Islands That Hold Dark Secrets

There's something innately chilling about an island, especially those in the middle of the oceans, miles from anywhere. It's probably the lack of places to run. Islands have had a rather ominous place in history — particularly American history — for a long time.

One of the nation's most enduring mysteries involves the disappearance of the settlers of Roanoke Island, but here's the thing: It's not really a mystery. Let's talk about this now, and get it right out of the way. In 2020, the Croatoan Archaeological Society — a conglomerate of researchers from places like the University of Michigan and the University of Bristol, England — published a book (via Vice) that aimed to put the whole mysteriously disappearing settlers thing to rest. Sure, it's a great story, but researchers say there was no slaughter, no mass die-off, and definitely no alien abductions. Their findings suggest that the settlers were never actually missing in the first place — they'd simply moved in with local Indigenous peoples and lived happily ever after.

That's not as great of a story — aside from, ya know, for the people who lived it — but don't worry. There's no shortage of islands that are still harboring some chilling secrets... so let's talk about those places.

The terrifying fate of one of America's most famous pilots

The mystery of Amelia Earhart's fate is one of the most enduring in American history, and the story isn't over yet. In 2019, National Geographic reported on a major expedition to Nikumaroro Island, an island in the Pacific that has long been rumored to be one of the likely locations that Earhart may have landed.

Did she? It's still not clear, but we do know that something happened on the island. Way back in 1940 — just three years after she and navigator Fred Noonan disappeared — a set of bones were discovered on Nikumaroro, along with a few other signs someone had been on the otherwise uninhabited island. But who? The Guardian says that the bones have since disappeared, but using the measurements taken back in 1940, some think they're Earhart's. Without the actual bones, though, it's impossible to tell.

So, let's go back to the island, and the question of whether or not there's anything else left there to discover. Maybe, but the reason it might be tough is that the island is swarming with coconut crabs that are 3 feet across and have claws capable of dishing out serious pain. When the expedition left the crabs a pig carcass to see what they would do, they stripped it clean and scattered the bones, dragging some to their underground burrows. Was that what happened to Earhart? Forensic dogs have confirmed that yes, someone died there... but who?

What's with the strange burials of Chapelle Dom Hue?

History is strange sometimes, and archaeologists are often left scratching their heads over some weird findings. "What on earth would have possessed people to do this?" is the question of the day when it comes to the graves unearthed on the island of Chapelle Dom Hue.

The little island is off the coast of Guernsey, and when archaeologists were excavating it in 2017 (via the BBC), they came across a weird burial. One might expect human remains, but they uncovered the remains of a porpoise estimated to have been buried there at some point between 1416 and 1490. What would have prompted people to have buried the porpoise? Researchers suggest it may have been killed and buried as part of a ritual, or in an attempt to preserve the meat for future meals. And that's not the only weird burial archaeologists have uncovered: just a few feet from the dolphin were the remains of a human skeleton that was — disturbingly — missing hands (via LiveScience).

Other areas of archaeological interest suggest that the tiny island — which is only about 50 feet across today — was once home to a few Christian monks. Some suggest the man was a monk who lost his hands to leprosy, while others think the corpse just kind of washed up on shore. Still, inquiring minds want to know: What the heck?

What killed the men buried on Beechey Island?

According to Secret of the Ice, archaeologists who visited the site where several men had been buried in the icy ground of Beechey Island found more questions than answers. The men were a part of the Franklin Expedition, a well-equipped and well-funded 1845 exploration party that had headed north to explore the Northwest Passage. Simply put, they headed out, stopped in Baffin Bay, and then... that was it.

Since they had enough supplies to last around three years, it was that long before anyone started to worry. Retracing the route of the expedition started turning up abandoned camps, trapped ships, notes and journals confirming the deaths of expedition members (and some good, old-fashioned cannibalism), and graves, like the ones on Beechey Island. Fast forward to the 21st century, and it's still unclear just why so many people died so quickly, and why the expedition failed in such spectacularly bloody fashion.

Excavations of the bodies led to clues pointing to tuberculosis and lead poisoning, but that explanation hasn't been a completely satisfactory or widely accepted one. There are a few footnotes, too: The three men died less than a year into the expedition, and one man, John Torrington, had wasted away to just around 85 pounds by the time of his death. Another — John Hartnell — had been autopsied before he was buried, suggesting the expedition's doctor wanted to know why so many of his crew were dying so fast and so badly.

What happened to the dead of Palmyra?

Any time there's mention of the word "curse," it's a cue for skeptics to scoff. But sometimes, there's so much to a story that it might make even the biggest skeptic reconsider.

That's the case with Palmyra, an island in the Pacific that's had way more death and tragedy than it should. It wasn't until 1802 that a ship called the Palmyra was wrecked on the atoll's rocky reef, and it got a name and a map entry. Things were quiet for around 70 years, until another ship — the Angel — also wrecked on the reef. A few months later, another ship sailed by... and kept right on sailing when they saw the brutally murdered bodies of the Angel's crew. Later, a pirate ship crew met an even more mysterious fate, and simply disappeared — and disappearances continued to happen up into World War II.

Then, in the early 1940s, Culture Trip says Malcolm and Eleanor Graham set sail on their boat Sea Wind. They headed to Palmyra, and it wasn't until 1946 that another couple found the burned skull and bones of Eleanor Graham, sealed inside a metal container. Her husband's remains were never recovered, although the Sea Wind did come sailing into Hawaii with another couple at the helm. Duane Walker was ultimately convicted of murder — but claimed it was self-defense — and when he died in 2010, the secret of what really happened to Eleanor and Malcolm Graham may have died with him.

How many people did Ratu Udre Udre really eat?

Ratu Udre Udre is in the Guinness Book of World Records for a disturbing reason: he holds the record for "Most prolific cannibal." That's a record that most might agree probably shouldn't be broken, but the weird thing is that no one's even sure how many people he's eaten.

Udre Udre was from Fiji, and these breathtakingly beautiful islands have so firmly embraced their cannibalistic past that according to Culture Trip, you can even buy cannibal-related merch in their gift shops. He lived on Viti Levu at the turn of the 19th century, and — like many of his fellow cannibals — he kept a record of the number of people he ate with the help of some stones. One stone represented one person, and when he was buried, more than 800 of his cannibal stones were used to decorate his grave (pictured). The problem is that some of the stones are missing, and no one knows how many.

Estimates suggest there should be at least 999 stones, and that's not even the darkest part of the story. It's not clear why cannibalism was so widely practiced, although some suggest it was done by tribal chiefs with the belief that they were going to absorb the power and life force of their victims' energy. Victims were often cut into bite-sized pieces while they were still alive, and the practice only ended in 1867, with the deaths of Reverend Thomas Baker and six student teachers.

The island of lost treasure, black magic, murder, and a sex cult

A Canadian clerk for Wells Fargo, Edward Arthur Wilson decided to quit his job, become a merchant marine during World War I, then reinvent himself as Brother 12, one of a "zodiac" of leaders of a group he called the Chela. It was their mission to follow The Three Truths and prepare for the end of the world — in a "fortress for the future" he claimed he had seen in a vision.

The Aquarian Foundation was created in 1927, and the charismatic Brother 12 convinced around 8,000 "adherents" to help contribute to his fortress, built along a series of islands starting with Vancouver Island. (Macleans says this was about the same time he convinced Myrtle Baumgartner he was the incarnation of Osiris, she was his Isis, and they were going to give birth to Horus the redeemer.)

What happened on the island and inside the cult is unclear, but according to BIV, some followers became disillusioned with his leadership. Stories were equally wild and disturbing: One claimed a young woman was murdered for being "unfaithful" to the so-called Brother 12. It's not known if that's true, but almost as disturbing is the amount of money Wilson took from his adherents. According to Global News, his Aquarian Foundation relieved members of their gold: By the time he disappeared, he had somewhere around 40 cases of quart jars, all filled with gold coins. None have been recovered.

What really happened to the Baroness?

The Galapagos might conjure images of giant turtles and Charles Darwin, but there's an even more fascinating — and weird — story that starts with Dr. Friedrich Ritter and his girlfriend, Dore Strauch (pictured), fleeing the rise of Nazi Germany to go live on one of the islands, called Floreana.

Ritter — who was, incidentally, the proud owner of a set of steel dentures — was a big fan of living the life of a vegetarian nudist, and here's where it gets weird. Letters Ritter wrote to friends back home ended up being published, and more people decided to join them — including the Baroness Wager de Bosquet and her pair of lovers. The Baroness arriving on the quiet slice of paradise was something akin to Eurovision setting up in the Vatican Library, and those who had gone to Floreana for the quiet life found themselves in the middle of plans to build a 5-star resort. Until, that is, the baroness and one of her lovers mysteriously vanished.

The Telegraph says that no charges were ever brought against anyone, but Ritter — the lifelong vegetarian — reportedly died after eating spoiled meat not long after, while cursing the name of his girlfriend to his last breath. Strauch left and returned to Germany, where she was committed to a mental institution and later killed when a bomb hit the hospital during the war. Whatever happened to the baroness, her lover, and the nudist vegetarian remains a secret kept by the island.

The fate of the lighthouse keepers of Eilean Mor

For a long time, the only inhabitants of the Scottish island of Eilean Mor (pictured) were the lighthouse keepers, tasked with keeping the beacon blazing and passing ships safe from the rocky coastline. In 1900 — on the day after Christmas — a ship carrying a replacement lighthouse keeper approached the island, only to get no response from the keepers. According to Historic UK, the replacement keeper, Joseph Moore, went ashore to see what the heck was going on. He found an open door to the lighthouse, a stopped clock, two missing coats (and one still hanging in its place), dinner on the table, and no keepers.

Three men had vanished without a trace, and further investigation turned up some disturbing details in the keepers' logs. December 12 and brought severe winds, they wrote, which had driven one man — a seasoned veteran of the shores — to tears. The storm continued, and they prayed for it to stop. On the 15th, someone had written, "Storm ended, sea calm. God is over all."

As if that wasn't eerie enough, nowhere else in the area had experienced any storms whatsoever. No one has ever been able to explain what happened to the three men or what their final entry in the logbook meant, but lighthouse keepers who took the post after their disappearance claimed — for decades afterwards — that on windy, stormy night, they could hear the names of the missing men being called on the wind.

The mysterious island black site linked to torture

It's no secret that the US has military bases all over the world, but the one located on the island of Diego Garcia — in the middle of the Indian Ocean — is one of the most remote and, says Princeton, "secretive" of them all.

There are a few levels of secrecy here, too, starting with the island's history. The book "Island of Shame" claims that the island's native people were kicked off their island home and forced to relocate to the slums of areas like the Seychelles and Mauritius. Meanwhile, questions have repeatedly been raised about what's been going on inside the base. In 2014, The Guardian wanted to know how complicit the UK had been in what they called "the CIA's torture programme," and said the details on what was happening to the 500+ prisoners there were incredibly murky.

In 2015, Lawrence Wilkerson — one of President George W. Bush's senior officials — confirmed that in the years after 9/11, the island had served a crucial role in interrogations. He told Vice that it was "a transit site where people were temporarily housed, let us say, and interrogated from time to time." He suggested holding facilities weren't long-term, and he continued: "So, you might have a case where you simply go in and use a facility at Diego Garcia for a month, two weeks, or whatever, and you do your nefarious activities there." What, exactly, has gone on there? No one knows, and no one's talking.

Is this where Geronimo's skull is?

The legendary Apache warrior Geronimo died at Fort Sill in 1909, and according to the legend, his bones were disturbed nine years later when a group of men stationed at the fort dug up his grave and stole his skull, a few other bones, and some associated relics. The men were reportedly members of Yale University's mysterious Skull and Bones society, and saw the remains moved to a secret location associated with the society.

NPR says that story was given credence in 2009. That's when Marc Wortman was researching a book about Yale students who fought in WWI and uncovered a letter reading (in part): "The skull of the worthy Geronimo the Terrible is exhumed from its tomb at Fort Sill by your club ... and ... is now safe inside the Tomb."

Skull and Bones members aren't talking, Yale says the university "does not possess Geronimo's remains," and stresses that they don't own Skull and Bones properties... which include an island in the St. Lawrence River. According to Thousand Islands Life, the society owns Deer Island, which is still regularly visited by society members. It's said to figure into new member rituals — including the kissing of a skull — and they further suggest that this might be the location of the elusive skull. Is there any truth to that? It's unlikely to be revealed: They add that activities on the island "are protected by a special act of the Connecticut Legislature."

Do the dead nourish the grass of Partridge Island?

Partridge Island is off-limits today, but Legion Magazine says that at one time, it was a bustling hub of activity. Starting in 1785, the island — officially part of Saint John in New Brunswick — would become the first immigration and quarantine station in North America. Immigrants from Europe would be treated to kerosene showers in an attempt to stop the flow of diseases like smallpox and measles, and most of the time, it worked. Sometimes, it didn't.

In the mid-1800s, so many Irish fled famine to try to find a better life in North America that the island became known as Canada's Emerald Isle (via Atlas Obscura). A Celtic cross was erected on the island in 1927, and it was built to acknowledge the journey made by the living, the dying, and the dead.

Over the course of the island's use as a quarantine station, it saw the arrival of immigrants from all across Europe and Russia — and so many were sick, starving, and destitute that it was impossible to keep track of just how many died. In addition to the island's six cemeteries, there were also mass graves. Legend says that the lushest, grassiest areas of the island are so green because of the bodies buried beneath them, and just how many suffered and died on the island — so close to a new life in a new world — has long been lost to everything but the ground they're buried in.

The island paradise with a history of child abuse

Pitcairn Island had the most fictional-sounding start in history: After sailors on the HMS Bounty mutinied, they settled down on Pitcairn with their brand new Tahitian wives and created a whole new civilization. It sounds great, but according to Vanity Fair, in 2004, a third of the island's male population were convicted of a total of 33 different offenses that stemmed from a long-held practice of "breaking in" pre-teen girls.

The first sexual assault that had been considered for part in the trial had happened in 1964, but investigations suggest that the island's "secret sex culture" and "child abuse on a grand scale" had been a part of life on Pitcairn from the very earliest days — starting with mutineer Fletcher Christian and his offspring. It was a Christian that kicked off the whole thing in 1996, in fact, when 20-year-old Shawn Christian was accused of the sexual assault of a pre-teen girl.

That case was dropped, but the spotlight was on Pitcairn. Convictions were ultimately handed down, but how many young girls suffered in silence for more than a century remains a mystery that can be summed up by this comment from one Pitcairn man talking about offering to prep an 11-year-old for her boyfriend: "It seems the way it's been going down through the times. That was back then. I see times are changing now... and obviously what we did then is not normal."

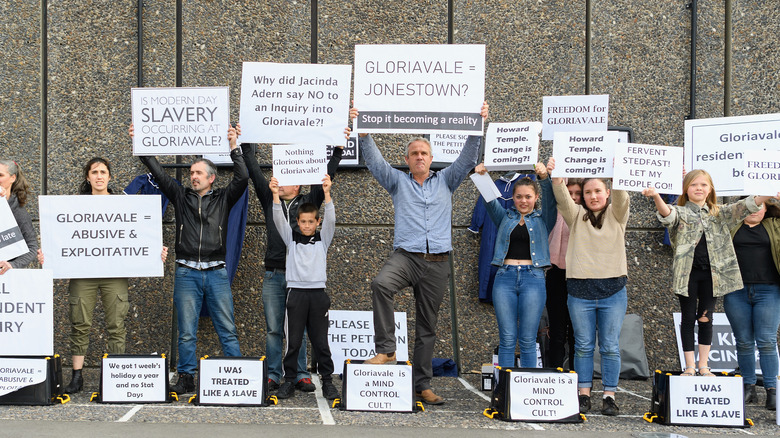

What's going on behind the closed doors of Gloriavale?

Gloriavale is a group founded in 1969 by a man born Neville Cooper, who went by the name Hopeful Christian as he founded his ultra-secretive Cooperite community on the west coast of New Zealand's South Island. In 1994, journalist Melanie Reid went undercover to see just what was going on within its walls. She wrote for Newsroom in 2017, "Going undercover still haunts me." Her undercover foray into the Christian-based community started because she had become friends with one of Cooper's many children to have left — and who struggled to fit into the "outside world." Michael had left Gloriavale when he was 16, and completed suicide even as his father was going to a very public trial for assault.

Telling Hopeful Christian she was an agricultural student looking for real-world experience, she was allowed entry into the community — where she was immediately tasked with "women's work." In just eight days, she said, "I almost felt indoctrinated myself," and says that while there was a lot of "sweetness and goodness," those who have left — like Lilia Tarawa, Cooper's granddaughter — have said (via The Guardian) the community is filled with sexual assault, physical abuse justified by the idea of "spare the rod and spoil the child," and pressure to bear as many children as possible.

In May 2021, law enforcement announced (via RNZ) that investigations into the New Zealand community of Gloriavale were going to "conclude, but 'further enquiries to come.'"

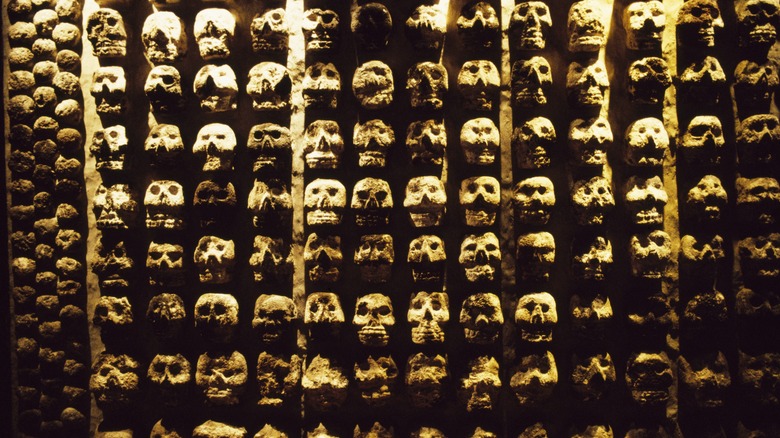

The true scale of Aztec sacrifice

The Aztec city of Tenochtitlan was built on an island in Lake Texcoco, says LiveScience, and Science says that after the city was razed and massive structures like the Templo Mayor were demolished, the Spanish built the beginning of Mexico City on the ruins. But the island of Tenochtitlan is still buried there.

Most of what historians know about the Aztecs came from the Europeans who witnessed the city in its heyday — and there's a lot of talk about human sacrifice and ritual cannibalism. Included in those writings were descriptions of the Templo Mayor — where the sacrifices were held — and the tzompantli, which was essentially a giant rack built to hold the skulls of the victims. Estimates suggest it was big enough to hold 130,000 skulls, but that's long been written off as an exaggeration of a group of conquerors trying to imply that wiping out a whole civilization wasn't that bad.

There were serious doubts about whether it had even existed, but in 2015, archaeologists found it. Researchers from the National Institute of Anthropology and History have confirmed that yes, the rack existed, and yes, it held thousands of skulls. It remains unclear just who the sacrifices were, what their days before their final, really bad day was like, and just what the purpose of large-scale sacrifices were. The island that once supported one of the largest cities in North America might not be an island anymore, but it — and the artifacts — are still there, and still might surrender some pretty dark secrets.