The Most Dangerous Queens Throughout History

Most countries on Earth are patriarchal, and women rulers have nearly always sparked controversy, concern, and even fear. Nonetheless, several nations have had queens or empresses, and they have ruled both well and badly. Luckily, even if they made poor decisions, there were either advisers present to curtail some of the worst effects of their actions or a much better successor waiting in the wings, as in the case of Mary I of England and her half-sister Elizabeth.

Being queen gave these women an enormous amount of power, and as such, they had the capacity to make decisions that would impact many people's lives. Ladies-in-waiting, for example, needed to receive Queen Elizabeth I's permission to marry, and when Elizabeth Throckmorton married without said permission, both she and her husband were sent to the Tower, according to Spartacus Educational, though they were eventually released.

Queens could be unpredictable, especially if someone went against them. On the other hand, they could be equally dangerous when fighting to protect their land or people. Many queens have sought to protect their homes, children, or what they considered theirs — some just happened to go about it in a particularly murderous way. Here are some of the most dangerous queens throughout history.

Wu Zetian

Wu Zetian held the Tang dynasty together for over 50 years. According to Women in World History, she was the only woman who reigned as emperor in Chinese history. To do so, she had several branches of the Tang dynasty killed, either through ordered suicide or execution. On the other hand, China went through some of its most culturally vibrant decades with her at the helm.

The Tang dynasty began its reign during the 600s, and women were not subjected to some of the restrictions that they later faced, such as having their feet bound. Wu Zetian was the favored concubine of two emperors, giving birth to several sons. She accused the emperor's wife of killing her daughter and so became empress herself. When her husband suffered a stroke, Wu Zetian created a secret police to keep herself informed. Through them, she imprisoned or killed those who stood in her way, including her husband's former wife. When the emperor died, she navigated her youngest son into power so that she could easily rule through him.

Eventually, in 690, Wu Zetian's son gave up his office, and she became emperor in her own right. Although she had fought fiercely for the throne, once Wu Zetian had it, her rule was fairly normal. She did her best to improve the status of women and began the practice of scholars running the government, appointing them to posts previously held by military personnel. She was eventually convinced to give up her crown to another one of her sons.

Mary I of England

As part of returning England to Catholicism, Mary I burned approximately 300 Protestants at the stake, an act for which she was dubbed "Blood Mary." Since her father, Henry VIII, broke away from the Catholic Church to annul his marriage with her mother, Catherine of Aragon, in order to wed Anne Boleyn, Mary was completely opposed to Protestantism, according to History. After the annulment, Mary lost her place in the line of succession as well as her title of princess — she was afterward referred to as "lady."

Mary I revived heresy laws in order to justify burning Protestants at the stake. The men she burned included Thomas Cranmer, Henry VIII's archbishop of Canterbury. Many commoners were executed in the same way, and some died in prison. Hundreds more fled to Geneva and Germany for protection.

Mary I married Phillip II of Spain, which ended up being an unpopular move. Spain was, after all, a Catholic country, and England's new alliance dragged them into a war with France. England thus lost Calais in that war. Mary had two supposed pregnancies that may have been ovarian cysts (per Doctor's Review) and died in 1558, five years into her reign.

Ranavalona I of Madagascar

Ranavalona I of Madagascar came to power after her husband's death in 1828, beginning her reign by killing all others who could possibly rule. She isolated Madagascar during her 33 years in power, writes Madam Magazine. Ranavalona forced those she suspected of disobedience to her policies to undergo a test which involved eating and vomiting pieces of chicken skin laced with tangena tree poison to prove their allegiance. If they were able to regurgitate all three pieces, they were declared innocent, though this was rare (via OZY).

Progress earlier kings had made was rolled back, including trade agreements with nations like Great Britain. The practice of fanompoana, which was putting poor Malagasy (a people native to Madagascar) to work to settle their unpaid taxes, increased during Ranavalona's reign. Many workers died of hunger as a result of the long distances they had to walk.

Ranavalona forbade Christianity, and those Christians who didn't leave were persecuted and tortured. Her son, Radama II, attempted a coup against her, which failed. Ranavalona died in 1861, leaving the throne to her son (the same one who had attempted to depose her). During her reign, the Malagasy population was reduced by half.

Isabella of Castile

On one hand, Isabella of Castile, by marrying Ferdinand of Aragon, consolidated their two kingdoms. On the other hand, their policies also helped kick off the Spanish Inquisition. Isabella was unpredictable from the start, as she married Ferdinand without the permission of her half-brother Henry IV, the king of Castile, according to Britannica.

When Henry died, a war of succession erupted. Isabella and Ferdinand were not able to take their respective thrones until the king of Aragon died. Afterward, the two fought for a unified Spain. In the process, they conquered Granada, the last Muslim stronghold. It fell in 1492, 10 years after they began the campaign.

Isabella and Ferdinand also began the Inquisition, starting in 1480. Many Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, which turned out to be a grave error in terms the economic impact the move had. Isabella died in 1504, and many of her projects were left for others to take on.

Isabella of France

Isabella of France led an invasion of England that led to her husband's abdication.

Isabella was married to Edward II of England in 1308 at age 12, while the latter was 23. The two would have four children together, but Edward II had a habit of forming deep and intense relationships with male favorites. In 1322, said favorite was Hugh Despenser the Younger, whom Isabella couldn't stand, according to History Extra. Despenser seems to have begun poisoning the king against Isabella. In 1324, Edward II went to war against Isabella's brother, Charles IV of France, and even confiscated her lands.

Isabella negotiated a peace with Charles on Edward II's order. Later, he sent their son, Edward III, to France to swear fealty to Charles, and Isabella now had her son under her protection. She attempted to negotiate with Edward for her return to England, but he refused to agree to her terms, namely booting Despenser from court. Isabella remained in France.

Isabella invaded England in 1326, and Edward II's support crumbled almost immediately. Hugh Despenser was executed, and Edward II abdicated. Though her son had a regency council, Isabella and her supposed lover Roger Mortimer ruled England in all but name for several years. Isabella, unfortunately, seems to have quickly grown as greedy and unpopular as Hugh Despenser was. Edward III launched a coup against his mother in 1330, and Isabella was forced to give up most of her income, as well as lands. She was allowed to settle down as a dowager queen and died in 1358.

Julia Agrippina of Rome

Julia Agrippina, also known as Agrippina the Younger, was the mother of Nero and influenced him during his early years as emperor, especially as she was his regent at first. She took part in a conspiracy against her brother, Caligula, and was exiled in 39 A.D. She was, however, allowed to return two years later, writes Britannica.

Agrippina was suspected of killing her second husband by way of poison, and she married her third husband, Claudius, the same year. She convinced him to adopt her son Nero, from her first marriage, and make him his heir. When Claudius died five years later, it was suspected that Agrippina poisoned him as well.

She became the regent for her son Nero, but that didn't last – Nero eventually had Agrippina put to death. Considering what he must have learned from his mother, it's somehow not surprising that Emperor Nero turned out as he did.

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I outlived both her siblings and a distant relation to become queen of England. Despite taking a hands-off stance on the religion debate, other incidents in her life showed that she wasn't someone to mess around with.

Elizabeth established a solid Church of England during her 45-year reign and also beat back the Spanish Armada, writes The Royal Family. On the subject of Catholicism vs. Protestantism, Elizabeth didn't care for the details of her subjects' faith. However, after conspiracies against her life were found out, Elizabeth did pass strict laws against Roman Catholics. She also had Mary, Queen of Scots, her first cousin once removed, imprisoned for 19 years before signing her execution warrant — Mary had supposedly plotted to take the throne.

Elizabeth also made the decision not to marry. A foreign bridegroom couldn't swoop in and direct England for his own gain, but England also didn't have a prince consort, either, as most people would have thought would be natural. Elizabeth died in 1603 and was succeeded by Mary's son James, who became James I in England.

Catherine the Great

Born Sophie von Anhalt-Zerbst, daughter of a German prince, Catherine the Great led a coup against her husband Peter III in 1762 and ruled as empress of Russia for decades afterward, writes Sky History UK.

Her marriage with Peter was uncomfortable and unhappy on both sides, with both having affairs. According to subtle clues left by Catherine, none of her children were Peter's. Her coup against Peter came less than a year into his reign. He abdicated and died soon afterward.

Catherine the Great further proved her mettle by crushing Pugachev's Rebellion and winning a war with Turkey. Though she had previously considered serfdom unconscionable, after the rebellion, she focused on strengthening it, as Russia could not function without it: Nobles and other owners on whom the crown depended would lose their incomes.

Catherine the Great did not have a good relationship with her son Paul, and she supposedly considered spurning him in favor of her grandson Alexander, writes History. Before this could come to pass, she died of a stroke. When Paul was assassinated five years later, Alexander did become tsar.

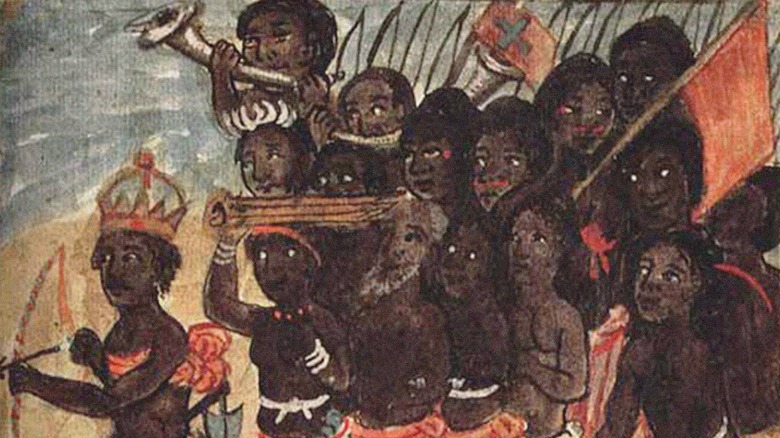

Nzinga

In 1624, Ana Nzinga (also spelled Nazinga) became ruler of Ndongo, which was beset by other African kingdoms as well as Portuguese slave traders. Ndongo was east of Luanda (present-day Angola) and was mainly made up of Mbundu peoples. According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in order to make sure her people would not be captured as slaves, Nzinga allied with Portugal, even being baptized to finalize the alliance. Ndongo therefore had a friend in its fights with other African states.

Two years later, however, Portugal betrayed Nzinga, and she and her people left to go further west to Matamba, where they formed a new government. Her previous state of Ndongo was now governed by Portugal, and Nzinga made sure to stir up rebellion there. She allied with the Netherlands to get Ndongo back but failed.

Nzinga therefore put her efforts toward improving Matamba as a trading state. By the time of her death in 1663, Matamba was just as powerful of a trading partner as Portugal.

Boudica

Boudica, or Boadicea, ruled the Iceni tribe of East Anglia with her husband Prasutagus in the first century A.D., according to History. After suffering a terrible humiliation at the hands of the Romans, Boudica fought back, sacking and burning the cities of St. Albans and London.

Boudica married Prasutagus at the age of 18. When the Romans took over Southern England in A.D. 43, many Celtic kings submitted. Prasutagus, on the other hand, became a reluctant ally, and his territory remained unmolested. When he died in A.D. 60, however, his kingdom was taken. Boudica was flogged in public, and her daughters were raped. According to Roman scholars, Boudica did not take this lying down.

She led a rebellion of Iceni and other tribes who were tired of the Romans. They attacked Camulodunum and murdered whoever they could find. Boudica did the same to London and St. Albans. The Romans eventually mustered themselves enough to fight back, and in the ensuing clash, Boudica killed herself to avoid capture.

Fredegund of Neustria

Fredegund of Neustria was queen of Francia in the later 500s, though she started out as a slave, writes YourDictionary. She developed creative methods of assassination to keep her husband Chilperic interested in her and clear the way for her son to inherit his father's throne. Fredegund was very convincing and was easily able to persuade people to join her plans — and she was vicious.

When Chilperic was at war with his brother Sigibert, Fredegund made things much easier by having her assassins murder Sigibert with poisoned axes. When dysentery killed two of Chilperic's sons from his first marriage, Fredegund attempted to have another killed by having him stay in the region of the outbreak. She also attempted to kill Chilperic's son Merovech, who plotted against his father.

Fredegund's propensity for assassination made her useful to the king — and dangerous in her own right. Chilperic was eventually assassinated, perhaps by her own hand. Fredegund was sent to the countryside by Chilperic's brother, where a government technically ruled by her infant son Chlothar II was set up. It didn't take long for Fredegund to become regent.

Chlothar II eventually became the ruler of a united Francia after Fredegund's death. To commemorate his mother, he had one of her surviving enemies tied to a horse and dragged to death.

Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici was related to popes, and her father was the Duke of Urbino. Within a month of her birth, both her parents were dead by way of illness, writes the Italian Tribune. She was married to the son of King Francis I of France, Henry II, in 1533. She became the dauphine in 1536, after Henry's older brother caught a fever and died. At the time, it was suspected that he was poisoned, though this is unlikely, according to the British Museum.

Though Catherine bore Henry several children, he took mistresses. After Henry's death in 1559, Catherine proceeded to rule France for three of her young sons: Francis II, who died a year into his reign; Charles, who died at age 23; and Henry III, who came into his own as the years went by and eventually took over as king. In 1572, after her daughter Margaret's future mother-in-law died soon before the wedding, Catherine was blamed. Religious tensions between Catholics and Huguenots boiled over in the form of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre just a few days later.

Catherine continued to provide her sons with guidance. Even as Henry exerted himself as king, Catherine kept her skills sharp: She had, for example, a group of female spies known as the "Flying Squadron." In 1589, Catherine de Medici, dowager queen of France, died at age 69.