The Messed Up History Of Australia's Emu War

In the spring of 1932, the Emu War was declared in Australia. By the start of summer, the emus had been declared the victors. But the story runs much deeper than just a handful of soldiers armed with machine guns facing 20,000 emus: The Emu War is a story of colonization, veterans, farmers, and a government that failed its people.

The Australian government also technically declared the Emu War without realizing, since their minister of defense sent soldiers to fight the emus without actually consulting the prime minister. But at the end of the day, soldiers and their machine guns were no match for flightless birds that cared little for organized formations.

Although the Emu War only lasted for a few months, emus and farmers continued fighting for decades. Eventually, some farmers decided to kill two birds with one stone, and memories of the emu war were supplemented by emu farming. Now, emus are a protected species in Australia, can only be killed with a license, and are believed to number greater than they did before European colonization. But the legacy of the Emu War lives on. This is the messed up history of Australia's Emu War.

Soldier settlements in Australia

During World War I, Australian state governments introduced soldier settlement schemes to provide returning veterans with a source of income. According to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, approximately 9 million hectares of land were given to returning veterans, creating around 23,000 farms across Australia.

The New South Wales State Library writes that the Returned Soldiers Settlement Act was introduced in New South Wales in 1916. This act allowed soldiers who had been honorably discharged to "apply for Crown Lands if they had served overseas." Various districts specialized in particular industries. In Tasmania, soldiers worked as dairy farmers, in Queensland, they farmed cane, and in South Australia and New South Wales, fruit industries were established.

By definition, "Crown Lands" are lands that were dispossessed from Aboriginal people during the colonization of Australia. And although many Aboriginal men served in the Australian Imperial Force, when they returned to Australia, many of their applications for soldier settlement allocations were denied for no apparent reason other than their Indigenous heritage. There were a handful of successful applications, but those who were successful were all "fair-skinned enough to be considered 'substantially European.'"

The land that the soldiers were given often wasn't suitable for farming, and while soldiers could get advances of money for equipment and seeds, "many men learned the hard way that they were not cut out to be farmers and the land they received would not sustain them and their families" (via ABC).

The Wheat Marketing Bill

The "Wheat Belt" was established in southwestern Australia. Roughly 5,000 soldiers settled in the area, but by the 1920s, almost one third had given up. Farmers were forced to diversify their crops in order to sustain themselves.

As the 1929 Great Depression led all commodity prices to drop worldwide, the newly elected Prime Minister James Scullin proposed a plan to help Australian farmers. History Nuggets writes that Prime Minister Scullin told Australian farmers that if they produced more wheat, he'd ensure the passage of the Wheat Marketing Bill "in order to guarantee the farmers a minimum price for their 1930 crop."

Unfortunately, according to "A New Idea Each Morning" by Wendy Way, "the proposed price guarantee evaporated in political wrangling." By September 1931, the government had abandoned their plan to compensate farmers for their losses, and as a result, farmers were only able to sell their wheat for less than half of what they'd been expecting. Many called it "one of the greatest disasters in Australian economic history."

It took four tries to pass a relief bill, but by the time it passed in 1931, the damage had already been done. Prime Minister Scullin's Labor Party lost the elections that year, and when Joseph Lyons became prime minister, he canceled the relief bill. After suffering two disastrous years in 1930 and 1931, wheat farmers decided to withhold their wheat until they were able to get a fair price for it.

Declaring emus a pest

Around the same time the Australian government started giving plots of land to veterans, Western Australia changed the status of emus from "endangered" to "vermin." This was largely due to the fact that the land given to farmers was being invaded by emus searching for water. Although emus typically migrate from the northeast to the southwest in the spring, History Nuggets writes that "they are notoriously unpredictable in the speed and distance they travel," as well as the number of birds that will be traveling in a group.

According to the Journal of the Department of Agriculture, the Australian government declared emus to be "vermin" in 1922 and instituted a bounty for them, paying for emu beaks. Not only were the emus themselves a problem for the farmers, since they ate the crops, but they also made large holes in the fences surrounding the farms. The fences were essential for protecting the farmers' crops from rabbits, an invasive species that had been brought by English settlers "to have familiar hunting targets."

Emus, meanwhile, are indigenous to Australia. A flightless bird that can stand over 6 feet tall, according to How Stuff Works, they're opportunistic grazers and will eat anything from grass to nuts. So when they passed the wheat fields on their migratory path, who could blame them for enjoying the buffet?

The migration of 1932

In 1932, when farmers were withholding their wheat, they were simultaneously forced to contend with a massive migratory group of emus. The emus came along their migratory path in the fall, and initially, as roughly 20,000 emus descended into the Campion District, farmers tried to fight against them themselves.

According to Scientific American, by late 1932, the 20,000 birds were "wreaking havoc on the marginal wheat farms of the beleaguered veterans, and even these men, trained riflemen, who felled thousands of the mighty birds, could not put a dent in their numbers." At one point, some boys reportedly killed as many as 27 emus in a single day by riding around on bicycles and "swatting the birds in the head with sticks as they sped by," writes History Nuggets. A similar endeavor was attempted with a truck, but the truck's engine was too loud and scared away the emus.

The farmers panicked because not only did they need the harvest to make money, but they also needed it as "leverage against the government." After a while, the emus had also started catching on to what was going on, so despite continuing to eat the farmers' crops, they also became wary of humans and wouldn't allow them to get close.

However, since the farmers didn't trust the Ministry of Agriculture, they instead turned to the minister of defense for help.

Requesting military aid

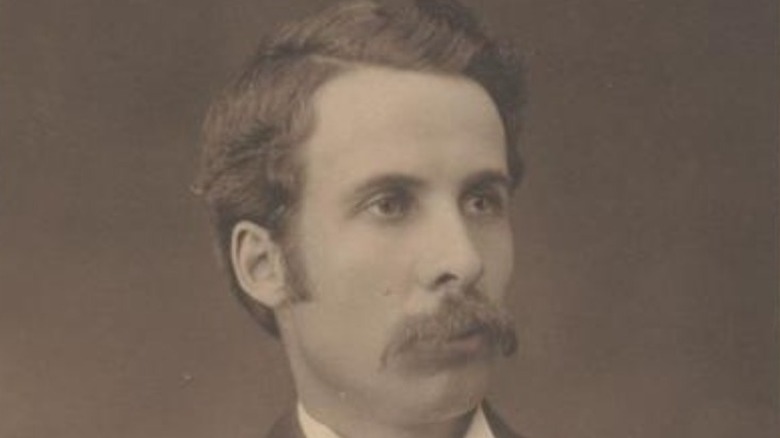

Representatives of the soldier-farmers reached out to Sir George Pearce, the minister of defense (pictured). One account states that a letter was written to Sir Pearce, while other accounts claim that the soldier-farmers sent a group to see Sir Pearce personally. Either way, they reached out to Sir Pearce specifically to request machine guns in order to combat the emus.

Sir Pearce was intrigued by the plan, and when he discussed it with the commandant of the Fifth Military District, Brig. A.M. Martyn, they decided that it could be a useful training exercise for their own soldiers. And according to Modern Farmer, Sir Pearce also decided to send "a Fox Movietone cinematographer along, recognizing an opportunity to show the rest of the country how hard the government was working to better the lives of all Australians during the Great Depression."

The local Society for the Prevention of Cruelty was reportedly consulted, and they approved the idea as long as their inspectors could verify "that the animals were treated humanely." And when Col. Hoad of the Australian Light Horse found out about the project, he insisted on making an order for 1,000 feathered emu skins in order to use their plumage for his horsemen's hats.

Sir Pearce decided that machine guns would be provided as long as they were operated by professional soldiers who know how to use them. Additionally, farmers would have to provide all of the ammunition, food, and lodging for the soldiers.

Waiting for a month

The operation was initially planned for early October 1932. Two machine gunners, Sergeant S. McMurray and Gunner J. O'Halloran, were assigned to the mission and given two Lewis light machine guns.

Along with Major G.P.W. Meredith and the Fox movietone cameraman, they headed to the Campion district. According to History Nuggets, "The Farmer's Agricultural Bank [had also] agreed to front the government for the ammunition, to be repaid out of the farmers' future profits," so the men brought 10,000 rounds of ammo with them.

Modern Farmer writes that the group arrived "ready to decimate the interloping emus," but the rain arrived just as they did. As a result, the emus scattered for a month. Per their agreement, the farmers housed the men over the course of the month in the town of Perth. When the rain finally ceased and the emus returned, the soldiers headed once again to the Campion district. On their way, they saw a group of 40 to 50 emus, and Major Meredith decided that it was time to start the culling.

First shots fired

The first shots were fired on November 2, 1932, as the soldiers sought to gun down the group of emus. The soldiers also rallied around 50 local farmers to help herd the birds with their trucks toward the machine gun. However, as History Nuggets notes, "emus do not stampede in a straight line as many other animals do, but scatter in all directions when startled, so when the cars roared toward their position, they split into small groups and bolted in all directions." Plus, emus can run up to 40 mph, which made it even more difficult to focus on a target. As Scientific American writes, "the birds answered their organised assault with inspired chaos."

The emus also stayed beyond the range of the machine guns, coming no closer than 1,000 yards. And although Sergeant McMurray fired at the emus, all of the shots missed. The soldiers asked the locals to try herding the birds once more, and although the birds remained out of range, this time Sergeant McMurray was able to gun down six of the emus. The first blood of the Emu War was shed.

Army vs. emu

The next day, the soldiers managed to kill nine emus, but not before the birds "devastated a local farm." Two days later, the soldiers ambushed a group of 1,000 emus. Since they had waited quietly for the emus to approach them, the birds were hit at point-blank range, and between 10 and 12 emus fell. However, Scientific American writes that at that point, the machine gun jammed, and the emus scattered.

Newspapers were soon reporting that "the emus have proved that they are not so stupid as they are usually considered to be." Modern Farmer notes that the emus quickly figured out that the machine guns had a limited range, so "the majority of birds escaped ensuing confrontations with their lives intact."

Strange History writes that one plan involved putting a machine gun on the back of a truck, but "not a single bird was killed, not a single bullet was shot (the gunner had problems enough hanging on) and a stretch of fence was destroyed when the truck [careened] into it."

By November 8, out of the 10,000 rounds of ammunition brought for the mission, 2,500 had been used, with only 200 dead birds to show for it. Plus, in an ironic twist, when the emus ran to avoid the soldiers, even more farmland was destroyed by their powerful legs, according to How Stuff Works.

The army pulls out

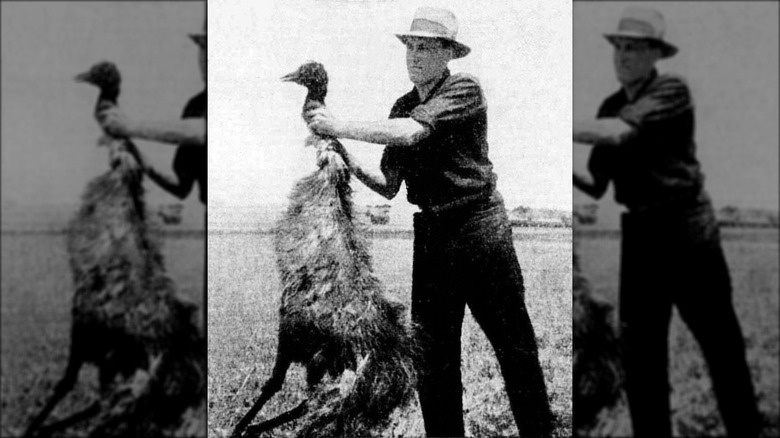

Significantly, Minister of Defense Sir Pearce hadn't informed his superiors of the Emu War, so when Prime Minister Lyons (pictured) was asked about it, he didn't know what to say. According to History Nuggets, the operation turned into "a potential embarrassment," and the soldiers were ordered to withdraw from the Campion district, effectively calling a cease-fire.

Major Meredith, Sergeant McMurray, and Gunner J. O'Halloran complied with their orders, but the farmers pleaded for their return. Sir Pearce was able to finagle a bureaucratic loophole that allowed the Western Australian state government to borrow the machine guns and the soldiers, so, according to Scientific American, Major Meredith mounted a second campaign on November 13, although that day, they only managed to kill 40 emus.

A month later, reports claimed that 100 emus were being killed each week. However, Meredith calculated that they were using 10 bullets for every emu they killed. As a result, on December 10, the soldiers were ordered to withdraw once more, bringing the Emu War to a close.

What were the casualties?

Although there were no casualties on the human side, by the time the bullets were used up by the soldiers, fewer than 1,000 emus had been killed. History Nuggets writes that in his final report, Major Meredith offered a "suspiciously easily divisible number of 986 birds" that were killed using 9,860 rounds of ammunition. He also claimed that 2,500 more had died from wounds, though he didn't indicate how he determined that number.

History of Yesterday writes that it's estimated that the Emu War had "one of the worst bullet-to-kill ratios in military history." After the war, much of the public was also on the side of the emus, having been disgusted by images of the slaughter, such as it was. News of the Emu War even reached Great Britain, where animal conservationists protested the war and "decried the extermination of a rare bird," writes Modern Farmer.

According to "Crocodile Undone" by Marcus Baynes-Rock, the Agricultural Board tried to get the farmers to reimburse them for the cost of ammunition, but the farmers claimed that they were, in fact, owed money since they were the ones slaughtering birds wounded by the machine guns: "It was a farce that cut straight to the weak underbelly of colonialism. It highlighted white Australians' awkwardness in engaging with the land and their hopeless reliance on traditional methods of colonization — militarism, exclusion, and eradication — in the face of a recalcitrant ecology."

Requesting more machine gun crews

Although the Emu War was declared over by the soldiers, with the emus as the victors, farmers found themselves in the same position they'd started out in. Modern Farmer writes that the farmers again asked the government for assistance in 1934, 1943, and 1948. But this time, the military decided not to get involved, and the farmers were told that using machine guns was out of the question.

But according to Scientific American, the government decided that the least they could do was provide ammunition so that the farmers could address the problem themselves. Over the course of six months in 1934 alone, over 57,000 emus were killed.

Between 1945 and 1960, over 284,000 bounties were claimed. Western Australia continued to pay bounties for emus until 1999, when "wild emus came under protection of federal legislation to protect biodiversity," reports The Sydney Morning Herald. In the end, according to Modern Farmer, the only thing that really drove the emus away was "simply scarcity. When the wheat was harvested, the emus moved on."

What happened to the emus and the farmers?

In the 1970s, farmers decided to start farming emus instead of fighting them, and the first farmed emus were created. According to "Crocodile Undone," this began with capturing wild emus and, in ironic juxtaposition, feeding them primarily wheat. By the 1990s, emu farming had caught on in all of the Australian states, and by the mid-1990s, there were over 60,000 emus being farmed in Australia.

With the birds' protected status, the emu population in Australia is estimated to be at least 600,000, and they have been classified as being "of least concern." However, according to Scientific American, wild populations of emus remain "at risk of local extinction due to encroaching human activity."

While it's unclear whether or not the emus remember the Emu War, humans who heard about it found it as entertaining then as they do now. In the end, ornithologist D.L. Serventy summarized the Emu War the best: "The machine-gunners' dreams of point blank fire into serried masses of Emus were soon dissipated. The Emu command had evidently ordered guerrilla tactics, and its unwieldy army soon split up into innumerable small units that made use of the military equipment uneconomic. A crestfallen field force therefore withdrew from the combat area after about a month."