The Disturbing History Of Viruses Escaping From Research Labs

As health officials debate the origin of the COVID-19 virus, one theory has gained renewed attention: the "lab leak hypothesis." As Nature reports, "Most scientists say SARS-CoV-2 probably has a natural origin ... However, a lab leak has not been ruled out." Specifically, the theory goes, that a lab at the Wuhan Institute for Virology, in the city where the first cases were recorded, might be the epicenter for the epidemic.

It is important to note, as Vox explains, that "the vast majority of lab accidents, even serious lab accidents, don't sicken anyone, and none yet has sparked a pandemic in humans." Implicit in that explanation, however, is that lab leaks do happen. More often then you are probably aware. Truly heinous pathogens and poxes have escaped from research facilities and government institutions in countries all over the world — and possibly closer to you than you want to know about.

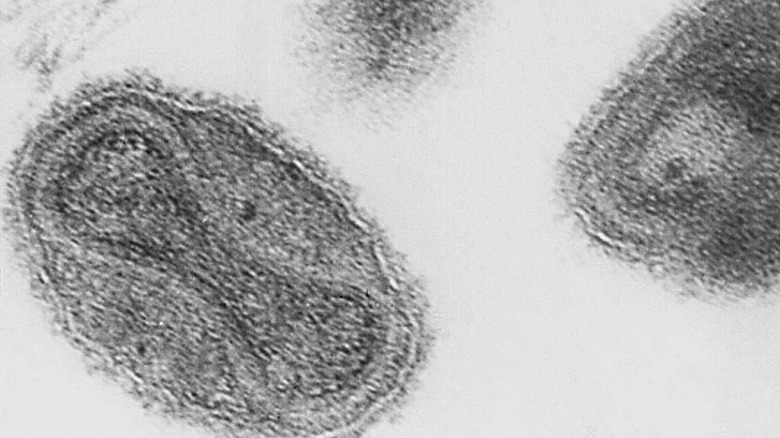

The 1977 influenza pandemic may have started in a lab

The 1918 flu epidemic was the first appearance of the H1N1 virus, also known as swine flu, which lingered around the world for another 40 years, evolving and killing. It seemed to disappear in 1957 only to reappear 20 years later, in China, but first reported by the Soviet Union so the world's press called it the Russian Flu. This pandemic lasted from 1977 to 1978, killing some 700,000 people around the world. A peculiar trait of the virus was that it generally only affected people under 26, which turned out to be because this particular strain of influenza had already circulated the globe in the 1940s and 1950s. This means it was, according to the American Society for Microbiology, "probably not a natural event." That is, someone kept a sample of H1N1 and was sciencing around with it 20 years later. Leading to persistent suspicions that the virus was, as a 2010 article in PLOS One describes, "an accidental release of a frozen laboratory strain into the general population."

This is not the dominant view however. That it could have "accidentally escaped from a research laboratory is formally possible," says Vincent Racaniello, professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, "but there are even less data to support this contention." The professor emphasizes that, "It remains likely that to this date, there has been no real-world example of a laboratory accident that has led to a global epidemic."

Smallpox escaped from British labs 3 times

In 1978, a year after the last recorded natural case and the disease was thought to be eradicated, a woman in the United Kingdom died from smallpox. She was a medical photographer, explains Vox, at the Birmingham Medical School which, because infectious disease stories are just filled with irony, just happened to be in the same building as a research laboratory "where smallpox was studied by scientists who were trying to contribute to the [World Health Organization] eradication effort." Hers was the only fatality. The official inquest said poor ventilation and inadequate safety procedures were at fault.

This wasn't the first accidental release of smallpox in Britain. Four people were infected five years prior when a lab assistant at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine was contaminated during a routine procedure. She survived, but two people died. However, the investigation into the 1978 Birmingham event took a look farther back and revealed that this event wasn't the first either.

The official Report of the Investigation into the Cause of the 1978 Birmingham Smallpox Occurrence reviewed a previous outbreak in the city. Over 70 people in Birmingham contracted smallpox in 1966 from a medical photographer at the school, in the Anatomy Department, who caught it. Even though "The Department of Anatomy is situated on the floor immediately above the virology department," which was conducting experiments with smallpox, nobody thought to investigate the ventilation between the two floors and two labs until 12 years later.

A 1995 encephalitis outbreak may have come from a lab

In the mid-20th century, doctors and scientists in Central and South America were combating a strain of mosquito-borne encephalitis, which usually struck horses and donkeys but would frequently cross over to humans as well. Equine encephalitis causes severe fevers and, according to the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, "can occasionally be fatal or may leave permanent neurological disability (epilepsy, paralysis, or mental retardation) in 4 to 14 percent of clinical cases, particularly those involving children." An animal vaccine was designed and rolled out across the region to protect the horses and mules, and thus the people as well. However, because irony and inadequate vaccine technology, from the '30s to the '70s the "vaccine caused most of the very outbreaks that it was called upon to prevent."

Then in 1995 a massive equine encephalitis flare-up struck Venezuela and Columbia. This strain seemed to be a exact duplicate of a 1963 strain, which is unusual, as viruses in the wild typically keep evolving — it's why you need recurrent flu vaccines. A 2001 paper in the Journal of Virology made it clear that, while they can't definitively rule out natural or other artificial causes, "a far simpler explanation for the complete genomic sequence identity between the ... strains is that the [1995 epidemic] resulted from the laboratory contamination." Almost 100,000 people were infected, over 300 died, and many thousands were left with long-term neurological issues from what may have been a lab accident.

SARS has escaped six different times in three countries

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) first appeared in Guangdong, China, in 2002. The initial outbreak infected over 8,000 people in 29 countries over two years. The virus seemed to tire itself out in 2004, after killing 774 people. "SARS was highly fatal," explains Dr. Jianfeng He, of Guangdong provincial CDC, in the Journal of Thoracic Disease, "with a mortality reaching 10%." However, not all of those patients were technically suffering from the same outbreak.

In the summer of 2003, after five months of no new cases, a research assistant in a Singapore laboratory contracted SARS. He hadn't been working with the disease and, although nobody else got sick and he recovered, reported NewScientist, "sparked a worldwide alert and rattled public health officials who feared that the epidemic had returned." In December, a SARS researcher from a lab in Taiwan tested positive. According to the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, he had been "working without protective gear, such as a gown and gloves." Even though he actually began experiencing symptoms on an airplane, nobody else got sick.

SARS escaped and infected people in China on three separate occasions in 2004. A report from the World Health Organization said that the National Institute of Virology in Beijing was the center of three separate SARS leaks, leading to hundreds of quarantines, dozens infected, and one woman dead. The WHO investigation suggested "biosafety procedures at the Institute" were in need of review.

A U.K. lab released foot and mouth disease

Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD), according to the Mayo Clinic, is "a mild, contagious viral infection common in young children." It's also, however, according to beef and dairy industry journal The Cattle Site, "a severe, highly contagious viral disease of cattle and swine ... [that can] be spread by people, vehicles and other objects that have been contaminated." Because of the extremely contagious nature of the disease, countries that face an outbreak will quickly find themselves subject to export restrictions. And any sign of the virus can lead to whole herds being culled. A 2001 outbreak in the U.K. ended, according to the BBC, with "the slaughter of 6.5 million cattle, sheep and pigs" and a $16 billion economic hit (via Reuters).

After six dormant years, FMD appeared some two miles from the Institute for Animal Health in Pirbright. An investigation ordered by the House of Commons revealed "that the virus had most likely leaked out from drainage pipework at the Pirbright facility, contaminating the surrounding soil and then was carried from the Pirbright site by vehicles." The Pirbright lab is a Bio Safety Level 4 lab, the highest level, and mud on a car driving through it caused a panic that saw hundreds of animals put down and the British beef industry suffered a major loss.

A New York research lab had several accidents

FMD is considered so dangerous that, according to trade publication The Angus Journal, a series of outbreaks in Canada and Mexico scared the U.S. government into building a dedicated research facility. Originally built on an island near Long Island, "accessible only by ferry and helicopter," the Plum Island Animal Disease Center now studies all manner of other infectious monsters as well but, says the Department of Homeland Security, remains "the only laboratory in the nation that can work on live FMD virus."

However, partly because of its isolation, Plum Island has also been the center of a number of urban legends. There is a "misconception ...," said a Plum Island researcher to New York's NBC4, "that we work on secrets and that our research is secret," leading to conspiracy theories that Lyme disease was created there by Nazi scientists as a bio-weapon or that the government created new animals with genetic experiments (that washed up on a Long Island beach.)

If there is anything scary about the Plum Island facility, it could be that it has experienced accident after accident for basically its entire existence. Congress ordered an investigation into the facility in 2008 after the U.K. leak the previous year. According to NBC News, not only had FMD been released from the facility at least once in 1978, but the report revealed "several accidents" going all the way back to 1954, the year it was built.

Four lab workers in Virginia contracted Ebola

Ebola frequently ranks among the scariest diseases humans have ever encountered and with good reason. According to WHO, Ebola is literally one of the deadliest viruses on Earth with "case fatality rates ... from 25% to 90% in past outbreaks." Meaning a 50% fatality rate — half of everyone who gets Ebola dies from it. Since its discovery in 1976, says the global charity Mercy Corps, Ebola has been found in 18 different countries, including the United States, although the vast majority are in Africa, where it was first diagnosed.

The virus first appeared in the U.S. in 1989, reports CBS News, at a private primate quarantine facility in Reston, Virginia. After dozens of research monkeys imported from the Philippines died suddenly, they were discovered to have a highly virulent breed of Ebola, the Zaire strain, with a 90% fatality rate. Four workers at the facility tested positive for Ebola soon after. Luckily for them, the workers contracted what is now known as Ebola-Reston, "the only one of the five forms of Ebola not harmful to humans."

Ebola-Reston returned seven years later, again via monkeys from the Philippines, this time imported by a company in Texas. One monkey died from the disease, but another 49 were euthanized so as to prevent its spread among the other animals under quarantine, notes the CDC. Which is kind of the exact purpose of quarantine so the virus never spread out of that unit, and no other animals nor any humans were infected.

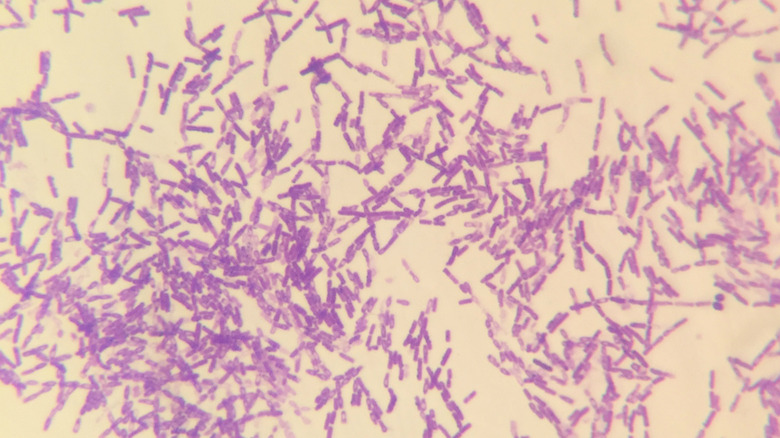

A secret Soviet facility released anthrax on accident

Anthrax is a bacteria, "found naturally," according to the CDC, "in soil and commonly affects domestic and wild animals around the world." It can also affect humans, says the FDA, in one of three ways, with varying levels of fatality: "approximately 20% for cutaneous anthrax ... 25-75% for gastrointestinal; inhalation anthrax has a fatality rate that is 80% or higher."

The lethality of anthrax led to it being studied for years as a biological weapon. It was used to deadly effect in, what the FBI called, "the worst biological attacks in U.S. history" when five people were killed by letters laced with anthrax spores in 2001. Anthrax was actually first used as a weapon during World War I, according to the CDC, and has been subject to decades of offensive research by multiple nations afterwards. Finally, after "growing international concern about the use of bioweapons," over 100 countries signed a treaty in 1972 banning the "development, possession, and stockpiling of pathogens or toxins ... [and] required parties to destroy stockpiles of bioweapons within 9 months of signing."

Seven years later, reported Science, "the deadliest human outbreak of inhalation anthrax ever" killed at least 66 people in the Soviet Union, supposedly due to contaminated meat. After the Cold War, and the collapse of the USSR, it was discovered that the outbreak was caused by an accident at a secret illegal weapons facility. — "50-kilometer trail of disease and death" in what some now call a "biological Chernobyl."

There were three accidents with two deadly viruses in one Russian lab

The Vektor State Research Centre of Virology and Biotechnology is deep in Siberian Russia and houses, according to Vox, "one of the largest collections of dangerous viruses anywhere in the world." It is, in fact, the only other place in the world beside the CDC in Atlanta permitted to store smallpox. It joins Ebola, Marburg, anthrax, and other terrifying bugs at Vektor, where researchers trawl through their genetic codes for defenses against them. Some of which have escaped. Multiple times.

Between 1988 and 2004, reports the Sydney Morning Herald, there were three separate lab accidents at Vektor. The first was a researcher who "accidentally contracted the Marburg virus and died in 1988, while another worker contracted the same virus and survived" two years later. In 2004, another Vektor researcher died after pricking herself with Ebola. In none of those cases did the diseases ever actually escape the lab or infect anyone other than the initial case.

Then, at the tail end of 2019, as if to soften us up for COVID, the research center exploded. With an irony lost on no one, the Vektor labs were being renovated, reported Vox, "when a gas bottle exploded, sparking a 30-square-meter fire." A Vektor spokesperson told the Russian media that no dangerous diseases were actually stored in the destroyed room. However, as Vox reminds, "Russian public reports on safety incidents are not always accurate."

University of North Carolina keeps losing infected test mice

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is one of the largest health sciences research institutions in the country. "The National Institutes of Health [NIH]," says the university website, "is UNC's largest federal funder," responsible for not only nearly $500 million in annual funding but also for overseeing much of the research done at UNC. Which is why, according to records secured by ProPublica, when UNC researchers screw up, they have to report it to the NIH. And it turns out there was a lot to report.

UNC at Chapel Hill misplaced lab mice on at least eight occasions in 2013 and 2014, several of which were infected with H1N1 or SARS. "Due to the inbred nature of the mice," says USA Today, "their behavior varies wildly," and UNC insisted that, since "lab staff handled mice roughly 54,000 times" a year, mice only escape "about 0.001%" of the time. Between 2015 and 2020, ProPublica revealed, there were another "28 lab incidents involving genetically engineered organisms." Mice escaped, liquids were spilled, and, at least twice, mice bit through the gloves of the researchers handling them. "UNC declined to answer questions about the incidents," said ProPublica, "contrary to NIH guidelines," but NIH officials did tell them that at least six of the incidents involved "SARS-associated Coronavirus." And the most recent one, in mid-2020, was a modified "strain of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19."

Over 6,000 people got sick in China from a lab release

The bacterial disease brucellosis, discovered "in the late Roman era," according to the journal Tropical Medicine and Infectious Diseases, "is one of the most common contagious ...zoonotic diseases with high rates of morbidity and lifetime sterility." This bug kills a lot of animals. It can infect humans as well but, while the Minnesota Department of Health says such cases are extremely rare and "rarely fatal," the Mayo Clinic warns that "Brucellosis can affect almost any part of your body, including your reproductive system, liver, heart and central nervous system," leaving survivors with complications ranging from arthritis to meningitis to testicular infections and inflammations.

Over 6,000 people in northwestern China contracted brucellosis in 2020 and, according to reports in China state media Global Times (via Reuters), the government ended up testing 55,000 people in the remote Gansu province. Other disease-related things were also happening in China, and the whole world, during 2020 so the story wasn't widely reported. According to the Global Times, "the outbreak originated at a biopharmaceutical factory owned by China Animal Husbandry Industry Co.," which was manufacturing — ironically or predictably – brucellosis vaccines. The company improperly disposed of the remnant bacteria used to make the vaccines, which got carried to a veterinary research institute, where the first cases were recorded. The vaccine production factory was closed down and dismantled.

A dangerous bacteria escapes from a Louisiana lab

The Tulane National Primate Research Center in Louisiana is part of a network of seven primate research facilities in the U.S., according to the New Orleans Advocate, researching infectious diseases and "devising ways to counter potential bioterrorism threats." Among the nightmares they keep on the shelves for study are Ricin, HIV, tuberculosis, and a nasty little bacterium called Burkholderia pseudomallei. Burkholderia effects both humans and animals, has a varying mortality rate, and, says the Center for Health Security, because it's easy to collect, easy to "engineer strains that are resistant to multiple antibiotics," and has no vaccine, that "several countries have studied B. pseudomallei for use as a bioweapon."

The USDA and CDC both launched full-scale investigations into the Tulane Center when this dangerous bacteria escaped in 2015. Even though the lab where research is performed on Burkholderia is, as Tulane officials described it to USA Today, a "box-within-a-box within a box," it somehow escaped, and several research monkeys and staff at the facility contracted Burkholderia. The disease-causing bacteria clings easy to surfaces and travels with moisture easily. Investigators concluded, reports the AP (per Arkansas Online), that "the most likely cause" of the breach was staff carrying the bacteria on their shoes and scrubs between labs.