Can Your Personal DNA Code Be Sold To The Highest Bidder?

To many, personal genomics testing companies like 23andMe or Ancestry might seem like small miracles: an affordable, easy way to learn more about your heritage, discover family secrets, and annoy white supremacists (per PBS). When you dig a little deeper, though, there are at least a few complications. On the one hand, the results you'll get back are little more than educated statistical guesses (at least, according to Scientific American); but even assuming most of the testing is reliable and most of the results are accurate, there are profound ethical questions inherent in the technology that society have yet to really grapple with.

In a sense we've been down this road before: Remember when social media and other internet services were new and we all signed up, cheerfully agreeing to the terms of service we didn't read, only to discover a decade later that they had been mining far more of our data and selling it to far more entities than we ever could have imagined? In a sense, personal genomics is that all over again — except this time around, the data being collected, and potentially sold, is far more personal than your political views and where you eat for lunch. This is data literally coded into your body — and once you mail it in, it's entirely out of your control.

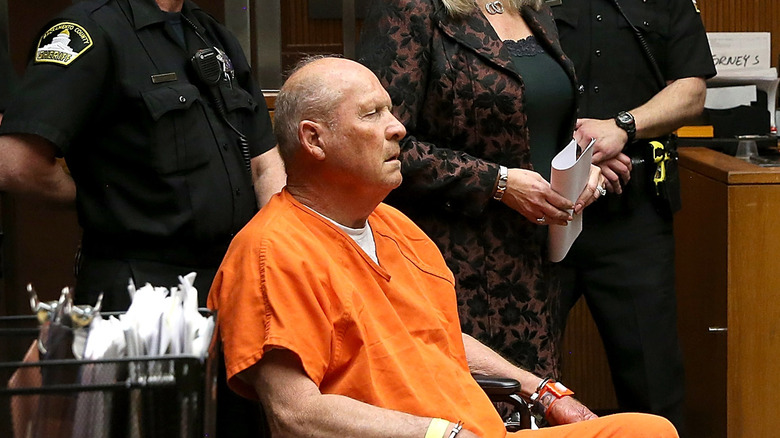

We've already seen personal genomics data used in law enforcement

There has already been at least one high-profile case where personal genomics data was used to put someone behind bars. The Golden State Killer — whom we now know was one-time police officer Joseph James DeAngelo — spent much of the late 1970s and early 1980s committing as many as 50 rapes, 13 murders, and dozens of burglaries around California, but the case on him went cold in the early 2000s (per The Los Angeles Times). In 2018, however, the authorities managed to track DeAngelo down via evidence collected from personal genomics website GEDmatch. The data wasn't even from DeAngelo himself; it was from a distant relative (via The Washington Post).

While it's almost certain that no one regrets DeAngelo being caught and sentenced to life for his crimes, the case does illustrate just how much can be done with DNA data, and how, when you give yours away, you're also giving away data on everyone related to you. And while all that info can be used for good — to catch criminals or develop miracle drugs, for instance — it's not hard to imagine it being used for less-pure intentions as well.

How safe is your genomic data?

The safety of your genetic data often comes down to how carefully you read the fine print and check the boxes. While the major genomics testing companies — 23andMe, Ancestry, and MyHeritage — all boast that they don't share data without the customer's permission (which seems like the bare minimum, but we guess no one asked us), the word "permission" is doing an awful lot of work here, as the different companies may offer "opt-in" — meaning you have to check a box to give them permission to share your data — or "opt-out" options that require deliberately unchecking a box.

According to The New York Times, some 40% of personal genomics companies on the market have no written policy at all regarding what they will and will not do with genetic data — and the industry is very much still in its "Wild West" phase, with very little regulation or transparency, leading Senator Chuck Schumer to call for a full investigation by the Federal Trade Commission.

If you've already used one of these services and are concerned about your data, know that the "big three" do allow you to retroactively revoke your permission (full instructions for each here). As CNBC points out, though, even once you've revoked permission, it's nearly impossible to verify your data has been deleted — or, for that matter, that your physical samples have been destroyed.