Natural Phenomena We Still Can't Explain

The world's a weird place, even if you don't believe in things like Bigfoot and ancient aliens. We've come a long way, thanks to a lot of brilliant minds and a ton of science stuff, but it turns out that there are some things we just can't explain. Some natural phenomena are so weird that everyone's just still shaking their heads, even here in the 21st century.

Skyquakes

You're sitting at home, getting your Netflix on, when you hear what sounds like a cannon being fired in your backyard. You go outside to see what the deal is, and there's definitely no Civil War reenactment going on. There's nothing you can see going on, in fact ... but the sounds continue. End of the world? Have the Four Horsemen upgraded from cavalry to an armored tank division? No one's sure.

They're called skyquakes, and they've been happening all over the world for a long time. Washington Irving even wrote about them, saying the sounds came from a ghostly game of bowling. As awesome as that sounds, it's unlikely. We have scientific explanations for it. The problem is we have so many scientific explanations that no one's sure which one's right.

Proposed explanations include tsunamis, methane eruptions, a meteor falling and exploding, and (in some particular areas) the shifting of sand dunes. It's also possible that skyquakes are caused by earthquakes, which is cool. Even cooler, though, is The Daily Mail's suggestion that they're signs of a giant government conspiracy involving super-secret, super-advanced spy planes. No one should believe that, because they're The Daily Mail ... but then again, maybe that's the perfect cover.

Ball Lightning

When US Naval Research Laboratory physicist Graham K. Hubler was 16, he was riding his bike through a thunderstorm (as 16-year-old boys do) when he saw a sphere of lightning the size of a tennis ball floating through a park until it came to a pavilion. It hissed and flew back up into the air, almost as though it was following something. No one believed him, and it was another 10 years before he found out he wasn't crazy.

Ball lightning is so rare that there's little footage of it, even though there are thousands of unconnected accounts of it from all over the world. Most instances only last about 10 seconds, and it's thought that ball lightning has killed at least one person — electricity researcher Georg Richmann. But with so little documentation, others refuse to believe in lightning that stubbornly refuses to obey some pretty basic laws of physics.

The Oh-My-God Particle

In 1991, scientists discovered a particle over the Utah skies. Why was this important? This is going to get a bit sciency, so buckle up.

Drop a bowling ball on your toe. (Not really. Just imagine it.) The bowling ball hurts, right? All that energy is spread through all the atoms in the bowling ball, and if you remember anything from science class, that's a huge number of atoms. The energy in the Oh-My-God particle is the equivalent to the energy in that bowling ball, but it's contained in a single particle. That's more energy than we've managed to give any particle, even with the Large Hadron Collider. The Oh-My-God particle also moves so fast that it broke what we all thought was the cosmic speed limit.

In theory, we should be able to see what's causing such a high-energy particle. But for now, scientists can only scratch their heads and build bigger and bigger ray detectors in an attempt to figure out what the heck threw that cosmic spitball at us.

The morning glory cloud

We know what kinds of weather patterns cause most clouds, but the morning glory cloud is something entirely different. Morning glory clouds are shifting, crawling, rolling tubes that stretch for hundreds of miles. One of the places they form with at least some kind of regularity is over Australia's Gulf of Carpenteria, and hard-core hang gliders head to Queensland to try to surf along the cloud's edge.

The cloud roll moves along at around 25 miles per hour, and they average about a mile high and 300 feet wide. Sometimes, there's one, but other times, a whole series of cloud rolls form. Daredevils who've surfed the edge of the cloud say it's so tightly formed that dipping a wing of the hang glider into it is like running your fingers through a stream of water and breaking it up. Which seriously should make you want to go learn how use a hang glider, right now.

The hum

Maybe you've previously read of the Taos hum. It's named for the town it's heard in — Taos, New Mexico— and it's been driving people nuts since the early 1990s. Just a fraction of the population hear the hum: about 2 percent.

But other hums pop up across the globe, and the 2 percent figure is pretty across-the-board. In 2011, the town of Woodland in England reported the presence of their hum, and they joined a list of towns that includes the English town of Bristol, the Scottish Largs, the Australian beachfront town of Bondi, and, of course, Taos. Most people who hear the hum (who are rather unimaginatively called "hearers") are between the ages of 50 and 70, and the noise has been linked to headaches, nosebleeds, and insomnia. At least one person was even reportedly driven to suicide because of the never-ending, maddening noise, which is something like the low throbbing of a diesel engine running constantly in the background of your mind.

One hum, heard in Kokomo, Indiana, was explained away as coming from a compressor and fan on a nearby industrial site. The others remain unexplained, though, and theories range from farm machinery to UFOs. The smart money, of course, is on the UFOs.

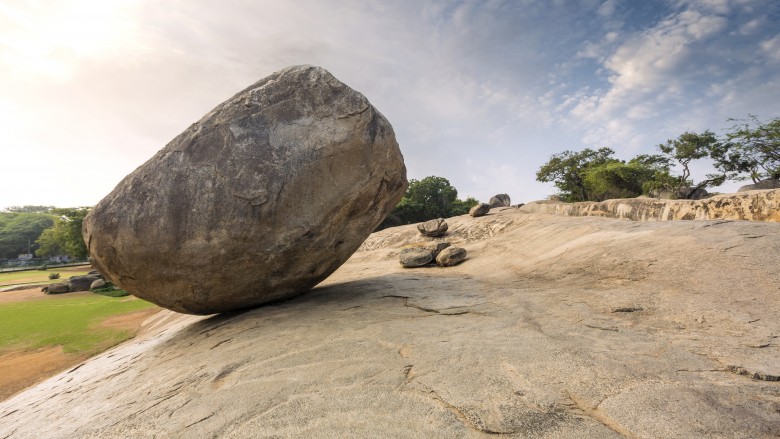

Krishna's butter ball and other balancing rocks

'Krishna's butter ball" is an adorable name for a cat. It's not a cat, though (not yet). It's a 250-ton freak of nature. The massive, 20-foot-high rock sits on a slippery, 45-degree slope in the Indian town of Mahabalipuram. It's famous for somehow not rolling down the hill and smooshing the tourists who insist on hanging out in its shadow (and also for being one of the few surfaces not covered in the carvings that made the town famous).

The rock sits on a base only about 2 square feet wide, and it's believed to have been there for somewhere around 1,200 years. It's also known as the Sky God's Stone because the best explanation for why it's managed to stay there for centuries is that it was touched by the gods.

Not only has it failed to roll down the hill of its own accord — it's thwarted all attempts to push it over, too. Because people are people, and when they see something like this, they need to ruin things, there've been several serious attempts to push the rock down the hill. None have worked, even the one that involved recruiting the pulling power of elephants.

Krishna's butter ball isn't the only weird rock of the sort, either. The rocks in question are known as Precariously Balanced Rocks, or PBRs. Another set sits right alongside the San Andreas fault and stays balanced in spite of the obvious problem of earthquakes. We have all kinds of suggestions for things to try with this particular weird phenomenon, and they all start with the other kind of PBR.

Mass whale strandings

This one's pretty heartbreaking, so apologies in advance.

Mass whale strandings happen on coastlines around the world, and no one knows why. The largest we know about was in Argentina in 1946, when 835 false killer whales stranded themselves near Mar del Plata. The list of mass strandings is hugely long and incredibly depressing, so there's no way we're going to detail them all for you. Britain's Natural History Museum has been keeping track of them since 1913, and they've found some places where it happens more often: Cape Cod, the coast of New Zealand, and the west coast of Scotland. Those are the hotspots, but it happens all over.

One theory says that whales are using electromagnetic signals to navigate and are getting confused. Another says it's a sign that an earthquake's coming, but if they're trying to warn us, they should probably find another way to send a message. Yet another theory says human noise is confusing them and their ability to navigate — specifically, military's sonar interferes with the whales. However, we're pretty sure the military didn't have sonar 9 million years ago, which is how far back some strandings go, according to archaeological evidence.

Whichever theory you choose to believe, feel free not to look at any more of the pictures. They'll just make you sad.

Rogue waves

For almost as long as we've been sailing, we've been telling stories about the incredible and unlikely things that happen to ships at sea. Now, we have buoys that detect the size of waves (and oil rigs at the mercy of the ocean), and there's some pretty terrifying stuff going on out there. While we're still hoping to find out there's something to those places on maps labeled "Here be Dragons," we've recently realized that all those stories about massive, ship-killing waves that came out of nowhere weren't just stories after all.

According to the National Ocean Service, a rogue wave is an unpredictable wave more than twice the size of others in the area. It's thought that they're caused by regular, boring old little waves that somehow sync up and form massive ones, but just how that all works, we're not sure. We do know that they appear out of nowhere, and the biggest ones are walls of water that reach heights of around 100 feet. We've also found that it happens more often than we once thought, probably because most people who previously saw them quickly next saw Davy Jones's locker.

As late as the 1990s, the mere existence of these waves was still up for debate. Now, we know they're out there, but we haven't gotten much further at figuring out what causes them and when they're going to happen. It's both cool and terrifying, because seriously, we didn't need yet another reason to be afraid of what's going on in the ocean.

Ringing rocks

Fortunately, not all of our naturally occurring mysteries involve sadness and potential death. Some are just weirdly cool, while still possibly being the work of aliens.

Scattered across a few locations in Pennsylvania are groups of rocks that ring like bells when hammered. Because it's rural Pennsylvania, and, let's face it, there's not a lot going on out there, there's even records of concerts held there as early as 1890 (likely the first ever rock concert).

Not until 1965 did scientists try to find out what was causing the phenomenon. They broke a bunch of rocks apart to see what was inside. Inside, they found ... rock. Aside from that, they did find that all the area rocks rang. Some just used too low a frequency for us to hear.

Researchers have recorded the phenomenon in a few other places across the world, including a rock field in Whitehall, Montana. History suggests that we've known about this for a long time, too, based on stories about ancient peoples playing rocks as musical instruments.

It gets weirder. Take one of the ringing rocks away from the other rocks (although, we know you'd never try to do that, because you're not that kind of person), and it stops ringing. Maybe it's sad you kidnapped it.

Milky seas

In 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Jules Verne talked about the SS Nautilus coming across a massive patch of glowing ocean. Fiction, right? Not so fast.

In 2005, a satellite image seemed to show precisely that. It's in the Indian Ocean, and it's a patch of bioluminescence the size of Connecticut. It's likely that Verne didn't pull the idea out of thin air, and he based his encounters on sightings from actual ships. That means the patch of glowing ocean spotted by satellites isn't the only one out there.

Researchers are pretty sure microorganisms cause the phenomenon, but just what they're doing, along with how and why they're congregating like that, we have no idea. We just hope they're not planning a world takeover.