Here's What It Was Like For Prisoners In Ancient Greece

While other penalties including fines and public service are well known among modern people, the one punishment most associated with committing crime is imprisonment. Don't do the crime, they say, if you can't do the time (inside of a prison). But has this always been the case? Has there ever been a time when prison wasn't the go-to move for criminal justice systems looking to punish the guilty? As it turns out, yes. For the ancient Greeks, prison was something that existed, but not as a long-term solution for dealing with convicted criminals.

What, then, was prison like for Athenians (the Greeks we know the most about) during the Classical era (the period we most think about when we say "ancient Greece")? What happened to a person brought up on criminal charges? And if prison wasn't the final destination of a convicted felon, what other kind of punishment could they expect?

Greek prisons weren't really a thing

The answer to the question "what was life like in prison among the ancient Greeks?" is essentially "it wasn't like anything, because prison life wasn't a thing." As Hellenica World explains, imprisonment as a form of punishment for the Greeks was extremely rare, and for the Athenians, about whom we know the most, it essentially didn't exist at all. The Athenians were not interested in going to the effort and expense it would take to build a facility of cells and bars and such in order to hold a convicted felon. They had other, more preferred forms of punishment that they considered much less hassle, on which more in a moment.

This is not to say, however, that no one in ancient Greece was ever jailed. The common motive for imprisonment was to detain prisoners who had not yet gone to trial or who were awaiting execution. For this purpose, Athens seems to have had a dedicated building, referred to as the desmoterion, which is mentioned numerous times by Athenian orators. It is notable, however, that in extant literature, the word never occurs in the plural–which is to say, the Athenians talk often of "the prison," but never about prisons, which seems to indicate how relatively little use they had for such a facility. Even then, it was very common for a prisoner to simply be placed under strict surveillance and not actually put behind bars.

The Greeks saw justice in a different way

The main reason that the Greeks didn't really use prisons as more than holding cells for criminals awaiting execution is that they thought about punishment in a different way than modern society does. As the Center for Hellenic Studies explains, while modern people differ on the motivation for imprisonment as the primary form of punishment imposed by the state, it's generally understood that prison serves either as a deterrent, an opportunity for reform, or retribution for the crime done (each problematic in their own way, but that's another discussion). That is to say, prison theoretically either serves as a way to keep crime off the street, to give people a chance to clean up their act, or to just plain make a person suffer for the wrongs they've done.

For the Greeks, however, the question of why a criminal must be punished was simple: a person had been wronged, they were angry about that wrong, and the state must address that anger by imposing punishment. The point of punishment was to appease the anger of the victim, and in fact, the Athenians did not have a public district attorney to bring criminal cases before the state. In the vast majority of criminal court cases we still have record of (a stunning 96%), the charges were brought before the court by the victim himself. For the Athenians, anger was the basis of law.

Common non-prison punishments

If imprisonment was essentially never meted out as punishment among the Athenians, what sort of punishments were used in order to appease the anger of prosecuting victims? According to the Center for Hellenic Studies, there were a number of potential punishments, depending on the severity of the crime. Commonly imposed sentences included fines, public humiliation in the stocks for a set period of time, a temporary loss of civil and political freedoms such as voting, a total loss of those freedoms, confiscation of property (even to the extent of straight up burning down a person's house), banishment from the city, and, of course, death. Imprisonment, however, was often implemented as a form of punishment to those who had been sentenced to pay fines but could not afford them, but this was generally arrived at by consensus among the citizens involved in the case, and imprisonment was never a punishment passed down by the state.

In fact, exile was the most prominent punishment for serious crimes, approximately on par with the proportion to which imprisonment is used in modern society. Exile served roughly the same purpose: removing wrongdoers from society, allowing citizens to ignore or forget about them and resume a sense of order. When the main goal of your justice system is to mitigate the anger of the victim, removing the criminal from sight is often sufficient.

Class bias in the Greek penal system

Perhaps needless to say, not every person living within the confines of Athens was afforded the luxury of being sentenced to a fine or loss of civil liberties as the consequences of a crime. As in all things, there was a strict class division between land-holding adult males and everyone else. As the Center for Hellenic Studies says, women had no political rights to lose, so it was more common for women convicted of crimes to lose access to religious spaces in place of political ones, being banned from temples and religious festivals, for example. A male non-Athenian residing in Athens could be subject to any of the typical punishments of a male citizen–fines, the stocks, etc.–with the exception of disenfranchisement, as, again, the right to vote is not something they had in the first place. Slaves, of course, incurred the harshest penalties of all, as you would probably expect. If a slave was convicted of a crime, their master might be fined and the slave would be executed. In less severe instances, whippings and beatings would be implemented, while some slaves would be sentenced to be imprisoned in mill houses.

Women, while allowed to witness arbitrations in criminal trials, were not allowed to serve on juries, and if a woman were called as a defendant in a trial, a man would have to speak on her behalf.

The curse of blood-guilt

For the ancient Greeks just as much as for modern societies, the taking of human life–intentional or unintentional–was one of the most severe crimes a person could commit. In fact, the Greeks believed that the stain of guilt borne out by such a crime could taint and poison an entire community if it went unatoned for. As Mythology Unbound explains, this blood guilt was known as miasma, and it was thought of as a sort of curse or god-sent contagion that resulted from the defilement brought on by murder or manslaughter. According to Honi Soit, this guilt tainted not only the perpetrator of the crime themselves, but also their family, neighbors, or anyone in their community who came in contact with them. The only way to remove the stain of miasma was by exiling the wrongdoer from the community so that they can perform an expiation ritual under the sponsorship of a host.

The curse of blood guilt is at the center of a number of prominent Greek myths and dramas, most notably both the Oedipus trilogy and the Oresteia trilogy, in both of which the driving force of the plot is the need to break the curse, which in Oedipus' case involves figuring out what the crime even was first. "Oresteia" is the story of a young man who has to intentionally bring blood guilt upon himself and then deal with the consequences.

The death penalty in ancient Athens

The ancient Athenians had and implemented the death penalty, but it was generally reserved for the most serious of crimes, including murder, blasphemy, and–in one particularly notable example you might have heard of–corrupting public morals. This wasn't always the case, however. As Ancient World Magazine explains, the earliest known written laws of the Athenians, devised by the lawgiver Dracon, proposed death as the punishment for just about any crime (hence our modern term "draconian" referring to a particularly strict set of laws or rules). However, by the time of Classical Athens, even manslaughter was typically punished by exile rather than execution; being removed from all your possessions and social connections in a strange land was considered severe enough.

When the death penalty was carried out, however, there were three typical methods of execution that we're aware of. The first was throwing people into a deep pit, though this was out of fashion by the fourth century BCE. The next, and probably most common, was a little understood device called a tympanon, which was a board of some kind to which the criminal was fastened, and–depending on various modern interpretations–was either beaten to death, exposed to the elements, or strangled in a kind of bloodless crucifixion. The third method is probably the most famous: drinking hemlock, a deadly poison. Despite its renown, this method was incredibly rare, due in part to the great expense of procuring hemlock.

Plato's thoughts on prison

Just because the Athenians didn't typically use prison as a major form of criminal punishment doesn't mean they never thought about it. In fact, one of Athens' most famous thinkers, the philosopher Plato, theorized at some length about that very subject in his last, longest, and generally least liked philosophical work, the "Laws." In this dialogue, as the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains, three men–an Athenian, a Spartan, and a Cretan–work together to try to create a set of laws for a new Cretan colony called Magnesia. Within the work, in a typical Platonic fashion, the three men engage in discussions of ethics, theology, and metaphysics in a way to try to apply them to practical concerns of legislation, such as rules on drunkenness, hunting, and whether or not you can prosecute a suicide.

In Book 9, the discussion turns to the topic of justice and punishment. The Athenian proposes six forms of punishment, including death, exile, and–an innovation for the time–imprisonment. He proposes three types of prisons within the state, each suggesting a different level of severity of punishment: one, a common prison within the city center for general offenders; next, the "House of Reformation," for those whose crimes are judged to be the result of ignorance rather than malice; and finally, a retributive prison in the wilderness, where the offender will spend the rest of their lives in isolation.

Athens' surprisingly small jailhouse

Since we know from the records of various law cases in Athens that there was, in fact, a public building that served as a dedicated prison space, what was that building actually like? Well, thanks to archaeology, we might have a pretty good idea. As Harry's Greece Travel Guide explains, in the southwest corner of the Athenian agora (the Greek equivalent of the Roman forum), there are the ruins of a building that might just have been the Athenian desmoterion. The building is just outside the agora proper, surrounded by workshops and homes. The fact that it wasn't simply another house or workshop is evidenced by its unusual floor plan. Most homes in ancient Greece and Rome featured rooms laid out around a central courtyard, whereas this building is made up of a long hallway with five rooms on one side and three on the other. It seems likely that these were the eight holding cells of the Athenian desmoterion.

One room at the end of the corridor has a large earthenware jar for water, suggesting that it was a bathroom of some kind, while another room has a cistern into which 13 small bottles had been thrown after use. These bottles are believed to have contained the hemlock used in the execution of some criminals. It is entirely likely that this is the very building where Socrates died.

Athenian courtroom procedure

During Athens' classical period, they didn't have a district attorney or any kind of public prosecutor who brought charges against criminals on behalf of the state. Instead, as Famous Trials explains, any citizen could bring charges against someone they felt had wronged them. The complainant would deliver a summons orally in the presence of witnesses, who would then require the accused to appear before a judicial magistrate known as a King Archon at a particular date and time. The Archon would subsequently hear both sides of the issue from the accuser and the accused and decide if the lawsuit was valid under the law. If so, a preliminary hearing would be scheduled, which occurred in front of a magistrate and included a reading of both the charge and the defense, followed by a round of questions from the magistrate.

If the magistrate found the charge to be sound, formal charges and a public trial date would be established. The trial would take place in front of an enormous jury–between 500 and 1,500 male citizens over the age of 30, chosen at random from a pool of volunteers. The charges would be read again, at which point the defendant would have the chance to answer the charges. The jury would then vote: first on the defendant's guilt, and then, in the case of a conviction, on the sentencing, between punishments suggested by both the accuser and the defendant.

Turning a blind eye to jailbreaks

Despite the fact that the Athenians had the death penalty, with the possibility of someone being punished by being thrown down a really big hole, they were generally thought to be exceptionally lenient with regard to actually carrying out the punishments to which someone might be sentenced. The Center for Hellenic Studies explains that the Athenians definitely enforced the death penalty with something of a soft touch. In most cases, even murder, it was generally believed that exile was a harsh enough punishment, so convicts scheduled for execution were often given an opportunity to escape and flee to another country. It was, in fact, expected that convicted felons would break out of prison and escape. It was such an expected part of the process, that there was even an opportunity given to a defendant on trial for murder to simply leave the country rather than risk the death penalty.

Part of the reason that Athens was so willing–and even eager–to turn a blind eye while a prisoner on death row escaped has to do with that concept of miasma, or blood guilt. It's better to avoid having someone's blood on your hands if you can manage it. This is reflected in their relatively bloodless methods of execution–pit, poison, strangulation on a weird device–but the safest way not to bring a blood curse on your city is not to kill someone at all.

Greece's most famous trial

The most famous prisoner and the most famous trial in Greek history is that of the philosopher Socrates, who was put on trial in Athens in 399 BCE. As Famous Trials explains, Socrates' trial is notable because it was a capital trial not regarding murder or any other violent crime, but rather corrupting the morals of Athenian youth through the teaching of philosophy. While most of what we know about Socrates comes through the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, the comedic play "The Clouds" by Aristophanes gives us a pretty good idea of what public perception of the philosopher must have been like: eccentric, dreamy, and condescending (Socrates took these jokes in good humor; he and Aristophanes were apparently friends). Opinions turned darker when some of his former students grew into terrifying tyrants, which suddenly made Socrates' teachings seem more dangerous than charmingly eccentric.

It was the poet Meletus who drew up the official charges against Socrates, claiming that his teachings had a corrupting and undemocratic influence on the youth of the day. The trial took place over the course of about 10 hours in the People's Court in front of a jury of 500 men. His accusers spent their three allotted hours pointing out Socrates' political sins as well as his religious blasphemies, such as saying the sun and moon weren't gods, but rather big rocks in space.

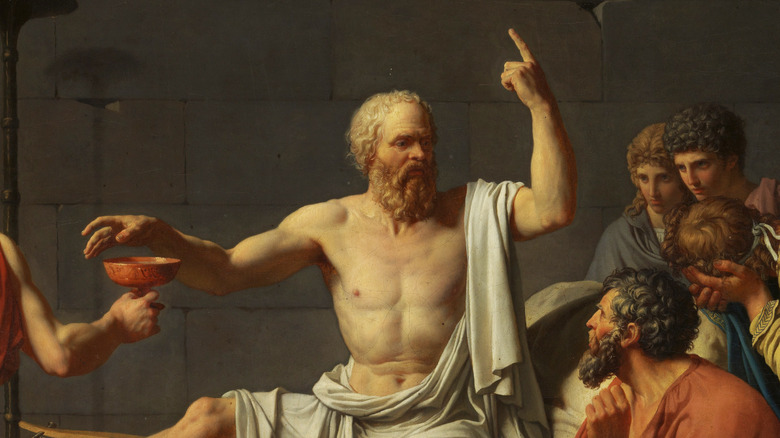

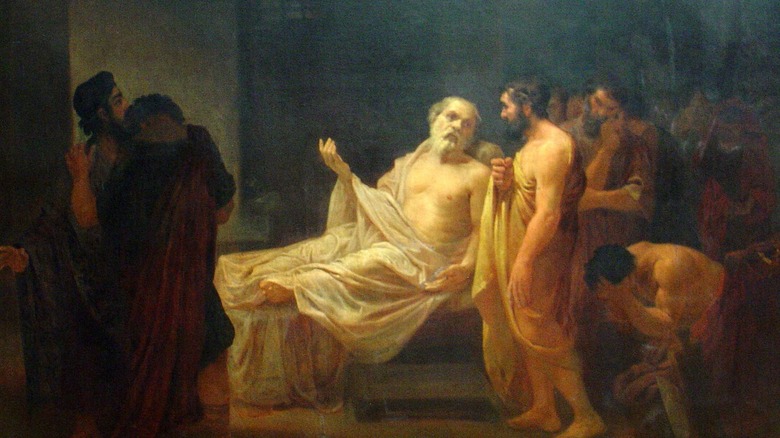

The execution of Socrates

Socrates' response to his accusers is one of the most famous legal speeches in history, with versions recorded by his students Plato and Xenophon, with Plato's being the more famous. This speech is known as the "Apology," but it's important to understand that in Greek, this word just means "defense," because Socrates was anything but apologetic in his response to his accusers, whom he mocks and corrects over the course of his speech. According to Famous Trials, Socrates didn't even bother asking for mercy, as most defendants would have. He said that begging for one's life was a disgrace both to oneself and to the justice system. In the end, Socrates was found guilty, 280 votes to 220.

When the penalty phase of the trial began, it was time for each side to propose a punishment for the now convicted Socrates. Meletus and the others skipped exile entirely and proposed death. Socrates, spiteful of the entire process, suggests that his punishment be that the state buy him dinner every day for the rest of his life. When he was forced to pick a real punishment, he proposed a nominal fine. This mockery of the system upset the jurors more than his crime, so he was sentenced to death by a vote of 360 to 140. Unwilling to flee his fate, Socrates drank hemlock in his prison cell and died in 399 BCE.