How Historic Pandemics Changed The Course Of History

Despite the fact that it's persisted more or less continuously for thousands of years, society is somewhat delicate. Civilization, after all, is really just a network of casual agreements to abide by certain rules, like not crossing invisible, made-up borders or not gathering your neighbor's livestock and taking them home with you when you're hungry.

So it shouldn't be a surprise that any sense of permanence or stability in society is purely superficial — things are constantly changing in response to even the slightest pressure. And when that pressure rises to the global level with events that affect a widespread area all at once, the changes that happen in response can be dramatic.

As everyone knows all too well today, pandemics are global crises that have enormous short- and long-term consequences. You might think that once the crisis is over that everything will go back to the way it was, but history suggests that there will probably be measurable differences in society going forward. To get some idea of what might happen, here's how historic pandemics changed the course of history.

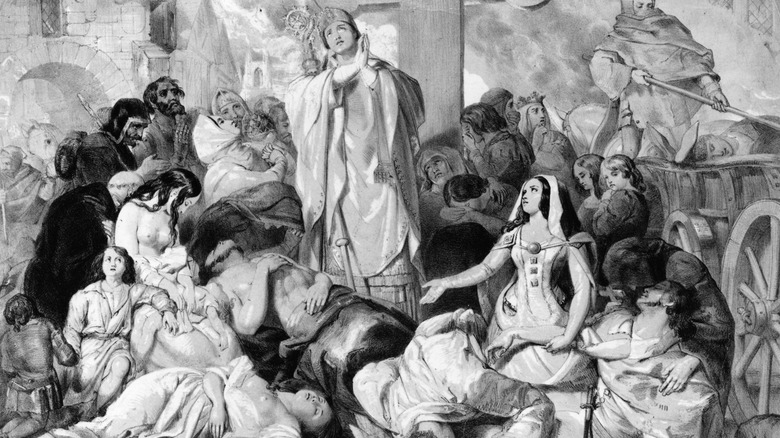

The Black Death: ended feudalism and Viking raids

The Black Death (the bubonic plague) remains the deadliest pandemic in history. Beginning in Asia and spread by the Mongol armies, it arrived in Europe in the middle of the 14th century and killed somewhere between 30 and 50% of the European population, according to American Scientist. Somewhere between 75 to 200 million people died in just a few years.

So many people died, in fact, that the pandemic changed society completely. As reported by History, the Black Death ended a war between England and France, and it forced the Vikings to stop their restless raids and exploration, altering the course of Norse history forever. The shocking loss of available laborers also made the feudal system of the Middle Ages collapse — workers could move about and demand better wages, and fewer mouths to feed meant there was suddenly plenty of food. These factors increased social mobility and lay the foundations of modern society.

The Black Death also broke the power of the Catholic Church. As New York Magazine notes, the huge death rate pushed people into mysticism and sowed the seeds of doubt about religion. People questioned Catholic doctrine, setting in motion the process that would lead to the Reformation.

The Justinian Plague: ended a united Rome and boosted Christianity

In the 6th century A.D., the Western Roman Empire was no more, but the Eastern Roman Empire — re-branded by historians as the Byzantine Empire — was in ascendance. Emperor Justinian had big plans. As he fought a bitter war against the Sassanid Empire in Persia, he plotted to reclaim the West and reunite the Roman Empire in all its former glory, according to the Institute for the Study of Western Civilization.

But, as History explains, when a plague spread throughout the empire (most likely bubonic plague), Justinian was forced to abandon these plans. He simply lacked the manpower and money to hold onto the West when so many people were dying (National Geographic estimates somewhere between 30 and 50 million people died— about half the entire world's population at the time) and fleeing the cities in the East.

The Justinian Plague established Christianity as the dominant religion in Byzantium and Europe. As explained by Medievalists.net, the incredible level of mortality made people believe the world was ending, and many ran to the Christian Church for comfort and guidance. Christianity rose and the Catholic Church attained its incredible power in part due to the pandemic ravaging the world around it.

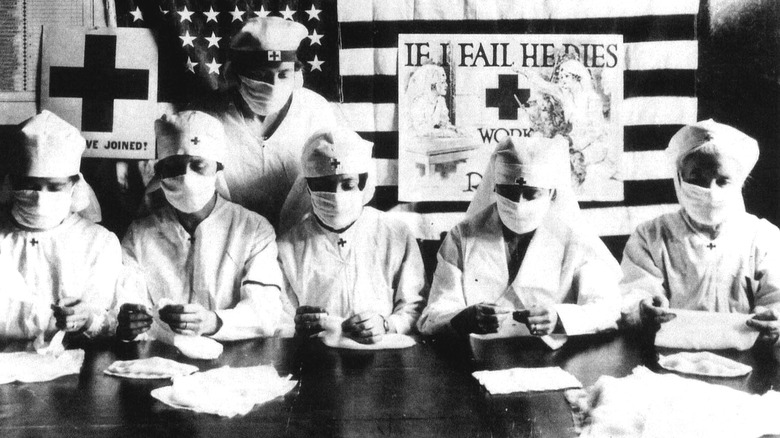

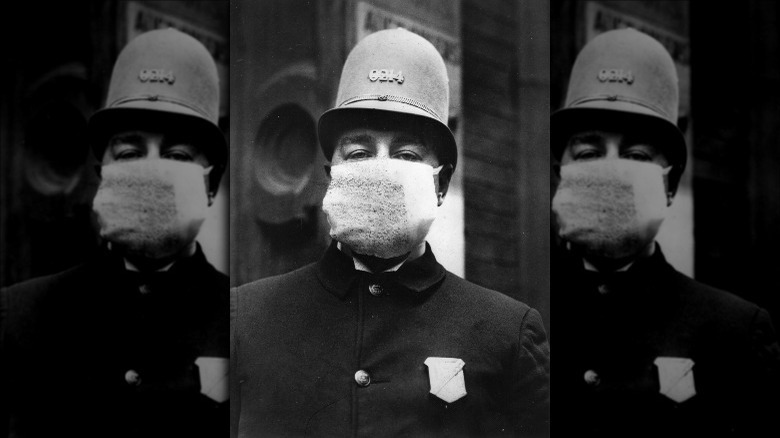

The 1918 flu: the first modern pandemic

The 1918 H1N1 flu pandemic (sometimes still referred to as the Spanish Flu despite the inaccuracy of that description) was a devastating plague that infected half a billion people and killed somewhere between 50 and 100 million worldwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Business Insider reports that the lethalness of the pandemic was exacerbated by chaos: World War I was winding down, and many areas of the world had reduced health services. At the same time, massive troop movements around the world helped to both spread and obscure the plague's progress.

H1N1 was a shock to the world, which hadn't seen a plague on that level for a very long time. Governments had to invent strategies for prevention and treatment on the fly — but, as Discover Magazine notes, that sense of emergency may have helped end the pandemic and save countless lives, as the media tracked the disease's progress and communities united in their efforts to combat its spread. In fact, the 1918 flu led directly to the creation of he vaccine and mitigation programs we take for granted today.

The Plague of Athens: the fall of a city

The Peloponnesian War stemmed from alliances formed between independent city-states in Ancient Greece, with Athens leading the Athenian League and Sparta part of the Peloponnesian League. Ostensibly these alliances were to help defend Greece from Persian aggression, but in reality they were domestic rivals, and in 431 B.C. war broke out between the two groups.

Sparta's military strength lay in its land army, while Athens had a dominant navy — making any sort of decisive battle difficult. The Spartans invaded and laid Athens under siege, but this might not have been decisive except for one thing: As History explains, a plague that had already passed through northern Africa decimated the Athenians in 430 B.C. Worldhistory.org estimates that the plague killed about one-third of the total population.

As explained by the Atlantic, the plague changed everything. Although the war would drag on for almost another 26 years, the loss of manpower suffered by the Athenians doomed them to defeat, and ultimately doomed the democratic government of the city itself. Many criticized the Athenian government for ignoring the sanitation and health issues that allowed the plague to spread so easily, and as a result democracy lost its luster for centuries to come.

The Antonine Plague: Destabilizing an empire

According to History, the Antonine Plague began somewhere in Asia around 165 A.D., and it was spread by the Huns as they rampaged into Europe. Germanic tribes caught it from the Huns, and in turn spread it to the Roman troops they were more or less continuously fighting.

The plague burned its way through the Roman empire for the next two decades. Smithsonian Magazine explains that it killed so many Romans at every level of society that it utterly changed the makeup of the population. Emperor Marcus Aurelius, known to history as the last of the "Five Good Emperors," was forced to repopulate his devastated armies with slaves and gladiators, and he elevated many commoners and even slaves to the aristocratic ranks just to keep the government going.

In 180 A.D., Marcus Aurelius himself died, probably of the plague. The plague ended the string of strong, capable emperors and elevated Aurelius' son Commodus to the throne. As explained by Britannica, Commodus' reign was disastrous, and many historians believe he helped usher in a period of instability for the Roman Empire commonly referred to as the Crisis of the Third Century, which transformed Rome into a military dictatorship ruled by an emperor who had discarded any semblance of republican legitimacy.

The Cyprian Plague: bringing the Saxons to England

The history of the world is a deep study of the law of unintended consequences. If you need an example, consider the Cyprian Plague. History explains that this plague probably had its origins in Ethiopia around 250 A.D. It quickly spread through Africa into Rome, and then was a bit of a long-haul pandemic, rising and falling in waves over the next few centuries, always spreading a little further with each recurrence.

By the middle of the 5th century, it finally makes its way to the British Isles, where Rome was struggling to maintain its hold on the southern regions against the constant pressure of the Picts and Scots in the north. As explained by the Farmerville Gazette, when the plague began decimating Roman forces, they enlisted the Saxons, a Germanic tribe with a long history of alternating between being an enemy and a client kingdom of Rome. The Saxons were brought in to fight the northern tribes, and promptly set down roots, forming the nucleus of what would become Anglo-Saxon Britain after the Romans were forced to abandon the area. They would rule England until 1066, when the Normans invaded and conquered.

Aztec Smallpox: destroying a civilization

As History points out, while many European countries thought they were bringing civilization to the New World, most of the Americas were already quite civilized and weren't exactly waiting with bated breath for a new religion. Instead, what the Europeans mainly brought were devastating diseases like smallpox, measles, and the bubonic plague. Since people in the Americas had never encountered these diseases before, they had no immunity, and so died by the tens of millions in various pandemics.

In the 16th century, the Spanish encountered the thriving Aztec empire and brought smallpox with them. The infectious disease so completely devastated the Aztecs that they were unable to resist the Spanish, despite the fact that the Spanish had only about 1,000 men. As explained by Past Medical History, relations between the two empires were friendly when first contact was established in 1517, but two years later the Spanish began their conquest, and by August 1521, the Aztec capital was gone. A few decades later, smallpox had killed about 90% of the Aztec population. There is no doubt that the disease was one of the main reasons the Aztecs succumbed so completely to the Spanish.

HIV/AIDS: The modern pandemic

It might seem like HIV and AIDS have gone away, but this modern pandemic still goes on. Although very effective treatments have made the virus survivable, this is still a disease that has claimed more than 34 million lives over the last few decades. Today, more than 37 million people are living with HIV, and it remains without a cure.

As reported by the Globe and Mail, the AIDS pandemic initially disproportionately affected gay men, and as a result was often ignored or deprioritized by healthcare institutions. Although the gay rights movement had begun years before, the AIDS crisis galvanized the LGBTQ+ community. CNN explains that the lack of response to the AIDS pandemic and the ongoing persecution of the LGBTQ+ community translated into a lot of anger, which inspired many to become activists. Prior to the AIDS pandemic, for example, there weren't many national organizations for LGBTQ+ people, but many sprang up in the wake of the disease.

Whereas prior gay rights efforts had focused on freedom of expression rather than legal and political rights, being demonized and left to die by society changed the thinking of many activists. In many ways, the current state of LGBTQ+ rights is in large part due to HIV.

The third cholera pandemic: the breakthrough

When you read about the third cholera pandemic, you might wonder how many there have been, and the answer may surprise you. The World Health Organization reports that we're still in the midst of the seventh, which officially began in the 1960s.

According to History, cholera has been around for a very long time, but first rose to global prominence in the early 19th century in India, the site of the first pandemic. The disease came and went in waves over the years, with a third pandemic hitting in 1851. Up until then, the disease had remained mysterious — no one knew exactly how it was transmitted or what caused it, frustrating efforts to stop its spread.

But, as explained by History of Vaccines, the third cholera pandemic provided some key insights. In 1854, while people were again dying all over the world from cholera, Italian doctor Filippo Pacini examined the intestines of victims and noticed they were filled with odd, comma-shaped particles. He wondered if they were the cause of the disease. Pacini made several correct deductions based on his research, including the way cholera draws fluid and electrolyte loss at a massive scale. He suggested treating the disease with infusions of water and salt. At almost the same time, a London doctor named John Snow figured out the source of a cholera outbreak: a public water pump. These breakthroughs changed how we approach pandemics and contributed to our modern understanding of cholera and disease transmission.

The rinderpest: the cow disease

Rinderpest is a disease that affects cattle and other animals including buffalo, pigs, and giraffes. It doesn't affect human directly, but an epidemic of the disease definitely affected humans indirectly.

As explained by the New York Times, certain strains of rinderpest (which literally means "cattle plague" in German) are so bad they can kill as much as 95% of a herd in a very short period of time. New Frame reports that in the late 19th century, rinderpest tore through Africa, starting in the north of the continent and making it all the way to South Africa in just 10 years. Many countries in Africa at the time relied on their livestock for their food and economy, so watching up to 90% of their herds die off was a cataclysmic event. As a result, the African economy almost collapsed, and the epidemic is considered one factor that pushed the desperate Boers to go to war with England.

The devastation made Africa too weak to resist the colonial ambitions of Europe. EuropeNow explains that the two are inextricably linked, as European ambitions in Africa undoubtedly introduced the disease in the first place, and the societal collapse that resulted made many African nations easy pickings for European powers. The history of Africa might have been very different if rinderpest had not arrived there.

Yellow Fever in Haiti: a successful slave rebellion

The slave rebellion and subsequent war that led to Haiti becoming the first independent country in Latin America was due to the courage and intelligence of the Haitians themselves, especially leaders like Toussaint Louverture, but they had a powerful ally in a yellow fever epidemic.

Napoleonic France had gained control of the island from the British in the late 1790s. According to Montana State University, when Louverture led the largest slave rebellion in history and became the true authority on the island, Napoleon sent 20,000 troops from an army widely considered the best in the world at the time. The French quickly defeated the rebels, and were confident they would pacify the island permanently. Then they started to die.

As ABC News explains, the native Haitians were acclimated to yellow fever, while the French were not. About 80% of the French forces died of the disease, forcing Napoleon to abandon the island. This in turn convinced him to give up his ambitions in the Americas altogether, leading to the eventual sale of Louisiana to the United States, a significant step towards the U.S. becoming a global power. All because of a yellow fever epidemic.

The 1901 bubonic plague breakout in Cape Town

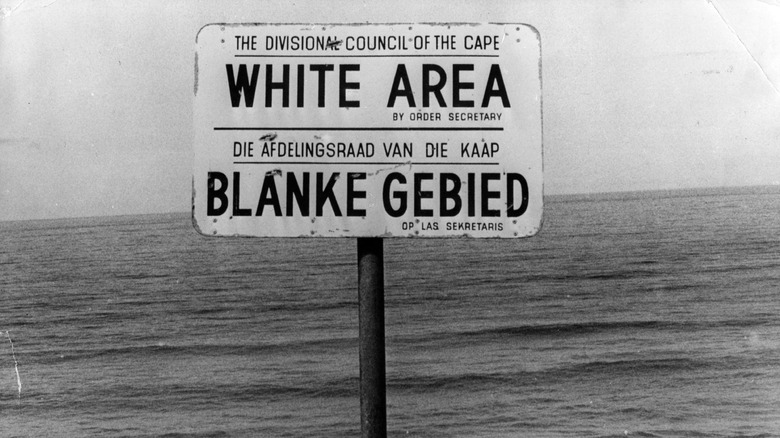

The South African system of apartheid — legal and institutionalized racial segregation — only became official policy after the National Party gained power in 1948, as reported by History. Prior to that there was plenty of racism and brutal oppression of Black people in the country, but it was all unofficial. But the legislation that created the apartheid system had its roots in a devastating pandemic.

As Johns Hopkins Medicine explains, in 1901, our old friend bubonic plague hit South Africa hard. In their efforts to deal with the disease, many officials in Cape Town saw an opportunity to act on their racist ideas, and they used the plague as an excuse to remove the city's Black population by force, transferring them to quarantine stations. Journalist Mark Gevisser explains that while white South Africans were also moved to quarantine stations as needed, they were largely allowed to return to their homes when the crisis had passed. Most of the Black population would never return to their homes, and the success of the program carried out under the banner of a health emergency became the foundation for apartheid a few decades later. The quarantine basically became permanent, and over time it was codified into law.