Can Someone 3D Print Your Face Using Your DNA?

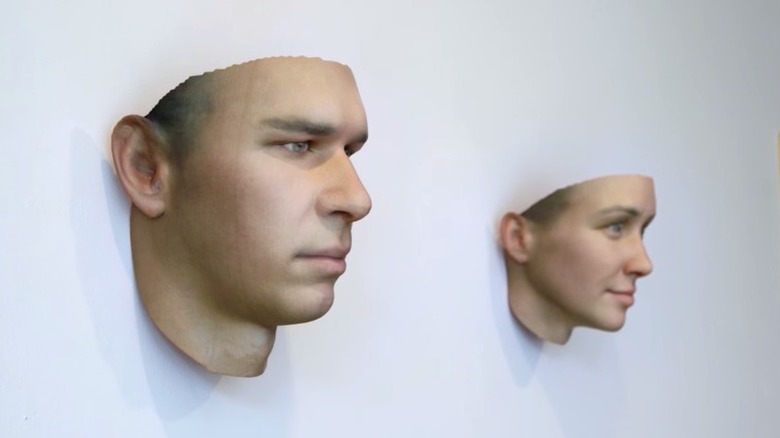

In the early 2010s, news outlets began to report on the movements of a woman from New York named Heather Dewey-Hagborg, whose image was shared widely alongside that of an array of 3D printed faces mounted on walls behind her. None is instantly recognizable, but each is familiar in that they could easily be a colleague, a friend of a friend, a person you glance at on a bus or train without giving it a second thought. One, in fact, resembles Dewey-Hagborg herself.

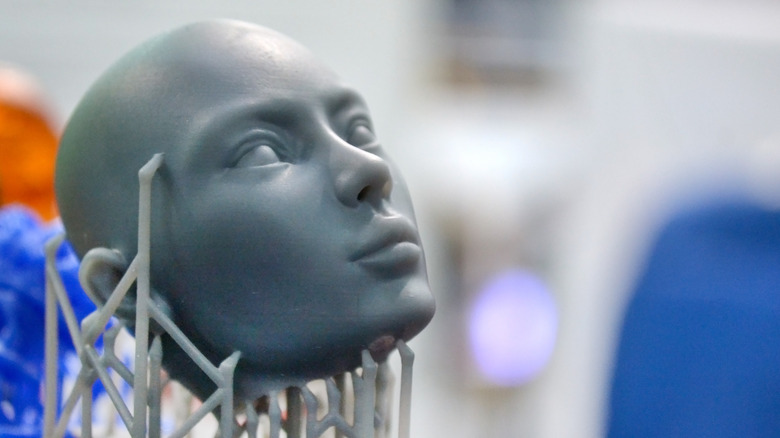

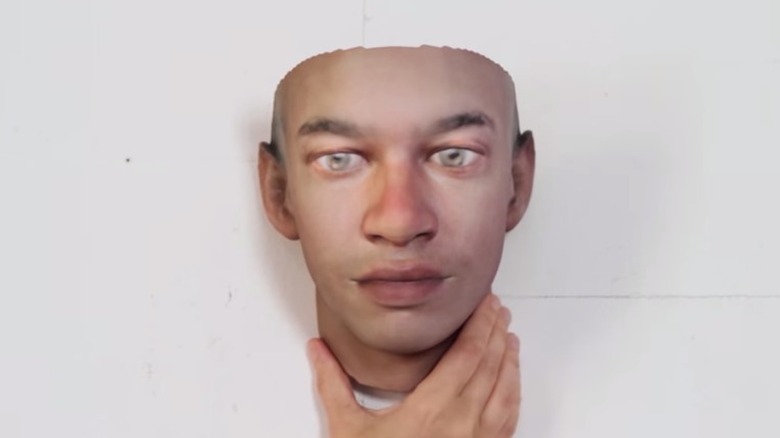

But this is no self-portrait, nor are any of the other disembodied faces those of people that Dewey-Hagborg has ever actually met. As reported by Live Science, these were supposedly the faces of random, anonymous New Yorkers, which Dewey-Hagborg had generated from samples of DNA she had gathered from discarded artifacts — cigarette butts, coffee cups, samples of hair — found in the streets of the city. The faces had then been 3D printed, giving each artifact a human origin for all the world to see.

Many internet users commented on how creepy Dewey-Hagborg's actions were. Had we really just stumbled into the brave new world that such images suggested? Who in the world would want a 3D printer to be able to reproduce their likeness using DNA from a trace of saliva, from a single human hair? And was Dewey-Hagborg really the genetic terrorist that she appeared to be? As always, the answers to these questions were slightly more nuanced than it first appeared.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg: bio-hacker?

"I began by actually collecting forensic samples in public spaces, monitoring the streets and bathrooms of New York," explained Heather Dewey-Hagborg (via Live Science), who then took the collected samples to be analyzed in a nearby lab. Using technology that Forbes describes as being similar to that which police investigators employ at crime scenes — a process called a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) — Dewey-Hagborg was then able to identify aspects of the DNA that would give her an insight into the physical characteristic of the unknowing person from whom the sample had been taken.

But Dewey-Hagborg's actions are not those of a privacy-invading rogue biologist, nor a vigilante using genetic data to catch track down litterbugs. Actually, she is an artist, and her project, titled "Stranger Visions," is intended to spark a debate about the need for privacy at the dawn of what she has called "genetic surveillance," according to Wired, which quotes her this way: "If I have your genome sequence, theoretically I can do more than just know very personal things about you. I can clone you. I can impersonate you. It's a sci-fi scenario but it is a reality now."

The danger of genetic surveillance

If you have been reading about the work of Heather Dewey-Hagborg in absolute horror for the last few paragraphs, you can breathe a sigh of relief: The faces that she has generated for "Stranger Visions" aren't in fact direct replicas of the people whose DNA she gathered on the streets of New York. According to Wired, the artist analyzed the samples for general indicators of how they looked, such as "gender, ancestry, eye color, hair colour, freckles, lighter or darker skin, and certain facial features like nose width and distance between eyes," Dewey-Hagborg explained. She added that the 3D printed faces "look more like a possible cousin than a spitting image of the person themselves. The reason for this is multifold, but the primary reason is the research on facial morphology, the way human faces differ, is still in very early stages ... you can't discount the role environment plays in expression of genes."

The message of Dewey-Hagborg's work is this: Whether we like it or not, the technology by which such facial cloning might be achieved on an individual level is well within the realm of possibility. We're not there just yet, but we should think long and hard about the ramifications of such technology before it arrives. "You wouldn't leave your medical records on a subway for just anyone to read," said Dewey-Hagborg, via Live Science. "It should be a choice."