Unique Funeral Customs From Around The World

There's no easy way to say goodbye to loved ones. In the Western world, the focus is primarily on having a memorial service or funeral. In both cases, guests pay their respects and honor the memory of the deceased. Beyond that, there are two ways most individuals deal with the disposal of their loved one's remains: burial or cremation. Sure, innovative and creative ways to deal with cremains abound, from sending ashes into space to planting them at the bottom of the ocean to encourage coral reef growth. But the basic concept remains the same: giving your loved one an appropriate sendoff.

In other parts of the world, however, you'll find significant differences when it comes to how family and friends are laid to rest. Various factors impact last rites and burial practices, including religious beliefs, societal status, cultural norms, and even practical considerations such as the land available for cemeteries. But these represent just the beginning when it comes to how people deal with death and the loss of loved ones. From age-old traditions to state-of-the-art techniques, keep reading as we explore fascinating funerary customs.

Some Taiwanese funeral celebrations include strippers

Remember the old saying, "Party like it's 1999?" A more apt phrase might be "party like a Taiwanese funeral." Costing tens of thousands of dollars, funerals in Taiwan can feature everything from professional mourners to exotic dancers who perform provocatively at the graveside of the deceased. How did blaring music, strobe lights, and scantily clad women become a part of some Chinese funerals? According to the BBC, explanations include the desire to attract large crowds, which represents a sign of honor. What's more, many families in China and Taiwan see funerals as a way to display their disposable wealth. And the money spending doesn't stop with exotic dancers.

If you have the chance to attend one of these over-the-top events, you may also see singers, comedians, and actors. The custom of entertaining the bereaved proves common in rural China. But you'll see this custom practiced even more widely in Taiwan. One reason for this? The Chinese government's continued crackdown on funerary strippers, deemed "vulgar and obscene."

Despite China's disparaging perception of these festivities, many prominent figures continue to spend big on family funerals. One of the most extravagant memorials in recent memory occurred in January 2017 as detailed by QZ. When 76-year-old political figure Tung Hsiang passed away in Taiwan, his family staged a memorial celebration of epic proportion. Hsiang requested a "hilarious" going away, and his son obliged, organizing an event that showcased giant puppets and 50 pole dancers.

Some Papua New Guineans smoke the corpses of their deceased

The Änga clan of Papua New Guinea's Menyamya region remains steeped in millennia of tradition. Insulated by rugged terrain from the modern world, they live as their ancestors have for generations. Among the many practices they still honor: Preserving the bodies of the deceased through the practice of smoking.

How did the inhabitants of Änga villages such as Watama and Aseki become involved in the process? The origins remain shrouded in mystery and speculation. As reported by the BBC, some locals claim the custom started roughly around World War I and continued until 1949, when missionaries came to dominate Papua New Guinean religious life. But Live Science presents a different picture, highlighting the mummy of one prominent Änga leader, Moimango, smoked and mummified following his death in the 1950s.

Although we may never understand what inspired the Änga to begin this practice, we know what happens to the bodies following a minimum of 30 days of smoking in a hut. Remains get displayed in bamboo cages located on clifftops visible from local villages. Keeping an open line of sight remains critical to the Änga, who perceive the spirit presence of an ancestor by seeing their face, even after death. What's more, they believe that the bodies of exceptional individuals must be cared for after death to keep the deceased from roaming the locale, causing problems with crops and hunts.

The fascinating story behind South Korean death beads

As reported by CBC, South Korea has a severe lack of space when it comes to burials. The problem proves so acute that the government enacted a law in 2000 stipulating that the final remains of loved ones get exhumed and moved after 60 years. The government also actively promotes the cremation of dead loved ones. Since 2010 alone, nearly 70% of all South Koreans who pass away now get cremated, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Now, some families have taken this next level by transforming the ashes of loved ones into colorful gem-like bead keepsakes. Individuals attracted to this unique solution realize burial is no longer a long-term solution in South Korea. But they may not feel comfortable with keeping a drab and somber urn around. For this reason, death beads offer the preferable solution. Not only does the finished product have a beautiful appearance, but the beads represent an accessible keepsake of a beloved family member. That said, families may choose to bury the death beads or dispose of them in another way.

Who produces death beads? According to Time Magazine, Bonhyang, a company founded and overseen by creator and CEO Bae Jae-yul. The term Bonhyang translates as "returning to one's homeland." And according to Bae's wife and business partner, Hong Yang-ja, the company has changed her perceptions of death. Instead of thinking of it as something to be dreaded or feared, she now sees it as a natural process.

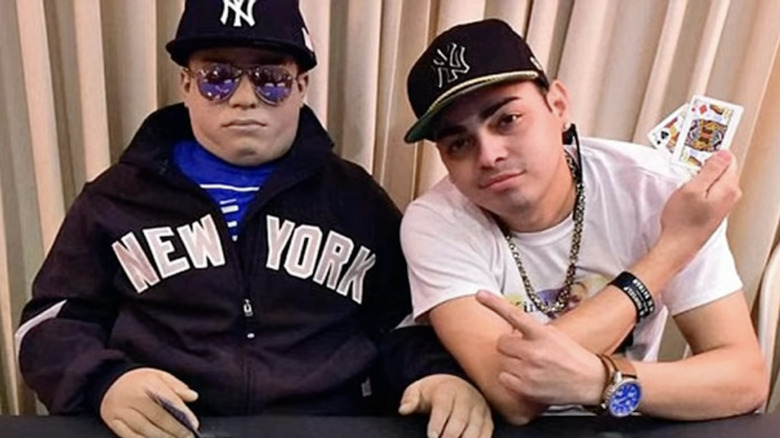

Extreme embalming on the rise in New Orleans

A new trend known as extreme embalming continues to make headlines, especially in places like New Orleans and Puerto Rico, where the deceased get propped up in lifelike poses to attend their own funerals. While most mortuaries steer clear of this treatment of the dead, a few brave funeral homes are making leaps and bounds when it comes to posing corpses for final viewings.

Extreme embalming requires an entirely new approach to embalming a person, according to ABC News. For example, it involves the use of much firmer fluids to maintain lifelike poses. These poses may range from standing to sitting, or even action poses. The practice started in Puerto Rico in 2014 when Christopher Rivera, a local boxer, first got propped up in a fake ring. As reported by tabloid the Daily Mail, the practice reached new artistic heights with the treatment of the body of David Morales, displayed riding one of his beloved motorcycles.

How do funeral homes decide which poses will best suit the deceased? They focus on themes related to the passions or professions of those who have passed. They also try to find ways to surround the individual with the things they loved in life. In some cases, this may include everything from posing an individual so they appear to be playing video games or driving a taxi (depending on their vocation). These nontraditional embalming methods are rewriting how some individuals choose to remember loved ones.

Ghana wins when it comes to so-called fantasy coffins

For the past six decades, the fantasy coffins of Ghana have both fascinated and amazed people worldwide with their intricate details and imaginative subject matter (via CNN). The coffins reflect the passions of the deceased and include everything from cars to beer bottles, seashells to lions. According to Paa Joe (a.k.a. Joseph Ashong), Ghana's most famed fantasy coffin maker, fashioning these whimsical final vessels proves a big business in Ghana and other parts of the world.

In the trade for half a century, Joe started in 1962 when his mother sent him to apprentice with his uncle in the coffin trade. Joe was just 15 at the time. By 1974, he completed the apprenticeship and launched his own business. He charges local customers approximately $1,000, but prices depend on the materials he uses and how detailed the final product may be. For international customers, Joe uses tiptop materials. These include high-grade hardwood such as mahogany. As a result, prices for coffins sent around the world range from $5,000 to $15,000 or more per coffin.

Most fantasy coffin makers complete between seven and eight masterpieces each month. But as Ghana's mortality rates have decreased in recent years, Joe has fewer apprentices than he did a few decades earlier. Nevertheless, he maintains that business is quite good, noting it's a "very profitable" enterprise.

Exhuming the deceased for lively celebrations

Every seven years or so, CNN reports that the Malagasy of Madagascar exhume the bodies of the dead from ancestral crypts for a celebration known as famadihana. Activities include drinking, dancing with the bodies, and rewrapping them in fresh cloth before re-interring them face down. Think of the festivities like a family reunion where the deceased take center stage.

During this sacred ritual, the dead get removed from their ancestral crypts to be spruced up. After carefully removing the clothes relatives got buried in, the New York Times reports that family members dance with the corpses before rewrapping their ancestors' bodies in silk. The day filled with music, merriment, and honoring the dead, ends at sunset. That's when corpses get reinterred laying facedown. After all, famadihana translates as the "turning of the bones."

Why do the Malagasy observe this ritual? Because they believe that their deceased family members act as intercessors between the living and the divine. In other words, by taking care of their ancestors as the flesh decomposes from their bones, they hope these dead relatives will return the favor in the spiritual realm.

Tibetan sky burials are all for the birds

According to Atlas Obscura, Vajrayana Buddhists see human corpses as nothing more than empty vessels. As a result, Tibetans have a unique burial custom, known as a sky burial. As reported by Anthropological Perspectives on Death, when a family member dies, the body is taken to a high elevation, where a Burial Master cuts up the remains of the deceased, and the pieces are then left for vultures to devour.

These sky burials (a.k.a. celestial burials) predominate atop mountains in Tibet and Mongolia. Said to have been practiced for up to 11,000 years, this means of disposing of corpses serves an essential purpose. Locals believe that the vultures who consume body parts transport the bodies into the heavens. There, the souls of the deceased will stay until it's time for them to reincarnate.

Despite this spiritual explanation to the custom, the ritual also comes with a practical application. Because of Tibet's cold climate, the ground often proves frozen, making a standard burial difficult, if not impossible. Instead of attempting to dig into the icy ground, sky burials represent a practical and attractive solution for disposing of dead bodies. What's more, since the people of Tibet and Mongolia believe the soul immediately leaves the body after death, they see the rapid disposal of the physical body as integral to an easier and quicker reincarnation transition.

Some parts of Asia still showcase hanging coffins

CNN reports that in China's southern province of Sichuan, you'll find hundreds of hanging coffins, telltale signs of a people who died out about 400 years ago, the Bo. The Bo lived in the remote valleys south of the Yangtze River, a body of water that runs between China's east coast and the Himalayan foothills.

What do the final remains of the Bo look like? The coffins prove nearly invisible from the ground below. But a closer inspection reveals the coffins sit in cliffside crevices supported by wooden stakes. In some places, the Bo carved rectangular spaces into the rock face to make more room for the caskets, and they stacked others within caves. Archaeologists hypothesize that the placement of the coffins represents an expression of filial piety.

Interestingly, this ritual burial style remains alive and well in the Philippines according to the BBC. There, the Igorot people of Sagada line the cliff faces of Echo Valley with coffins. The tradition dates back more than 2,000 years, and locals secure the hand-carved coffins with nails or ropes. These gravity-defying final resting places are thought to help the deceased become better integrated with their ancestral spirits.

Jazzing up funerals in New Orleans

Although there are more recent developments in New Orleans funerary traditions, many residents still opt for a good old-fashioned jazz funeral, as reported by 64 Parishes.

During these events, mourners follow a marching band that begins by playing traditional dirges. These songs also include spare Christian hymns performed at a slow tempo. But after the body gets laid in the ground, the band makes a drastic transition, according to the New Orleans tourism website. Instead of playing more serious music, the band will "cut loose," breaking into toe-tapping, upbeat dance music after the burial.

How did such a festive tradition get associated with something as sad as a funeral? Instead of focusing on the loss of the deceased, New Orleans jazz funerals emphasize the person's life at the moment of death. Today, jazz funerals remain highly popular in Louisiana, and a growing number of people are opting for them.

Taking funerals to new heights with burial trees

Many Native American tribes utilized trees as final resting places. In some cases, they also built scaffolding to simulate trees, providing high places to leave their deceased. They wrapped dead bodies in blankets or robes and then secured the cadavers in a fork of branches. In some cases, robust trees might support multiple burials.

According to Britannica, the practice of exposing the dead in an elevated tree or scaffolding burial also included. In some instances, as with Sioux tree burials, participants sewed the deceased into a buffalo hide or deerskin. The Naga of India, the Aborigines of central Australia, and the Bali Aga of Bali also placed bodies at least eight feet off the ground and often included grave goods with them. These might consist of personal items such as weapons, pipes, and even the deceased's hair (via AMC).

While practices varied, many tribes left the bodies of the dead in treetops or on scaffolding for one year. At the end of this period, they would remove the decomposed body to transfer it into the ground.

The rise of drive-thru funeral homes

Drive-thrus are all about convenience, and this proves no less true when it comes to funeral homes. According to Connecting Directors, Adams Funeral Home, located in Los Angeles County, understands this better than just about any business. You see, for the past 40 years, Adams has been in the drive-thru funeral business, and it has proven quite lucrative.

Located in Compton, the facility provides the utmost in convenience and safety, whether you're an elderly individual with limited mobility or a gang member looking to honor a comrade without getting into an altercation. The funeral parlor's bulletproof façade provides safety and peace of mind for those who might otherwise feel hesitant to gather for a viewing.

Of course, other current events have also contributed to the popularity of drive thrus, including the COVID-19 pandemic. After all, there's no better place to social distance. How many other drive-thru funeral parlors will you find in the United States? They include locations in Louisiana and Chicago.

Charnel houses only house the dead

There's a Cornish folktale that provides the perfect introduction to our next bizarre burial custom, the charnel house. As the story goes, a man accepted a bet to head into his parish's charnel house to steal a skull. But after entering the macabre establishment and picking up a defleshed head, a spectral voice proclaimed, "That belongs to me." After this happened two more times, the living man defiantly replied, "These skulls can't all belong to you!" Then, he ran off with a head, winning the wager.

As this cheeky tale demonstrates, charnel houses proved common enough in Britain to get immortalized in humorous tales. But what are charnel houses? Also known as corpse houses, or mort houses, they are simple, windowless buildings that look like sheds or pump houses. But their interiors prove decidedly more gruesome, featuring wall niches to hold caskets. Each house is secured with a sturdy lock to keep grave robbers away, like the man in the Cornish story.

According to the New York Times, you can still visit some of these dead houses today, especially in parts of the northern US and Canada, where the ground is often too cold to bury bodies for months out of the year. But these days, they typically hold nothing more than tools. After all, advances in technology, from backhoes to excavators, have ensured easy accessibility to ground burials.

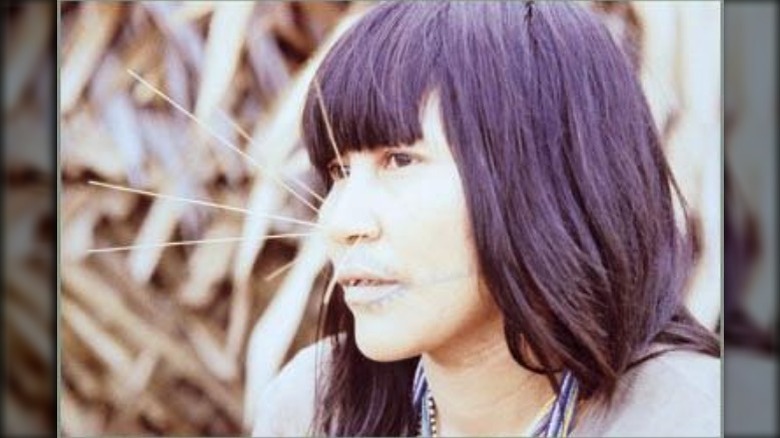

Funerary cannibalism throughout the world

Few funerary practices prove more controversial and dangerous than the custom of endocannibalism. What does endocannibalism entail? It refers to the consumption of human flesh among those within the same social group. Practiced among a variety of people groups, including the Mayoruna (pictured), the Wari', and the Amahuaca of the Amazon Basin, funerary cannibalism has also been practiced by the Jukun of West Africa and some tribes in Papua New Guinea (via Alimentarium).

The tribes that practiced anthropophagy saw it as a way to ensure the deceased would remain with the living. Endocannibalism maintained the continuity between life and death, and some of these tribes thought the act perpetuated the presence of the dead relative.

Considered a taboo among many people groups, endocannibalism came with dangerous health consequences, including the acquisition of the incurable, debilitating, and ultimately fatal disease, kuru. The disease takes between 10 to 13 years to manifest, although some individuals have seen incubation periods of 50 years or more. What researchers know about kuru today comes largely from tribes in Papua New Guinea that once practiced endocannibalism and exocannibalism.