The Tragic Life And Death Of Empress Sisi Of Austria

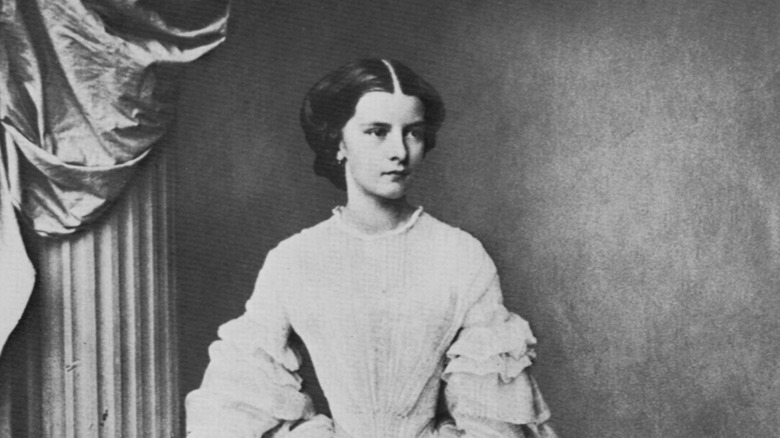

Empress Elisabeth of Austria, who later became queen of Hungary as well, never wanted the position, but she ended up being the longest-serving empress of Austria. Later in her life, she'd say, "One is sold as a child at 15, and one takes an oath one does not understand but can never undo."

Even though Elisabeth, nicknamed "Sisi," was thrust into a position she didn't want, she managed to make her own way through life. She put up with her meddling mother-in-law, she ignored politics unless it was regarding a subject of her interest, and she was able to avoid most of her royal duties by the end of her life. With her adventurous spirit and love of the sea, Elisabeth even had a tattoo of an anchor on her right shoulder.

But despite everything, Elisabeth's life was marked by tragedy, and she spent most of her years struggling with anxiety and disordered eating. And although she was known for her beauty and taking great care in her appearance, "she hated nothing so much as being gawped at." Her aesthetic obsession was for her own eyes only.

In the end, Elisabeth died by an assassin's hand, but she was never really the intended target. As with most things in her life, she just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. This is the tragic life and death of Empress Sisi of Austria.

The early life of Sisi

Empress Sisi was born Elisabeth Amalie Eugenie, Duchess in Bavaria, on December 24, 1837, in Munich, Bavaria. Her parents, Duke Maximilian Joseph and Princess Ludovika of Bavaria, had seven other children, but compared to other aristocratic families, their children's lives were relatively unstructured. ThoughtCo writes that Elisabeth and her brothers and sisters "spent much of their time riding in the Bavarian countryside, rather than in formal lessons."

In "The Reluctant Empress," Brigitte Hamann writes that when Elisabeth was 15 years old, she fell in love with a Count Richard S., whom her mother considered to be "a totally unsuitable man." Unfortunately for Elisabeth, the Count was sent away for a time, and when he was able to return, he died soon after from an illness. "Elisabeth was inconsolable. Her broken heart grew heavier to the point of depression. She locked herself in her room for hours to weep and write poetry."

Elisabeth's maternal aunts married into the Austrian royal family, and the son of Princess Sophie of Bavaria ended up becoming the young Emperor Franz Joseph when his uncle, Ferdinand I, abdicated and his father was persuaded by Sophie to renounce the throne. And upon seeking a bride for Emperor Franz Joseph, Princess Sophie "looked on to the daughters of her sister Maria Ludovika as a welcome pool of possible candidates," according to The World of the Habsburgs.

The arranged marriage

Originally, the arranged marriage was planned between Elisabeth's sister Helene, also known as Néné. But when Emperor Franz Joseph saw Elisabeth during the arranged meeting with Helene in Bad Ischl during the summer of 1853, he fell madly in love. At the time, Emperor Franz Joseph was almost 23, and Elisabeth was about to turn 16 years old.

National Geographic writes that although "efforts were made to steer his attentions to the older sister," Franz Joseph was insistent. According to ThoughtCo, "He insisted to his mother that he would not propose to Helene, only to Elisabeth; if he could not marry her, he swore he would never marry." And so, his mother Sophie decided to go along with the match.

Sisi herself wasn't necessarily opposed to the marriage, writing, "I love the emperor. If only he were not the emperor." But according to "The Reluctant Empress," Elisabeth's family reminded her that "one does not send the Emperor of Austria packing," and the wedding was set. Meanwhile, Sisi was put through a "crash-course" to prepare for being an empress. During their engagement, although Franz Joseph was often "full of joy," Elisabeth was "often found crying."

On April 24, 1854, the two were wed in Vienna in the Church of St. Augustine.

Suddenly an empress

All of a sudden, Elisabeth was thrust into the highest levels of royal life as she became Empress Elisabeth of Austria. Any semblance of privacy was stripped away, and every aspect of her life was now monitored and controlled. According to National Geographic, "the morning after she consummated her marriage, the whole court was informed." There were also incredibly strict rules of etiquette that "frustrated the progressive-minded Sisi," writes ThoughtCo.

In "The Reluctant Empress," Brigitte Hamann writes how Elisabeth ended up battling over basic traditions, such as giving away her shoes after wearing them just once. She also felt uncomfortable being dressed by ladies-in-waiting who were essentially strangers. However, despite being an empress, she did not get her way.

Elisabeth felt homesick in Vienna, especially since her new husband was frequently occupied with being emperor. Meanwhile, her aunt-turned-mother-in-law constantly tried to control both the marriage of Elisabeth and Franz Joseph and the goings-on of the Austrian court, to the point where many considered Sophie to be "the secret empress."

The World of the Habsburgs writes that the first few years of Elisabeth's new life as an empress and a wife were "a traumatic experience" which would ultimately lead her to distance herself from the Viennese court. "She saw herself degraded to the role of a brood mare, expected to produce numerous healthy offspring, male for preference."

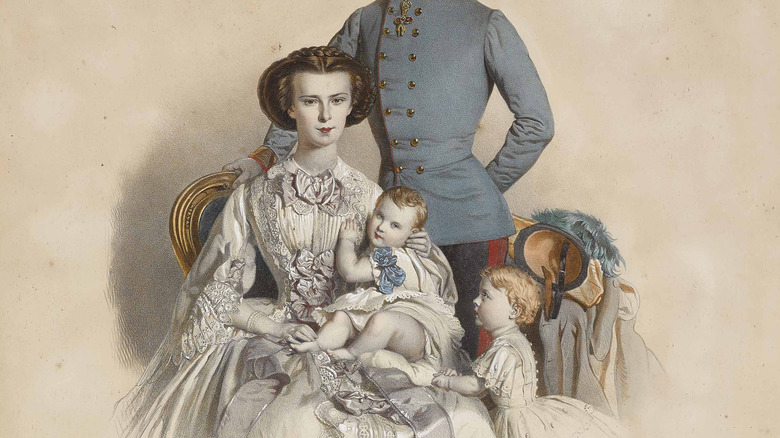

Sisi's daughters

Elisabeth was pressured to produce an heir, and within a year of the wedding, she gave birth to her first child, a daughter, on March 5, 1855. According to National Geographic, not only did Sophie keep Elisabeth from naming her own daughter, insisting instead that the child be named Sophie, after herself, but "she also took charge of the infant's care, declaring that the mother was too young to do it properly herself."

On July 12, 1856, Elisabeth gave birth to her second child, another daughter, whom Sophie also refused to let Elisabeth care for. However, after a couple of weeks, Elisabeth asserted her right to be a mother, and both Sophie and the newly born Gisela were moved to Elisabeth's rooms.

Unfortunately, Elisabeth was repeatedly pressured to produce a son, to the point where a pamphlet was left anonymously in her private chambers with certain passages underlined, according to "The Empress Elizabeth of Austria" by Karl Tschuppik: "The natural destiny of a Queen is to give an heir to the throne ... So soon as they desert this duty, they become the source of all manner of evil ... If the Queen bears no sons, she is merely a foreigner in the State, and a very dangerous foreigner, too." Although it's not known who authored the pamphlet or left it there, many believe that Princess Sophie was responsible.

The death of Sophie

During the spring of 1857, Elisabeth and Franz Joseph took their two daughters on a trip with them to Hungary. Both of the children ended up falling ill, either from dysentery or typhus, and two-year-old Sophie died as a result. National Geographic claims that in her grief-stricken state, Elisabeth "relinquished responsibility for raising Gisela to her mother-in-law." However, Bax of Things states that Elisabeth was held responsible by Princess Sophie for little Sophie's death, and she insisted on taking over "the upbringing of the imperial children."

After Sophie's death, Elisabeth's exhaustion and depression from royal life was exacerbated, and according to The World of the Habsburgs, "She found no support in her husband." It was around this time that Elisabeth began her aesthetic regimens that would in later years turn her into the subject of fascination. In addition to maintaining her ankle-length hair through beauty treatments, she started exercising frequently and her eating became disordered. During this time, Elisabeth also threw herself into learning languages and studying literature.

Sisi finally has a son

On August 21, 1858, Elisabeth finally gave birth to a son, who was crowned Prince Rudolf. According to "Notorious Royal Marriages" by Leslie Carroll, "Franz Joseph was weeping tears of joy as a 101-gun salute announced to the people of Vienna that the Habsburgs had an heir."

As with Sophie and Gisela, Rudolf was taken away from Elisabeth almost immediately. But this time his father, Franz Joseph, was going to dictate his upbringing. The World of the Habsburgs writes that Rudolf put on a military uniform for the first time when he was two years old.

Major-General Count Leopold Gondrecourt was put in charge of raising and educating Rudolf, and "his educational methods bordered on the sadistic." Since Rudolf was deemed to be "overly sensitive" by his father, in addition to intensive military exercises no matter the weather, he would be intentionally startled awake at night by pistol fire. This treatment reportedly drove Rudolf "to the verge of mental and physical breakdown."

This would remain Rudolf's life until 1865, when Elisabeth threatened to leave her husband if Rudolf continued to be subjected to this treatment. Franz Joseph acquiesced, and Elisabeth made sure that afterward, Rudolf received an education "based on liberal middle-class principles."

An unhappy marriage

Elisabeth's marriage with Franz Joseph wasn't an easy one. According to The World of the Habsburgs, after fulfilling the expectations of having a son, Elisabeth "soon fell into a kind of passive resistance."

She also kept suffering from a mysterious illness, which led her to spend a great deal of time away from Vienna to recover. According to ThoughtCo, Elisabeth's illnesses often came up whenever she was in the Viennese court, so it's possible that her physical reactions were psychosomatic responses to anxiety and stress. One of her departures in 1860 was thought to have been "brought on by the rumors of her husband's affair."

But by 1861, Elisabeth started to assert herself more and more successfully. In addition to her later ultimatum regarding Rudolf, she made sure that she had her own bedroom and refused to entertain the idea of another pregnancy. In 1863, Elisabeth also began learning Hungarian, and by 1866, she was following the country's affairs.

Sisi's disordered eating

Elisabeth's anxiety also took on the form of disordered eating, which included a strict diet and hours of exercise every day. Although Elisabeth was almost 5'8," she weighed only around 110 pounds for most of her life. According to author Mimi Matthews, sometimes Elisabeth only ate "pressed extract of raw chicken, partridge, venison and beef." Or, "she would eat nothing but eggs, oranges, and raw milk" for weeks at a time.

She also exercised for hours every day, and in addition to hiking and riding horses daily, Elisabeth "had exercise rooms installed in her apartments ... which was highly unusual for a woman in her elevated circles," writes The World of the Habsburgs. However, in the 1880s, Elisabeth's health problems became so severe that she was forced to give up riding.

Tightlacing was also in fashion during this time, and during Elisabeth's "peak tight-lacing period," her waist measured just 16 inches. Although she stopped tight-lacing by 1862, she continued to be described as "almost inhumanly slender" for most of her life. Some accounts claim that Elisabeth's fatphobia influenced her youngest daughter, Valerie, who reportedly fainted when she first met Queen Victoria.

Elisabeth also was also famous for her long hair, which took her almost three hours a day to take care of. She was also terrified of aging and wrinkles, at times "even wrapping slices of raw veal around her face when she slept."

An affinity for Hungary

Although Elisabeth's visit to Hungary had been marked by tragedy with the death of her daughter, she fell in love with the country and "felt [it] to be her spiritual home." She took an interest in the country's affairs, and this was one of the few times that Elisabeth would get involved in political affairs.

National Geographic writes that Elisabeth "sympathized with the rebellious Hungarian aristocrats" and ended up being directly responsible for keeping Hungary in the empire.

According to Sisi's Road, Hungarian noblewoman Ida von Ferenczy would even become one of Elisabeth's "closest confidants" after they met in November 1864. In January 1866, Elisabeth also met Hungarian diplomat Gyula Andrássy, a former rebel, for the first time, and a close friendship between the two developed alongside Elisabeth's interest in Hungary. By 1867, "thanks to Sisi's intense lobbying, Andrássy negotiated terms with Franz Josef that granted Hungary its own constitution."

ThoughtCo reports that their relationship was so close that there were rumors of an affair, and when Elisabeth's fourth child, Valerie, was born, Andrássy was rumored to be the father. It likely didn't help that Valerie was taught Hungarian as her first language.

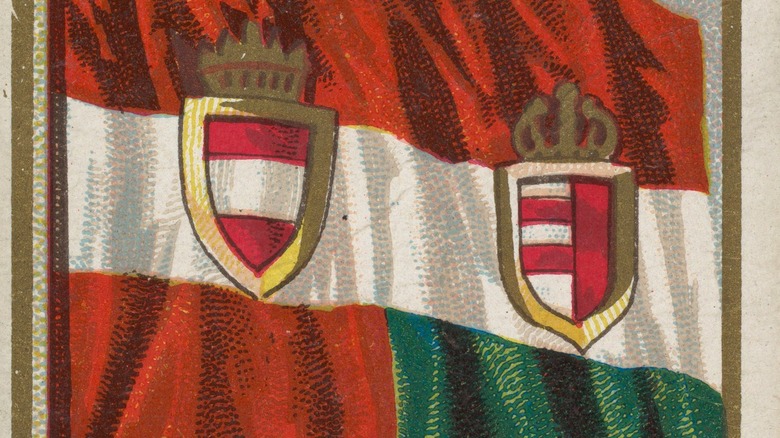

The Austro-Hungarian compromise

After the 1848 Hungarian Revolution, Hungary's constitutional privileges had been stripped away, and the country was essentially ruled under martial law for the next 20 years. But thanks to Elisabeth, in 1867, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise was established, creating the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

According to National Geographic, this meant that Austria and Hungary would have "separate regimes and governments but [be] united under a single crown." As a result, Elisabeth and Franz Joseph were crowned the constitutional monarchs in Hungary on June 8, 1867. Elisabeth ended up spending so much of her time in Hungary that people began to refer to her as "Elizabeth of Hungary."

ThoughtCo writes that being in Hungary gave Elisabeth an additional excuse to stay away from the Viennese court, and even when her mother-in-law died, Elisabeth still chose to stay away. She also "gained a reputation for her preference for 'common' people over mannered aristocrats and courtiers."

The death of Rudolph

Although Elisabeth's son Rudolph tried to succeed in royal life, due to his liberal views, he was often excluded "from any position of influence" by his father and treated as an outsider in the court. His relationship with his mother Elisabeth was comparatively better, but "a certain distance always remained between them."

According to The World of the Habsburgs, Rudolf's marriage with Princess Stéphanie of Belgium was relatively happy at first, and they had one daughter, Elisabeth, also known as Erzsi in the family. However, after Rudolf picked up a venereal disease during one of his affairs and Stephanie was rendered infertile after being infected by him, "the relationship reached its nadir."

Like his mother, Rudolf suffered from bouts of depression. Add to that his frustrations regarding his treatment by his family and the royal court, and he would turn to drinking and drugs. Having considered the idea of suicide before, on January 30, 1889, Rudolf and his 17-year-old mistress, Baroness Mary Vetsera, were found dead in Rudolf's hunting lodge in the village of Mayerling. Known as the Mayerling incident, the death appeared to be a murder-suicide, but the family released a story that Rudolf had died "due to a rupture of an aneurysm of the heart."

After Rudolf's death, Elisabeth disappeared from the Vieneese court almost completely. Instead, she started traveling around Europe and writing "melancholic poems." While traveling, she often used pseudonyms, such as the "Countess of Hohenembs," and hid her face in pictures.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

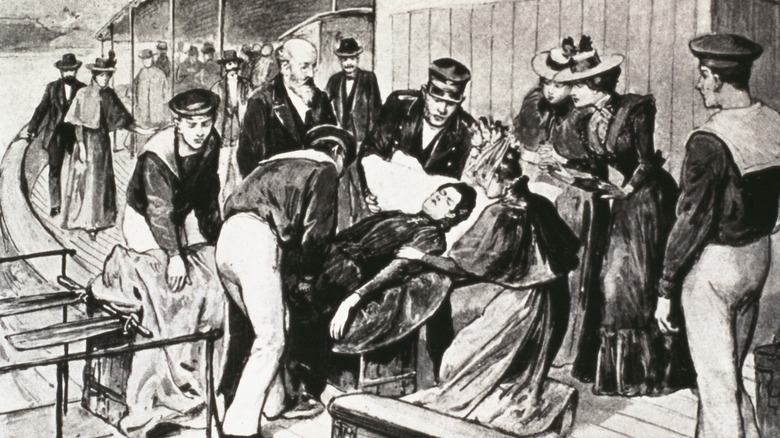

Sisi's assassination

In 1898, Elisabeth was in Geneva, Switzerland, for a health cure, and word got out that she was there. And despite rumors of possible assassination attempts, on September 10, Elisabeth decided to walk with Countess Irma Sztáray from the hotel to the pier to board a steamer without any bodyguards.

According to the Sisi Museum, Luigi Lucheni, an Italian anarchist, was already in town with a plan to assassinate someone "as a protest against the plutocracy." His initial target was Prince Henri Philippe Marie d'Orléans, but after Prince Philippe cancelled his visit and Lucheni read about Elisabeth in the papers, he made her his target.

As Elisabeth was on her way to the pier, Lucheni attacked her, stabbing her once in the heart with a sharpened file. Although Elisabeth fell down from the blow, she got up quickly and managed to board the ship. However, once they were aboard the steamer, Elisabeth collapsed. Upon undoing her top, Sztáray noticed the bloodstain and realized that Elisabeth had been stabbed.

The boat turned around, and Elisabeth was quickly taken back to the hotel, but she soon died of internal bleeding. History of Royal Women writes that "blood had trickled so slowly into the pericardium that the heart had stopped gradually."

What happened to the assassin?

Luigi Lucheni made no attempts to mask his crime and was arrested at the scene. He'd always planned to "murder the first high-born person" that he encountered in Geneva, and Elisabeth just happened to end up in his path.

According to SWI, Lucheini showed no remorse, and after a daylong trial, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. However, he'd wanted to become a martyr for his cause and was upset when he realized that the death penalty wasn't an option because Geneva had abolished capital punishment in 1871. As he was taken away, Lucheini shouted, "Long live anarchy! Down with the aristocrats!"

While in prison, he wrote a memoir, "a shattering testimony to the life of the poor in Europe in the late 19th century," but in 1909, the memoir disappeared "in mysterious circumstances." And on October 19, 1910, Lucheni was found hanged to death in his cell. According to the Chicago Tribune, Lucheni's head was later severed from his body and preserved in a jar of formaldehyde, in an attempt to understand the "criminal mind."