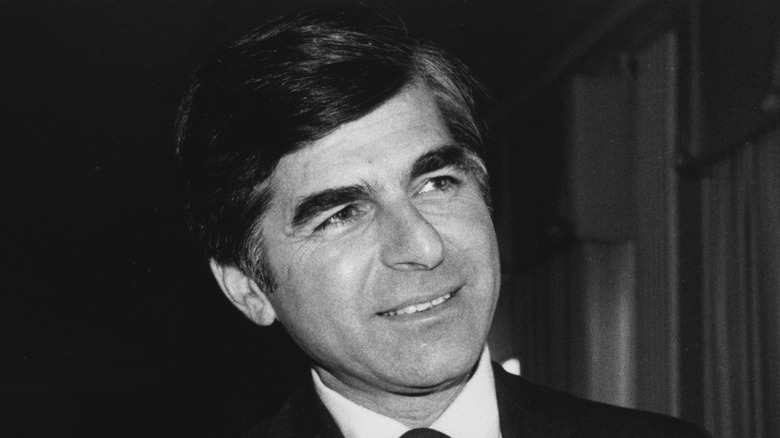

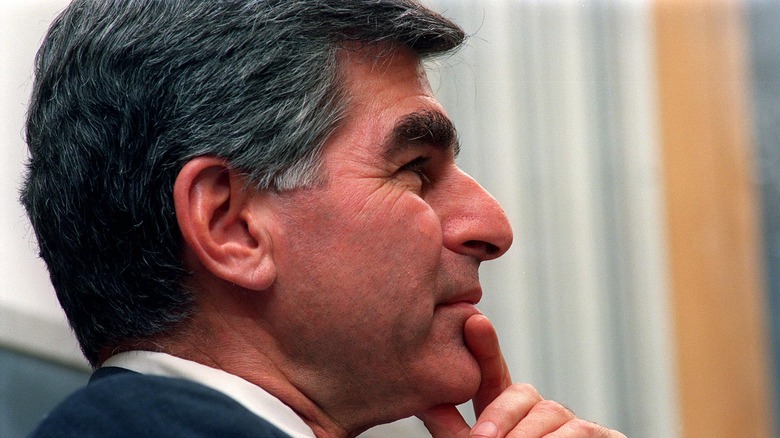

What Happened To Michael Dukakis?

Michael Dukakis is remembered for a variety of reasons. Some never forgot the infamous tank photo. Others may remember him being mentioned in the film "Donnie Darko." But for many, Dukakis is the man who lost to George H.W. Bush Sr. in the 1988 presidential election and put the country on the path of the Bush dynasty. Dukakis himself has claimed responsibility for putting the Bush family in the White House.

Although Dukakis was governor of Massachusetts for 12 years in total, for the nation, Dukakis disappeared as quickly as he appeared. After losing the race, Dukakis never made another bid for the presidency ever again. And almost immediately, he stated his intention to retreat from government service.

The United States will never know what a country under President Dukakis might have looked like and in many ways, he's often reduced to his failed presidential campaign. But his life is so much more than a year spent campaigning to be president. This is the story of what happened to Michael Dukakis.

Michael Dukakis' early life

Michael Stanley Dukakis was born in Brookline, Massachusetts on November 3rd, 1933. His father, Panos, was a Greek immigrant from Lesbos who came to the United States at 15, and his mother, Euterpe Boukis, was Aromanian-Greek arrived when she was nine years old. According to The Washington Post, Dukakis showed an early interest in politics. At the age of seven, he would sit with his 10-year-old brother, "listening to the Republican convention, and taking down the delegate votes, state by state."

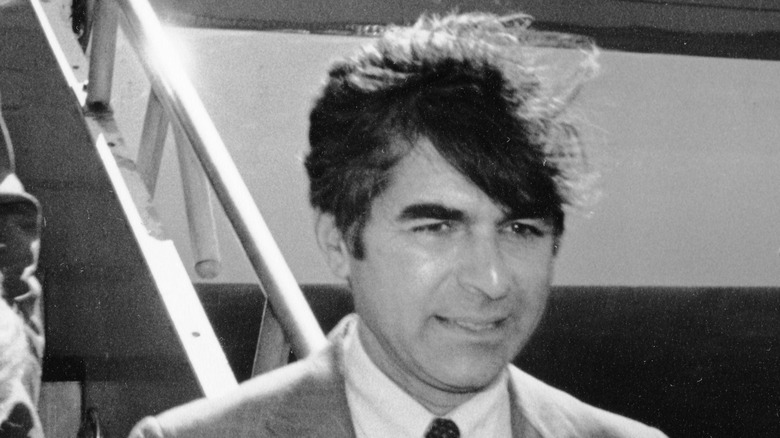

Attending Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, Dukakis was already talking about "becoming governor of Massachusetts." After graduating from Swarthmore in 1955 with a degree in political science, Dukakis was accepted into Harvard Law School, but he decided to defer his acceptance and enlist in the United States Army instead. While in the army, Dukakis was stationed in South Korea, where he served for 16 months, "providing support to the U.N. commission which oversaw the ceasefire" of the Korean War, reports Associated Press.

In 1957, Dukakis returned to his home state to attend Harvard Law School. And even before becoming a practicing lawyer in 1960, Dukakis took his first step into local government by winning a seat as a town meeting member in Brookline in 1959, a seat he would hold until 1970. According to the Massachusetts Municipal Association, the experience "shaped his life in politics and his strong belief that local politics is where real change can be made."

Joining the Massachusetts House of Representatives

In 1962, Michael Dukakis was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, where he served for eight years. According to CNN, during this time, Dukakis also ran for Massachusetts attorney general in 1966, although he was unsuccessful.

While Dukakis was part of the state legislature, according to Hobart and William Smith Colleges, "he sponsored the nation's first no-fault auto insurance bill." WGBH writes that Dukakis and his Democratic colleagues also sought to kill the sales tax that Republican Governor John Volpe wanted to pass, but the sales tax was eventually approved by votes "by an overwhelming 3 to 1 margin."

After losing another race for lieutenant governor in 1970, Dukakis decided to step out of the public sector for a time and focused on becoming a partner at the Hill & Barlow law firm, which he'd joined as an associate in 1960. In 1963, Dukakis also married Katherine "Kitty" Dickson. Dukakis would work for Hill & Barlow for three years, until on October 1, 1973, Dukakis announced that he was running for governor of Massachusetts.

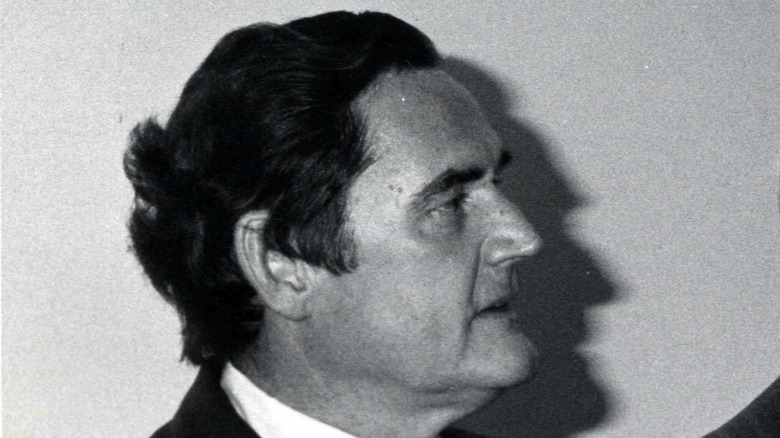

Michael Dukakis' first term as governor

In 1974, Michael Dukakis ran for governor of Massachusetts and beat the incumbent, Francis Sargent. Hellenic Resources Network writes that as Dukakis entered office, "he inherited a record deficit and record high unemployment." And Dukakis himself claims that at the time, Massachusetts was "one of the three or four most corrupt states in the country" and he set out to address the corruption. One of the biggest offenders was the Metropolitan District Commission, which was supposed to manage parks, waterways, and reservoirs as well as some highways. One of their divisions even included the Metropolitan Police.

According to "The Profession," at the time the Metropolitan Police were "badly organized, badly equipped, and unaccountable, they were lacking in procedures and discipline, with a growing high-level corruption scandal." And the Metropolitan Police weren't the only ones with scandals. The Metropolitan District Commission also controlled water and sewer treatment, which ultimately resulted in the pollution and subsequent court-ordered clean-up of Boston Harbor.

Dukakis pledged to dismantle the Metropolitan District Commission, but they had powerful supporters in the state legislature and the pledge was never carried out. And furious at being called out, the Metropolitan District Commission withheld their support from Dukakis during the 1978 gubernatorial primary.

Rejected by his own party

The Metropolitan District Commission wasn't the only enemy Michael Dukakis made during his first term as governor. By the time the gubernatorial elections rolled around again, even his own Democratic Party was rejecting him. Despite being the incumbent, the Democratic Party of Massachusetts decided to instead support Edward J. King, the former Director of the Massachusetts Port Authority, for governor instead. As a result, Dukakis lost the nomination to King by roughly 70,000 votes.

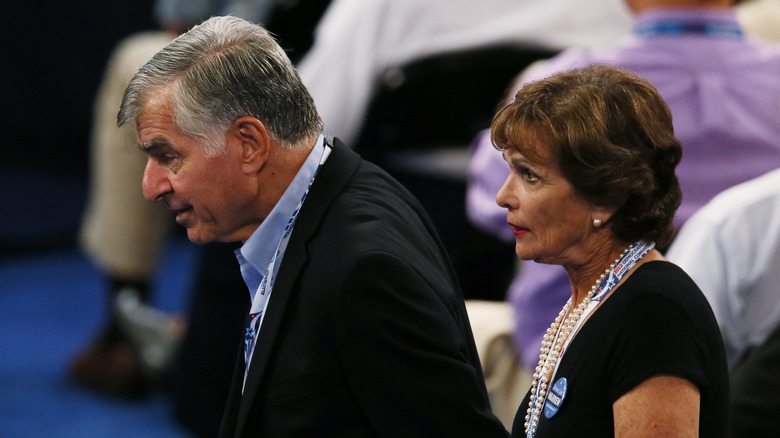

In 1978, The Washington Post wrote that Dukakis' "fiscal conservatism and spartan managerial style caused liberals to become disaffected early in his term." According to the Los Angeles Times, "Dukakis was abandoned by liberals, hated by businessmen, and ridiculed for his regulatory appointments." After experiencing what his wife Kitty called "a public death," Dukakis finished out his governorship and then took what he called "an involuntary sabbatical from public office."

For the following four years, Dukakis taught at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government as he figured out his next moves. Luckily, King was such a disaster that the Democrats couldn't wait to have Dukakis back.

Michael Dukakis' second governorship

In 1982, after reconciling with both the Metropolitan District Commission and the state Democratic Party, Michael Dukakis ran for governor of Massachusetts once more, this time defeating the incumbent King in the primary. The Washington Post reports that this time around, Dukakis showed off "a supple new political negotiating style" that allowed him to make more allies than enemies this time around. This allowed him to win re-election in 1986.

He also focused on expanding state programs when it came to housing and public transportation, "as the federal government [had] cut back." And Associated Press reports that at the time, Governor Dukakis was the "biggest tax raiser and tax cutter in Massachusetts history." While governor of Massachusetts, Dukakis' tax cuts totaled over $700 million, while he raised taxes "to the tune of $500 million." As governor, Dukakis stood on the progressive side on some social issues, such as opposing the death penalty and supporting public financing of abortions. Dukakis also "pumped lots of money into public education at all levels." However, he simultaneously opposed allowing gay couples to foster children.

In 1986, Dukakis was named by the National Governors Association as "the most effective governor." During this time, Dukakis also wrote three books: "State and Cities: The Massachusetts Experience" (1980), "Revenue Enforcement, Tax Amnesty and the Federal Deficit" (1986), and "Creating the Future: the Massachusetts Comeback and Its Promise for America" (1980), which was co-authored with his economic advisor Rosabeth Moss Kanter.

The 'Massachusetts Miracle'

In the 1980s, Massachusetts experienced a period of economic growth that was known as the "Massachusetts Miracle." Compared to the unemployment that the state had been experiencing previously, the 1980s saw an explosion in the tech industry and in financial services.

According to Maclean's, in the 1970s, industrial towns saw their factories close and unemployment skyrocketed up to 14%. But during the "Miracle," unemployment fell to around 4%. This was partly due to the "build-up of a high-tech industry — monumentally dependent on defense spending," writes Deseret News. Route 128 was especially known as "the home of computer companies," which for a brief moment was the Silicon Valley of the east coast, focusing on microcomputers rather than PCs.

Although many credited Michael Dukakis for the economic turn, and Dukakis himself happily tried to take credit for the "Massachusetts Miracle," some studies suggested that few of the initiatives by the Dukakis administration were a direct catalyst in the economic turnaround. And the growth didn't last: in the 1990s, Massachusetts faced another economic depression along with the rest of the northeast.

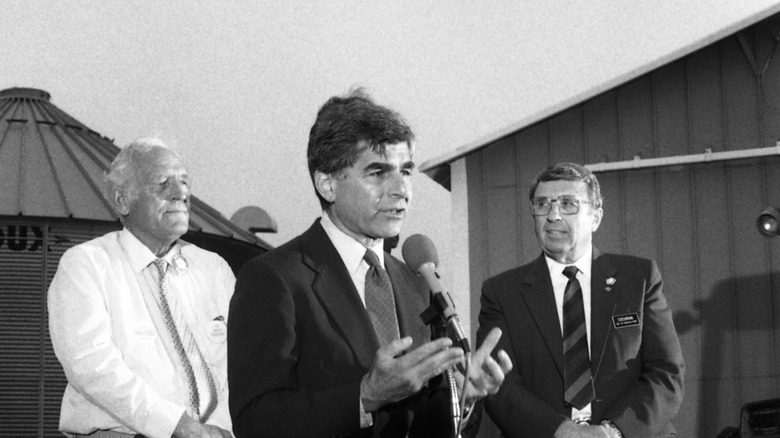

Running for president

In 1987, Michael Dukakis announced that he was planning on running for president, later choosing Lloyd Bentsen to be his running mate. But although Dukakis became the Democratic nominee with "highly favorable polls and party regulars rushing to his side," according to the Los Angeles Times, he soon came under attack. The Washington Post reports that although Dukakis claimed that the "election was not about ideology but competence," it was soon clear that he'd made a big misjudgment. His serious demeanor made him, the first Greek-American nominated to be president of the United States, the subject of snide descriptions such as "the one bland Greek in America" and "Zorba the Clerk."

The World also writes how Dukakis' support of furlough for prisoners was weaponized in an attack ad run by George H. W. Bush Sr. campaign that "wildly distorted the reality surrounding prison release programs." This attack ad not only had a huge impact on Dukakis' presidential campaign, but "it ultimately pushed a button of fear that marked the beginning of a 'tough on crime' era." Meanwhile, Dukakis made "a deliberate decision not to respond" until it was too late.

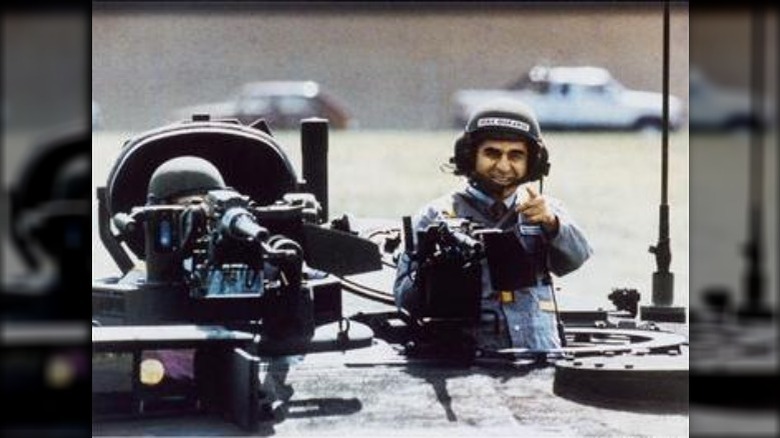

Another infamous part of Dukakis' campaign was the tank photo, which featured the candidate riding in a 68-ton M1A1 Abrams Main Battle Tank at a General Dynamics facility in Sterling Heights, Michigan. According to Politico, "The visit, meant to bolster the candidate's credibility as a future commander-in-chief, would go down as one of the worst campaign backfires in history."

Ableist attacks against Michael Dukakis

While running for president, newspapers began circulating a rumor claiming that Michael Dukakis sought treatment for depression in 1973, and potentially also in 1978. Several newspapers printed the rumors, including the Boston Globe and the Wall Street Journal. And when President Reagan was asked whether or not Dukakis should release his medical history, Reagan responded, "Look, I'm not going to pick on an invalid."

The Chicago Tribune reports that the ableist rumors and attacks led Dukakis to issue "a blanket denial," saying that he has never "suffered mental depression or had any other serious health problems." And according to PBS, journalist Robert Novak later claimed that Lee Atwater, the strategist for Bush Sr.'s campaign, tried to get him to slander Dukakis and claim that he was "having psychiatric problems." According to Psychology Today, not only was Dukakis forced to publicly state that he'd never sought mental health treatment, but "the candidate's personal physician had to refute the claim and to document that Dukakis was healthy."

The incident also underlined the idea that mental health was a shameful concept. This was clear from the fact that even though he was "leading in the polls before the comment [from President Reagan], Dukakis lost ground afterward."

Losing to Bush Sr.

Many considered the 1988 campaign to have been "one of the nastiest of the century." False personal attacks were levied from both sides, ranging from George H.W. Bush having an extramarital affair to Kitty Dukakis burning the American flag.

During one of the presidential debates, Michael Dukakis was asked if he would favor the death penalty if his wife was raped and murdered. And although Dukakis refused to dignify the loaded question with an emotionally charged response, saying instead, "No I don't, and I think you know Bernard, I've opposed the death penalty during all of my life and I don't see any evidence that it is a deterrent," according to NBC News, his answer "ruined" him.

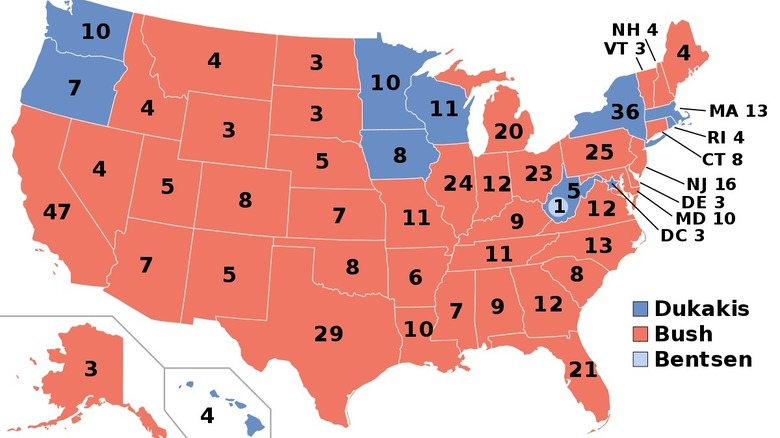

On November 9, 1988, George Bush Sr. defeated Dukakis to become the 41st president of the United States. And UPI writes that Bush Sr.'s victory was the first time in 152 years that a sitting vice president was elected to the presidency. According to Statista, Bush Sr. won 53% of the popular vote and almost 80% of the electoral votes. Comparatively, Dukakis only won Washington, D.C. and 10 states. In 2008, Dukakis said to U.S. News, "If I had beaten the old man [Bush Sr.], we'd never heard of the kid [Bush Jr.], and we'd be in a lot better shape these days. So it's all my fault ... We'd never be in this mess if I had done a better job. This has been the worst national administration I've ever lived under."

Finishing his term as governor

After losing his bid for the presidency, Michael Dukakis went back to being governor of Massachusetts for two more years. However, according to the Associated Press, the last two years of his governorship were "two years of political hell." When Dukakis returned to Massachusetts, the "Miracle" business boom had already petered out and "his popularity went with it."

The Washington Post writes that when Dukakis announced that he wasn't planning on running for reelection as governor, he "needlessly [made] himself a lame duck for two full years." At the same time, Dukakis was blamed for the state's "steep economic decline that made a mockery of his administration's revenue projections and precipitated the fiscal crisis that shredded Dukakis' reputation." Despite the fact that all of the states in the Northeast followed the same path as Massachusetts, Dukakis became "the emotional catch basin, the totem for everything bad that happened," according to "The Nowhere Man." At one point, Dukakis' approval ratings sank below 20%.

Teaching as a visiting professor

After retiring from government life, Michael Dukakis started teaching classes in health policy and political leadership. Sustainable Health Empowerment writes that after leaving office, Dukakis was a visiting professor at the University of Hawaii. There, he also "led a series of public forums" about reforming the country's health care system, according to UCLA. From June 1991, Dukakis also became a visiting professor at UCLA and a Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Northeastern University. The National Governors Association writes that Dukakis has been a visiting professor at several universities, including Harvard University.

Dukakis himself has said that "In many ways, working with students is the best thing I do. I feel strongly about this country and the world, and the importance of getting young people deeply and actively involved [in public service]."

Some of his students even go to work in public service, such as Rusty Bailey, Dukakis' former teaching assistant, who went on to become mayor of Riverside, California.

The North South Rail Link

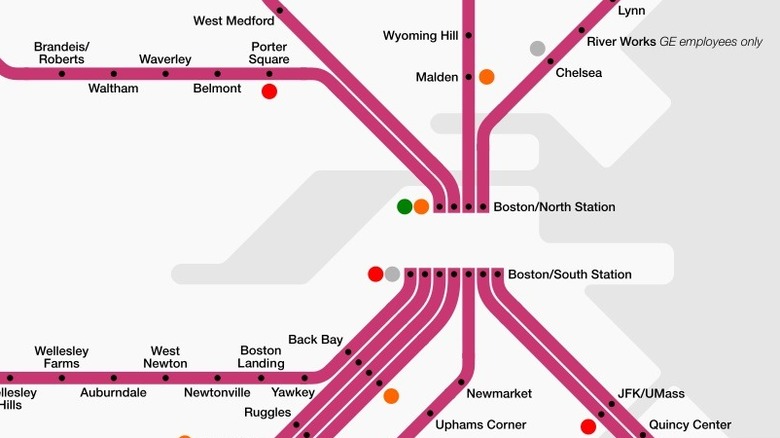

When Michael Dukakis was governor of Massachusetts, he not only rode the T, Boston's metro service, to work every day, but he invested heavily in the city's public transportation system. According to Boston Magazine, "Dukakis used $3 billion in federal money that had been allotted for highways to fix the T instead" and even worked to kill a highway plan in the 60s when he was in the Massachusetts House of Representatives.

According to WBUR, in 2014, South Station was renamed the Governor Michael S. Dukakis Transportation Center at South Station in honor of the former governor, who "oversaw a complete overhaul" of the station. During the ceremony, Dukakis stated that he was grateful for the honor, but he didn't see much point, since South Station will always simply be South Station.

Although Dukakis was able to see out much of his revitalization plan for the T, when the idea for the Big Dig came along, Dukakis had to give up one part of the project: the North South Rail Link. The North South Rail Link is a proposed pair of tunnels to connect North Station and South Station and although Dukakis had to give up his dream while he was governor, he never forgot about the possible connection. As of 2019, Michael Dukakis continues to advocate for the North South Rail Link and favors it over the proposed expansion of South Station, writes Universal Hub.