Lesser Known Heroines Of WWII

Death, the saying goes, is the great equalizer. It turns out that war isn't that far behind, especially when it comes to more modern conflicts like WWII.

While women's roles in WWI were incredibly limited, things started to change the second time around. When the United States waded into the war after Pearl Harbor, millions of women stepped up in major ways. According to the National WWII Museum, around six million went to work on the homefront, while three million joined up with the Red Cross to provide medical support, and 200,000 enlisted in the military. And that's just one country's women.

Once the war was over, it was sort of business as usual. Men came home, women went back home, and it would be decades before real change happened. Still, while women had the chance to go to the front and center — and sometimes, deep into the shadows behind enemy lines — they really took the opportunity to show the world just what they could do. So, let's take a few minutes to remember some of the lesser-known heroines of WWII, because without the contributions of women from all nations, the world today might be a very different place, indeed.

A powerful voice for the German Resistance

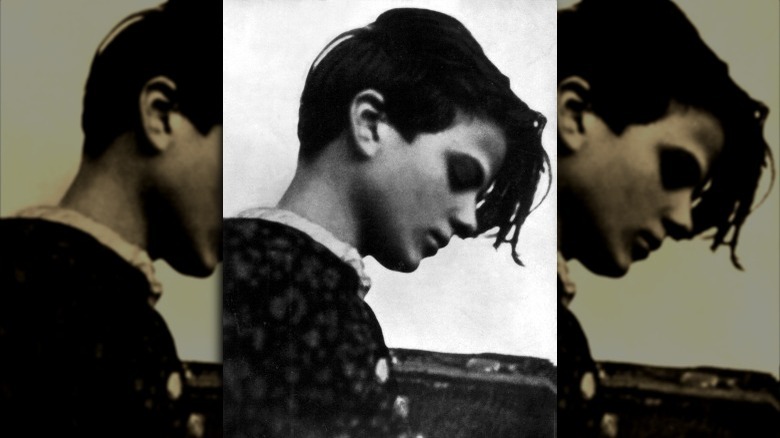

Not everyone was happy to hop in line with the Nazi party and their ideals, and among the Germans who protested the rise of the Third Reich was Sophie Magdalena Scholl. Just 12 years old when the Nazis rose to power in 1933, her family was less than impressed with developments in the Nazi regime. It wasn't long before her brother, Hans, became a founding member of an organization called the White Rose.

The group started as what the National WWII Museum calls a "non-Nazi" youth group, but after outright war came in 1939 and their friends were sent to serve on the Eastern Front, Sophie and her siblings started with publishing and distributing a series of anti-Nazi pamphlets, advocated resistance, rebellion, and sabotage. For years, they did really well, getting their message out to countless other Germans — particularly other students at the University of Munich. Unfortunately, a pro-Nazi janitor saw her distributing leaflets and had both her and her brother arrested.

Their trial lasted just half a day, and at the end, she replied, "I am, now as before, of the opinion that I did the best that I could do for my nation. I therefore do not regret my conduct and will bear the consequences that result from my conduct." She, her brother, and four other members of the White Rose were executed for treason. She was 21 years old when she was sent to the guillotine.

From teacher to feared guerilla fighter

Japan invaded the Philippines in 1941, and when they threatened the lives of Nieves Fernandez's students, well, to say that was a very bad idea is a massive understatement.

That, says Esquire, is because the teacher from the town of Tacloban decided she wasn't going to stand for those kinds of threat, and went full-on guerilla fighter. Dressing entirely in black and at first fighting with only weapons she assembled from the odds and ends she could scrounge, the 38-year-old teacher started killing her way through the Japanese occupiers. Barefoot and alone, she launched full-scale ambushes on her own, took on dozens at a time, and became known as the Silent Killer for her prowess at going straight for the jugular.

She was ultimately credited with killing around 200 soldiers with her hand-to-hand combat, and eventually turned to training others in the village. She built up an incredibly successful guerilla army of 110 fighters, with whom she carried out hundreds of missions against their occupiers. They were so successful, in fact, that by the time American forces landed on Leyte (pictured), they had already driven the Japanese troops from many of the island's villages and freed countless "comfort women." By that time, she had been waging her guerilla war for around three years, and not a single one of her countrymen ever betrayed her for the bounty that was put on her head.

The bicycle-riding Dutch teens who were also deadly assassins

The Oversteegen family was living in the Netherlands when Nazi Germany moved through and set up shop there — and they weren't about to stand for any of it. It was Truus and Freddie's mother who set the example for them. Starting in 1939, they sheltered Jewish refugees fleeing ahead of the Nazi war machine, and when Germany came to them, 14-year-old Freddie (left) and 16-year-old Truus (right) were ready and waiting to join the Resistance.

They were recruited in part because of the fact they looked even younger than they were, and few German soldiers were going to suspect the young Dutch girls, their hair done up in braids as they rode their bikes through the countryside. And that's exactly why they were so good at sabotage, the distribution of anti-Nazi information, and finally, killing. According to History, once members of the Resistance taught them how to shoot, they took it upon themselves to set out on mission to assassinate Dutch collaborators as well as Nazi officers and soldiers. An ambush was one of their favored methods, either from astride a bicycle, or with one sister seducing their target and leading him away from his group.

Unfortunately, neither ever spoke about how many people they "liquidated," as they referred to their assassinations, so much of their history is lost. Freddie died in 2018, two years after her sister.

The chemist who improved life-saving technologies

Katharine Burr Blodgett was born in 1898, and some of her inventions have shaped our everyday, 21st-century life. Computer and television screens, for example, wouldn't be what they are without her, and during WWII, her inventions had a massive impact. The Science History Institute says she was the first woman ever hired by General Electric, and that was an excellent HR decision. Most of her research was built on the work of Irving Langmuir, who was trying to figure out how and why some substances have a tendency to stick together, and some repel. Blodgett took that research and, in a nutshell, figured out how to create a film that could be applied to glass to make it "invisible," creating what ThoughtCo. says was the first truly transparent glass.

It was a military lifesaver, and WWII saw the mass production of things like spy cameras and periscopes that used non-reflective glass to allow troops to look out and around without giving away their position.

She made other incredible wartime advancements, too, just in the nick of time. Her work also led to vast improvements in smokescreen technology, and she also came up with the first reliable method for pilots to de-ice the wings of their planes. Altogether, it's impossible to tell how many lives she saved with her many patents. Blodgett died in 1979, almost 30 years before she was recognized by the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

The activist who opened the door for Black women in the workplace

The National WWII Museum says that there were more than six million women who answered the call to leave home and work in factories, but here's the thing: History says that the vast majority of employers were still making it quite clear that there was still no place for Black women in their organization.

And that's where Mary McLeod Bethune (second from right) came in. The daughter of former slaves, Bethune was born into Jim Crow-era South Carolina. By the time the 1930s rolled around, she was already a well-known advocate for equal rights and serving on what she called FDR's Black Cabinet (acting as advisors on racial matters). When it came to discrimination against Black women who wanted to do their part for the war effort, she definitely advised the heck out of the president. The result was Executive Order 8802, which was signed into law in 1941 and outlawed racial discrimination in hiring practices, particularly in war-related industries. The effects were felt almost instantly, with more than a million people entering the workforce — and that included 600,000 Black women.

The order only got workers so far, though. Black employees were routinely paid much less than white coworkers, and were subjected to extreme racism and sexual harassment. When Bethune died in 1955, she had seen a lot of progress, but knew there was still a long way to go. She wrote: "I leave you hope."

The Quaker who became a codebreaker

A Shakespeare-loving Quaker born in Indiana, Elizabeth Friedman is perhaps one of the most unlikely of wartime heroines. Pacifism and war don't really go hand-in-hand, but she found her own way to save lives — even though according to the Smithsonian, her contributions went unrecognized for a long time, because someone else claimed them: J. Edgar Hoover.

It was actually Shakespeare that got her into code-breaking: She was working on finding "clues" in Shakespeare's works that pointed to their true authorship, and during WWI, her employer offered the services of his team to military work. Fast forward to WWII, years that found her working with the Coast Guard to detect hints of an enemy attack before it happened. That's exactly what she did, sitting down with a pen and paper and getting to work breaking Enigma codes. Those codes uncovered a Nazi spy network operating out of South America, and in 1942, History says she discovered chatter about a planned attack on the Queen Mary. The ship, it turned out, had a $250,000 bounty on it, and her early warning allowed for evasive maneuvers. Around 8,000 lives were saved.

That's just one instance of Friedman's life-saving work as a codebreaker, and it's a story that wasn't told for decades. Hoover continued to attribute the successes to his own FBI agents, and it wasn't until Friedman's death in 1980 that her work started to go public.

She was destined for a pauper's burial until her wartime past came to light

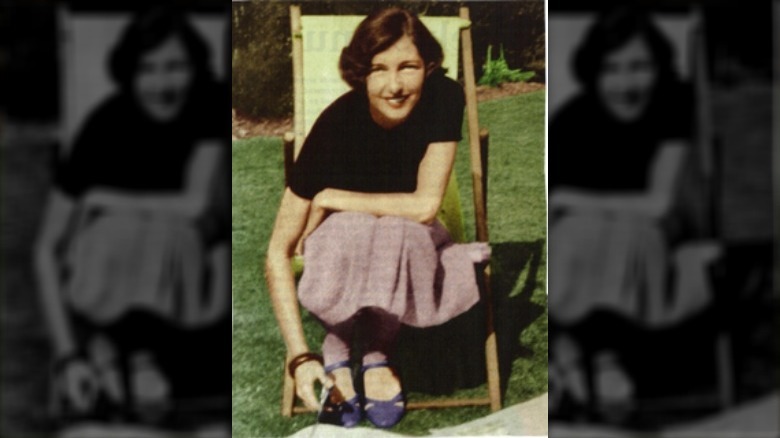

When Eileen Nearne (pictured, in 1940) died in 2010, she was alone in her home. It was days before anyone realized what had happened, and it was only when police arrived that her neighbors realized they had been living alongside a decorated WWII spy. It was only at her death, says The New York Times, that it came out that Nearne had been one of just 39 British women who had been sent to France to help pave the way for the landings at Normandy. Eileen — along with her sister, Jacqueline — both worked with the Resistance, and both forbid speaking of their wartime work. Consequently, it was only after their deaths that their niece, Odile, could start piecing their story together.

According to The Guardian, Jacqueline spent 15 months with the Resistance, often acting as a courier carrying parts for the radios that provided a vital lifeline between the Resistance and the Allies. Eileen followed, and became a radio operator in Paris. Her story wasn't as happy. Discovered by Gestapo agents in 1944, she was tortured then sent to Ravensbrück, where she later escaped and took part in the liberation.

Both sisters returned to Britain after the war, and lived together until Jacqueline's death in 1982. Eileen continued to struggle with the scars of war and retreated into anonymous shadows. Her niece is determined to keep her story from disappearing, too.

The best sharpshooter they ever did see

It was only after Pearl Cornioley — then called Pearl Witherington — volunteered for service that the SOE realized she was one of the best sharpshooters that had even been trained on the range. It was a skill that would come in handy when she parachuted into France and joined up with the Resistance.

Originally, The Guardian says that she was given a cosmetics case, the name Genevieve Touzalin, and a cover story that claimed she was a representative for a company producing beauty products. It gave her exactly what she needed — mobility — to fulfill her real mission: carrying messages for a section of the Resistance run by a man named Maurice Southgate.

When Southgate was arrested and sent to Buchenwald in May of 1944, it was Cornioley who stepped up to take command of the 1,500-odd Resistance fighters. Even as she continued to do everything from organize supply drops to sabotage convoys and railway lines, she dodged the 1m-franc price the Germans put on her head. By the time the war was over, she had personally trained 3,000 guerilla fighters, and her unit was responsible for the deaths of around 1,000 soldiers, the surrender of more than 18,000, and they'd participated in D-Day.

As a woman, she was ineligible for most awards, and when she was offered a (civilian) MBE, she refused: "There was nothing civil about what I did."

The woman who found a home with the French Foreign Legion

When Susan Travers explained her motivation for leaving home and becoming the only woman to join up with the French Foreign Legion, she made it sound pretty straightforward (via The New York Times): "My family was very dull. England was very dull. I wanted adventure. I wanted more action."

And she definitely got it. After spending some time as a Red Cross ambulance driver, she got on the phone with General de Gaulle's office and — within a handful of weeks — she was headed to Africa. Not happy with being a nurse, she got herself transferred to the Foreign Legion, where she became the official driver — and unofficial lover — of General Marie-Pierre Koenig. It was a job that came with insane dangers: When it came time to break through Rommel's circling siege, she was the one leading the charge through artillery fire. Their bullet-ridden car made it to safety, and she later reported (via the BBC), "It is a delightful feeling, going as fast as you can in the dark."

That's about the time her lover's wife showed up, and when Koenig was promoted, he chose the wife and the titles over Travers. She stayed on with the Foreign Legion and drove anti-tank guns through combat in France, Italy, and Germany, then went on to serve during the First Indo-China War. She later explained herself: "I just happen to be a person who is not frightened. I am not afraid."

The Naval teacher who broke barriers

Susan Ahn Cuddy's father set a powerful example for his daughter (pictured, with her brothers). In the late 1930s, he became an independence fighter who took up arms against the Japanese occupying Korea, and died in a Japanese prison in 1938. That left his daughter wanting to do her part, but it wasn't easy — her first application to the US's naval officer's school was declined because, her family says (via NPR), of her Asian heritage.

So, she started as a service member, and it wasn't long before she worked her way through the chain of command to become not just the first Asian-American woman in the Navy, but their first female gunnery officer, training soldiers to use a .50 caliber machine gun. Somehow, she still found time to spearhead a movement that gave female Navy officers permission to wear pants. According to the Naval History and Heritage Command, Cuddy also did it all while facing scathing racism from not just her peers, but her commanding officers — including one who sent out memos warning staff to be careful, because "an Oriental woman" had been seen in the building. Still, she continued to spend the rest of the war giving soldiers the skills that could save their life in battle, and afterwards, she went on to work for the US National Intelligence.

Cuddy died in 2015, and her children had only known the extent of their mother's heroism since 2002, when her official biography was published.

The women who changed everything for each other

The story starts with Lilly Wust (left). Wust, says The National WWII Museum, was married to a member of the Wehrmacht, and when the war started, she didn't really notice much of a difference. She carried on raising her children and it was with her fourth son that things started to change. That's when she was given the Mother Cross for bearing sons for Hitler, and along with that honor came a housekeeper. It was through her that Wust met Felice Schrader (right). Wust began hosting gatherings at her home, and she was falling in love with Schrader. It was a rocky relationship, though, and Schrader would occasionally disappear for weeks at a time.

Eventually, the two married in a secret ceremony, and then Schrader told her: Her real name was Felice Schragenheim, and she was a member of the Jewish Underground. Wust later said (via The Guardian), "I took her in my arms, and I loved her even more."

Wust encouraged her underground activities, but this story doesn't have a happy ending. They had been together for around a year and a half when the Gestapo arrested Schragenheim in 1944. She was sent to Auschwitz and then Gross-Rosen, and died in 1945. Wust survived the war (and hid three Jewish women in her home during the final days of the conflict), but a deep depression led to several suicide attempts. She died in 2005, writing of her lost love: "I dream that we will meet again — I live in hope."

Marina Raskova and the Night Witches

According to History, the Soviet's 588th Night Bomber Regiment was responsible for game-changing damage dealt to high-priority Nazi targets. They were as deadly as they were silent, flying planes made of canvas and plywood that gave little protection from the height, the wind, and the frostbite. The tiny planes were invisible to radar, and the only sound they made was a "whoosh"... before the bombs fell, that is.

The unit became known to the Germans as the Night Witches (Nachthexen), and they were an all-female unit assembled under the leadership of a long-distance, record-holding pilot named Marina Raskova (pictured). Given the go-ahead to select and train her pilots, she did what should have been impossible: turning 400 women (who were given hand-me-down uniforms and obsolete equipment) into deadly, night-flying bomber pilots in just a few months.

They traveled in packs, and were so good at what they did that some of the Germans suspected that they had pioneered some serum that gave their pilots night vision. (That, or they were all criminals used to operating under the cover of darkness.) In total, they flew 30,000 missions and only lost 30 pilots, including Raskova. She was shot down in 1943, and although she was given a state funeral, her unit wasn't called on to participate in the victory parades.

The world's biggest cabaret star... who also spied for the Resistance

Josephine Baker is one of the world's biggest cabaret and vaudeville stars. Born in St. Louis in 1906, Baker went from cleaning homes to the vaudeville stage — and then, says Vogue, it was on to France in 1925. While she was definitely famous for her dancing and her next-to-nothing clothes, it didn't hurt that plenty of institutions warned that her act was scandalous and indecent, accusations that never fail to help promote an artist. When WWII came around, Baker became much more than just a performer — she became a spy.

According to HistoryExtra, the assistant she hired in the early 1940s was actually another French Resistance agent, and they used her fame to travel freely and get access to Nazi officials and the sort of parties where loose lips revealed all kinds of sensitive information — which they wrote on her sheet music and passed along to the Allies. In 1941, she announced that she was taking some time away from the stage to recover from pneumonia in the drier, warmer climates of North Africa... but she was actually setting up a center that would not only allow for intelligence to transfer between North Africa and Britain, but it was also a stopover for Jewish refugees.

Baker later said, "When soldiers applaud me, I like to believe they will never acquire a hatred for color because of the cheer I have brought them."

The princess who became a spy

Noor Inayat Khan was a legitimate, honest-to-gosh princess: Her great-great-great-grandfather was Tipu Sultan, who — way back in 1799 — died in India while fighting against their British occupiers. Ironically, his descendent would die spying for that same country, in spite of the fact that she remained a champion for Indian independence.

Khan was living in Paris when the Nazis moved into France, and when the entire family fled to England, she wasn't about to sit still. First signing up to be a radio operator for the Royal Air Force, she was ultimately recruited by the Special Operations Executive and sent back to France. Codenamed Madeleine, she joined up with a section of the Resistance called Prosper, and according to Al Jazeera, she was only there for a few days when all other radio operatives were captured. Months passed, and she held the communication network together on her own, which is exponentially more impressive with this dire tidbit from the University of London: "The average lifespan of a field agent was just six weeks."

Unfortunately for the agents of Prosper, there were double agents in their midst by 1943. In October of that same year, Khan was arrested, held for 10 months, and taken to Dachau, where she would ultimately be executed, a little over a year after she first parachuted into occupied France.

The Welsh scientist who helped disguise Allied troops

Radar chaff is a military technology that's still in use today, and according to the Smithsonian, it's basically the assembly of strips of reflective material that can completely confuse radar and hide what's really there behind a cloud of messy signals. It was also the invention of a Welsh scientist who was working in Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory (then at Exeter) during the war.

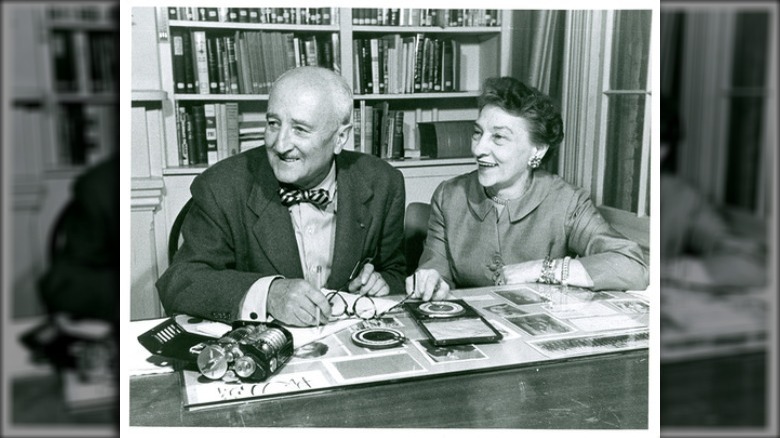

Joan Curran and her partner, husband Sam Curran, were recruited into a team that was tasked with coming up with a way to disguise Allied aircraft — and it was Joan who came up with the idea to use metal strips to recreate the information that radar was picking up on a massive scale. It wasn't until 1942 that she had perfected the system of reflectors that was first put into action during Operation Gomorrah in 1943. That was the bombing of Hamburg, and while the Allies managed to wipe out most of the city, they had minimal losses themselves — and it was a victory that Curran's reflectors were lauded for. The following year, the new tech was used over Normandy as well, to aid in creating false landing zones.

Curran later went to work on the Manhattan Project, but because she was a woman and not eligible for things like awards and degrees, she never got the credit she deserved. She died in 1999, 12 years after finally receiving an honorary degree.

The flight nurse who refused to be just another pretty face

Jane Kendeigh was a flight nurse who was front and center on Iwo Jima (pictured) and, according to the Naval Historical Foundation, her work there earned her what many might have dreamed of: a pass back to the US and a job selling War Bonds. She absolutely didn't want to be anywhere but the front lines, and petitioned to go back to the Pacific.

That's where she became the first Navy flight nurse to land in active combat on the Pacific front, and over the course of about three weeks in March of 1945, she and her team performed daring airborne evacuations of 2,393 wounded soldiers. Each trip from Okinawa to Guam took about eight hours, and flight nurses helmed transport planes that could carry 60 stretchers — and their patients — at a time. The Pacific War Museum says flight nurses like Kendeigh — who was 22 years old when she flew in and out of Okinawa — were not only trained medical professionals, but they were also given extensive hand-to-hand combat training, as it was expected they were going to need to know how to defend themselves.

The flight nurses received little formal recognition for their work. Kendeigh later said, "our rewards are wan smiles, a slow nod of appreciation, a gesture, a word — accolades greater, more heart-warming than any medal."

The real-life intelligence agent who inspired Casino Royale's spy

According to the BBC, the real-life exploits of Krystyna Skarbek inspired Ian Fleming's character Vesper Lynd — and it's easy to see how. The Polish-born Skarbek ended up in England ahead of the Nazi's relentless march across Europe, and was determined to give them the good ol' what-for. Working with the British Special Operations Executive, she headed deep into occupied territory where, according to author Sir Michael Morpurgo (via HistoryExtra), she became well-known for her roles in everything from intelligence-gathering to sabotage missions, often front and center when things started to explode.

Morpurgo has a special sort of respect for her — not only did she work with his uncle in the Resistance, but she saved his life when, after he was captured and taken to a Gestapo prison, she strolled in, demanded to see "her husband," and arranged for his freedom. She, too, did her time being interrogated by the Germans, and got herself released by biting the inside of her mouth, spitting out blood, and suggesting she had tuberculosis. Military History says her history of smuggling cigarettes had given her valuable information about exactly how to get around in Nazi territory, allowing her to gather invaluable information for the Allies and even arrange for the mass defections of her fellow countrymen, recruited unwillingly to the Nazi cause.

Those who knew her say she struggled after the war: she died in 1952, stabbed to death by a scorned lover.