The 18th Century Conspiracy To Make Kentucky Part Of Spain

Inarguably the most famous traitor in American history–in fact a name synonymous with treason in American minds–is Benedict Arnold, the American military officer who defected to the British side during the Revolutionary War. However, there is another general, a contemporary of Arnold's, whom biographer Andro Linklater, paraphrasing historian Fredrick Jackson Turner, calls "an artist in treason." President Theodore Roosevelt said of this man, "In all our history, there is no more despicable character," which, for America, is an incredibly high bar to clear.

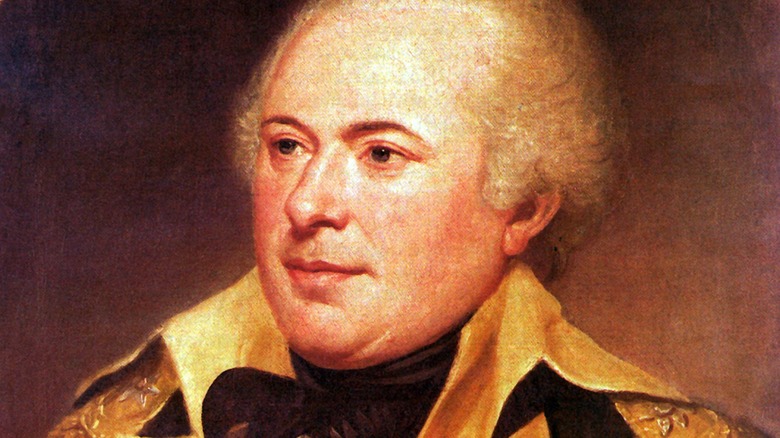

The man in question is James Wilkinson, a statesman and soldier who did his best to sell out America at every available opportunity. His most notable act of treason was the so-called "Spanish conspiracy," in which Wilkinson basically took it upon himself to sell Kentucky to the Spanish in exchange for barrels full of silver dollars. What follows is the bizarre story of how something like that happens.

The state of the States after the Revolution

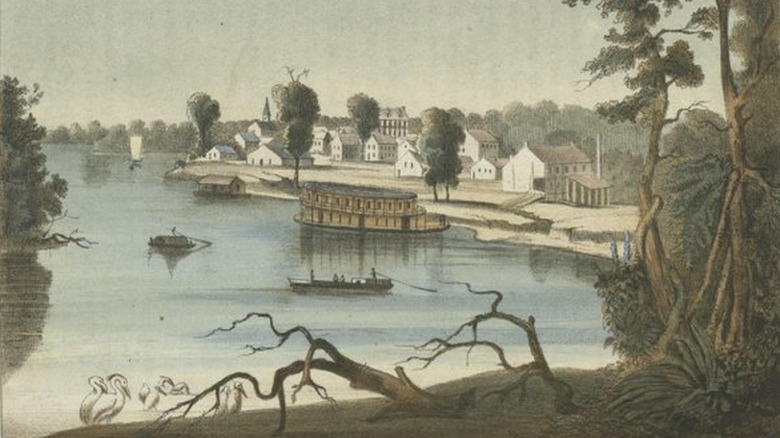

In the 1780s, following the American colonies' success in the War for Independence, the state of America was still evolving. While westward expansion was part of the former-colonies-now-nation's view for the future, the land mass we now think of as the United States of America was not yet solidly America from sea to shining sea. As History Naked explains, while Americans from the eastern states were pushing across the Appalachians into western territories such as Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee, one of the most important ports on the North American continent–New Orleans–and arguably its most important waterway–the Mississippi River–were under the control of the Spanish.

According to Encyclopedia.com, in 1784, the Spanish prohibited Americans from accessing the Mississippi River for commercial purposes. Additionally, the Spanish were at that time inciting raids by the Creek Indians against American settlers in the western territories, cutting off many trade routes. The United States, not wanting to start a war with Spain right after finishing one with Britain, didn't make any efforts toward regaining rights of navigation for its citizens, which was, to say the least, frustrating for American settlers in the Cumberland Territories of Kentucky and Tennessee. The use of waterways was essential for an early America that had not yet developed a reliable road system. Without access to the Mississippi, farmers in the Cumberland territories suffered enormous financial hardship.

The despicable James Wilkinson

One of the many Americans to head west following the Revolution in order to seek his fortune was one James Wilkinson, an average soldier who had basically charmed his way into the position of brigadier general during the Revolutionary War. As the Northern Kentucky Tribune explains, Wilkinson was born in 1757 in Maryland to a wealthy family and studied medicine at the University of Pennsylvania for about a year and a half before deciding, "Nah, I'm good." At about this point, the American Revolution was breaking out, so Wilkinson made his way to Boston to try his hand at being a soldier. When he got there, apparently three semesters of medical school was sufficient education for him to be commissioned as a captain. Soon, in a bit of foreshadowing, Wilkinson was working as an aide to Benedict Arnold.

When given the assignment of reporting the American victory at Saratoga to Congress, Wilkinson took his sweet time getting there and, once he did arrive, played up his own role in the victory so much that Congress promoted him to Brigadier General at the age of 20. In another example of Wilkinson failing up, he was a part of a conspiracy to replace George Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, but accidentally gave up the game with a bunch of drunken gossiping. He was subsequently appointed Clothier-General of the Army, but he resigned for "lack of aptitude."

Wilkinson comes to Kentucky

In the 1780s, pretty much any man who had attained the rank of general in the Continental Army would have been pretty firmly planted in the eastern states with property and decades of social connections. James Wilkinson, however, had seen his familial estate sold off in order to help cover his father's debts. As a result, as Hanover Historical Review explains, Wilkinson made his way along with a sizable wave of East Coast emigrants to Kentucky in the hopes of finding his fortune there. Wilkinson's history as a veteran and general was impressive to his Kentucky neighbors, and by 1785 Wilkinson was deeply entrenched in Kentucky politics, including the territory's movement toward separation from Virginia and statehood of its own.

According to the Northern Kentucky Tribune, Wilkinson, together with his wife Nancy and their infant son John, bought land near what is now Louisville, bought more land by the Licking River, and established a store in Lexington. Now having a vested interest in both the commerce and politics of Kentucky, Wilkinson found himself increasingly concerned with the crop surpluses caused by the closure of the Mississippi River. Kentucky was sparsely populated at the time, even by 18th century standards, and so shipping goods down the Mississippi to New Orleans and beyond was the only way Kentucky produce could reach the market. What was a con man like Wilkinson with more charm than loyalty to do?

The Spanish conspiracy begins

In 1787, James Wilkinson decided to take a load of tobacco and other Kentucky produce down the Mississippi River in defiance of Spanish law. As the Northern Kentucky Tribune explains, however, he also took with him all of his skills of charm, flattery, and ambition, because his goal wasn't to export one load of tobacco, it was to gain audience with Esteban Miro, the Governor General of Louisiana, a.k.a. the highest-ranking officer of the Spanish Empire in North America. Wilkinson had the goal in mind of establishing a Kentucky monopoly on trade along the Mississippi, and he had the most buckwild plan to reach that goal.

Wilkinson told Miro that he represented the interests of a number of "notable Kentuckians" who were pursuing seceding from the US in favor of becoming a vassal state of Spanish North America. What Wilkinson asked was for Spain to allow unfettered trade for Kentucky farmers along the Mississippi, and in exchange, Kentucky would become something of a "buffer state" between the United States and Spain, representing Spanish interests in the West and protecting them from the US taking the Mississippi River by force. If the Spanish refused, Wilkinson said, he would take this offer to the British. Miro was interested in Wilkinson's offer, and this was the beginning of both the so-called "Spanish conspiracy" and Wilkinson's long and storied career as a traitor against the US.

The unbreakable code of Agent 13

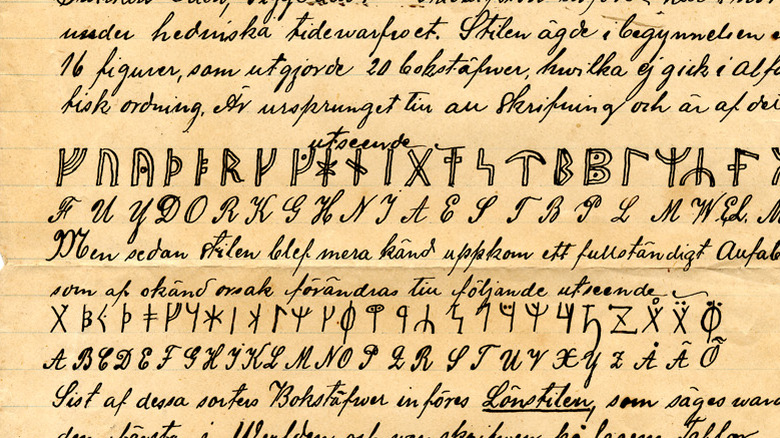

Wilkinson, because of his charm and status among Kentuckians, was able to make a good impression on Governor Miro, and he was able to spend the entire summer in Louisiana among the Spanish. As the Northern Kentucky Tribune explains, it was at this time that Wilkinson officially became an agent of the Spanish crown. The Hanover Historical Review says that Wilkinson went so far as to sign a declaration of expatriation from the United States and an oath of allegiance to the King of Spain. It was decided that Wilkinson would sell American state secrets to the Spanish Empire, which was done through coded messages. According to NPR, these messages were sent as rows of numbers in groups of four. While this code was never broken in his lifetime, it was based around a Spanish cypher called "number 13," for which reason Wilkinson was known among the Spanish as "Agent 13," and in fact, he refused to be referred to by the Spanish as anything else.

James Wilkinson's newfound allegiance to Spain had considerable effect on his position on Kentucky statehood. While at previous conventions Wilkinson had spoken in favor of Kentuckian independence from Virginia, he now opposed statehood and the newly drafted US Constitution, as his vision for Kentucky involved secession from America and a place in the Spanish Empire. Perhaps surprisingly, he had quite a bit of support in this idea among Kentucky landowners.

The many betrayals of James Wilkinson

As History Naked explains, James Wilkinson's main role as an agent of the Spanish crown was to pass along information to Manuel Gayoso, who was the governor of the Natchez District in what is now Mississippi. In this correspondence, which History Naked calls "breathtaking in its treasonous content," Wilkinson expressed to Gayoso his desire to become "the George Washington of the West," which seems a bit ironic in the light of Wilkinson's previous involvement in a conspiracy to overthrow George Washington, but okay. This planning largely seemed to involve passing on information to the Spanish about which other influential Kentuckians were, like Wilkinson, open to trading their allegiances for Spanish money.

He also used his position as spy to strike down any potential competitors. In 1789, another American general, George Morgan, also had the idea of establishing a Spanish colony in the western American territories. This colony was established on the western side of the Mississippi at the juncture with the Ohio River in what is now Missouri, where it is still called New Madrid. Wilkinson worried that Morgan's colony would cut into his planned Kentuckian monopoly on river traffic, and so he used his connections to the Spanish governors to sling mud at Morgan's name, calling him, with apparently no self-awareness, "ruled by motives of the vilest self-interest." These tactics actually worked, and New Madrid failed to receive the funding it needed from Spain.

The benefits of treason

While James Wilkinson provided information to the Spanish that they could use against American interests along the Mississippi River, he clearly wasn't doing it out of the goodness of his heart. As Encyclopedia.com explains, Wilkinson received for his efforts an exception to the Spanish policy of confiscation of commercial goods sent down the Mississippi, giving him a monopoly on American trade through New Orleans. While this alone would have been enough to make him rich, he also was paid handsomely for the information he passed along, as well as the promise of a royal pension and an appropriate appointment within the government when Kentucky became a vassal of Spain. In a rare moment of thinking about others, Wilkinson also secured the promise that when Kentucky became a Spanish colony the inhabitants would be allowed to continue to speak English and to enjoy religious freedom (that is, they wouldn't have to become–yuck–Catholics).

Through this arrangement, Wilkinson became extraordinarily wealthy. While his activities did, of course, raise some suspicions, in general he was hailed as a hero by Kentuckians for his efforts to open up trade routes. His popularity guaranteed his presence within Kentucky politics, where he argued against the US Constitution and in favor of Kentucky separation not only from Virginia, but from the United States as a whole. He maintained this position and lifestyle for a staggering 10 years without consequence.

A narrow escape

Although James Wilkinson was able to get away with his treason for years, that doesn't mean he never came close to getting caught in his traitorous actions. As NPR explains, Wilkinson often found himself on the brink of being revealed due in large part to the Spanish crown's preferred method of paying him: giant piles of silver dollars. Thousands of dollars in heavy coinage is not the easiest thing to hide or to transport, and Wilkinson often had trouble sneaking in piles of loud metal cash without suspicion. He usually hid the coins in barrels packed with coffee, sugar, or rum, but even this wasn't a surefire method. In one notable instance, one of Wilkinson's messengers was carrying $3,000 in coins back to him when the messenger was murdered by the five Spanish boatmen transporting him, who subsequently stole the money.

These murderers then went all around the Kentucky territory spending their stolen money. All five were eventually arrested and brought in front of a Kentucky magistrate who didn't speak any Spanish. As luck would have it, the Spanish murderers, who could have blown up Wilkinson's spot, didn't speak any English. It turns out that the only person who could act as a translator between the two parties was Thomas Power, who was also a Spanish spy. Power lied, saying the boatmen confessed to being motivated by greed, and Wilkinson lived to spy another day.

A traitor leads the US Army

As a double agent, James Wilkinson would never have been happy only playing one side of the field. As a result, while he was selling state secrets to the Spanish, he was still vying for power within the US military. As the Northern Kentucky Tribune explains, he managed this in large part by leading Kentucky volunteers on raids against Native American villages in what is now Indiana. Wilkinson's efforts in this area led to his reinstatement in the US Army as Lieutenant Colonel, and disastrous losses by another general along the Wabash River led to President George Washington looking for a new commanding general. The two main candidates for this position were Wilkinson and Anthony Wayne. Despite Wayne's reputation for rashness and susceptibility to flattery, rumors of Wilkinson's unsavory dealings led to Wayne's appointment as commander. To soothe Wilkinson's legendarily fragile ego, Congress promoted him to Brigadier General, second only to Wayne himself within the US Army.

Not satisfied with being number two, Wilkinson put all of his efforts toward undermining Wayne, a nice change from his typical practice of undermining the United States as a whole. Wilkinson would sell information he would learn from Wayne about military strategy and movements to the Spanish in New Orleans. Wayne learned of Wilkinson's treason, but died before he could report it. This left James Wilkinson, traitor and spy, as the Commander of the United States Army.

Wilkinson tries to kill Lewis and Clark

During James Wilkinson's tenure as Senior Officer of the Army, he continued to pass on US secrets to the Spanish for silver. According to NPR, one major piece of information that Wilkinson sold to the Spanish came in the wake of the Louisiana Purchase. Wilkinson explained to his Spanish masters the intention of the Lewis and Clark expedition to chart this new US territory and its ulterior motive of finding an overland route to the Pacific Ocean. Wilkinson told the Spanish that they should send armed troops to find and kill Lewis and Clark, and that they should build fortifications to block US westward expansion, advice which the Spanish took. As it happens, Lewis and Clark only narrowly avoided being captured by the Spanish at this time due to their taking a cautious route toward St. Louis.

Despite nearly ruining the US's development of the Louisiana Purchase, Wilkinson was nevertheless named Governor of the Louisiana Territory by President Jefferson in 1805. As the Northern Kentucky Tribune explains, this move permanently removed him from his long-held position in Northern Kentucky but did not stop him from passing on secrets to the Spanish and otherwise conspiring against the United States. Despite being suspected of sedition by every president from Washington to Madison, Wilkinson kept being assigned positions of power within the US government.

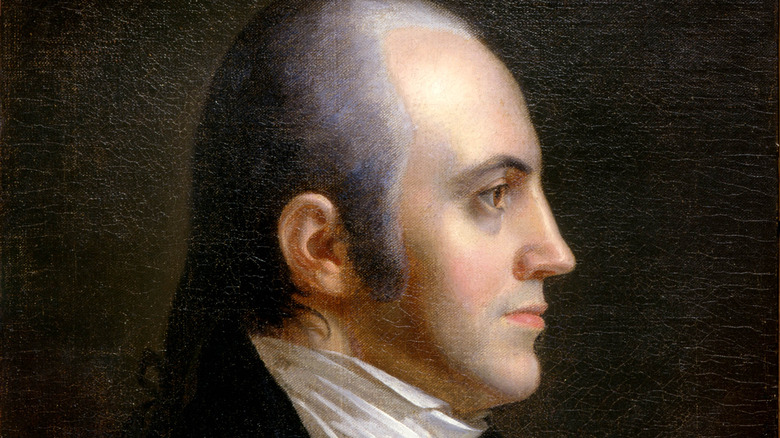

The other plot to betray America

No plot against America was too good for James Wilkinson, it seems. According to Encyclopedia.com, in 1804 Wilkinson began correspondence with Aaron Burr, whom you might recognize as the guy who shot the $10 bill man in the hip-hop show or milk commercial. What you may not know is that while serving as vice president under Thomas Jefferson, Aaron Burr plotted with a cabal of wealthy landowners to have the southwest territories of the United States secede and form their own independent nation. While Wilkinson's role in this conspiracy is not clear, it is well known that the two men corresponded frequently, and Wilkinson definitely knew what Burr was planning. It is also known that Wilkinson provided Burr with a boat and a letter of introduction to the Spanish governor in New Orleans, and Burr later visited him in St. Louis when Wilkinson was the Governor of the Louisiana Territory.

However, it wasn't long before people noticed the suspicious connection between Wilkinson and Burr, and Wilkinson realized that his name was being buzzed about in Washington in dangerous ways. In order to clear himself, Wilkinson wrote a desperate letter to Jefferson blowing the whistle on Burr's conspiracy and proclaiming his own loyalty to the US. Wilkinson himself was assigned to lead troops to New Orleans to arrest Burr's co-conspirators, and soon after Burr himself upriver in Natchez.

The end of Wilkinson's conspiracies

Following the end of Burr's conspiracy, James Wilkinson's shady dealings with both the Spanish and Burr started coming to the surface. Nevertheless, Wilkinson somehow managed to keep any kind of charge or punishment from sticking to him. As the Northern Kentucky Tribune says, Wilkinson escaped, over the terms of four different US presidents, three court-martials and four congressional investigations. Military historian Robert Leckie said of Wilkinson, "He never won a battle or lost a court-martial." NPR explains that the reason Wilkinson continually escaped capture, despite years of suspicion and numerous betrayals by co-conspirators, is that officials could never break his codes and unambiguously prove his connection to the Spanish empire. It wasn't until the 20th century that historians uncovered documentation proving his treason.

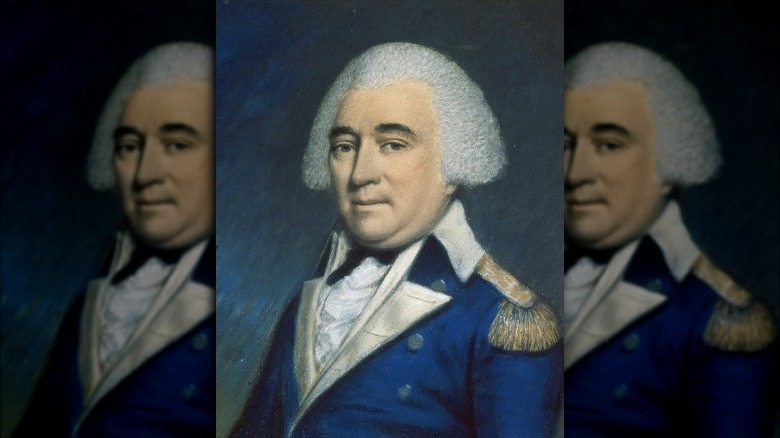

Despite getting away with his crimes, Wilkinson's Spanish conspiracy was, as History Naked explains, largely defanged in 1789 anyway by the opening of the Mississippi waterways to western commerce provided a duty was paid, and then fully killed in 1795 when Pinckney's Treaty (named for Thomas Pinckney, pictured) gave the US full access to the river and control of the Spanish fort in what is now Memphis. Wilkinson was retired from the military following the War of 1812 and ultimately moved to Mexico City, where he died an expatriate in 1825 at age 68 after composing what Encyclopedia.com calls "a turgid three-volume defense of his career."