedded in our reality.

In some legends, the golem takes lessons very literally, to the point where a poorly-worded command will leave it attempting to chop down an entire forest. Is the golem at fault here, or should those who commanded it think more carefully about their roles? And is the situation really all that different from Tay, the Microsoft-based Twitter bot that, after drawing upon the example set by other Twitter users, became overtly racist and aggressive in a single day, according to The Guardian? Microsoft, which quickly shut Tay down and began deleting the worst of its tweet, later told Inverse that "Tay is a machine learning project, designed for human engagement. It is as much a social and cultural experiment, as it is technical." It's a powerful analogy for both the power and risk of creating something like life without full intelligence, much like the early legends of the golem.