Stories From History That Sound Fake But Are Completely Real

Math and science might be governed by a set of rules, constants, and unchangeable truths, but there are no such restrictions on human behavior. That's a good thing — it's led to instances of incredible ingenuity and the development of inventions that have changed the course of history, but it's also led to a lot of really weird stuff.

Humans, it turns out, are bound by nothing but imagination, while things like common sense take a back seat. There's no limit to the sorts of antics and shenanigans that people will get up to, and here's the thing: You can't make this stuff up, because if any of these stories plucked from history showed up in a Netflix series or the next big-screen blockbuster, social media would be all up in arms, claiming it's too improbable to be the least bit believable.

But they're all true — every single one of them. From the town that worked together to get away with murder to the man who just wouldn't die, they're all collective proof that history is a super weird place, humans are strange, and the truth? That's definitely stranger than fiction.

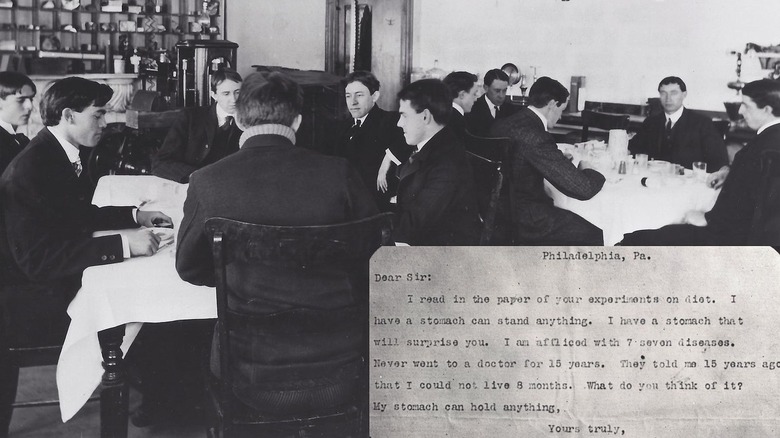

When 12 men poisoned themselves for the good of the country

At the turn of the 20th century, food manufacturers could use pretty much anything in their products, and it was absolutely fine. (We're looking at you, Coca-Cola.) But one Purdue scientist named Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley decided that things were getting out of hand and petitioned Congress for permission (and a grant) to carry out testing on the effects common food additives had on the human body.

That, says Esquire, was a sanitized version of what he was doing. Wiley already knew additives were dangerous; he just needed to prove it. So, he assembled a group of 12 volunteers — all male, all young, and all healthy — who signed waivers promising not to sue him if they got sick or died. And that was important, because they were all eating deadly additives.

They started in 1902 with borax, which was used as a preservative at the time. Predictably, it wasn't long before all the men given the poisons were sick. (The Indiana History Blog notes that the 12 were split into groups of six, with neither group sure if they were the control or if they were being poisoned.) With borax out of the way, they moved on to eating sulfuric acid, sodium benzoate, formaldehyde, copper sulfate, saccharin, and saltpeter, among other things.

By 1906, Wiley's volunteers had demonstrated the need for food regulation, and Congress passed both the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act.

The Romans used nanotechnology

Nanotechnology is one of those things that, even in the 21st century, is still kind of in the realm of science fiction ... at least, for most of us. Sure, it exists, but how the heck does it work? Who knows! It might as well be magic, right? Weirdly, modern man isn't the first to unlock the secrets of nanotechnology, and according to Interesting Engineering, that honor goes back to the ancient Romans.

The Lycurgus Cup is called such because the figures are depicting the story of the death of King Lycurgus, who was driven mad by Dionysus. It's a cool story, but even cooler is that the cup is usually green, until the light shines through it. Then, the scenes turn bright red.

In 1958, the cup was donated to the British Museum, and it was another nearly four decades before researchers figured out how it had been made. The glass, it turned out, had been made with silver and gold that was ground down to individual particles that Smithsonian Magazine says are "less than one-thousandth the size of a grain of table salt." The color change comes when light reflects off the tiny flakes, making them vibrate and turn different colors.

It wasn't an accident, either. The precise work that needed to go into the cup suggests that even if they didn't know the exact science behind the principle, the Romans knew exactly how to make some wild, color-changing nanotechnology way back in the fourth century A.D.

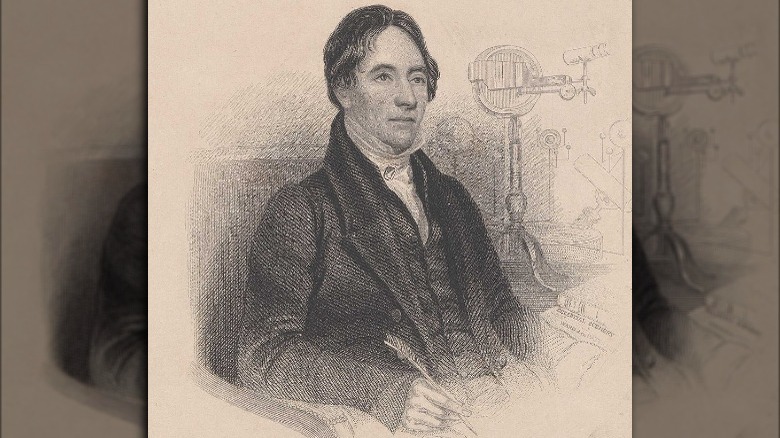

A Victorian-era astronomer wanted to build a massive signaling device to contact aliens

Aliens might seem like the domain of 1990s-era TV shows and modern conspiracy theories, but the belief that we're not alone goes back a long way. In 1837, one scientist hatched a plan to let them know we're here.

Scottish astronomer, philosopher, and church minister Thomas Dick played a crucial role in getting 19th-century theologians and scientists to at least be all right with the idea that science and religion could coexist, says Undiscovered Scotland. He also promoted a wacky idea: Our solar system, he said, was home to roughly 22 trillion other beings.

He came up with that number with some impressive science that took the average population of England and expanded that to cover the entire solar system. From all the planets to even asteroids, if everywhere supported the same density of life as England, that's how many aliens would be in our backyard.

Wired says he took it one step further, too. In the 1830s, he wanted to get in touch with the 4.2 billion aliens he thought were living on the Moon. In order to do so, he proposed building "a huge triangle or ellipsis of many miles in extent, in Siberia or any other country." The idea was that even if the aliens didn't have telescopes, they'd have been able to see that and know we were here. Sadly, it didn't happen.

The most dangerous occupation in Glasgow was once being an ice cream man

It doesn't matter how old you are, there's a certain amount of childlike glee and excitement that comes with the familiar song of the ice cream man. The promise of a cold, creamy treat on a hot summer day is enough to send anyone running, but anyone in Glasgow during the 1970s and 1980s might get something completely different.

In short: heroin and bullets.

According to Atlas Obscura, the ice cream men of Glasgow spent decades dealing in things like stolen merchandise and drugs, all under the colorful cover of ice cream. Being an ice cream man could very quickly turn deadly: Territories were staked out, and anyone caught selling in someone else's turf might catch an ax to the face.

It was serious, gang-level stuff, and that particularly dark part of Glasgow's history is popularly known as the Ice Cream Wars. It's filled with terrifying incidents, like one in 1979 when territory disputes escalated into mob violence. What started out as a necessary service — ice cream men sold essentials like toilet paper and groceries to people in low-income housing without store access — turned into selling more illegal things, which were protected by armed gangs that made sure no one was selling on their territory. And yes, people absolutely died in the crossfire.

Eventually, the Ice Cream Wars ended simply because they were no longer the money-making vans they once were.

The medieval devout had a thing for X-rated adornments

Look closely at a number of medieval paintings, and you'll see something odd: Many of the people depicted seem to be wearing pins or amulets depicting male or female genitalia. Those crazy artists, always sneaking in secret imagery!

Only, according to Medieval Badges, it's not just secret imagery. A shocking number of the actual badges have been discovered, and they're wildly imaginative. Some show men and women in positions that might be described as "advertising their goods," while many others are Monty Python-esque depictions of things like winged phalluses or vulvas on horseback. What the literal heck, medieval people?

Ben Reiss of National Museums, Scotland says that not much research had historically been done on these X-rated images until the 1990s. Then, it was suggested that the amulets were probably meant to be good luck charms, but more research found medieval texts mentioning the badges in the context of identifying those on religious pilgrimages.

The more digging they did, the more they found that the Church has more than their fair share of sexually explicit imagery — it's so common that there's a name for it: Sheela-na-gig. They serve more as a commentary on morality than as some X-rated entertainment, and it's shown scholars that sexually explicit and the devoutly religious haven't always been mutually exclusive.

The body of a Wild West outlaw ended up as a prop in a California fun house

According to the Library of Congress, Elmer McCurdy spent his life as a drifter attached — briefly — to a group of train robbers who really weren't all that great at what they did. After a 1911 heist yielded just $45, some whiskey, and a tail from Johnny Law, McCurdy was killed in a shootout.

That definitely should have been the end of him ... but it wasn't. McCurdy was embalmed, but when no one came to claim his body, he simply sat. It wasn't long before it became clear that the embalmer had done such a good job that the outlaw wasn't decaying.

McCurdy — who was now being advertised by the funeral home as "the Embalmed Bandit" — was then taken to the sort of sideshow that could only exist in the early 20th century. From there, he changed hands a few times, and his story took an even more morbid turn when, in 1968, he got mixed up with not-at-all-real wax figures, sold to a funhouse, and hanged from the ride's gallows.

And that's where he stayed for eight years, until a crew member there filming for "The Six Million Dollar Man" accidentally broke McCurdy's arm, and everyone realized there was real bone in there. McCurdy was given a plot in Guthrie, Oklahoma's, Summit View Cemetery, and he was finally allowed to rest in peace ... 66 years after his death.

Sightings of the Loch Ness monster are incredibly ancient

Everyone's heard the story that there's something prehistoric living in the depths of Scotland's Loch Ness, and there've been plenty of stories touted as "proof," including that incredibly famous, incredibly debunked photo that's been circulating for years. Textual, historical evidence that people have been reporting Nessie sightings for centuries absolutely sounds like something that's 100% made-up, but it's out there.

Colum Cille was the grandson of the Irish king Niall, and he was born in 521. As Historic UK says, he's generally credited with bringing Christianity to Scotland when he settled on the Isle of Iona in 563 and built a community where dozens of kings were subsequently buried.

Two years after reaching Scotland, he was doing his traveling missionary thing. He reached Loch Ness on August 22, 565, and there, according to The Scotsman, he saw a man swimming in the lake, with a monstrous creature right behind him. The monk, later known as St. Columba, supposedly invoked the name of God and sent the monster diving back into the depths of the lake, making it the first sighting of the Loch Ness Monster.

Admittedly, there's some debate about the story, considering that it was written about a century after Columba supposedly got all monster-tamer on the shores of Loch Ness — but that still makes the belief in Nessie a shockingly old one.

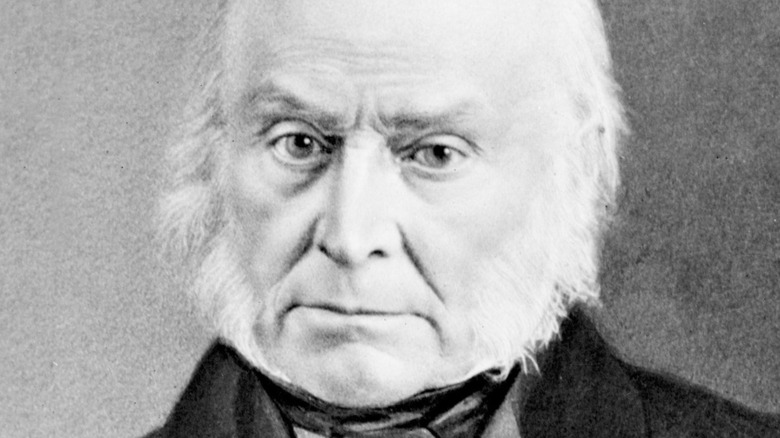

A U.S. president once approved a journey to the center of the Earth

While it hasn't quite picked up the same kind of momentum as the flat Earth theory, the idea that Earth is actually hollow is a perfectly legit alternative. It's not exactly new, and strangely, there was a U.S. president who wasn't just a believer but gave the go-ahead on an expedition to prove the theory was true.

It was the 1820s, and hollow Earther and Army captain John Cleves Symmes wanted everyone to know that the planet's crust was around 800 miles thick, and there were entrances at both the poles. He described going into these entrances as just like walking along into the center of a giant donut: You could, in theory, stroll right in and find yourself in an interior world similar to our surface world (via the Northern Kentucky Tribune), except, presumably, darker.

Along the way, says io9, he went right to Congress to try to get approval to launch a government-funded trip to prove just how hollow the Earth was, and while Congress declined, John Quincy Adams was all in favor of it.

Unfortunately, the expedition never got off the ground. Symmes died in 1829, and most of the people who had heard his claims thought they were pretty ridiculous. Adams ended up being a one-term president, and although the government did fund an 1838 expedition to the North Pole, it had nothing to do with the hollow Earth theory.

The woman who gave birth to rabbits

It's biologically impossible for a woman to give birth to rabbits, yet it absolutely happened ... sort of.

It was London in 1726. On 17 separate occasions, a poor woman named Mary Toft went into labor and, instead of spitting out a bouncing baby boy or girl, some baby rabbits came out of a place where rabbits should never, ever be.

There's a lot more to the story, and it started on September 27. That's when Toft "gave birth" to what doctors were able to identify as (via Atlas Obscura) "three legs of a Cat of a Tabby Colour, one leg of a Rabbet: the guts were as a Cat's and in them were three pieces of the Back-Bone of an Eel."

When doctors came from all across the country to study the woman who seemingly gave birth to her 15th rabbit in November, things started to not make sense. (Well, more than they already made no sense.) Some of the rabbits were as old as three months, and it eventually came to light that assistants were inserting animals inside her, where they'd stay until they were expelled by her body.

What followed was chaos: Toft was branded as a liar, and the doctors she'd fooled were ridiculed. But today, historians think it wasn't her idea at all and that it's entirely possible she was a poor, desperate woman manipulated into doing horrible, painful, dangerous things. No one knows why she did it, but it absolutely happened.

The man they couldn't kill

In 1932, three friends — Francis Pasqua (right), Tony Marino (left), and Daniel Kriesberg — hit upon an idea: They'd take out an insurance policy on someone, name themselves as beneficiaries, and then kill him. The man they picked was an Irishman named Michael Malloy. He was a loner, had no friends, and already drank a lot, so how hard would it be to kill him? They were going to find out.

Smithsonian Magazine says that once they'd taken out three separate policies, they got to work. They started by giving Malloy an open tab at Marino's bar, which he quickly started to take advantage of. Like, a lot. For days. When regular alcohol didn't do the trick, they started giving him wood alcohol. That should have been deadly, but it didn't kill Michael Malloy.

This went on for so long that what they were spending on alcohol was quickly approaching what the insurance policies were going to pay out, so they escalated things. They gave Malloy bad oysters, fed him sandwiches made with shards of metal, dumped him — naked and wet — into a snowbank, and even hit him with a car and then backed over him. He just kept showing up back at the bar.

This went on for seven months until Malloy finally died. A tube had been forced down his throat and connected to a gas line, and by this time, the law was suspicious. After receiving just a couple hundred bucks, the three were arrested, tried for first-degree murder, and executed at Sing Sing.

When women had to apply for permits to wear pants

The idea of applying for a permit to wear certain items of pretty ordinary clothing seems nuts, but that's exactly what happened in 19th-century Paris.

Starting on November 7, 1800, Wonders & Marvels says that any woman who wanted to wear pants needed to apply for a permit — and get authorization from the appropriate government officials — or wait to be arrested. Why? Apparently, pants-wearing women were a danger to themselves and everyone around them.

And women absolutely followed the letter of the law. Record-keeping being what it was, it's not clear how many got permits, but we do know of people like Catherine-Marguerite Mayer. She was issued the first permit six years after the law went into effect and was given an exemption so she could ride a horse. Although most permits were said to be issued in cases of "health requirements," some women — like printers, journalists, and other women in traditionally male-only professions — were allowed to wear pants for their jobs. Permits also needed to be renewed: The artist Rosa Bonheur had a permit, but it was only good for six months.

However long it seems like the law stayed on the books, the truth is that it was around for much longer than that: According to the BBC, it was only formally overturned in 2013.

Boston was once knee-deep in molasses

Floods are terrible, but a flood of molasses? That's even worse, and it's not the prequel to "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory." It really happened, back in Boston in 1919 — although the aftereffects of the disaster lasted well past that date. According to History, some areas smelled like molasses for decades after the cleanup, and as for the legal fallout? That wasn't settled until 1925 (via History Today).

What happened was as awful as it was bizarre. On January 15, a molasses storage tank standing along the waterfront burst, spilling 2.5 million gallons of molasses in a 15-foot-tall wave that moved at 35 mph.

Eyewitness accounts are terrifying: Buildings fell, telephone poles snapped, electrical wires flew, steel girders broke, and people drowned. An entire section of the city was destroyed, and none of Boston was untouched: Even parts that avoided being drowned in molasses were sticky as people carried the goop on their clothes and shoes.

Cleanup took a whopping 87,000 man-hours, and the flood did an amount of damage that, in today's money, would cost around $100 million. The 119 lawsuits that followed included 25,000 pages of transcripts and almost 2,000 exhibits, and at the end of it all, the company that owned the tank was found responsible. The tank — which had leaked so badly that locals filled cups with dripping molasses — was fundamentally structurally flawed, and it had cost 21 lives.

The entire town that was in on a bully's murder

Surely, the entire town that was a witness to a bully's murder and kept quiet about it for decades was the plot of a Netflix crime drama, right? Maybe ... but it's also the story of Skidmore, Missouri.

First, let's explain how the town got to this point. Ken McElroy was born in 1934, and he was a terrible person. No, really, says Patch – he was just awful. His list of offenses include (but aren't limited to) arson, burglary, statutory rape, child molestation, assault, threatening to kill his neighbors, stealing livestock, harassing women, and destroying property. The New York Times says his own lawyer estimated that he averaged about three felony charges a year for years, but no convictions ever stuck — even when he shot and killed the town's 70-year-old grocer, Ernst Bowenkamp.

That murder happened in 1980, and on July 10, 1981, McElroy walked out of the local tavern in broad daylight, got into his truck, and was shot and killed.

It's estimated that dozens of people — at least — saw the killing but presented investigators with a united front and gave up nothing. Cheryl Huston — the daughter of Ernst Bowenkamp — saw it, too, and later told the Times, "We were so bitter and so angry at the law letting us down that it came to somebody taking matters into their own hands. No one has any idea what a nightmare we lived."

The case was never solved.

The nannies abandoned in London

To say that Britain's actions in their colonial territories were less than stellar examples of how to be good overlords is a massive understatement, and some of the tales to come out of that era seem too terrible to be true. But they are — including the story of the mass abandonment of women hired as nannies.

They were called ayahs, and the term came to refer to anyone — originally those from India but eventually those from other colonial outposts — who was hired to care for the children of wealthy British families. They were responsible for every aspect of childcare, and when the families decided it was time to go home, Atlas Obscura says many took their ayahs with them. But once the long, arduous, stressful journey was over, they abandoned them.

According to The Guardian, most ayahs were listed as the property of the families who hired them and were discarded like extra pieces of carry-on luggage that were no longer needed. There are no concrete records of how many women were simply left — often standing at the train station or at the ports — but it's estimated there were thousands.

There were so many that Christian missionaries set up the Ayah's Home in East London to try to help some of the women. Most of their lives went undocumented and unrecorded — many were called by their employers' names in what few records there are — and they're now largely forgotten save for a handful of photos.

New York's mayor once fought organized crime with an artichoke ban

How does a mayor take on New York City's organized crime? Ban artichokes!

That's not the punchline of a really strange joke, and it actually happened. The mayor in question was Fiorello LaGuardia (left), and on December 21, 1935, he banned artichokes because, he said (via Atlas Obscura), they were a "serious and threatening emergency to the city."

Let's back up. Artichokes were incredibly popular among Italian immigrants, who could only get this fair-weather crop from West Coast farmers — which is where the mob came in. One of the mafia's major money-makers was the agricultural industry, and by the time LaGuardia decided it was time to outlaw artichokes, the mafia had been collecting millions. It was money that came first when they started charging growers to import their product, and it wasn't long before the "transportation racket" escalated. Wholesalers and vendors were buying at massive markups that went right into mob pockets, and let's put it this way: Ciro Terranova's nickname was the "Artichoke King."

Artichokes weren't the first or the last time the mob used agriculture as a money-making machine, but LaGuardia's ban hurt. A lot — LaGuardia only needed to keep the ban in place for three days. It ended up lifting the mob pressure on the crop and made artichokes much more popular outside of the Italian-American community. Who would have thought?

Mummies are yummy!

Here's a fun little tidbit to bring up the next time Janice from Accounting starts going on about how all-natural foods are better: They definitely thought so in the 16th century, and people were totally down with eating some all-natural mummy in an attempt to cure what ailed them.

The Science History Institute says that how we got there is complicated and likely started with bitumen. It's another word for asphalt, and while it's been used in construction for a long time, it was also medicinal ... sort of, as it was used for things like making casts and setting bones. Ancient Romans advocated for eating it, too, to cure things like dysentery.

Fast-forward to Europe's discovery of Egyptian mummies and the belief that the black stuff coating most of those mummies was bitumen. See where this is going?

A bitumen shortage forced desperate Europeans to look elsewhere for their medicinal asphalt, and that elsewhere was mummies — especially after a 12th-century translator equated bitumen with mummy goop. Eating mummy became part of the widespread practice of "corpse medicine," which is exactly what it sounded like. Not only were people eating mummy (which was available in powdered form or by the whole body part), but they were eating powders derived from "the unburied skulls of three men who died a violent death" as a cure for epilepsy. Medicine has come a long way since then.