The Crazy True Story Of The Family Behind The Opioid Crisis

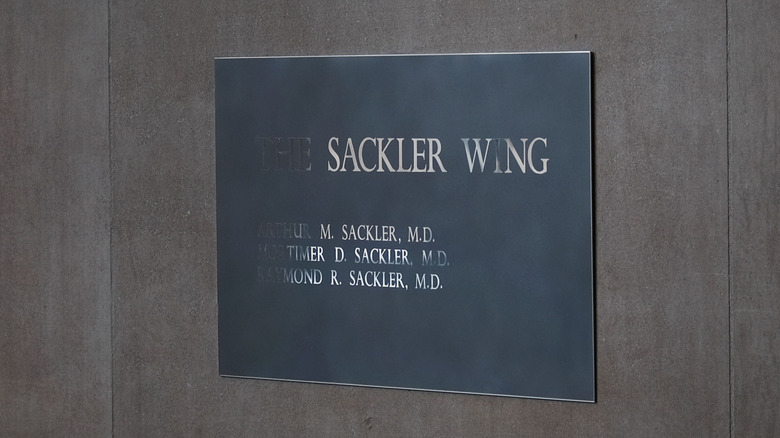

Between 1999 and 2019, it's estimated that at least half a million people died as a result of the opioid crisis. During this time, the Sackler family made billions of dollars peddling OxyContin while deliberately lying about the addictiveness of opioids. For many, the philanthropy of the Sacklers has brought up the question of ethics and whether or not museums or other institutions that depend on donations should turn down gifts from those with "problematic reputations."

As of May 2021, the Sackler family is still working on a settlement regarding their 2020 guilty plea for felony fraud. But despite the billions that they'll eventually have to pay, they'll still remain multibillionaires, especially since the proposed settlement would make their fortune "personally protected from legal action."

But while everyone knows about Purdue Pharma, who makes up the family pulling all of the strings? And although not all of the Sacklers were directly involved with OxyContin, much of OxyContin's success can be attributed to the work done before the drug was even being developed. This is the crazy true story of the family behind the opioid crisis.

History of the Sackler Family

Although the scandals of the Sackler family began during the 1990s, the first Sackler actually immigrated to the United States during the beginning of the 20th century. Isaac Sackler and his wife Sophie Greenberg were Jewish immigrants from what is now Ukraine and Poland who moved to New York and settled in Brooklyn, where they opened a grocery store.

They had three sons: Arthur Mitchell, Mortimer David, and Raymond Raphael. But although the Sacklers were able to provide for their family, during the Great Depression, Isaac informed his sons that he would be unable to pay for any of them to go to college. Isaac Sackler told them that instead, "What I have given you is the most important thing a father can give. A good name," writes Patrick Radden Keefe in "Empire of Pain."

Despite the family's financial difficulties, all three sons ended up becoming psychiatrists. They all worked as pharmaceutical researchers, but according to PBS, Arthur especially made a name for himself "treating mental illness in the 1940s." He was also known for advocating for alternatives to electro-shock therapy. Arthur Sackler worked primarily as the head of a pharmaceutical-advertising company, and later started a biweekly periodical for physicians. Significantly, Arthur ended up making most of his own fortune through marketing Valium in the 1960s, "turning it into the first-ever $100 million drug," according to WBUR.

The three brothers buy Purdue

The three brothers purchased Purdue Frederick in 1952. At that point, it was just a small pharmaceutical company that mainly made laxatives and earwax remover, based in Greenwich Village. And according to The New Yorker, although each brother was going to control a third of the company, Arthur Sackler, "who was occupied with his publishing and advertising ventures, would play a passive role."

But even by playing a passive role, Maclean's writes that Arthur "successfully pioneer[ed] the marketing style and chumminess with government regulators that would serve OxyContin so well." Arthur's advertising bordered on the "blatantly deceptive." In an advertisement for a Pfizer antibiotic, he included business cards with the names of doctors who recommended the use of the drug, even though none of the doctors actually existed. The promotions of Valium and Librium, both tranquilizers from the Roche pharmaceutical company, made Arthur's branch of the family very wealthy, but not as wealthy as the other branches were about to become.

In May 1987, Arthur died of a heart attack at the age of 73. By that point, Purdue Frederick had already moved to Connecticut, and Mortimer and Raymond Sackler soon bought out Arthur's shares of the company for $22.4 million. Around this time, the name of the company was also changed to Purdue Pharma.

The creation of OxyContin

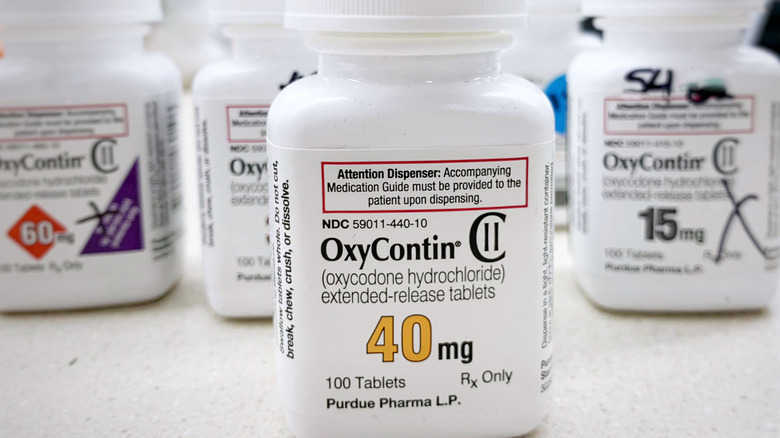

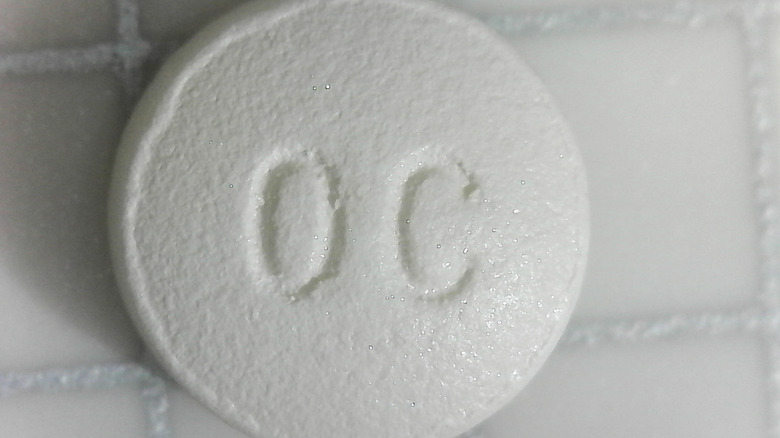

Oxycodone had been around in the United States since the late 1930s, and although it was used as a component as a part of slow-acting medication for pain management, people were voicing concerns about it as early as the 1960s. OxyContin was created as a "controlled-release oxycodone-only formulation," and even though people were having adverse events related to OxyContin in clinical trials as early as 1993, three years later it was approved by the FDA.

Stat News reports that on September 3, 1996, Richard Sackler sent an email to Purdue executives outlining the aggressive marketing approach he wanted to take. Richard claimed that he "want[ed] to get an audience for our patent infringement suits so that we are feared as a tiger with claws, teeth, and balls, and build some excitement with prescribers that OxyContin Tablets is the way to go." According to the American Journal of Public Health, Purdue promoted OxyContin "aggressively" and repeatedly asserted that it was less addictive. From 1996 to 2001, Purdue held over "40 [all-expenses paid] national pain-management and speaker-training conferences at resorts in Florida, Arizona, and California" that were attended by over 5,000 industry professionals.

The precursor to OxyContin was Purdue's MS Contin, which was prescribed to cancer patients for chronic pain. However, "Purdue spent approximately six to 12 times more on promoting [OxyContin] than the company had spent on promoting MS Contin." In his 1994 emails, Richard Sackler refers to their MS Contin business as "a franchise."

Charging Purdue but not the Sacklers

Sales representatives were trained by Purdue to claim that the risk of addiction was "less than one percent," despite the fact that the prevalence of addiction can actually vary from 0% to 50%. As a result, an affiliate of Purdue Pharma, Purdue Frederick Company Inc., pled guilty to federal felony charges relating to the misrepresentation of OxyContin. Three company executives were also part of the plea deal, which also came with a fine of $634 million.

However, it's unlikely that there was no knowledge of the misrepresentation occurring. When OxyContin was first put out in 1996, its label stated that the risk of addiction was "very rare." In 2001, the labeling was changed to claim that "data was not available for establishing the true incidence of addiction," even though there was plenty of scientific literature to suggest otherwise. And Purdue knew it, as they admitted in the lawsuit, writes Nature. As late as 2004, Purdue was submitting promotional material to the FDA that made "numerous misleading or unsubstantiated marketing claims."

However, as The Guardian notes, none of the Sackler family was charged in the lawsuit.

What happened to Raymond Sackler?

All of the Sackler brothers "donated lavishly during their lifetimes," and Raymond was no exception. According to Politico, the Sacklers donated to numerous institutions, especially those working on medical research. During his life, Raymond even ended up being knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in addition to having a minor planet named after him.

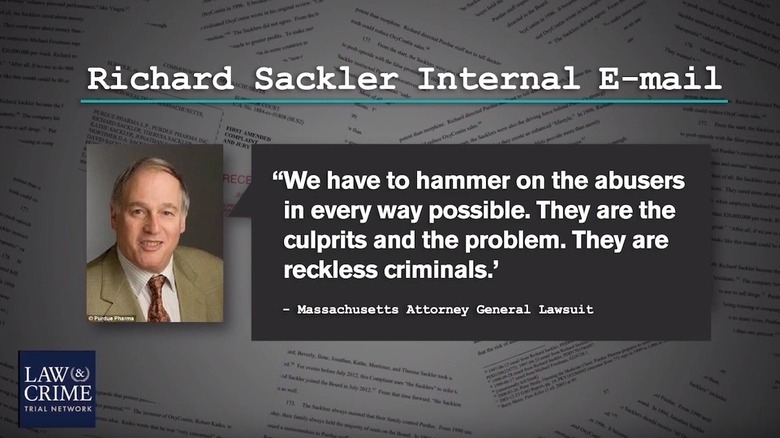

The Guardian reports that Raymond died at the age of 97 in 2017, but his branch of the family ended up being "the most active in Purdue." His son Richard would serve as president of Purdue Pharma from 1999 to 2003, and Maclean's even describes Richard as "Purdue's driving force." Raymond's branch of the family also maintained the philanthropy of the Sackler family. A foundation named after Richard and his ex-wife Beth made donations in 2016 to rightwing thinktanks, "including $50,000 to the neo-conservative, fervently pro-Israel Foundation for Defense of Democracies." Raymond's son Jonathan also advocates for "conservative education reform."

According to The New York Times, Richard played a part in redirecting attention away from OxyContin's addictive qualities and instead blaming those who got addicted as "abusers." In a 2001 email, Richard wrote "We have to hammer on abusers in every way possible [...] They are the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals."

What happened to Mortimer Sackler?

Mortimer Sackler also received an honorary knighthood in his life and lived in London with his family until passing away in 2010 at the age of 93. According to The Guardian, Mortimer's wife, Theresa, as well as his daughters Ilene and Kathe were all board members of Purdue, along with five other Sackler family members. However, by 2019, all the Sackler family members on Purdue's board had left.

Esquire reports that while Raymond ran Purdue, Mortimer was primarily in charge of Napp Pharmaceuticals, the drug company that the Sacklers owned in the United Kingdom. However, in practice, "the brothers worked closely together leading both companies," according to a family spokesperson.

Mortimer's philanthropy was mainly focused on museums, but sometimes even with all the money in the world he couldn't get what he wanted. Apparently for his 70th birthday, Mortimer was angered that the Metropolitan Museum of Art had "agreed to make the Temple of Dendur (pictured) available to him for a party but refused to allow him to redecorate the ancient shrine."

The legacy of Arthur Sackler

Compared to Raymond and Mortimer Sackler's branches of the family, which are now billionaires, Arthur Sackler's side of the family are only "mere multi-millionaires" since they weren't involved in the distribution of OxyContin. Some believe that conflating Arthur with the actions of the rest of the Sackler family is "indiscriminate shaming," since Arthur died before the creation of OxyContin.

It's notable that Arthur's heavy-handed marketing techniques were well-documented by the time the brothers purchased Purdue. And according to Esquire, since Arthur's compensation for the Valium campaign "depended on the volume of pills sold," it's no wonder that Valium became "America's most widely prescribed medication."

Arthur's family was also involved in museum donations, and his third wife, Jillian, was "made a Dame by the Queen for philanthropy." Their daughter Elizabeth (pictured) is also involved in philanthropy, and is a benefactor of a gallery at the Brooklyn Museum. However, as noted to Hyperallergic, none of Arthur Sackler's descendants "have had any involvement with, nor ownership of, Purdue Pharma or benefitted from the sale of Oxycontin in any way." For this reason, institutions that have received donations from Arthur Sackler's side of the family were distinguished by Hyperallergic from the philanthropic contributions that come from the rest of the Sackler family.

The Oxycontin fortune

In 2020, Forbes estimated the Sackler family was the 30th richest family in America. In 2021, the House Committee on Oversight and Reform confirmed that the Sackler family fortune totals $11 billion, made "in large part through sales of OxyContin." Vanity Fair writes that even after Purdue pled guilty to misrepresenting OxyContin's addictive qualities, the Sackler family still continued to profit off of it: "Since 2008, the Sacklers have made $4 billion from Purdue, most of it in the form of profits from opioids."

And as Esquire notes, what made the Sackler family fortune wasn't the drug itself but Arthur's marketing technique. This involved taking an addictive substance and marketing it "as a salve for a vast range of indications." Pain relief was no longer for the terminally ill. It was "a sacred right: a universal narcotic entitlement." And sales representatives were just told to "sell, sell, sell" and were even "directed to lie."

It's possible that the Sacklers may be hiding even more wealth. According to The Local – Switzerland, at least $1 billion in wire transfers were discovered "from one financial institution alone" between the Sacklers and institutions "that have funneled funds into Swiss bank accounts." Ultimately, as Fortune reports, "the true size of the family's fortune is unclear. An earlier court filing said family members received transfers of $12 billion to $13 billion from Purdue over the years, though a lawyer said much of that went to taxes or was reinvested in the company."

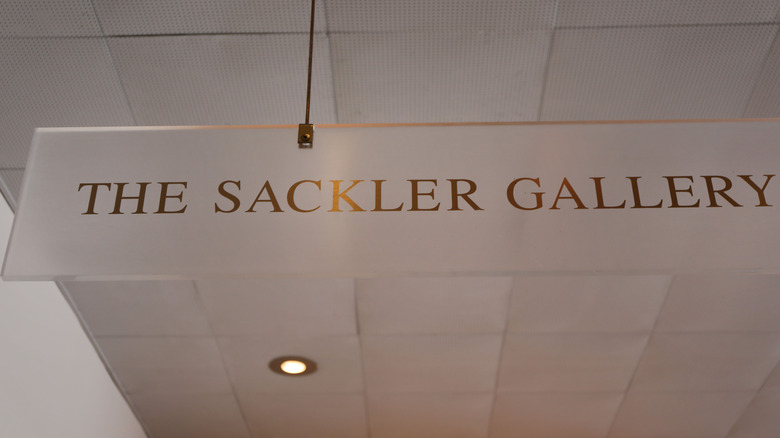

Blood money donations

Over the years, the Sackler family donated millions of dollars to museums and universities around the world. And although some of the donations were given before Purdue Pharma was hit with numerous lawsuits for its role in the opioid crisis, some donations were given in 2018 or later. According to the Associated Press, at least nine colleges and universities, including Yale University, accepted donations from Purdue after the lawsuits were made public, and "some skeptics see the donations as an attempt to salvage the family's reputation." Overall, it's estimated that at least $60 million was given to at least 20 universities worldwide by the Sackler family between 2013 and 2019, "ranging from $25,000 to more than $10 million."

Some institutions like the Tate and the Guggenheim announced in 2019 that they were no longer going to be accepting money from the Sackler family, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art also said that it would be turning down gifts from the Sackler family if they were "closely connected to Purdue Pharma."

And while many institutions have long enjoyed the philanthropy of the Sackler family, many are now wondering whether their names should continue to be displayed, and whether or not it's worth taking the blood money of billionaires.

Naming the Sacklers

It wasn't until 2019 that several Sacklers were mentioned in lawsuits from several states, including New York, Massachusetts, and Utah, which were brought against the family. According to The Guardian, eight members of the Sackler family were named in the multiple lawsuits, one of which was "filed on behalf of 600 U.S. cities and counties across 28 states coast to coast, and eight Native American tribes." This lawsuit alleges that the Sacklers knowingly broke laws in order to profit from peddling Oxycontin. Forbes writes that by 2019, 48 states were suing Purdue Pharma and the Sacklers, and the only reason Oklahoma and Kentucky weren't suing was because by that point they'd "already settled."

The Sacklers named in the lawsuit were: Mortimer Sackler's widow Theresa, Mortimer's three children Ilene, Kathe, and Mortimer D.A., Raymond Sackler's widow Beverly, their two children Richard and Jonathan, and Richard's son David.

Although the lawsuits weren't identical, essentially all of them accused the eight Sacklers named of deliberately pushing deceitful practices in order to profit from OxyContin while simultaneously spreading misinformation about its addictiveness. And while bringing in billions of dollars in profit, the Sackler family is accused of "helping create 'the worst drug crisis in American history.'" The New York Times also notes that the difference between these lawsuits and the one from 2007 is that they underlined "the family's own continued push to sell opioids in more recent years, as the opioid epidemic became a full-blown national crisis."

Purdue files for bankruptcy

In response to all the lawsuits, at the end of 2019, Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy protections. And in 2020, Purdue Pharma pled guilty to three felony fraud offenses. As part of the guilty plea, Purdue Pharma was ordered to pay over $8 billion. However, according to Vanity Fair, right before coming to the $8 billion settlement, "the family moved vast sums out of the company."

Since Purdue Pharma didn't have $8 billion in cash on hand, they proposed dissolving the company and creating a "public benefit company" instead, according to CTV News. Under the proposed settlement, the Sackler family will have to pay only $4.2 billion instead, which many have criticized as an attempt to "shield the wealth of individual Sacklers." The proposed settlement also includes the fact that the Sacklers would be given "immunity from further litigation." There's also roughly 135,000 claims from individual victims and their families, and with Purdue's proposed settlement, they would receive less than $5,600.

While some are fine with the proposal, attorney generals from at least 23 states believe that it "falls short of the accountability that families and survivors deserve," according to The Guardian. Many, including Massachusetts attorney general Maura Healey, believe that this settlement "would set a terrible precedent" and consider it to be an attempt "to sidestep individual accountability."