How Building The Palace Of Versailles Helped Advance Science

Europe is full of palaces, though arguably none are as famous as the Palace of Versailles. Located just a few miles outside of Paris, the Palace of Versailles served as the principal residence of France's royal family from the late 1600s until the French revolution in 1789, per Encyclopedia Britannica. The palace is known worldwide for its extravagant design, from gilded columns and crystal chandeliers to ornate fountains and sprawling gardens. Today, the palace has 2,300 hundred rooms, per the Château de Versailles website, and the entire palace grounds takes up an area several square miles in size. The Palace of Versailles now serves primarily as a museum, but this month, the palace also opened up its first-ever hotel, according to Forbes. (For those curious, the price runs around $2,000 a night.)

While the Palace of Versailles has major architectural, cultural, and historic value, "science" is not a word that would often come to mind in relation to it. But the Palace of Versailles was actually quite central to the advancement of 18th-century French science. The Château de Versailles website states that the palace was home to a number of scientific demonstrations in electricity, manufacturing, and even balloon flight. Kings Louis XV and Louis XVI were also both interested in science, and collected many scientific instruments at the palace. Likewise, the palace was home to a large collection of exotic plants and animals; this "menagerie" helped advance zoology, botany, and even anatomy (through dissection).

Building the Palace of Versailles led to advancements in water transportation technology

But the Palace of Versailles didn't just contribute to science in these obvious, intentional ways. As it turns out, the very construction of the Palace led to a number of unintended advancements in science and technology.

These developments primarily centered around water transport. The Palace of Versailles wasn't in the best location to receive running water, as it sits on a plateau elevated several hundred feet above the nearest river, the Seine. To draw that water up and over to Versailles — especially in order to supply the garden's large fountains — King Louis XIV relied on some of the top scientists and engineers of France. Per the Château de Versailles, these thinkers designed and constructed "an elaborate system of pumps, aqueducts, and reservoirs," with many of these breakthroughs going on to revolutionize how water was transported.

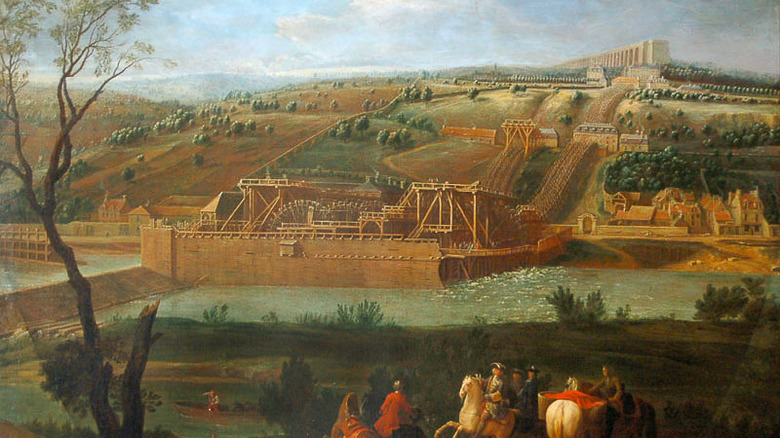

One particularly ingenious device was the "Marly machine." Per MarlyMachine.org, this large, wooden structure was built over the course of seven years, and was unveiled to Louis XIV in 1684. As The Guardian reports, the gigantic machine included 14 large paddle wheels, 259 pumps, and three sinks, all serving to elevate water from the Seine by roughly 500 feet. Once elevated, that water was fed into the Louveciennes aqueduct, where it then flowed directly to Versailles.

The original Marly machine remained in use until 1817, at which point it was updated and rebuilt. It was ultimately transformed into an electrical generator which was used until 1963.