The Unusual Truth Of The Veiled Prophet Ball

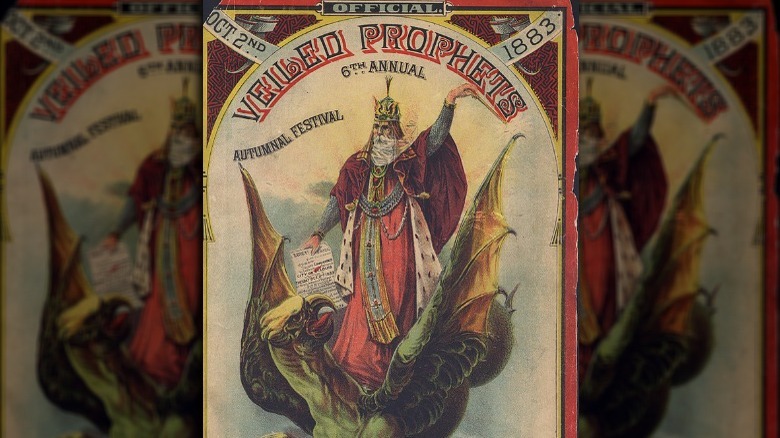

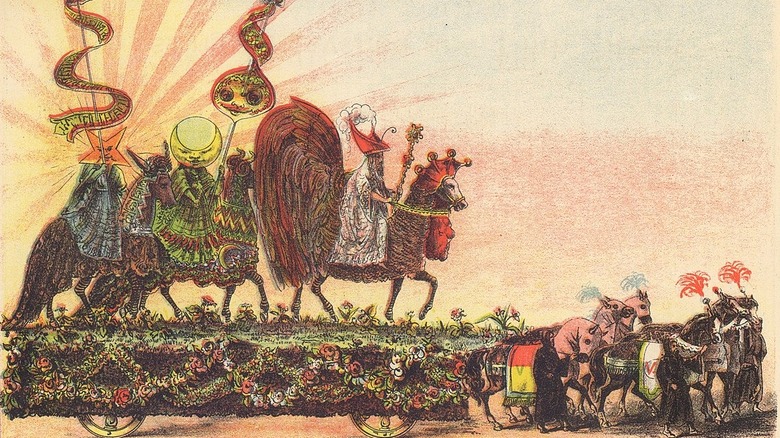

"You are hereby commanded to appear at the Grand Ball given in honor of the Veiled Prophet and his Court of Love and Beauty at the Chamber of Commerce St. Louis, Tuesday October 3rd, 1899," the invitation reads, viewable on the Duke University library. It's double-sided, coated in hand-drawn illustrations of flowers, multi-headed dragons, cherubs, Little Red Riding Hood, and a veiled, sleeping king, all looking lifted directly from the cover of a 1970s Anne McCaffrey novel. Yes, it's legit, yes, it's all vaguely creepy, and yes, it all plays out like Bohemian Grove meets off-brand Disney cosplay in a bizarre, oddly pagan fantasy pageant for the wealthy. And hang on, Pop Culture says that Ellie Kemper from "The Office" was named "Queen of the Veiled Prophet Ball" in 1999 when she was 19??

Let's dial it back a bit. First, have a look at some of the pictures on Twitter from this, uh ... ball? Father-and-daughter prom? Cinderella's Castle featurette? Even without the covered faces of priestly vestment-wearing dudes wielding holy staves, it's enough to make you clutch your children and give them firm reminders never to take candy from strangers.

According to the Veiled Prophet Organization website, the whole thing is "the preeminent formal gala for introducing young ladies, generally in their sophomore year of college, to the St. Louis metropolitan community," and includes a "pageant, reception, Queen's Supper and early morning breakfast." Or as Jezebel's headline says, "What the H*** Is This Racist Debutante Parade in St. Louis?"

A secret society of St. Louis elites formed in the aftermath of the Civil War

Time to get to the cosplaying core of things in the post-Civil War United States, 1878. Per The Atlantic, the "VP Fair" ("Veiled Prophet") was formed by a former Confederate cavalryman with the very actual name Charles Slayback. At this point, remember that Missouri was a "seedbed" of the Civil War, and over its duration, was internally embroiled in a conflict over its identity, statehood, and position on slavery, as Essential Civil War Curriculum recounts.

After the war, Slayback turned to business. As the tale goes, he called a meeting of local business owners and politicians to form a "secret society." What would this secret society entail? It would "blend the pomp and ritual of a New Orleans Mardi Gras with the symbolism used by the Irish poet Thomas Moore" (Moore was, as Britannica tells us, a contemporary and friend of revered poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron).

To this end, Slayback invented what might have been intended as a vaguely folklore-ish tale of the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan, who embedded himself in St. Louis' upper crust. An anonymous, local elite would don his role in an annual ball, elect a young girl as his consort, dance the "Royal Quadrille" with her, give some expensive gifts to her family, and fast-forward to 1992: the name of this whole parade-slash-pageant-slash-creepo gala was changed to the familiar "St. Louis Fair."

The ball's KKK look didn't hold up too well

Before you say, "Why didn't Slayback just write a book to indulge his weird fantasies?" it's important to point out that this ostensibly kooky bonanza played a very real role in not only the class relations of St. Louis but race relations.

The first parade in 1878 attracted 50,000 spectators. It's likely, per The Atlantic, that Slayback wanted to "take back the public stage from populist demands for social and economic justice" by portraying an "empty shell that contained the accumulated privilege and power of the status quo." This all happened as the industry of St. Louis was failing and workers staged a strike that turned violent when 5,000 federal troops were sent to the city. Eighteen strikers were killed. These strikers were journalistically characterized as "tramps and loafers" who were "anxious to pillage and plunder" (sound familiar?).

And those who played the Veiled Prophet? They wore KKK-looking hoods. Pop Culture points out that the KKK didn't start wearing such hoods until 1915, but given the fair's whole "let's celebrate the repression of the underclass" heritage, plus Missouri's status as a slave state, pointed hoods aren't a good look. More to the point, per Just Jared, Black people weren't allowed to participate until 1979.

So: Ellie Kemper. In 1999, she wore to the event a "white satin square-neck gown designed by Tomasina and purchased at Saks Fifth Avenue." Unwitting teenage participate though she was, her social media hasn't reacted well.