The Truth About Turkmenistan's 'Gates Of Hell'

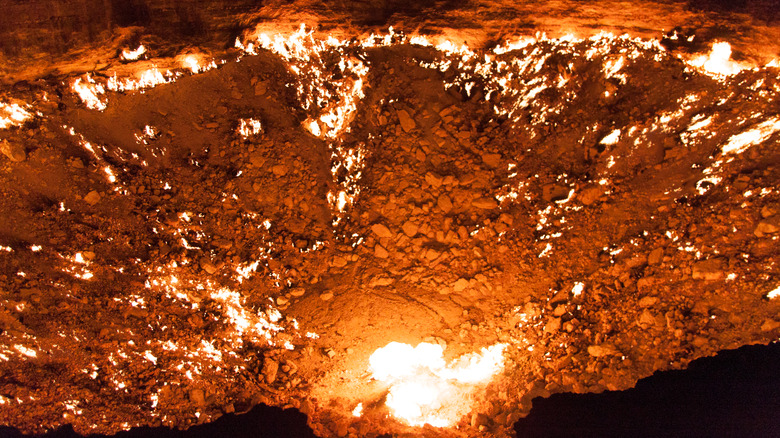

Let's be honest: if a geographic formation on Earth is dubbed the "Gates of Hell," you've got a pretty particular, and pretty high, set of expectations. Are we talking about a vast crater hole-punched into the flat expanse of a desert, its sudden-edged drop-off falling into charred, rocky guts licked by endlessly roiling flames, smoldering in the day and the night like the eye of Sauron branded onto the face of the earth? Why, yes, actually. That's exactly what it is. Think we're exaggerating? Have a gander over on Atlas Obscura. The only thing the crater is missing is a couple of prong-tailed devil guardians pulled from Milton or Dante.

The "Gates of Hell," sometimes called "Gate to Hell," "Door to Hell" — you get the idea — is a one-of-a-kind landmark pockmarking the face of Mother Earth. The 230-foot-wide pit has burned ceaselessly for the past 40 years in the middle of the Karakum Desert near the 350-person village of Derweze (also written Darvaza), Turkmenistan. Day and night it spews noxious fumes and lights up the desert floor like a second sun. Once a national embarrassment, now a tourist hotspot (literally), folks can visit while caravanning for weeks on personalized tours from Uzbekistan to Iran to Kyrgyzstan and back again, such as that described on Caravanistan, barbecuing in the frosty desert nights and waving at roadside camels along the way.

So what in the, erm... hell is going on with the Derweze Crater? Is it natural? Artificial? Satan-made?

An accidental creation of Soviet geologists in 1971

The Derweze Crater is, above all else, an accident. As Turkmen geologist Anatoly Bushmakin says on CTV News, in 1971 Soviet geologists started drilling for natural gas (Turkmenistan has the sixth-largest reserves of natural gas in the world, per The Guardian) and punctured an underground cavern. Their equipment fell through, the hole collapsed in on itself, and poisonous methane fumes started escaping into the air. Officials tried to rectify the situation by igniting the gas, believing it would burn off after a couple of weeks. But no, the methane just continues to fuel those same flames to this very day. People such as Canadian explorer George Kourounis describe the absolute, scorching heat given off near the crater's edge.

The Turkmen government straight up ignored the flaming pit for a long time. In fact, it's only recently — sometime before February 2021, judging by this Caravanistan article — that a fence has been erected, and this only at the prospect of tourist money. A small, cottage industry of tourism has sprung up around the site, utterly unmarked in the middle of the Karakum ("Black Sands") Desert, one of the largest deserts in the world, about 270 kilometers (168 miles) north of Turkmenistan's capital, Ashgabat. Now, there's talk of safaris, extreme desert sports, and an ecotourism boom to enkindle Turkmenistan's meager 12,000-15,000 annual foreign visitors. In fact, in 2020, Turkmen President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov established a 220,000-acre nature reserve in the Karakum Desert that covers the Derweze Crater.

A site of awe and contrition for explorers and tourists

In 2013, aforementioned Candian explorer George Kourounis went on an expedition to be the first person to descend from the 97-degree Celsius (207-degree Fahrenheit) lip down into the flaming, gravely belly of the Gates of Hell. It took a year and a half of planning, per National Geographic (whose Expeditions Council helped with funding), getting permission, hammering out logistics, assembling a team, hiring a Hollywood stunt coordinator to teach him how to deal with fire, obtaining a heat-resistant, silvery, retro spaceman-looking suit with a breathing apparatus, and manufacturing a custom-made Kevlar harness for the rappelling descent because other materials would have melted. As he said in The Guardian, once inside, he stood in a "coliseum of fire" filled with thousands of small flames as loud as a "jet engine." His goal, he said, was to determine if similar locations out in space could support life.

For the rest of us, there are loads of travel advice on Caravanistan. On CTV News, tour guide and Ashgabat resident Begli Atayev describes travelers' awe at the crater mixed with disbelief about how it remained untended for so long. Even though the majority of visitors to the "Gates of Hell" are foreign, Turkmen have gone on pilgrimages, too. Gozel Yazkulieva describes an experience akin to the religious allusion contained within the site's name, saying, "You immediately think of your sins and feel like praying."

Perhaps the crater was well-named, after all.