Great Successes That Were Originally Done On A Dare

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Whenever stories about things done on a dare hit the news, they usually involve doing something profoundly foolish, and often have unpleasant outcomes: a visit to the police station for punching a camel, a two-hour surgical procedure after swallowing a steel spoon, or a brain infection, a 14-month coma, and death after swallowing a slug. After all, it's hard to resist the urge to prove oneself after hearing the words "I bet you can't..." or "I dare you to..." — and in such instances, ego and confidence work together to beat up common sense and stuff it in a box, consequences be damned.

Every once in a while, though, somebody decides to take on a challenge from a friend or a foe — and it ends up paying off in big and even bizarre ways. Here are a few examples of benefits that came from bet-prompted bravado (and exactly zero of these involve eating live animals on a dare).

Dr. Seuss wrote a children's book with only 50 unique words

It's tempting to think that writing a children's book is a piece of cake. Not really, though: Aside from telling a story with an interesting beginning, a satisfying finish, and a lesson or two somewhere in between, you'd also have to do it using words that your target audience could easily understand. Does that sound challenging enough? Well, imagine if you could only use 50 unique words throughout the book.

Those were the same parameters that Theodor Seuss Geisel aka Dr. Seuss had to work with when he wrote "Green Eggs and Ham," one of the most well-known children's books of all time (via the South Florida Reporter). Oh, and the dare that made this book possible? It happened because of an earlier book that was also born out of a friendly challenge. According to Learning First Alliance, Dr. Seuss wrote his book "The Cat in the Hat" when his friend, Houghton Mifflin education director William Ellsworth Spaulding, dared him to write a book that would be irresistible (and easy enough to understand) for first-grade readers.

Dr. Seuss would go on to write more books for early readers, each embracing limited vocabularies. Eventually, his publisher issued Dr. Seuss a seemingly impossible challenge: Write a book for children using only 50 different words. A short time later, Dr. Seuss served up "Green Eggs and Ham," a story about a fussy eater that employed 49 single-syllable words and one polysyllabic word ("anywhere").

An edgy animator created a mega-popular children's cartoon

If you grew up watching Cartoon Network in the early 2000s, you're probably familiar with the ridiculous schemes and quirky misadventures of the Eds. With six seasons of television episodes, console games, and even a movie (via ScreenRant), "Ed, Edd n Eddy" was easily one of the most successful and memorable cartoons of that era. It was notably darker than other animated shows made for its target demographic, but that's no accident.

The show's creator, Danny Antonucci, cut his teeth on cartoons for a more mature audience — and the main reason why "Ed, Edd n Eddy" exists is because a friend dared him to make a children's show (via Comic Book Resources). Fun fact: Antonucci's show almost ended up on a different network. When Nickelodeon wanted a bigger say in the creative direction of the yet-to-be-aired series, the adult animator took his proposal to Cartoon Network. "Ed, Edd n Eddy" hit the airwaves in 1999, almost instantly becoming a success with the channel's viewers.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Antonucci is reportedly quite protective of the integrity of his work. Back in 2017, one of the show's voice actresses, Erin Fitzgerald, shot down calls for the show's revival nearly two decades after it ended. According to her responses on social media, Antonucci intended the final movie to be the series' true swan song.

Agatha Christie wrote her first novel (and got rejected a lot)

Fans all over the world know the exploits of Hercule Poirot, the balding Belgian private eye who stars in many of detective fictionist Agatha Christie's written works. However, had it not been for Agatha's elder sister Madge, the legendary mustachioed sleuth — and quite possibly, the writer's robust literary career — wouldn't have existed in the first place.

CrimeReads recounts how a young Agatha, still wet behind the ears, wrote her first novel "The Mysterious Affair at Styles" as a response to her ever-competitive sibling's challenge. (Apparently, Madge was sure that her sister would botch the attempt.) And so, right in the middle of the First World War, Agatha began working on her debut detective novel while serving as a nurse in England. Things didn't really start out easy for her, though, as she had to deal with six publishers giving "Styles" the thumbs down before it found a home under The Bodley Head (via AgathaChristie.com).

Christie's vast knowledge and interest in assorted poisons, developed during this crucial time in her life, would later turn out to be a huge advantage in her 57-year career. Additionally, the Belgian refugees she met as a nurse served as the basis for much of Poirot's personality and characteristics. Perhaps most notably, "Styles" (and the other Poirot novels that followed it) helped form the backbone of the detective genre's so-called "Golden Age."

A disgusting drinking dare turned into a celebrated tradition

On paper, "finish off a shot of alcohol with an old, severed toe in it" might sound exactly like the kind of ridiculous drinking dare that only inebriated college students would find entertaining. It might surprise you to hear, then, that this exact drinking challenge is a time-honored tradition in Dawson City, Yukon, where the bartenders at the Sourdough Saloon dare newcomers to literally "dip a toe" (just not their own) in a whiskey shot: the rather unappetizingly named "Sourtoe Cocktail."

As per CBC News, this toe-tally unique tradition traces its roots to Capt. Dick Stevenson, who purchased a cabin in a remote location and found a mummified toe floating in a pickle jar. Legend has it that the original digit-turned-drink-garnish belonged to Louie Linken, an alcohol smuggler. His brother Otto allegedly had to chop it off his frozen foot to save his life, but opted to preserve the toe as a, well, memen-toe. When Capt. Stevenson discovered the toe many years later, inspiration struck. He formed the Sourtoe Cocktail Club, a group you could only join by finishing off a shot of whiskey with the object swimming inside it — and making sure that the mummified toe actually touches your lips.

Surprisingly, this disgusting dare not only caught on, but even persisted throughout the decades. In fact, according to Atlas Obscura, there have been at least seven replacement toes, because some patrons ended up swallowing them.

A teenager wrote a novel (that kicked off an entire literary genre)

Most teenagers spend the last of their pre-adulthood years living it up or stressing over their future. Not Mary Shelley, though. This literary prodigy ended up finishing an all-original novel that became a classic: "Frankenstein," the book that paved the way for every single science fiction horror story published within the last two centuries.

Shelley and her eventual husband Percy Bysshe Shelley spent the summer of 1816 in Switzerland, hanging out with their intellectually inclined friends. This circle included the famous English poet, Lord Byron (via the U.S. National Library of Medicine). While killing time in his villa, Lord Byron proposed a simple, straightforward challenge to his fellow literary enthusiasts: Write a ghost story (via Project Gutenberg).

Mary Shelley shared some of the details of her ideation process, which kicked into overdrive after a disturbing nighttime vision: "The idea so possessed my mind, that a thrill of fear ran through me, and I wished to exchange the ghastly image of my fancy for the realities around ... if I could only contrive [a story] which would frighten my reader as I myself had been frightened that night!" She also mentioned how her husband encouraged her to develop her story into a full-length novel. It was published in January 1818, spawning countless reinterpretations, a whole new genre, and a generation of bookworms who love pointing out that Frankenstein was the scientist, not the creature.

John Nash nailed a math mega-stumper because someone mocked him

Workplace conflict isn't exactly a new concept, and having difficult co-workers certainly isn't unheard of. At work, most people tend to avoid office confrontations altogether, letting microaggressions and passive-aggressive jabs slide just to keep the peace. And then there's U.S. mathematician John Forbes Nash Jr., who chose to deal with his colleague's mockery with the theoretical equivalent of a slam dunk.

For most of his professional career, Nash had a reputation for two things: being smart enough to solve problems so complex they send other mathematicians running, and being rather difficult to deal with (via the New York Times). Most of his colleagues at MIT learned how to coexist and communicate with him. Unfortunately, fellow professor Warren Ambrose wasn't one of them. Nash and Ambrose frequently got on each other's nerves; at one point, Ambrose told Nash point blank to solve a particularly challenging math problem, the embedding theorem for manifolds, if he were really "so good."

Nash took the dare seriously — and nailed it. In his own words from his Nobel profile: "I managed to solve a classical unsolved problem relating to differential geometry which was also of some interest in relation to the geometric questions arising in general relativity." Nash continued to build upon this work in the mid-1950s, to the point where he became a contender for the Fields Medal (one of the top awards for a mathematician) not once, but twice.

C.S. Lewis finished his science fiction trilogy

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien are two of the most well-known names in fantasy fiction. They were also very good friends (via Literary Traveler) — "like two young bear cubs sometimes, just happily quipping with one another," as told by John Garth in The Sunday Telegraph — whose writing careers took a while to fully bloom. A friendly wager between them helped pave their way towards literary immortality, enabling Lewis to finish a trilogy of science fiction books while planting the seeds of Tolkien's most memorable work.

During the mid-1930s, the 38-year-old Lewis and the 45-year-old Tolkien challenged each other to write science fiction stories. Tolkien decided to write about time travel, while Lewis opted to tackle space travel. This dare resulted in Lewis finishing "Out of the Silent Planet," the first of his Space Trilogy. Over the course of seven years, he was able to complete his three-part epic with 1943's "Perelandra" and 1945's "That Hideous Strength."

Meanwhile, Tolkien never finished his story (titled "The Lost Road"). Interestingly enough, some of the bits and pieces from that unfinished tale factored into his Middle-Earth mythology, the backdrop for "The Lord of The Rings" and his other successful high-fantasy novels.

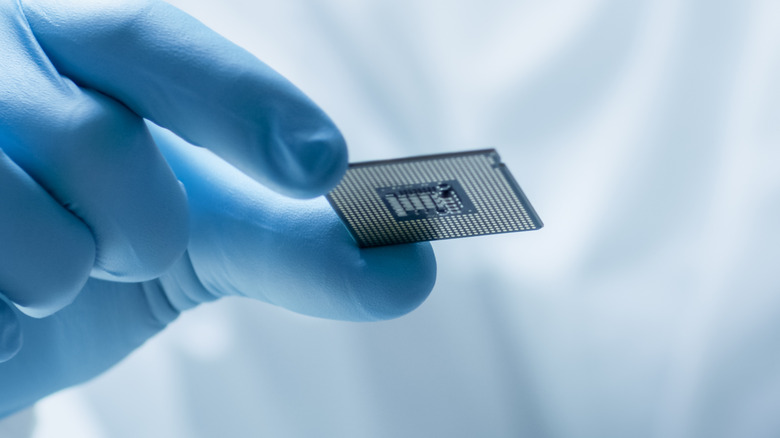

A micro-sized wager helped usher in a brand-new scientific field

When electrical engineer William McLellan first read physicist Richard P. Feynman's famous 1959 lecture "There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom" (via the Wall Street Journal) in a magazine, he noticed Feynman's odd but interesting wager: a challenge to create a working electric motor no bigger than 1/64 of an inch cubed. Initially writing it off as a task that required too much effort, McLellan told BBC News that he decided to work on it in June 1960.

Five months passed, and McLellan succeeded where many failed. He shared how Feynman almost dismissed him as one of the "cranks" that didn't quite get the point of his wager, until he showed the doctor his functional mini-motor through a microscope. Even more fascinating was how McLellan made the motor even smaller than Feynman specified, just "to be sure that there wasn't a wire hanging over it." Feynman acknowledged that it met his set parameters, likely making him one of the few people in history to be delighted to lose $1,000.

Over two decades later, another engineer, Eric Drexler, also found inspiration in Feynman's words. Partially sparked by the potential for rearranging and restructuring atoms that Feynman mentioned, Drexler wrote a 1981 paper that included the word "nanotechnology," a word that, unbeknownst to Drexler, was used seven years earlier by Japanese scientist Norio Taniguchi (via Nature). Nevertheless, many count Drexler's work (alongside Feynman's) among nanotechnology's major conceptual cornerstones.

The world was introduced to a pioneering aviator

Even without considering the dare she took on, Elinor Smith Sullivan led an incredible life as an aviation prodigy. As a pilot, Sullivan soared, literally and figuratively. According to Woman Pilot Magazine, obtaining her license at 16 made her the youngest pilot of her time. And a year later, in 1928, she set a death-defying world record on a dare: She flew under all four of the East River suspension bridges in New York.

Smithsonian Magazine revealed that the dare originated from some men who "doubted her expertise," which means it must have been quite a relief when ace aviator Charles Lindberg himself wished her good luck before her flight. To accomplish this feat, Sullivan took the time to study the environmental conditions, as well as the bridges themselves, before actually attempting to do the challenge in the middle of October.

The rest, as they say, is history — and by successfully pulling off what no other pilot had done before, Sullivan's fame skyrocketed. She flew for three more years before she willingly grounded herself because of marriage and four kids. However, after the 1956 death of her husband, Sullivan returned to flying. She only stopped when she turned 89 in 2001, long after she had cemented her place in aviation history.

A fertilizer salesman made the worst film ever (that gained a massive cult following)

Take a fairly generic horror plot (a family vacation gone terribly awry) that was literally written on napkins, add in some amateur photography, slipshod editing, and accidentally comical lines, and turn it into a movie on a measly budget of just $19,000 (about $158,000 in today's money). That's exactly how fertilizer salesman Harold P. Warren made "Manos: The Hands of Fate," a movie that Entertainment Weekly called "the worst movie ever made." It was so bad that when it debuted in 1966 at the Capri Theatre, it drove one of its lead actors to embarrassed tears (via El Paso Times).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, "Manos" came into existence purely because of a bet. Overestimating his own filmmaking capabilities, Warren boasted to a Hollywood screenwriter acquaintance that making a movie from scratch was easy as pie, and that he could do it himself. Predictably, the finished product was less than stellar, a box office bomb that nearly died in obscurity.

That is, until the writers of the TV comedy series "Mystery Science Theatre 3000" ended up with a copy almost three decades later. Deeming it lampoon-worthy, they dedicated a 1993 episode to mocking the so-bad-it's-good movie (via AV Club). Soon, the movie gained a massive cult following, spawning a prequel, a sequel, a video game, and even a Blu-ray restoration of the original film, made possible via a crowdfunding project that reached almost five times its target amount.

An American sergeant's celebrated flag-bearing marches

Picture this: The American Civil War had just ended, and tensions between the North and the South (and the British folks who sided with them) appeared to be at an all-time high. Things looked so bad that some believed the simple act of walking through unfriendly territories while bearing the Stars and Stripes was tantamount to suicide. Enter Sergeant Gilbert Bates, who successfully proved this notion wrong not once but twice — and in both instances, on a dare.

In November 1867, Bates and a friend struck a bet: If the sergeant could make it through the South's "rebel states" safely while carrying the American flag, he would receive a dollar per day of his absence (via American Heritage). And so, he traveled on foot for three months from Vicksburg, Mississippi to Washington, D.C. with the flag in tow, passing through the Confederate States along the way. Receiving hospitality and kindness throughout his journey, Bates emerged victorious, as reported in The Pantagraph.

Five years later, Bates entered another wager. This time, another friend bet him a thousand dollars that he couldn't repeat his flag-bearing march across England without being met with hostility. Ever the optimist, Bates took on the challenge, marching 640 kilometers from the border of Scotland to London. Again, he was warmly received by the British, showering him with gifts and hospitality wherever he went. Interestingly, Bates refused his winnings, saying that the impact of his mission already made the trip worth taking.

Isaac Newton's notes became one of science's most important books

Popular science communicator Neil deGrasse Tyson has repeatedly made the claim that Isaac Newton invented calculus "on a dare." While this apocryphal account is far from accurate, the renowned English thinker did finish one of his greatest contributions to science because of a bet.

According to an episode of BBC Story of Science, back in 1684, astronomer Edmond Halley participated in a bet with other men of science. It hinged on proving that the elliptical orbits of planets were bound by mathematics. Halley consulted Newton to help him figure this out; to his astonishment, Newton remembered solving that exact problem about two decades earlier, back when he had to stay at home during the Great Plague of London (via FlipScience). After some time, Newton found his notes and sent them to Halley. The latter convinced the former to continue developing — and eventually publish — his research (via Discover Magazine).

Thus, in 1687, Newton released one of the most significant books in science history: the "Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica," which contained his Three Laws of Motion, his Law of Universal Gravitation, and many other concepts that help form the foundation of modern physics. Not bad for a paper that spent two decades covered in mothballs, right?