The Messed Up History Of Stanford University

Stanford University is one of the most prestigious universities in the world. If you want to work in the Silicon Valley tech industry, attending Stanford is a sure bet to improve your chances. But Stanford's history is dubious, at best. The school, for example, was founded by a man who made his money off the backs of immigrant laborers and through ruthless business dealings.

Known as one of the infamous "robber barons" of the mid-19th century's industrial revolution, Leland Stanford Sr.'s past isn't the only problematic factor in the university's history. From free speech controversies to offensive mascots and statues, the people who manage Stanford University have had to deal with the bad, the worse, and the ugly facts that have spawned from America's prejudiced past. Did we mention that there were multiple student murders on campus in the 1970s?

Without the Stanfords, there would be no Stanford University. One could argue there might not even be a Silicon Valley. Either way, here's the university's messed up history.

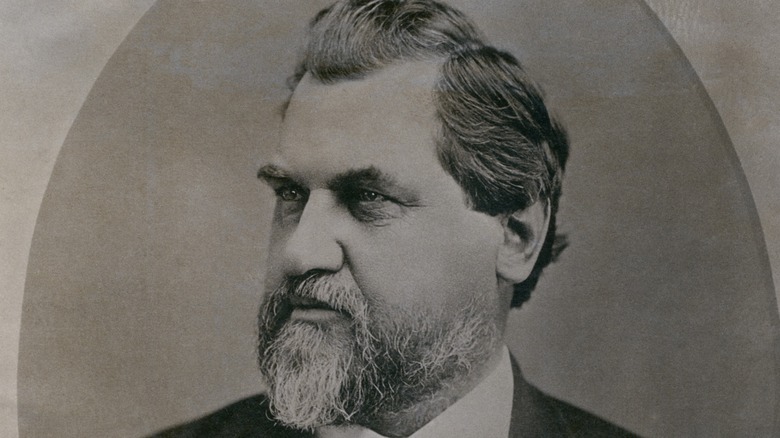

Leland Stanford's problematic relationship with Chinese laborers

Leland Stanford remains one of the most influential people in American history, who drove the Transcontinental Railroad project to success and was one of the first major capitalist players in the U.S. business industry.

But how former California governor Stanford rose to the top is problematic. As someone as staunchly against immigration as he was, it's quite ironic that Chinese immigrants built the railroad that made him his fortune, which ultimately allowed him to found one of the world's most recognized college institutions.

The first wave of Chinese immigration spurred from the California Gold Rush in the late 1840s. According to Workers.org, Leland Stanford "despised Chinese labor, but he hired thousands of Chinese workers when construction of the Central Pacific line" began in 1863. Over 13,000 Chinese workers, which made up of nearly 90% of the Central line's labor, slaved away on the railroad without "any power equipment" and were treated abysmally in both extreme heat and extreme winter conditions. Without their work, America's dreams of connecting its East and West Coasts would have never been realized.

Yet, staunch anti-immigrant Stanford exploited their work and built an empire from it, not that he's alone in this aspect. In an interview with Bay Area journalist Roland De Wolk, who wrote a biography on Stanford, Charles Russo points out, "If you think of other people in power today, you might even suggest there is a parallel."

Jane Stanford and the séance that spawned a university

Though Jane Stanford would attempt to deny the fact that she and Leland attended multiple, documented séances in their time within the Stanford mansion in San Francisco, witnesses like medium Maud Lord Drake still attest to the fact that Stanford University was established through a supernatural revelation in 1891. According to Stanford Magazine, Drake claims that she had been "the guiding intermediary" in Jane and Leland Stanford's decision.

The Stanfords even attended a séance in New York with Ulysses S. Grant and his wife. They weren't alone. Séances and mediums to guide mortals into the spiritual realm were all the rage in the late 1890s thanks to an evangelical revolution now referred to as the Second Great Awakening.

Woman of the spirit world or no, Mrs. Stanford was full of contradictions. It's a tad ironic that Jane was against women attending her own university. What's even more ironic is that in 2020, the university decided to change the name of Serra Mall to Jane Stanford Way, despite the fact that she went to great lengths to prevent women from enrolling there, according to Charles Russo of The Six Fifty.

The mysterious murder of Jane Stanford

Jane Stanford was murdered in 1905, and the culprit or culprits have yet to be revealed to this day. She'd survived an earlier attempted poisoning at her home in San Francisco, and much gossip ensued about her swift departure from her Nob Hill mansion to Hawaii. Some would attempt to hide the reasoning behind her escape. "Mrs. Stanford was threatened with pneumonia and her physician advised a warmer climate than San Francisco," Stanford University's president at the time, Dr. David Starr Jordan, said in a statement to reporters.

Mrs. Stanford had been living as a widow for 12 years after Leland's death. She lived with only "a few trusted servants," according to the San Francisco Gate. On the evening of January 14, she retired to her bedroom. At around 9 p.m., she reportedly began calling for help. "Come and see what is the matter with the Poland water!" Mrs. Stanford said. "I drank some, and it nearly choked me. It burned me so that I ran my fingers down my throat and threw it all up."

Her maid, Elizabeth Richmond, also tried the water and confirmed its strange, bitter taste. The water was tested at a drug store in the morning, and it was concluded that the water had been poisoned with strychnine.

Unfortunately, when Jane disappeared to Honolulu, the culprits' next attempt was successful. While staying at the Moana Hotel in February, she experienced violent body spasms before dying. Honolulu officers reportedly confirmed that cause of death was poisoning.

Stanford University's first free speech controversy

Jane Stanford was put to the test in the spring of 1900 when the head of Stanford's economics department, Edward A. Ross, made a racially charged speech off-campus. According to The Stanford Daily, his claims that America's standard of living would go down, and its citizens may even suffer a drought, due to Chinese immigrants was controversial enough at the time for Mrs. Stanford to pressure Ross into resigning.

Stanford's then-president, a known eugenicist, supported Ross, along with many other professors who resigned in protest of his departure. Ross himself ultimately resigned and expressed his discontent, blaming "elites" who stifle free speech, further claiming that he had been specifically targeted by "high-status Californians." This situation is a direct parallel to debates happening today concerning free speech on America's most prestigious campuses.

Students expressed their discontent with what Jane Stanford was attempting as well. "We sincerely deplore the forces which have resulted in your resignation," the students wrote to Ross. "And we further take this opportunity of expressing to you our administration for the dignified attitude which you, and those of the faculty who have resigned with you, have maintained throughout the present crisis."

David Starr Jordan's problematic viewpoints

The man who backed Edward A. Ross' comments was Stanford's first president, David Starr Jordan, who served from 1891 until 1913.

Jordan was just 40 years old when he took the position. He was also one of America's first leading voices on the topic of eugenics and became a proponent and champion of forced sterilization practices, an inconvenient truth about the founding principles of the university. According to a Stanford website, Jordan "had not only handled the problems of starting a new university but ... handled a major catastrophe [the 1906 earthquake] that had left his university in ruins." What isn't mentioned on the website, however, is his controversial beliefs on race, ethnicity, and population control by sterilization. Jordan's beliefs spawned from Darwin's "survival of the fittest" theory from 1859's "Origin of the Species," according to Lars Johnsson, writing for Palo Alto Online.

A eugenics movement began in England shortly after Darwin's book release. The movement was an attempt to promote "the fittest members of society" to be "selectively married off and reproduce, so that poor heredity would disappear over time," according to Johnsson. Jordan is known for chairing the first U.S. eugenics organization in 1906 and was responsible for the forced sterilization law enacted in Indiana in 1907.

A middle school in Palo Alto was named after Jordan, and in 2018, the Palo Alto Unified School District Board decided to change it to name the school after Frank Greene, Jr. a founding African-American tech entrepreneur.

Free speech concerns, continued

More concerns over free speech at Stanford would soon be raised.

In 1927, local American Civil Liberties Union chairman Harry Ward visited Stanford's campus to criticize its practices of "smothering speech." Leftist students on campus formed the Walrus Club, named after a character in "Alice in Wonderland." "Until there is love of free speech among university faculties and people in authority, we shall have repression," Ward said, according to The Stanford Daily.

Together, the club openly discussed politics, labor rights, and social issues. They brought controversial thought leaders on campus to give speeches, including communist suffragist Anita Whitney, as well as socialist politician Harry Laidler. The speeches and rebuttals that followed would prove immensely popular, with "crowds of students spilling into the aisles."

The free speech movement was revived yet again in the 1960s, fueled by the popular university on the other side of the Bay, Berkley. According to a former leader of Stanford's Students for a Democratic Society, Lenny Siegel, Stanford was attempting to control who was allowed to speak on campus by controlling permits.

The Hoover Institute controversy

The Hoover Institute, which is part of Stanford University's campus and known as a national policy think tank, is actually governed by a different structure than individual schools within Stanford.

Students have protested the institute on numerous occasions as part of various antiwar movements. Stanford provost Persis Drell remembers the scene in the early 1970s well. "When I was a kid growing up on campus, my memory of Hoover in 1971 or 1972 is that there were no windows in the buildings. They were all covered with plywood because the student demonstrators at the time would throw rocks through windows."

There have been many demonstrations and incendiary protests outside the building, including in 1969 and in 2003. In 2018, more controversy surrounded the building when leaked emails by senior fellow Niall Ferguson were revealed. Apparently, Ferguson was encouraging undergraduate conservatives to "conduct 'opposition research'" against liberal students, according to Stanford Politics.

Tense conversations between the Hoover Institution and the University have been ongoing since 2019, and its future status on campus remains uncertain.

Junipero Serra statue removal

Many historical statues and names of buildings around the country have been called into question these past few years, sparking spirited debate and protests about whether they should still stand.

Stanford's recognition of Junipero Serra, an 18th-century Spanish-born Franciscan friar, is highly controversial due to Serra's past with the indigenous community. Two of Stanford's dorms, an academic building, a street in the Main Quad (Serra Mall), the university's official address, and a significant campus road are all named after Serra, according to Los Angeles Times reporting.

Activists on campus, most notably Native American students, pressured Stanford to "erase from the campus all traces of the padre." The activists cite Serra's brutalization of indigenous people at the missions, as well as forcing the them into converting to Catholicism and attempting to erase their culture. It doesn't help that Leland Stanford himself was involved in the Mission Revival movement in the late 1880s.

A committee was formed, and though a decision took a few years, Serra Mall was renamed in November 2019 to Jane Stanford Way.

Meanwhile, a statue of Serra was toppled in downtown Los Angeles in the summer of 2020, continuing a trend around the state of California. According to Newsweek, statues and monuments dedicated to Serra around the state have been getting "vandalized for years, especially since he was made a saint in 2015."

The murder of Arlis Perry

In 1974, the corpse of 19-year-old Arlis Perry was found dead inside Stanford's Memorial Church, "violated with a candlestick," according to The Stanford Daily. Stanford Police investigated whether the murder may have been related to several others on campus within only a year and a half.

Stanford police officer Steve Crawford entered Memorial Church the next morning and found an unlocked door, as well as Arlis' half-nude body near the altar of the church. She had just recently married fellow student, pre-med sophomore Bruce Perry. He was seen as a prime suspect at first but was quickly ruled out. Arlis' murder was officially dubbed a sex crime, but there wasn't enough evidence to distinctively link her death with recent, allegedly cult-oriented murders that had occurred on campus. The case remained cold until 2018, when new evidence came to light.

Crawford had always been a suspect in Arlis' murder as well, but not enough DNA evidence had been identified to convict him. In 2018, he killed himself as detectives entered his San Jose home. He was 72 years old. Santa Clara County Sheriff Laurie Smith considered the case closed after the incident. "We followed all the leads and unraveled the entanglement of the elements associated with the. murder of Arlis Perry," she said. "This is a case that eludes us no longer."

On-campus murders linked to cults

Between 1969 and 1982, seven murders occurred on Stanford's campus.

At the time of Arlis Perry's murder, other recent cases were being linked to a satanic, racially motivated group called the Death Angels. A group called the Process Church had also been suspected, particularly in Perry's case. Police also explored the possibility that the killings could have been linked to the racially motivated Zebra Murders that were terrorizing San Francisco at the time.

Quite recently, one of these cold cases, the murder of student David S. Levine, is back in the news. In 1973, the 20-year-old Stanford junior was stabbed 15 times with a long blade, according to The Stanford Daily. His body was found outside Meyer Undergraduate Library in what the police described as a "swift and vicious attack."

The link to the Zebra Murders was based on the randomness of Levine's murder, as well as a witness claiming to "have seen black men in the area near the time he was killed," according to reporting from The Mercury News. His is one in a string of similar murders that went unsolved for decades. Recent DNA evidence has allowed police to solve three of the murder cases, but Levine's continues to remain a mystery. According to the District Attorney's office, there is no reason to believe that Levine's murder was linked to the others.

Stanford's offensive mascot

A controversial Native American mascot served as the Stanford athletic program's symbol from 1930 to 1970, when Native American students petitioned for its removal and permanent discontinuance. The mascot's big nose was particularly jarring and insulting.

According to The Stanford Daily, "55 Native American students and staff at Stanford presented a petition to the University Ombudsperson, who in turn, president it to [then] President Lyman." Even after the mascot change, there were campaigns to reinstate it or even to bring it back as a more "noble" image of a Native American. In 1975, the conversation was officially over, and the Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU) voted to never make the school's mascot a Native American again in any form.

According to Stanford's Native American Cultural Center, in 1971, directly following the mascot's removal, the Stanford American Indian Organization hosted the First Stanford Powwow to "offset the negative image of the Indian mascot and to bring a diverse Native American presence to the campus."

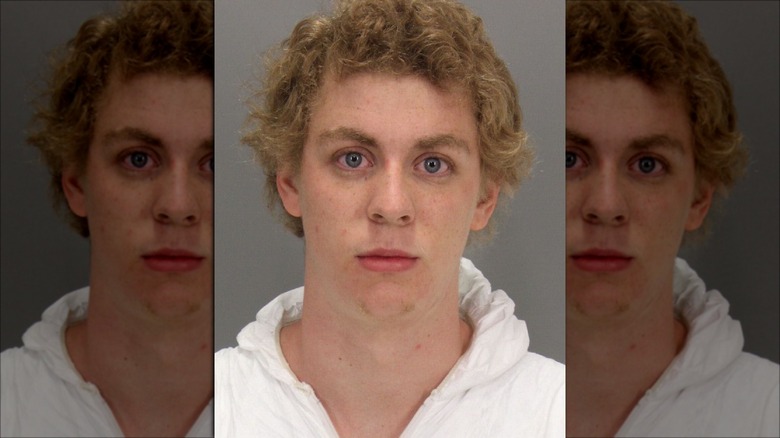

The Brock Turner scandal

The most recent Stanford scandal may ring a bell. In 2016, student swimmer Brock Turner was accused of the sexual assault of Chanel Miller behind a dumpster at a fraternity house while she was unconscious. Two fellow male students found Miller while the assault was happening and came to Miller's aid, staving Turner off.

Public outrage ensued when Turner only served three months in jail, and it spurred protests in California, leading to the removal of the judge on the case. The defendant's father complained, according to New York Times reporting, that "his son's life had been ruined for '20 minutes of action,'" which led to more outrage.

Miller went unnamed for a time until she decided to reveal herself and speak out against sexual assault. She released a memoir entitled "Know My Name" in 2019. "In newspapers, my name was 'unconscious, intoxicated woman.' Ten syllables and nothing more than that," she wrote. "I had to force myself to relearn my real name, my identity."

Turner was convicted and ultimately released on September 2, 2016. He is now living in his hometown of Oakwood, Ohio, where he is registered as a sex offender, according to ABC News.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).