Here's What Happened To The Bodies Of These Popes

Much is made of a pope's life, and rightfully so. The pope is the spiritual leader of Catholics worldwide, not to mention the temporal leader of the Vatican City, where he's technically the absolute monarch of the tiny nation. Pontiffs have also often wielded some pretty serious political power throughout history. Take the medieval Pope Innocent III, who was one of the most powerful Holy Fathers ever. Innocent ordered multiple crusades in the Holy Land and was, on multiple occasions, the person who gave the all-important go-ahead for a nation to crown a new ruler.

Popes, therefore, can have a pretty profound effect on the world while they're alive, and that visibility and veneration of their lives tends to carry on through their deaths. Even the humblest of popes can expect to have a relatively elaborate, highly ritualized funeral. Some, attempting to reform the traditions dictating the treatment of their bodies after death, produced plenty of trouble for their surviving staff. And one living pope in the 9th century was so insecure that he rekindled an old fight, even though his papal predecessor and rival had been dead for some time.

Since the first pope, St. Peter, there have been over 260 popes, and that's before getting into the weeds of antipopes and multiple living popes, the latter having occurred more often throughout history than you may think. Suffice to say, the stories behind the locations of the final resting places of popes are rich, complex, and sometimes just a little torrid.

Most popes go through a complex burial ritual

While popes can dictate some details of their funeral ahead of time, the force of history has proven to be pretty strong when it comes to papal send-offs. Most popes therefore stick with long-held traditions, which can be pretty detailed.

A pope's body will naturally be dressed in the sort of religious garb he would have worn during life. It's then placed inside the first of three coffins, a wooden one that's supposed to represent the fact that the pope is but a simple man. It's eventually placed inside a somewhat fancier zinc coffin with his name and the dates of his reign engraved on the surface, hermetically sealed against the outside world, and then put inside a second wooden coffin, this time made of oak. The whole assembly is placed beneath a marble slab or, in the case of some pontiffs, inside an entire marble sarcophagus.

Those aren't the only rituals closely followed in the wake of a pope's death. The Vatican observes a 9-day mourning period that's linked to ancient Roman customs. It also typically involves a public viewing. The funeral itself must take place between the fourth and sixth day after the pontiff dies, though it's not immediately clear why. After the service in St. Peter's Basilica, the pontifical coffin is carried out through an ominously named "door of death" for the final internment beneath the church.

Some remains of popes may be combed over for relics

After their deaths, popes' bodies may be preserved as wholly as possible for future veneration, which many interpret as the collection of holy relics from the remains of previous pontiffs. Relics, after all, have proven to be a pretty big spiritual business throughout the history of the church. These relics are believed to be a direct physical connection to a saint and can be drawn from any number of body parts, from St. Anthony's tongue to St. Catherine's head to the bones of the first pope, St. Peter.

This may have been why Pope Benedict XVI, the pontiff who famously resigned from his post in 2013, learned that his organ donor card was no longer accepted. Federico Lombardi, the chief spokesman for the Vatican, claimed that it had nothing to do with the possibility that Benedict's future remains would be reserved for relic-collection if he were declared a saint, but that did little to dispel the theory.

It's certainly happened before. On multiple occasions, relics from Pope John Paul II — who was made a saint in 2014 — were stolen. One was a piece of the blood-stained robe he had been wearing during a 1981 assassination attempt. Another was a vial of blood collected towards the end of his life, which was stolen from Spoleto, Italy, in 2020.

No one is totally sure what happened to St. Peter's body

When it comes to popes, St. Peter is kind of a big deal. It's not only that he was an original apostle of Jesus and in fact the head honcho of the 12 apostles. There's also the matter that, according to widespread Christian tradition, Peter was the first-ever pope. Like so many saints in early Christianity, legend maintains that Peter met a gruesome end, crucified upside down by authorities under the ancient Roman Emperor Nero.

All of this means that any relics recovered from the mortal remains of St. Peter would be pretty highly venerated amongst the faithful. Yet, while bones that reportedly belong to Peter have been displayed in the Vatican, the circumstances of these bone fragments' recovery and identification are unclear. The remains were taken from an ancient burial ground under St. Peter's Basilica, uncovered after 1939. It's indeed possible that early Christians would have wanted to be buried near a big-name apostle.

Yet no pope has ever gone so far as to definitively state that these nine bone fragments belong to St. Peter. In 1968, Pope Paul VI did claim that the bones were convincingly identified, but offered precious little evidence beyond that. Skeptics therefore remain, well, skeptical, while believers will have to decide whether or not they want to take it as a matter of faith.

Pope John XXIII went on display long after his death

People really, really loved Pope John XXIII. He was a widely admired pontiff, to the point where he became known simply as the "good pope" for his welcoming nature and relatively liberal attitudes. He was the pope who oversaw the Second Vatican Council, a major development in church administration and theology that sought to bring Catholicism in line with more modern ideals.

Given how much people venerated John XXIII, despite his short reign from 1958 to 1963, it's no wonder that there were soon rumors of his purported sainthood. He was linked to a nun's disappearing stomach tumor, for one. And when his tomb was opened in 2001, his remains were in extraordinarily good condition.

However, the church has remained skeptical about this incorruptibility. John XXIII's remains were not embalmed but had been treated with formalin for public viewing, and the Vatican reminded everyone that John XXIII's remains were also hermetically sealed inside multiple coffins. Nevertheless, the pope's remains were put on display in 2001 in a glass-sided coffin for public viewing. The body was also outfitted with a wax mask made from a casting of the pope's face, made just after his death.

Pope John Paul II wasn't embalmed

It doesn't appear that the Catholic Church has an official policy regarding whether or not a pope's remains should be embalmed. However, we do have some clues, if information about more modern papal funerals is anything to go by. A number of recent popes have been fully embalmed after their deaths, including all of the four popes preceding John Paul II. The full embalming process requires removing nearly all blood and other bodily fluids from the remains, replacing them with a preservative-heavy solution that also contains dye meant to give the body a more lifelike appearance.

In contrast to earlier tradition, John Paul II appears to have not been fully embalmed, whose body was only prepared for a public viewing. It's likely that the pope's body was given some sort of treatment with preservatives to keep it in a presentable (that is, not visibly decomposing) state.

After all, Pope John Paul II died in 2005, well into an era where reporters and news cameras could broadcast any issues spotted during the public viewing, while thousands of people were filing past his remains. While some reported telltale signs of deterioration, it appears that whatever the light treatment that was applied to Pope John Paul II's remains, it worked far better than for other popes who experienced similar preparations.

The body of a pope might be exhumed and moved multiple times

For many, a final resting place should be well and truly final, but that's not always the case for some mortal remains. A famous person might rest pretty uneasily, as fans and researchers alike fail to resist the temptation to dig people up for another look. And, like some other notables, especially within the Catholic Church, a pope may not expect to rest in a single spot forever. If a pope is the subject of a sainthood cause, then their body may in fact be removed from its burial place multiple times over the decades. Vatican officials may want to exhume a pope's remains to put them on public view for veneration or to inspect the remains for signs of sainthood, for instance.

Consider the remains of St. John Paul II. Before he was officially canonized in 2014, his body was taken out of its burial place in the crypt of St. Peter's Basilica and placed back in front of the church's main altar. Thereafter, with beatification achieved, the coffin was put into a new burial spot in a nearby chapel, with the marble topper from his old sarcophagus sent to the pontiff's old home country of Poland.

Pope Pius X stopped an embalming tradition he found extra creepy

Though much is made of the ancient and storied traditions that are part of life in the Vatican, things can and indeed do change. Sometimes, those changes are sweeping, even monumental, like those enacted by the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. Vatican II, as it's often called, loosened rules for some religious order members and allowed for mass to be held in numerous local languages and not just Latin. It was also, of course, fairly controversial and led some conservative members of the church to complain well into the present day.

Then again, sometimes the changes to tradition are seemingly small, though they can have big consequences later. Take Pope Pius X, who died in 1914. He refused to allow embalmers to remove his internal organs and preserve them in separate jars. It was by then a pretty well-established practice that had been enacted in the wake of previous popes' deaths.

But Pius X thought this all was nothing short of grotesque and his successors seemed to agree. Yet, where the remains of Pius X seem to have suffered no great damage from this new tradition, other popes' bodies — with quickly deteriorating organs still intact inside them — would not be quite so fortunate.

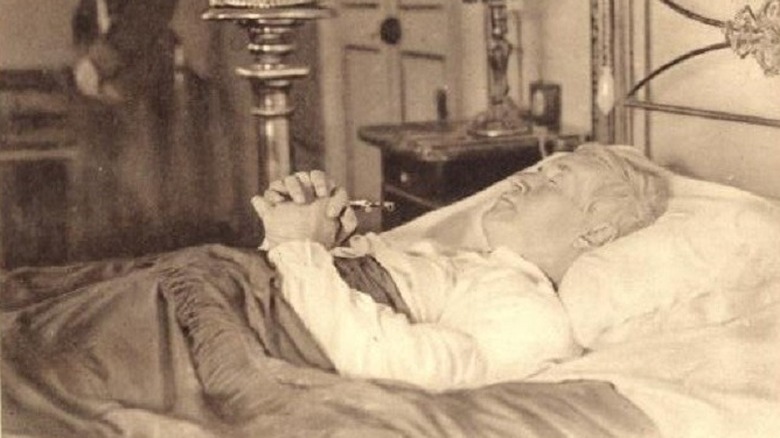

Pius XII went through a disastrous embalming process

No one seems to know exactly why Riccardo Galeazzi-Lisi was put in charge of embalming the pope. The scheming, incompetent personal doctor of Pius XII wasn't exactly a figure who inspired confidence when he appeared in the papal apartments. And it was eventually revealed that he was behind the deathbed photos of the pontiff that had been leaked to the press in 1958.

The embalming was a disaster, not least because Galeazzi-Lisi was a quack who had made promises he simply couldn't keep. Together with another presumably incompetent surgeon, he had developed an "aromatic osmosis" method that had supposedly been used by the ancients. It basically required that someone dress the body in various oils and then wrap it in a sheet of plastic, with no injections or incisions.

The process did absolutely nothing to slow down the decay of the remains, ultimately producing smells so bad that members of the Swiss Guard reportedly fainted while standing guard around the coffin. Even worse, the pope's remains were so bloated with gases produced via decomposition that they popped within his coffin — in the middle of his funeral procession in Rome. Galeazzi-Lisi and associates hastily re-embalmed the remains, but it was still pretty awful. Some even reported that Pius XII's remains had turned a lurid "emerald green" because of Galeazzi-Lisi's lackluster ministrations.

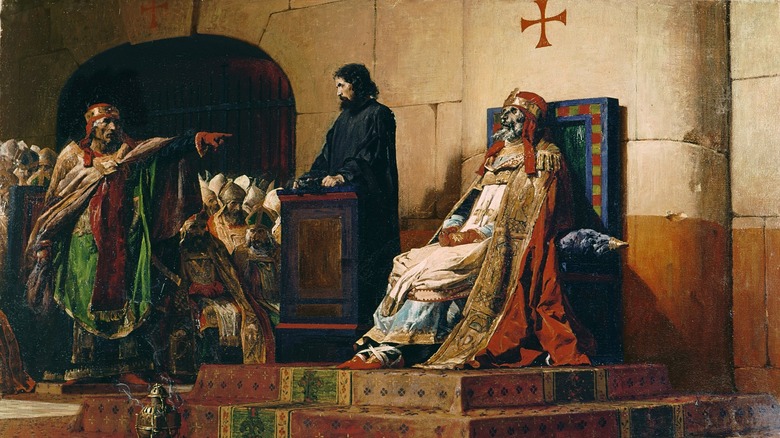

The Cadaver Synod brought a fight between popes to a gruesome head

While there's plenty to shake one's head at when it comes to relic hunting and experimental embalming, those mishaps can't measure up to the infamous Cadaver Synod. It essentially began in 897 CE, when Pope Stephen VI decided that his predecessor, Pope Formosus, had committed a great sin (or had proven to be politically inconvenient to Stephen's way of doing things). Formosus had once been a pretty powerful bishop, and Pope John VIII got so nervous that he had Formosus excommunicated. John was eventually killed and his successor reinstated Formosus, who managed to snag his own spot as pontiff for five years before dying. By this time, the papal throne had a pretty high turnover rate, and anyone sitting there was bound to feel pretty nervous.

So, Stephen VI held a trial for Formosus, whom he believed had broken some key rules when he became pope. Stephen had his predecessor's remains exhumed, dressed in liturgical robes, placed in a chair, and put on trial.

Being dead, Formosus was not really able to defend himself against the charges and was quickly found guilty. His remains were unceremoniously tossed in Rome's Tiber River, where a fisherman pulled the body out of the water. Formosus' remains were soon linked to rumors of miracles. Stephen was unsurprisingly felled by an uprising and the body of Formosus was reinstalled in a tomb beneath St. Peter's Basilica.

Pope Paul VI also had a pretty disastrous funeral

Pope Paul VI's remains were only lightly embalmed after his 1978 death. While that seemed to have worked out decently enough for one of Paul's successors, John Paul II, the reality of the 1978 funeral was quite a bit more gruesome. Part of the issue may have been with not only the manner in which the deceased pontiff's body was treated, but with the environmental conditions in the midst of what seems to have been a hot and humid summer.

The combined effects of the lack of embalming and the summer weather were unfortunate for Paul VI and his mourners, to say the least. Reportedly, a number of fans were installed around the pope's remains as they lay in state inside St. Peter's Basilica. It was done in order to somehow redirect the stench during the public viewing.

Meanwhile, as then-first lady Rosalynn Carter spoke glowingly of the pontiff's spiritual life, some couldn't help but notice that the pope's body had turned an alarming green-gray color. The Vatican declined to say just what had or had not been done to Paul VI's remains in the immediate aftermath of his death, but it was clear that it hadn't been enough to stand up to the rigors of a summertime memorial.

Benedict XVI's was the first to include his successor in over 200 years

It can take a minute to elect a new pope, so most pontiffs are buried without the next pope present. The man who will become the next pope may be present as part of his current office — Benedict XVI delivered a homily during the rites for John Paul II — but he is not there as pope, given that no one (except God, presumably) knows he will be elevated.

A notable exception to this rule of thumb was Benedict XVI himself, predecessor of Pope Francis. Benedict's resignation had surprised pope-watchers, as the practice had no recent precedent, and so when Benedict died in late 2022, his successor had been in office for years. The most recent example of a pope burying his predecessor was a weird one, since it involved returning the remains of a pope who had died in exile during the ructions of the Napoleonic Wars.

Ultimately, Francis presided over a solemn funeral slightly less ornate than the protocol for a pope who had died in office. Dignitaries attended, but most did so in a technically private capacity, with only delegations from Italy and Benedict's native Germany attending formally as representatives of their nations. These were joined by emissaries from a number of Christian churches, as well as an imam giving the respects of Italy's Muslims.

During the Avignon Papacy, several popes were buried in France

Most popes are buried in Rome, given that city's centrality to the church and, more prosaically, the fact that the pope generally lives there. Among the popes buried in Rome, most rest in the grottoes beneath St. Peter's Basilica, though some popes lie elsewhere. But the papal residence has not always been in Rome: for 68 years in the 14th century, popes reigned from lovely Avignon in southern France, where the former bishop of Bordeaux, Clement V, had set up his capital to escape factional infighting in Rome.

Unsurprisingly, the Avignon Papacy was unpopular in a number of countries that weren't France, and when a later pope moved back to Rome, another was elected to fill the "empty" Avignon seat. The resulting schism lasted from 1377 to 1417, during which time there were usually two and eventually three men claiming to be pope, each supported by different European powers.

Five of the six popes elected during the Avignon Papacy are buried in southern France, three in Avignon and two nearby. Clement V himself is buried in the small town of Uzeste, in southwest France, furthest from Rome of all recorded papal burials.

Pius IX had to be secretly transferred out of the Vatican

For centuries, the pope was also the monarch of a chunk of central Italy generally known as the Papal States. As Italian unification progressed during the mid-19th century, the Papal States would become the last and most symbolic prize. If the emerging Kingdom of Italy could gobble up the pope's land, all Italy would again be ruled from Rome — and not by the pope. On September 20, 1870, Italian soldiers poured into Rome, challenged only by a single symbolic volley from the papal forces.

The jockeying over the exact relationship between the church and Italy that would eventually lead to the creation of the modern Vatican City lasted until 1929; the pope who lost Rome, Pius IX, lasted until 1878. Rome was still tense after its absorption, so he was buried within the Vatican instead of his preferred church, St. Lawrence, so the body did not have to be transported through a potentially hostile Rome. Three years later, Pius IX's earthly remains were snuck out under cover of night to be placed in the church he had chosen, only to be met with hoodlums: someone had tipped off an anti-clerical element who were intent on throwing the holy corpse into the river. They were dispersed, and Pius made it to St. Lawrence.

Leo XIII chose a roommate

Innocent III, who reigned from 1198 to 1216, was among the most consequential popes in history, expanding papal authority and prestige both within the Papal States and abroad. Naturally, this exemplar of a pope who distinguished himself as both a spiritual and political leader attracted admirers, especially among his successors. Leo XIII was so enamored of Innocent that he wished to be buried next to him — a wish he pursued by moving the long-dead Innocent.

You see, Innocent had died suddenly in Perugia, some 85 miles from Rome, and had been buried there, given the time-sensitive realities of managing a corpse during the Italian summer. Leo XIII had a pair of tombs installed on either side of the doorway of St. John Lateran in Rome and had Innocent transported there in 1891, saving the other for himself. It took a while, as when Leo XIII died in 1903, people reasonably feared a donnybrook like the one that had accompanied Pius IX's funeral, so Leo was buried in St. Peter's until it seemed safe to move him to his chosen resting place ... 21 years later.

More than half are (or at least were) buried in St. Peter's Basilica

Though popes may choose their resting places (or have circumstances choose for them, in the case of deaths abroad that preceded modern mortuary science), most have been laid to rest in St. Peter's Basilica. The current Renaissance building is indeed one of the wonders of the modern world and showcases the glory and history of the Roman church, with treasures including frescoes by Michelangelo and an ancient wooden throne said by the more optimistic of the faithful to have been the seat of St. Peter, the first pope.

In addition to the obviously attractive beauty and pageantry of the basilica, a pope resting here would lie among his brethren, the comparative handful of people who have run this ancient religious establishment. Even St. Peter himself, an apostle who received his ministry directly from Jesus, is traditionally said to be buried within the church. Even given the less-than-stellar postmortem reputations of some popes, you could do far worse for eternal neighbors.

A relic of Pope Clement I was found in the trash in England

Catholic tradition establishes pope and St. Clement I to be the fourth pope; his reign at the end of the first century credibly makes him a younger contemporary of the apostles. According to a less likely tradition, he was martyred by being tied to an anchor and thrown into the sea, and so Clement often appears with an anchor in artistic depictions.

Clement's martyrdom is said to have taken place off the coast of the Crimea, then on the edge of the Roman world. For this reason, most of his relics were initially in Ukraine, with some later transported to Italy. And then, of course, some of them were in the garbage in England. In 2018 a London waste collection firm sorting potential recyclables found a little red display case holding a small bone labeled as having belonged to the sainted Clement; it was not clear which site they visited that day had produced the holy bone.

Later investigation proved that the bone was, if not provably Clement's, provably a relic of old provenance. It had been stolen from a car before its unlikely recovery (presumably the previous owner was a nervous driver), and this unnamed relic-chauffer then donated the bone to the Catholic Church.

Antipope Benedict XIII had a messy afterlife in Spain

Occasionally, there was no agreement over who was pope, with two or more men claiming the office; once the matter is cleared up, the losing contestants are termed "antipopes." This can make numbering popes difficult, especially if the determination of who is pope takes place after the fact; the total number of Benedicts and the order in which they occurred is confusing for this reason.

Antipope Benedict XIII, not actual-Pope Benedict XIII, had a farcically messy afterlife. In 2000, a poorly-maintained palace in Aragon in Spain was burgled, with the thieves getting away with the skull of this ecclesiastical wannabe. A ransom demand of 1,000,000 pesetas (Spain's pre-euro currency, for a total of about 15,000 dollars in today's money) went uncollected.

News reports in English on the skull's adventures are slim until 2023, by which point the skull had been recovered only to find itself involved in a custody dispute between the village from which it was stolen and the birthplace of Benedict XIII. The skull was last reported as being in safekeeping in Zaragoza, presumably behind locked doors.

Antipope John XXIII has a magnificent tomb in Florence with a catty epitaph

Antipope John XXIII (not pope-pope John XXIII) was elected in the early 1400s as the Western Schism reached fever pitch: recklessly, a third pope had been chosen to try to override the claims of the two active claimants, which predictably led to there being three "popes" running around, one each for Rome, Avignon, and Pisa. John XXIII succeeded the Pisan antipope Alexander V, but was ultimately dethroned and imprisoned after a church council met to resolve the multipope issue once and for all.

John XXIII was sprung from captivity thanks to money from his backers the Medicis, the fabulously rich leading family of Florence. In a no-hard-feelings gesture, the now-singular Pope Martin V made John XXIII, now plain old Baldassare Cossa again, bishop of Tusculum.

When Cossa died a few months later, his allies the Medicis were ready to make a statement. They entombed Cossa in a beautifully ornate tomb of marble and gilded bronze that reflected all the magnificence of the emerging Renaissance. Famed sculptor Donatello worked on the monument, though his exact contributions are undetermined. And in an apparent dig at Martin V, not only does the design include the papal coat of arms, but the epitaph begins "John, former pope..."

Celestine V's remains survived a terrible earthquake

Pope and St. Celestine V was the first pope recorded to have abdicated, occupying the papal throne for a mere five months before vacating the office in hopes of returning to a private life of prayer. Given the weirdness of his abdication, he was imprisoned instead. Assessments of Celestine have been mixed: the Church made him a saint, but Dante, one of many people who hated his successor Boniface VIII, put Celestine in hell in his "Inferno".

Celestine's remains lie in L'Aquila, in central Italy, the capital of Abruzzi and a beautiful medieval city that still retains much of its medieval walls. These treasures were badly damaged when a strong earthquake struck the city in 2009, toppling monuments and killing over 275 people. One notable "survivor" was Celestine, whose grave escaped damage even though the church containing his grave needed significant repair. The head of Italy's Heritage Security Commission called it a miracle through Celestine's intervention; cynics might have preferred Celestine extend his protection to someone better able to enjoy it.

Future papal funerals will be simpler

Papal funerals were updated to be simpler under a newly codified ritual approved by Pope Francis, who died on April 21, 2025. After the death of his retired predecessor Benedict XVI on the last day of 2022, protocol had to be worked out for the funeral of a former pope (as opposed to one who had died in office). This situation had not arisen since the early 1400s, which emphasized both the unusual nature of Benedict's decision to abdicate and how far back planners had to look for precedent.

Francis's reforms promote relative simplicity — after all, a papal funeral can only be so simple — and an emphasis on the pope as fundamentally a bishop: the pope is, technically and primarily, the bishop of Rome. Notably, the papal remains will be enclosed in a simple wooden coffin instead of the traditional three; the requirement of lying-in-state on an elevated bier is also to be nixed. That said, NBC News reported that Francis's body would spend three days at St. Peter's Basilica lying in state. Pope funerals are always at the Vatican, ideally in St. Peter's Square.

Additionally, Francis's preference for his own resting place has been confirmed. He will be buried in Santa Maria Maggiore, another Roman basilica, instead of St. Peter's, which houses the remains of most of his predecessors, apparently due to the presence there of an icon of Mary with special significance for the pope.