The Truth About Vladimir Putin's KGB Career

When Vladimir Putin was studying German at Saint Petersburg High School, it's likely that he already had his sights set on becoming a KGB agent. Whether or not he was already planning a presidential career is impossible to say, but if there's anything Putin demonstrated throughout his life, it's that his determination can take him anywhere he wants to go. It was this determination that led him to the local KGB branch to inquire about a career when he was a young adult.

Eventually, Putin went from being a KGB agent to deputy mayor to prime minister to president. And in April 2021, Putin signed legislation that would make it legal for him to run for two more presidential terms, meaning that theoretically, he could remain in power until 2036.

As a young KGB agent, near the tail end of the Cold War, Putin ended up assigned to a post in Dresden, Germany. Unfortunately, much of the information about his work as a KGB agent was destroyed, so it's difficult to discern which stories are legitimate, and some claim that Putin was simply a "low-level cog." But even if he didn't wield the greatest amount of influence, Putin's time as a KGB agent was likely to have been incredibly educational and influential. The fact that he's recreated Russia's FSB in the KGB's image speaks to how instrumental the agency is in his mind. This is the truth about Vladimir Putin's KGB career.

Putin's early life

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, then Leningrad, on October 7, 1952. Although his parents Maria Shelomova and Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin had two other sons, they both died as young children. As a result, according to Childhood Biography, they became "protective parents who did the best they could to keep [Putin] alive and well." Both of Putin's parents worked in factories after the Second World War, and Putin himself claimed in his official state biography, "I come from an ordinary family, and this is how I lived for a long time, nearly my whole life. I lived as an average, normal person and I have always maintained that connection."

Putin's childhood involved practicing judo and reading spy novels. And although he didn't do well in school at first, by the age of 14, he began to excel in school and was admitted to School No. 281 for high school, "which only accepted students with near-perfect grades."

Intellectual Takeout writes that around the same time, Putin decided to try his luck at becoming a spy and went to a local KGB branch. After asking for an appointment to discuss his future career, "the receptionist put him in touch with a dutiful senior agent, who advised him to join the military or study law but in any event not to contact the agency again." Five years later, Putin followed the senior agent's advice and went to study law at Leningrad State University.

Putin joins the KGB

While in university, Vladimir Putin made the acquaintance of Anatoly Sobchak, who was one of Putin's law professors and a man who would be important in his future political career. During his final year at Leningrad State University, Putin got his wish and was finally contacted by the KGB. After being put on a probationary track, Putin officially joined the KGB after graduating in 1975.

"The Two Worlds of Vladimir Putin" explains that initially, Putin was relegated to a local Leningrad branch rather than being given "a more desirable foreign post." And at the time, the local office was known by its agents to be a hopeless and ineffectual place. Former KGB agent Oleg Kalugin claimed that all they did was "harass dissidents and ordinary citizens, as well as [hunt] futilely for spies." And despite the millions of rubles and thousands of man-hours spent, between 1960 and 1980, not a single spy was caught by the local Leningrad KGB. In this office, Putin was a "low-level cog" and, according to Kalugin, a "nobody." Radio Free Europe reports that Putin's work in the Leningrad branch mainly consisted of "recruiting foreigners who came to the Soviet Union and Soviet citizens who communicated with foreigners or were going abroad."

In 1983, Putin also married Lyudmila Aleksandrovna Shkrebneva, who worked as a flight attendant for Aeroflot at the time.

What was the KGB?

The KGB, which stands for Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti, was the Soviet Union's intelligence agency, security agency, and secret police. Although the modern KGB was established in 1954, it had its roots in the Cheka, established by Vladimir Lenin in 1917, which in turn was transformed from "the remnants of the Okhrana," the imperial secret police.

According to PBS, the KGB had their hands in everything from running the Gulag labor camps to engaging in espionage: "There was a KGB officer assigned to every large enterprise or institution." And like most other intelligence agencies, the KGB conducted assassinations as well. Big Think writes that "in many cases, hard-to-detect poison was the weapon of choice."

The Atlantic reports that Vladimir Putin was recruited to the KGB by Yuri Andropov, chairman of the KGB, as part of the KGB's attempt to bring in people from different societal groups. During the 1970s, Andropov developed a recruitment scheme "to bring some new perspectives into the KGB and create an atmosphere for finding new ideas and dealing with the state's myriad problems."

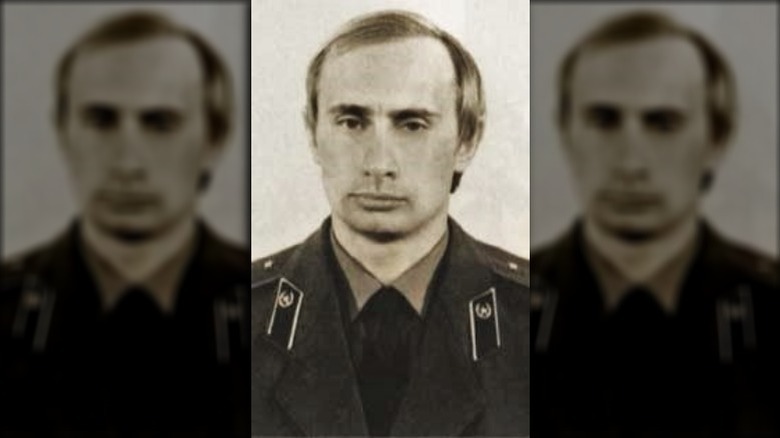

Putin in Dresden

In 1985, Vladimir Putin was assigned by the KGB to work in Dresden, East Germany while posing as a translator. Although not much reliable information is known about Putin's work in Dresden, his duties were similar to those in Leningrad. The Washington Post reports that Putin likely sought out "East Germans who had a plausible reason to travel abroad, such as professors, journalists, scientists, and technicians," who had acceptable cover stories that would allow them to "covertly link up with other agents permanently stationed in the West."

But according to Politico, it's possible that Putin had a far more significant role. A former member of the Red Army Faction, a far-left terrorist group that was active in West Germany and Germany from 1970 to 1998, claimed that Putin "worked in support of members of the group." Since the Red Army Faction had difficulties buying weapons in West Germany, they'd reportedly pass a list of weapons off to Putin and his colleagues, who would make sure that an agent in the West would set up a drop-off in a secret location. However, since most of the Red Army Faction members "are either in prison or dead," this claim is difficult to verify.

In 2015, an investigation by CORRECTIV revealed the likelihood that during his time in Dresden, Putin had more authority than initially suggested and was possibly responsible for a plan that involved blackmailing a "professor with pornographic material."

What did the KGB want with Germany?

The KGB was closely entwined with the State Security Service, or Stasi, in the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany. The Stasi participated in their own intelligence and secret police activities, but the tie between the KGB and the Stasi was underlined to the point that Stasi officers were considered "Chekists of the Soviet Union," according to "Stasi" by John O. Koehler. East Germany was also significant to the KGB because it lay on the frontlines of the Cold War. It was a place where agents could cross from one side to the other, and roughly "380,000 Soviet troops and Soviet intermediate-range missiles" were located in East Germany. According to a Stasi defector, "The GDR could do nothing without coordination with the Soviets."

The Stasi were also instrumental to the KGB with their surveillance operations. Monitoring hundreds of thousands of German citizens, the Stasi amassed millions of documents and the KGB kept tabs on those who could take justifiable trips abroad. In the secret Stasi files, over 10,000 people were marked as being "of interest" to the KGB.

According to The New York Times, in 2018, Putin's Stasi photo ID card was even discovered in the German archives. And although this doesn't imply that Putin worked directly for the Stasi, it proves that Putin "had access to the Stasi's headquarters in Dresden, most likely for recruiting locals for his intelligence work."

Putin's rise to lieutenant-colonel

Although Vladimir Putin may have initially been just another low-level employee who, according to Masha Gessen, "was reduced mainly to collecting press clippings," he was able to rise up the ranks. The Moscow Times writes that by 1990, Putin had risen to the rank of lieutenant-colonel, and the year before had been given a bronze medal "for outstanding service to the East German National People's Army."

However, the Times also notes that Putin was actually a major upon leaving, since one was usually given a "one-rank career bump on leaving, to help round out one's pension." With this in mind, it's unclear whether or not Putin ever had any sort of managerial power.

Little is known about Putin's Dresden years. There's even suggestions that he was there "to steal technological secrets" as part of Operation Luch. In the end, this is because both he and the KGB were "so effective at destroying and transferring documents before the collapse of East Germany," according to Politico.

The Berlin Wall falls

As the Berlin Wall came crumbling down, the tide started to turn. It took a month, but eventually the protests reached Dresden as well. Time Magazine writes that in 1989, German protestors gathered outside Vladimir Putin's office and threatened to storm the building, "demand[ing] the ouster of the Soviet-backed regime." In his official biography, Putin claimed that he frantically requested instructions from the Soviet Union, but "Moscow [was] silent." The BBC reports that Putin and his KGB colleagues decided in lieu of official instructions, they would simply burn all of the evidence of their work. Putin himself recalls, "I personally burned a huge amount of material. We burned so much that the furnace burst." According to Russia Beyond, it was arranged so "the most valuable documents were transferred to Moscow," but everything else went up in flames.

Although Putin realized that the GDR's collapse was "inevitable," according to The Atlantic, what he regretted was the fact that "the Soviet Union had lost its position in Europe, although intellectually I understood that a position based on walls and water barriers cannot exist forever. But I wanted something different to rise in its place. And nothing different was proposed. That's what hurt."

With the collapse of communism and German reunification around the corner, Putin and his family returned to St. Petersburg. In 1991, he "formally retired from the KGB," but in 2004, Putin himself claimed that "there is no such thing as a former KGB man."

Advising Anatoly Sobchak

Upon returning to the Soviet Union in early 1990, Vladimir Putin initially planned on doing a doctoral dissertation and working at Leningrad State University. But after his former professor Anatoly Sobchak was elected mayor of St. Petersburg in 1991, Putin joined his team as an advisor and "head of external relations." But according to "The Two Worlds of Vladimir Putin," "some say that he continued spying for the security services."

DW reports that Putin started working for the St. Petersburg city hall one year before Sobchak's election. And from his earliest days there, his work came under scrutiny when it was discovered that Putin "had permitted the sale of highly undervalued steel in exchange for foreign food aid that never arrived." An investigation recommended for Putin to be fired, but his termination never came.

From March 1994 to 1996, Putin served as Sobchak's deputy mayor. Putin was incredibly loyal to Sobchak, and when Sobchak narrowly lost the election in 1996, Putin left St. Petersburg. ABC writes that Sobchak continued to be Putin's mentor, "setting the ex-KGB agent on his path to the Kremlin." Leaving St. Petersburg and setting his sights higher, Putin set off for Moscow and the presidential administration.

Putin goes from deputy mayor to prime minister

Making his way up the political ladder, in Moscow in 1997, Vladimir Putin was named deputy chief of staff for Boris Yeltsin, President of Russia. The following year, Putin was promoted to being chief of the FSB, which was the latest iteration of the KGB. According to Radio Free Europe, in 1993, Yeltsin tried to "weaken the former KGB" and had taken the Vympel special-forces unit out of the FSB, but after Putin became the new director, he brought the Vympel unit back under the FSB in just two months.

Before long, Yeltsin promoted Putin once more, this time to the position of prime minister. Reuters reports that Putin was appointed acting prime minister by Boris Yeltsin on August 9, 1999. At the time, Putin was Yeltsin's fifth prime minister in under two years and CNN writes that Yeltsin claimed that Putin was "the ideal choice to handle the Caucasus crisis." But ultimately, many ended up criticizing Putin's brutal response to Dagestan and Chechnya.

But it was clear from the beginning that Yeltsin wanted Putin as his successor and on December 31, 1999, as Yeltsin resigned, he named Putin acting president.

Putin the president

As acting president, one of the first things that Vladimir Putin did was "pardon Yeltsin of corruption," which he'd been suspected of when he resigned. ThoughtCo writes that as a result of Yeltsin's resignation, elections were triggered for March 26th, 2000. Although Putin had arrived as a relatively unknown face, his "law-and-order platform and decisive handling of the Second Chechen War as acting president soon pushed his popularity beyond that of his rivals." And on March 26th, Putin was elected to the presidency with 53% of the vote. This would become the first of his four terms as president.

According to Der Spiegel, after being elected in 2000, Putin went to the old KGB headquarters in Moscow and joked to 300 former colleagues, "Instruction number one of the attaining of full power has been completed." After becoming president, Putin didn't leave his KGB roots behind. According to The Atlantic, during a national-security council meeting in 2016, "all but two of the eight people there were veterans of the KGB." Time Magazine reported in 2015 that the group of generals and KGB veterans in Putin's inner circle had started "to fully dominate political life in Russia."

Putin wasn't the only ex-KGB agent to become the head of an ex-Soviet republic. Heydar Aliyev, the third president of Azerbaijan, was the head of the KGB's Azerbaijani branch before becoming president.

'Former' KGB

As Vladimir Putin himself has said, "there is no such thing as a former KGB man," and many wonder how much his career in the KGB plays an influence today. Many of Putin's outspoken critics have ended up poisoned or murdered, a tactic often utilized by the KGB, writes NPR: "Proven or not, the radioactive death of [Alexander] Litvinenko hangs like a cloud over Putin's head." Meanwhile, the murder of Anna Politkovskaya is thought by some to have been a way to silence her reporting, which "exposed the Russian president as a power hungry product of his own (KGB-) history," according to RFI.

Some, like Foreign Policy, claim that with the FSB, Putin has essentially "reincarnated the KGB." Even its name, the Ministry of State Security, was the same name given to Stalin's secret service, which operated from 1943 to 1953. And by combining domestic surveillance with foreign espionage, under Putin the FSB has operationally returned to its KGB roots. In the end, even though the Soviet Union fell, "the institutions the security men worked in did not break down...the personal networks did not disappear," writes Catherine Belton.

And having seen what the sentiment of the masses can accomplish in Germany, in his time as president Putin has been quick to repeatedly suppress dissent, such as in 2012 when Putin's "security forces crushed a wave of anti-government demonstrations," writes First Post. Putin has also repeatedly jailed opposition leaders and activists.