The Most Dangerous Jellyfish On The Planet

Jellyfish — or sea jellies, as many marine scientists prefer to call these non-fishes — have thrived for over 500 million years. This means they've lived through every single major extinction event in Earth's history and are among the 1% of species that didn't get wiped out (via Scientific American). This also means that jellyfish are the oldest group of multicellular animals around, as jellyfish expert David J. Albert explained in an interview with The New York Times. That's a pretty mean feat, considering how they're literally brainless bags of water.

Most people don't think about any of this when they hear the word "jellyfish," though. Instead, the first thing that comes to mind is their sting. A 2006 paper places the total number of jellyfish stings per year at an estimated 150 million. Admittedly, this is challenging to pin down, since a good number of jellyfish sting incidents go unreported (via Science). And while not all jellyfish species sting, the ones that do can turn a trip to the beach into a total disaster, especially the ones on this list. (Oh, and in case you were wondering, while it belongs to the same phylum as jellyfish, the infamous Portuguese man-o-war is actually a siphonophore — a colony of single-celled organisms operating as a single individual — and is therefore ineligible here.)

Lion's mane jellyfish: big trouble, literally

In 2010, around 150 beachgoers at the Wallis Sands State Park received emergency medical treatment for jellyfish stings, all on the same day. According to a news report from WMUR-9, the victims experienced symptoms ranging from itching, burning sensations to a "vise-like" sensation in their legs. The culprit? A single lion's mane jellyfish, weighing at least 45 pounds and bearing 13-foot-long tentacles.

Experts say that it is the largest known species of jellyfish in the world — unsurprising, given how this jellyfish's tentacles can grow longer than a blue whale (via New Scientist). According to the Smithsonian Ocean Portal, one lion's mane jellyfish specimen measured an astounding 120 feet from the top of its bell-shaped head to the tip of its mane-like tentacles. The University of Melbourne's list of lion's mane jellyfish sting effects include sweating, difficulty breathing, muscle pain, occasional nausea or pain in the abdominal area, and an hour's worth of serious agony. Other recorded effects include both high and low blood pressure, dangerously fast heartbeat, and general weakness, based on a 2020 paper.

There is currently no record of anyone dying from a lion's mane jellyfish's sting, but it's still wise to avoid any sort of direct contact with this animal. The most well-known account of a lion's mane jellyfish actually killing a human being is, in fact, a fictional one — "The Adventure of the Lion's Mane," a short story starring Sherlock Holmes, featured this jellyfish as the unexpected killer.

Stinging cauliflower: extremely rare and dangerous

Certain types of jellyfish such as the moon jellyfish (otherwise known as, appropriately enough, the common jellyfish) are easy enough to find in their known habitats, giving scientists more than enough opportunities to study them. And then there's the stinging cauliflower, a species of jellyfish so rare, there have only been a small handful of confirmed sightings since its discovery in 1880 (via the University of Cyprus Oceanography Center).

Wondering why this species is such a rare sight? Scientists aren't completely sure yet, although Instituto Oikos suggests that it's because it spends most of its time as a polyp. In this stalk-like phase, the animal attaches itself to a coastal reef, nourishing itself until it reaches adulthood and floats around as a full-grown jellyfish (via Te Ara). Confirmed sightings were reported in 1945 and 2014. Some claimed to have also seen it in 2000, 2020 (according to Sputnik News), and 2021 (via the Gibraltar Chronicle).

Ranging in color from pale rose to golden brown, the stinging cauliflower's bell grows up to 3 feet in size, according to the Gulf Coast Research Laboratory. It has about 150 long tentacles and is even known to feed on other jellyfish. Regarded as "highly venomous," experts say its venom can have devastating effects on humans. In other words, it's good this jellyfish isn't seen often — and appreciated (from a distance) when it is.

Nomad jellyfish: a dangerous disruptor

A report from the Daily Sabah cites the European Union's classification of the nomad jellyfish as one of the worst invasive species in its marine territories, while warning beachgoers to avoid contact with this creature. Indeed, this jellyfish that hails from the Indian and Pacific oceans can deliver a massively painful sting. Unfortunately, recent incidents have shown that it doesn't even have to use its tentacles to cause trouble on a wider scale.

The nomad jellyfish has an extremely effective (and rather cruel) method of dispensing its venom. Its mouth arms feature wormlike attachments covered with potent, harpoon-like stinging cells called nematocysts. Once its tentacles touch your skin, the nematocysts latch on. Think that already sounds painful? It gets worse when the stinging cells burst while they're stuck on your skin. Just ask a 15-year-old girl who was unfortunate enough to experience the nomad jellyfish's sting while surfing in Israel, as documented by a 2016 paper in Toxicology Reports. Aside from itching and a hoarse voice, she also suffered from swelling around her eyes, inflammation of her facial tissues, and severe difficulty in breathing.

Individually, nomad jellyfish are already a pain to deal with. As a group, however, they can actually disrupt power plant operations, as they tend to attach themselves to (and subsequently clog) seawater intake systems, to the point where not even filters can stop them (via Haaretz).

Carukia barnesi: a killer no bigger than your finger

Imagine this — you're snorkeling in North Queensland, admiring the Great Barrier Reef. The abundance of colorful life distracts you so much that you don't even notice a tiny jellyfish, no more than an inch and a half in size, drifting towards you. The sting barely registers on your hand, and you quickly forget about it as you swim back up to the surface. Your true ordeal starts 30 minutes later — all at once, you experience a gigantic wave of pain in the form of simultaneous nausea, headaches, intense sweating, joint pain, high blood pressure, irregular heartbeat, and a bunch of other nasty effects. As your companions apply first aid and prepare to take you to the nearest hospital, you silently wonder through the pain, "How can something so small bring you so close to death's door?"

Meet Carukia barnesi, one of a small number of sea jellies sharing the common name "Irukandji jellyfish" (according to a 2006 study in QJM). All Irukandji jellyfish can cause what experts call the Irukandji syndrome, essentially a smorgasbord of serious symptoms like the ones mentioned above. There have even been two reported deaths, both of which died due to a hemorrhage within the skull (as cited by a paper published in 2020). Worse, there is currently no antidote for Irukandji jellyfish venom. Despite the fact that the death rate is relatively low, you're unlikely to ever forget the experience of getting stung by this highly dangerous jellyfish.

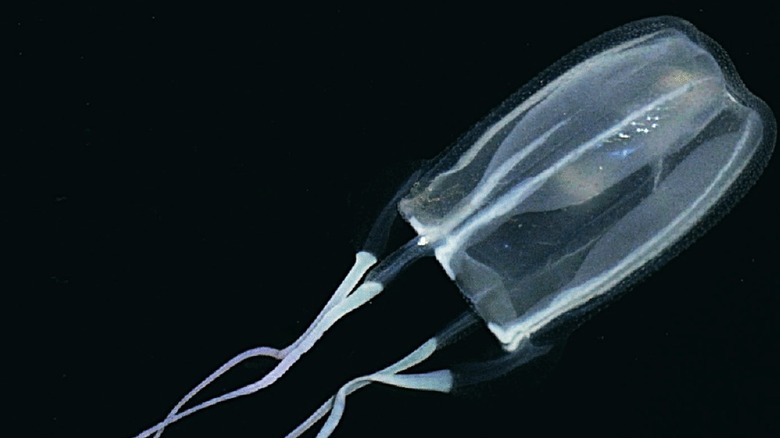

Malo maxima: a threat that's hard to see

A jellyfish species described near the beginning of the 21st century, Malo maxima is one of four sea jellies under the Malo genus, possibly the largest. According to the 2005 paper that announced its existence to the world, it possesses an elongated and robust body flattened at the top, setting it apart from other Malo species. Like other Irukandji jellyfish, Malo maxima is translucent, meaning they're a bit hard to spot underwater (via Great Barrier Reef Australia).

In a 2011 study, experts studied what makes Malo maxima's venom so dangerous to humans. Specifically, it alters the force of the heart's contractions through the left atrium by affecting the body's involuntary danger response. Interestingly enough, it did not seem to affect the right atrium. Malo maxima is suspected to be the jellyfish that stung a healthy 41-year-old surfer and caused him to be placed on life support for almost three days. An odd and still unexplained characteristic of Malo maxima is that it swims less like a sea jelly and more like a fish (via Mindat.org).

Fortunately, even if this species can be difficult to spot, there are signs that indicate its presence in the vicinity. Where there's Malo maxima and other Irukandji jellyfish, sea lice and groups of salps, barrel-shaped marine invertebrates resembling crushed ice, usually show up in the waters as well.

Common kingslayer: a tiny, king-killing terror

The "kingslayer" jellyfish bears its name for an important — and tragic — reason — its discovery in 2007 was the direct consequence of its venom killing an American tourist named Robert King. It's classified under the Malo genus just like Malo maxima, which means it's yet another jellyfish capable of causing Irukandji syndrome. However, unlike its fellow Malo jellyfish, the common kingslayer has four tentacles encircled by tissue matter resembling a halo.

The common kingslayer has been observed to grow up to about an inch and a quarter. As with most Irukandji jellyfish, its sting, while excruciatingly painful, rarely causes death. Upon contact, it shoots its venom into the victim's bloodstream via its dart-like nematocysts.

Interestingly, the Australian jellyfish expert who described the common kingslayer, Lisa-Anne Gershwin, also had a close encounter with this tiny yet terrifyingly dangerous animal. According to Scientific American, the only thing that saved her life was the fact that the jellyfish that stung her was most likely just a juvenile.

Viper jellyfish: the sea jelly named after a snake

As dangerous as its namesake, the viper jellyfish is known to be widely distributed across two archipelagos — Japan and the Philippines. A 2009 paper established its identity as a box jellyfish closely related to the sea wasp, another highly venomous jellyfish.

According to a 2004 study published in Hydrobiologia, this species has eight different kinds of needle-like stinging cells, two of which only smaller individuals have. As of 2009, there were at least three confirmed deaths in Japan due to viper jellyfish stings. The victims died due to heart attack, severe breathing difficulties, and sudden fluid buildup in the lungs.

In a 2009 study, researchers tallied about 40 cases of jellyfish stings in Japan from 2013 to 2017, as an attempt to figure out whether climate change and more interactions between people have led to an increase in jellyfish sting cases. While all of the patients reportedly recovered even without any antivenom administered to them, it's still a lot better to avoid being stung by these potentially lethal jellyfish to begin with.

Upside-down jellyfish: a ridiculous-looking threat

A common thread among many of these jellyfish is that as long as you stay away from them, you won't feel their sting. Unfortunately, Mother Nature enjoys occasionally pulling a fast one, which explains why she gave the ability to weaponize water to such a ridiculous-looking animal — the upside-down jellyfish, named after its tendency to rest upside-down at the bottom of Australia's coastal lakes, lagoons, estuaries, and mangrove forest waters (via the Australian Museum).

The upside-down jellyfish has eight mouth arms that house algae called zooxanthellae. These organisms give the jellyfish's appendages their greenish, grayish, or bluish tint. Their relationship with the jellyfish is mutually beneficial — while its tissue serves as protection for the algae, they sustain their living home by providing it with nearly all of its nutritional requirements.

As mentioned earlier, this jellyfish has the unique ability to turn its shallow, typically meter-deep surroundings into "stinging water." There have been reports of humans emerging from an otherwise normal swim with rashes all over, according to Inside Science. A study published in 2020 in Communications Biology revealed how the upside-down jellyfish does this — through the use of cassiosomes, stinging-cell structures (or "mobile grenades," as the researchers called them) that it releases into the water when it expels mucus, often as a precautionary measure against potential threats.

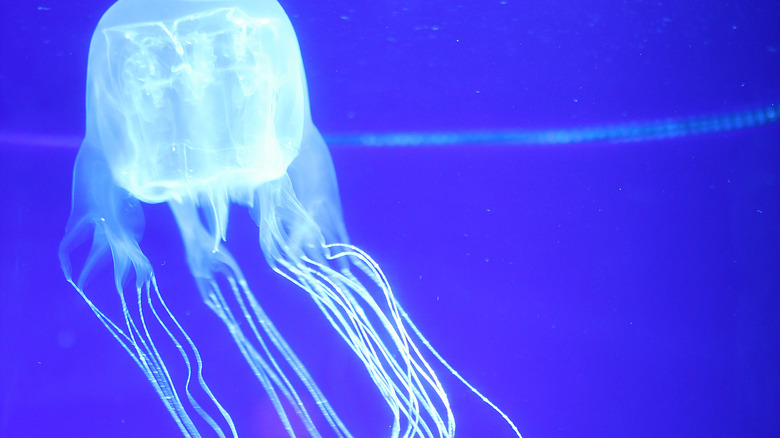

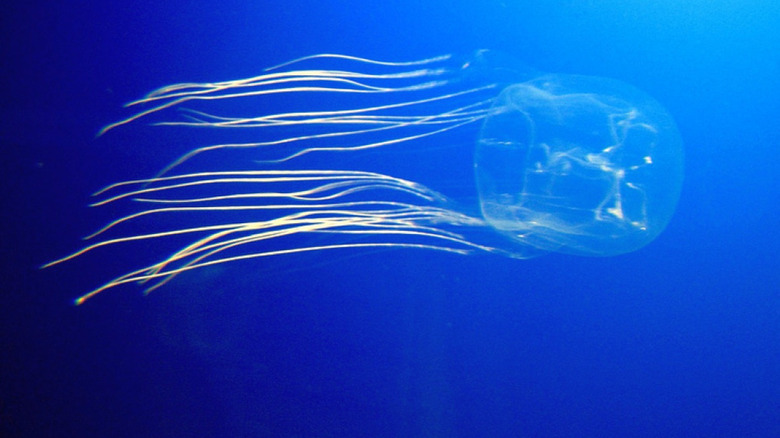

Four-handed box jellyfish: a deceptively deadly sea jelly

Cube-shaped, colorless, and actually kind of cute, the four-handed box jellyfish's pseudo-crystalline appearance masks a fatal secret — a terribly potent and painful sting that is known to be particularly deadly to small children (via the Smithsonian Ocean Portal).

According to a 2002 paper in Toxicon, there were 20 documented cases of people getting stung by the four-handed box jellyfish in Brazil over the course of five years. Eleven years prior, a child died within less than an hour of contact with this deadly jellyfish in the Gulf of Mexico. Meanwhile, the University of Melbourne's School of Biomedical Sciences mentions reports of victims dying in the Philippines.

The four-handed box jellyfish's bell reportedly grows up to 2.76 inches in size, with up to nine tiny tentacles on each appendage. In addition to severe pain, its sting can also cause heart failure and respiratory failure, according to VAPAGuide. People who have survived getting stung sport rashes lasting several months. Fortunately, there's very little residual scarring after they heal.

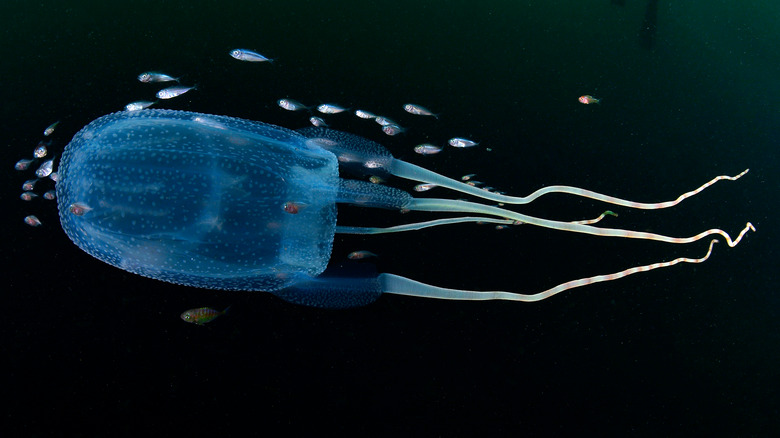

Sea wasp: possibly the world's deadliest jellyfish

Honestly, all that one would need to know about the aptly named "sea wasp" is that it can kill a person in less than five minutes (via the Northern Territory Government of Australia). Widely regarded as the most deadly jellyfish in the world, this incredibly dangerous box jellyfish species has been responsible for about 100 deaths in Australia over the last century, according to the University of California Museum of Paleontology.

The sea wasp is the largest known box jellyfish, with its body growing up to nearly 12 inches in size and weighing a little over 13 pounds (via the University of Melbourne's School of Biomedical Sciences). Despite having up to 60 tentacles measuring almost six-and-a-half feet long, its crystal-clear body underwater makes the sea wasp challenging to spot for swimmers and divers in northern Australian waters. The sea wasp delivers its powerful venom upon skin contact through its tiny nematocysts. A single tentacle reportedly contains "many millions" of these harpoon-like stinging cells.

If you're unfortunate enough to be stung by a sea wasp, you will experience hot, searing pain within a short period of time, quickly followed by skin welting and possibly permanent scarring. In severe stinging cases, the victim may suffer a heart attack after a few minutes, which is the usual cause of death in such incidents. As children have a smaller body mass, sea wasp stings tend to be particularly deadly for them.

Purple stinger: the people-eating salmon slayer

The purple stinger is quite a sight to behold. Its translucent, typically warty body is usually mauve, pink, or yellow in color, with four mouth arms and eight longer tentacles. However, there's a good reason why some people call this colorful sea jelly the "purple people-eater" (via the Australian Museum) — anyone aware of its itchy, painful sting will be wary of touching or even unintentionally coming into contact with it.

Scattered across coastal waters and oceans, the purple stinger is something of an oddity among jellyfish. Unlike many of them, the warts on its bell have the same capacity to sting as its tentacles. Get stung by a purple stinger, and you'll have to endure redness, swelling, rashes, and moderate to severe pain for up to two weeks, as documented in a 2008 paper. A case from 1993 involved the victim exhibiting signs of Guillain-Barré syndrome, a neurological illness in which the victim's immune system mistakenly attacks their body.

Beyond stinging unsuspecting beachgoers in the summer, the purple stinger can also inflict damage on a completely different scale. Both BBC News and the Irish Times reported separate incidents in which large swarms of purple stingers nearly wiped out fish farms' entire salmon populations. Oh, and if that's not enough, experts say that even recently dead purple stingers are still capable of delivering some nasty surprises.

Fire jellyfish: the searing stinger

Notorious among fishermen and divers in Japan for its "fiery sting," the fire jellyfish is one of the largest. The sensory structures within its elongated bell resemble rabbit ears, which is unfortunately the only remotely adorable thing one can say about this sea jelly.

The fire jellyfish grows up to almost 10 inches in height and reaches a maximum width of about 8 inches. Its rectangular, warty body possesses tentacles that grow up to nearly 10-feet long. At night, it typically uses its envenomed sting to catch prey, such as the Japanese anchovy, according to a 2018 analysis of its stomach contents.

Some experts believe that the fire jellyfish's sting can cause the dreaded Irukandji syndrome, which means its victims may suffer a litany of serious symptoms before succumbing to a heart attack. Still, more research on this dangerous jellyfish is required before scientists can determine the full extent of its toxicity.