The Most Bizarre Weapons Used By Soldiers In War

Technological innovation has often been spurred by warfare. The need to gain a technological upper hand over opponents has led various powers throughout history to create wondrous inventions that eventually had civilian applications in peacetime as well. There were also more bizarre experiments with mixed results.

A few of the stranger weapons to have been used in warfare were not strange because of any particular oddity but because they were so simple yet deadly in the hands of a skilled soldier. Others were works of true genius, concocted by outnumbered and outgunned defenders to ward off much more powerful enemies despite their material disadvantages. And of course, some weapons from wars past were embarrassingly useless, putting their users at greater risk than the enemies they were intended for. Below is a sampling of some of these weird weapons from throughout history, from the simple and unexpected to the downright bizarre and useless.

The chain mail mask

By World War I, chain mail's heyday had long passed. This archaic armor was naturally no match for machine guns, tanks, bombs, and rifles. Yet it found its unexpected last hurrah in the trenches among British tank crews.

During World War I, the tank was introduced to the battlefield. These heavily armored vehicles rolled through enemy lines and cleared out areas in conjunction with an infantry advance. Their heavy exterior armor protected them and made them difficult to destroy. However, they weren't invulnerable. Drivers still faced the repeated impact of machine gun fire, shells, and grenades in their poorly ventilated compartments.

As shells and bullets repeatedly pounded the tank's exterior, the crew suffered flurries of hot metal shrapnel that could burn their faces. Per the BBC, the British improvised a special mask to protect their tank crews. This mask protected the eyes and left slits for visibility. The lower half of the mask, however, was chain mail. The chain mail was meant to capture shrapnel in its rings and protect the mouth and chin of the tank crewman. The device seems ingenious, although it is unclear how well it worked. Nevertheless, the "medieval" relic of the First World War is truly one of the more bizarre contraptions ever implemented on the battlefield.

The lasso

The lasso, a simple piece of rope with a loop at the end, brings up nostalgic images of the Old West. In the ancient world, however, it doubled as a cheap and deadly weapon. While not necessarily bizarre, the simplicity of the weapon makes it a worthy inclusion.

On the Eurasian steppe, metal was scarce. The nomadic inhabitants relied on armor and weapons made from a mix of wood, hide, and horn. Metal weapons were more frequently found among the aristocracies of steppe societies, so common warriors had to make do with armament such as bows. Others preferred the lasso.

The Greek travel writer Pausanias noted that among the steppe people, the Iranian Sarmatians were masters with the lasso. A favorite tactic of these master riders was to charge an opponent and lasso him off his horse. The Sarmatian warrior would then drag his opponent back to his lines, assuming he survived the initial fall.

Lassoes appear throughout the Iranian-speaking steppe world and were immortalized in Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi's Iranian epic "The Shahnameh." The legendary warrior Rostam, protagonist of the first half of the poem, uses the lasso as his main weapon to successfully defeat his opponent, the Khagan of Chin, by lassoing him and pulling him off his horse.

The man catcher

Although medieval warfare was bloody, the goal was not always to kill enemies. When it came to higher-ranking foes, it was sometimes lucrative to capture them. Ransoms in the Middle Ages could fetch large sums of bullion. However, capturing an enemy was not always easy. To solve this problem, someone devised a terrifying-looking weapon called the man catcher.

Per the Rijksmuseum, the man catcher looked strange indeed. It consisted of a metal pole with a claw of sorts at the end. The tips were spiked, allowing it to dig into an armored enemy enough to immobilize him but not excessively harm him. If used correctly, the wielder could snatch a foe off his horse and, like with the lasso, drag him back for ransom. That was assuming he survived being dragged along the ground!

Although the weapon disappeared from battlefields as gunpowder took over, evidence suggests law enforcement kept using it in Europe to capture criminals without killing them. Versions of it are still used today for riot control and non-lethal restraint. In Japan, two teachers successfully used a two-pronged man-catcher to restrain a crazed knife-wielding man who attempted a stabbing spree in a school. In India and Nepal, a similar version was used to make socially distant arrests in 2020. Instead of cuffing suspects in violation of local lockdown mandates, Indian and Nepali police would restrain them with man catchers. According to NPR, it earned the nickname "social distancing clamp" for its use during the COVID crisis.

Weaponized arthropods

The ancient world experimented with flammable liquids that could be flung at enemies, but sometimes, nothing was more effective than an arthropod. These spineless organisms could not possibly be as effective as a pot of Greek fire, right? Yet multiple civilizations used them to devastating effect. Two famous examples are scorpions and hornets.

King Barsamia ruled the city-state of Hatra in what is now Northern Iraq. In A.D. 198, according to Adrienne Mayor in "Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, and Scorpion Bombs," Roman emperor Septimus Severus besieged the city. Despite the Roman army's skill and reputation, Hatra's defenders repelled the Romans by flinging scorpion-filled pots into the Roman siege lines or breaking them over infantry at the walls. Herodian of Antioch noted that the Hatrans aimed for faces, and many Roman soldiers were stung in the eyes and died painful deaths at the city walls.

In the New World, the Mayan epic "Popol Vuh" records similar tactics, although these are less understood. The Classical Maya appear to have used hornets against their enemies. It is unclear how they worked, but it has been speculated that they threw nests of the insects at their opponents. How the handler protected himself from getting stung, however, is a mystery.

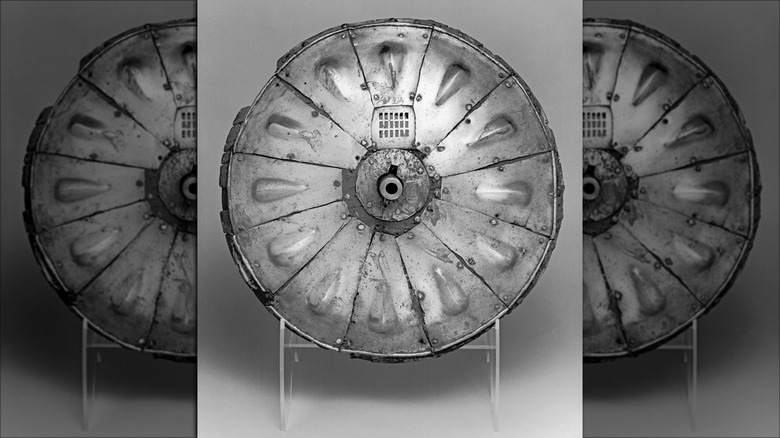

The gun shield

In 1544, English king Henry VIII received an offer from an Italian named Giovanni Battista di Ravenna. According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, this man proposed that Henry arm his gunners with gun shields. Now, the idea behind this strange weapon made sense. However, its execution was lacking.

Henry gave permission to have his bodyguard experiment with the weapon before trying it out on the battlefield. The idea was to place a shield with a hole in it, through which the firearm could be inserted. This way, the gunner would be protected from enemy fire while still being able to see and shoot his enemies through a grill in the shield at eye level.

Although Battista's idea theoretically was well-thought out, there was one major problem. As detailed by the Walters Art Museum, the shield was too heavy and made it impossible for the gunner to fire his weapon. The only way to fire the gun was to place the shield on a stand or some other support. Thus, it was easier to fire the gun unprotected without the shield. The idea was abandoned for infantrymen, although it was possibly repurposed to be used on ships, where gunners could use the deck for support.

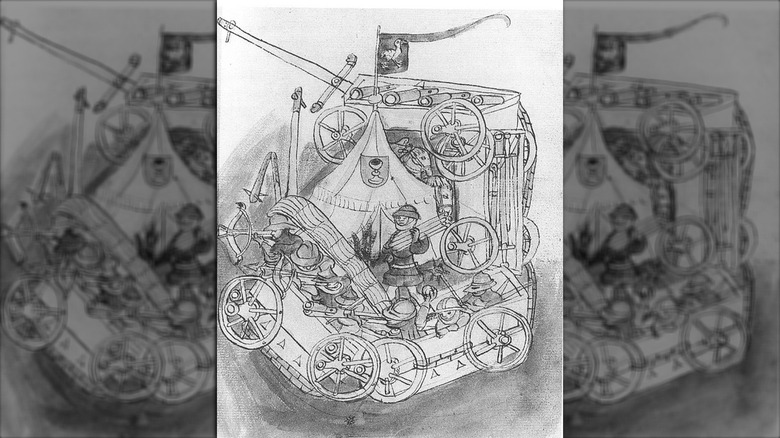

The Hussite Wagenberg

During the 15th century, a firebrand preacher named Jan Hus inveighed against the Roman Catholic Church. After his execution for heresy in 1415, his followers, known in English as Hussites, spread throughout the modern Czech Republic and rose in revolt against the Holy Roman Empire in 1419. According to Medievalists, from 1419 to 1436, crusaders and Hussites fought across Bohemia. Although the Hussites were outnumbered and underequipped, they devised an ingenious weapon to negate the Imperial army's most powerful arm — its knights.

Wagons had been used in war since ancient times, usually as wagon forts. So, although the Hussite use of wagons was not new, their bizarre-looking modifications made them virtually impregnable. According to Penn State, under the old commander of the Bohemian royal guard, Jan Zizka, the Hussites developed the wagenberg. Zizka reinforced the wagons with wood panels on all sides, and each wagon became a mobile fort filled with gunners, slingers, crossbow men, and pikemen.

The Hussite wagon fort was devastatingly effective, defeating five crusader armies. When imperial knights charged the fort, which was usually positioned on high ground, missile fire and pikemen would cut them down. In an offensive capacity, these rolling fortresses were mobile archery and gunnery platforms that were driven through enemy lines.

The tactic was so successful that it spread to Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and eventually all the way to India. Eventually, heavier, more powerful field artillery would negate the advantage of the war wagon, but in the 15th century, this simple yet ingenious weapon ruled the battlefields of Eastern Europe.

Dead bodies

A dead man cannot fight. In the Middle Ages, though, dead soldiers sometimes proved more useful than living ones. It was generally understood that plague could spread from person to person, even if the causes were not yet fully understood, and in 1346, the inhabitants of the Genoese city of Caffa discovered to their horror how an infected man could fight even in death.

Per the CDC, the 14th-century Crimean port of Caffa (now Feodosia) was a bustling merchant city. However, the city's Catholic majority often clashed with its Muslim neighbors, who were subject to the Mongol Golden Horde. After one dispute degenerated into violence, the Golden Horde laid siege to the city in 1346.

With naval dominance in the Black Sea, Genoa could reinforce and resupply the city by sea. Meanwhile, the Black Death had spread via the Silk Road into Southern Russia. According to Genoese chronicler Giovanni de Mussi, the pestilence struck the besiegers, killing many and forcing them to abandon the siege.

Before leaving, the furious Mongol commander sent the defenders one last grisly souvenir. As the Tatars dismantled the siege lines, they loaded dead bodies of their own men onto catapults and flung them over the walls. Many of Caffa's inhabitants fled the city, hoping to escape the plague, but in doing so, they inadvertently brought it first to Constantinople and Anatolia and then eventually to Italy itself. This unconventional warfare on the Mongols' part accelerated the spread of the plague, which ravaged Caffa and killed over 25% of Europe's population, a fitting Mongol revenge.

Aztec macuahuitl

According to the University of Houston, the Aztec Empire of Mexico lacked the metal smelting technologies that had been around in Europe for nearly three millennia. To compensate in the field of weaponry, they employed the black volcanic glass obsidian, which they used to produce blades. This led to the production of a bizarre-looking weapon that can be best described as a combination of a saw, a sword, and a club.

The macuahuitl, as it was called in Nahuatl, could be used to deadly effect. It could be swung as a sword to slash an opponent with sharp obsidian blades placed in grooves between the wood. It would be used as a club to inflict blunt force trauma on an enemy, knocking him unconscious so he could be sacrificed and captured. It could finally be used as a saw. When hacking through an opponent, pulling the club back created a sawing effect that could amputate limbs. This final function intimidated the Spanish conquerors of Mexico and gave the weapon its fierce reputation.

Spanish chronicles of the Conquest of Mexico give a terrifying account of the Aztec club. When Spain invaded the Aztec Empire, they brought horses, an animal unknown to the New World. Despite their initial fears, Aztec warriors found that the macuahuitl was brutally effective against cavalry. Bernal Diaz del Castillo and several other Spanish conquistadors that fought in Mexico described how the club could shatter a horse's chest, bleed one to death with many cuts, or in one case, even decapitate the animal.

The Finnish Molotov Cocktail

Following the conquest of Eastern Poland in 1939, the Soviet Union attacked Finland. The Finnish army fought back in a brutal conflict called the Winter War as a country of 4 million people fought to preserve its liberty against communism. The Finns, despite being outnumbered and outgunned, would not be easily bowed.

The Finns' main problem was the lack of anti-tank guns. To compensate, they transformed crude Spanish petrol bombs into a sort of sticky grenade dubbed the "Finnish Molotov Cocktail" by Jaeger Platoon. Because petrol bombs often endangered the thrower as well as the target, the Finnish army completely revamped the weapon. The bottle was filled with a mix of tar, kerosene, and potassium chlorate, making a sticky, highly flammable mixture. The bottle was then sealed tightly to prevent leakage. Ingeniously, they were lit with two matches on the sides. A soldier could safely light the matches and throw the bottle, ensuring that if it broke, it would light up its target.

The Finnish Molotov Cocktail proved effective against Soviet tanks. According to Finland at War, the cocktail could ignite the tank and smoke out the crew, whom Finnish riflemen could pick off at leisure. A bottle in the hatch would burn the crew alive, while a bottle to the treads could immobilize the tank. The tar ensured that the liquid stuck to clothes and skin, making an encounter with a Finnish Molotov Cocktail a guaranteed death sentence for Soviet tank crews.

The German Goliath

While the Finns created the Molotov, the Germans experimented with their own contraptions. In 1942, they pioneered moderately successful remote-controlled mini tanks to fend off Allied tanks and blast through enemy fortifications.

The German mini-tank was called the Goliath, a misnomer considering that the contraption was small enough to slip underneath a full-sized tank — while carrying up to 220 pounds of ordnance, making it useful not only against enemy tanks but also against pillboxes, gun emplacements, and other field fortifications.

According to HistoryNet, the Goliath was the latest in a string of experiments involving remote-controlled explosive delivery systems. It was controlled with a joystick that was hooked to the Goliath with an unwinding cable. This made the Goliath useless if the cable was cut. However, the amount of explosives made it extremely potent if it reached its intended target, and Goliaths were used to devastating effect during the Warsaw Uprising in World War II. Although the Goliath's problems led to its eventual abandonment, its principal contribution was in the field of robotics. British, Israeli, and American scientists all built on the principles behind the Goliath, creating remote-controlled mine-clearing and bomb-disposing vehicles.

Soviet kamikaze dogs

The Soviets hold the title of the least successful anti-tank experiment. Needing to neutralize Germany's legendary Panzer Corps, they tried a highly unorthodox solution, one that was a miserable failure and today would be considered animal abuse.

During Operation Barbarossa, the Soviet commanders created kamikaze dogs. According to the U.S. Government ORDATA Database on explosive munitions, the Soviets strapped the dogs with roughly 26 pounds of TNT inside two pouches carried on the dogs' sides. The Soviets trained these dogs to crawl underneath German Panzers. Once the dog reached the underside of its target, a spring mechanism would pull the pin on the explosives and detonate the dog and the tank.

According to War History Online, the Soviets encountered a major problem with this "weapon." Often, the dogs simply refused to run toward the Germans or, worse, would run toward their own lines and create havoc among the Soviet vehicles. Since the German tanks smelled unfamiliar due to their gas engines, the dogs simply ran to the more familiar Soviet diesel-powered tanks, with which they had trained. The bizarre program was shelved after one year, but the use of animals to ferry explosives did not die. As recently as 2014, Israeli forces shot a suicide donkey bomber near the Rafah border crossing.

The Novgorod

Russia's defeat in the Crimean War exposed the country's technological backwardness, prompting Tsar Alexander III to begin modernizing, among other things, the navy. With the advent of ironclad monitors in the United States and Europe, Russia risked falling behind its global rivals. In response, Russia experimented with a new design — a circular ship.

According to the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame, a Scottish engineer named John Elder had been delving into creating floating fortresses. Russian sailor and engineer Andrei Popov, according to the Center for International Maritime Security, following Elder's lead, decided to make the circular ship a reality.

Popov and Elder noted that a circular ship would displace more water and allow a greater number of guns to be deployed on the vessel's deck. As an added advantage, much of the hull would be underwater, making it difficult to hit from the deck of another ship. In 1873, the Russian navy put the Novgorod to sea.

Unfortunately for Popov, the Novgorod had been approved without testing. Because the ship was so oddly shaped, the rudder and propellers were too small to move it, and the vessel was unstable when unmoored in even calm waters. According to the Russian Black Sea Fleet, the Novgorod was only utilized briefly during the Russo-Turkish War in 1877. It was assigned to coastal defense afterward and eventually scuppered in 1903 as dreadnoughts and other steel steamers came to rule the seas.