Lesser Known Heroes Of World War II

When World War II is taught in schools and colleges, there are some names that pop up a lot. These include leaders like Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, and generals such as George S. Patton. But those are just a few names among millions. An almost unthinkable number of people were involved in World War II. In fact, there are so many that the death toll is usually given in estimates. Between 45 and 60 million people died in the conflict, a number that includes the estimated 6 million Jewish people executed in the Nazi's extensive network of concentration camps.

Around 70 million soldiers took part in the conflict; a lot of very quiet heroism and a lot of acts carried out by men facing some of the most horrific situations and scenarios imaginable. These warriors did what they had to do to get through and saved the lives of fellow soldiers and civilians along the way. But not all heroes wear uniforms, and there are many extraordinary stories of bravery in the face of mortal danger by civilians and even children. Here are some names that you may not have heard before, but who are all attached to incredible stories that should not be forgotten.

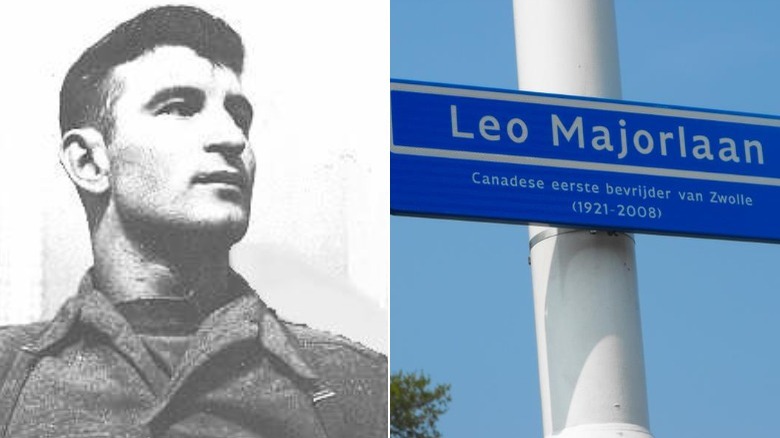

Léo Major

Léo Major was a 19-year-old farmer from Quebec who joined up to fight for the British. His military career got off to a shaky start. He trained as a sniper, but lost sight in one eye to a grenade just after D-Day. Then, he broke three vertebrae, an arm, and both ankles in a landmine incident. Insisting he still had the one good eye he needed to shoot, he headed back to the front.

That took him to the Dutch town of Zwolle, and on April 13, 1945, he and fellow soldier Willie Arsenault were sent into the town of 50,000 on a reconnaissance mission. Arsenault was killed, and after killing those responsible for his comrade's death, Major warned the Germans they needed to evacuate ahead of the arrival of a massive contingent of Allied soldiers. He left, then ran back into town, firing his gun and throwing all the grenades that he could. He also stumbled on the town's Gestapo headquarters and set it on fire. The Germans, believing they were under a major attack, decided the best course of action was to flee.

Today, there's still a street named after Major in Zwolle, and his story is taught to local students. When Major died in 2008, Dutch nationals traveled to Canada for his funeral. Mayor Jan Meijer described him (via CBC) as "a symbol of our freedom."

Henry Mucci

After American forces suffered one of their largest military defeats at the Battle of Bataan in the Philippines, victorious Japanese forces marched their prisoners to a POW camp, where they were subjected to unspeakable torture. The journey is known as the Bataan Death March, and between 10,000 and 20,000 people died along the way. That's where Lieutenant Colonel Henry Mucci comes in. A survivor of Pearl Harbor, he led the 6th Ranger Battalion. PBS reports that one of the men he trained, John Richardson, described the experience as intense, saying, "I thought he was going to kill us."

But it's a good thing that Mucci was hard; the unit was tasked with rescuing the 511 prisoners who had survived the death march and were imprisoned at a camp near Cabanatuan. Mucci and his men made their way through 30 miles of Japanese-held territory, crawling over or past more than 2,500 shallow graves and into one of the most terrifying places: a Japanese POW camp.

They rescued all 511 men, mostly American soldiers who had been prisoners for around three years. Mucci became a hero in his hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and for many years lived in Singapore before retiring to Florida. He died in 1997, aged 88.

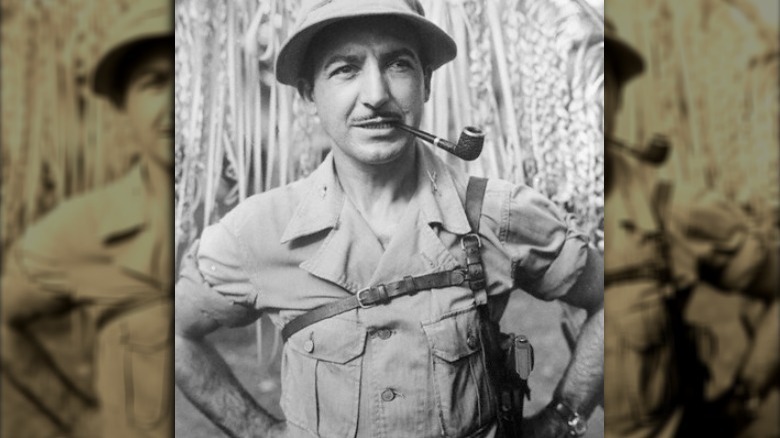

Guy Gabaldon

In June 1944, Guy Gabaldon was a Marine private who found himself in the middle of the battle for Saipan. During that conflict, thousands of Japanese soldiers staged suicide charges against American lines and civilians chose suicide over surrender to the U.S. But Private Gabaldon set out on missions that resulted in him bringing back both Japanese soldiers and civilians alive. He later wrote, "I must have seen too many John Wayne movies, because what I was doing was suicidal."

Gabaldon grew up in Los Angeles, and thanks to a friendship with a Japanese-American family, he'd picked up some Japanese language skills. He put them to use in the battle for Saipan, a part of the Mariana Islands. Often under the cover of darkness, he headed off alone into enemy territory, where he convinced the Japanese to surrender. Promising them that they would be well-treated as POWs, the 18-year-old Gabaldon (right, pictured with some of the people who surrendered) convinced more than 1,000 Japanese soldiers and civilians to follow him back to camp and surrender, including 800 on one July 1944 day. This earned him the nickname the Pied Piper of Saipan.

Gabaldon was wounded and evacuated in 1945, and there was a push to see him awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor after his death in 2006. A documentary about him, "East L.A. Marine," asks whether he had been denied one because of his Hispanic heritage and his opposition to America's Japanese internment camps.

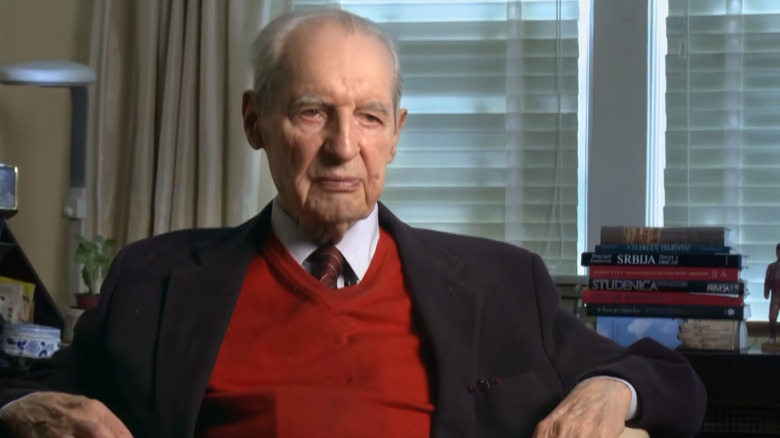

George Vujnovich

George Vujnovich's parents were from Serbia, and that cultural heritage would prove lifesaving for around 500 Allied airmen. In 1944, Vujnovich was an Army officer serving in the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. He led a mission to rescue around 500 Allied airmen who were being hidden by civilians in Yugoslavia's Serbian region. Most had parachuted into unfriendly territory after their aircraft were hit while on bombing missions targeting oil refineries that supplied the Germans.

The solution Vujnovich orchestrated was Operation Halyard. Vujnovich taught three men to dress and act like Serbian locals, and the small team headed into Serbia. There, they passed as locals and helped villagers and stranded airmen to carve a landing strip for rescue planes in the mountains. A series of daring night flights — and even more terrifying night landings — led to the successful evacuation of 512 Allied airmen without casualties.

According to The New York Times, the rescue mission was classified for years, and Vujnovich's war efforts remained secret. But the people he rescued never forgot, and B-24 navigator Tony Orsini, who was among the 512 saved, said years later, "He was a genius in the way he put the plan together. He was a hero." Vujnovich died in 2012, aged 96.

Charles Coward

Charles Coward was a British soldier who was captured and sent to a POW camp in 1940. Three years later, he was moved to the E715 labor camp, a part of the infamous Auschwitz complex. There, in part because of his ability to speak German, he worked as a Red Cross liaison officer and was allowed some free movement within the camp.

As the British POWs had access to Red Cross items, Coward and other prisoners set aside food and medicine, which they smuggled to the Jewish section of the camp. He also helped around 400 people escape Auschwitz by providing Jewish prisoners with the clothes and identity documents of non-Jewish prisoners who had died, before smuggling them out of the camps.

Coward was a first-hand witness to horrible things, but his position allowed him to send letters as he pleased. He started writing to Mr. William Orange, telling him of the details. That name was a top-secret way of addressing a letter to the British War Office. In addition to getting this information out to the Allies, he also testified at the Nuremberg trials. Charles Coward died in 1976.

Joachim Rønneberg

In 1942, the Norsk Hydro plant in Norway had been making heavy water for the agricultural industry for about eight years, and the Allies knew that the plant had been taken over by Nazis, who were planning to make use of the heavy water for Germany's atomic weapons program. A British commando team had been lost on a mission to sabotage the plant, but Norwegian volunteers were prepared to help. After training, a team of 10 Norwegians led by 23-year-old Joachim Rønneberg (memorialized in a statue, pictured above) parachuted into the area. They were delayed by blizzards but skied at night, rested during the day, and reached the plant on February 27, 1943. According to The New York Times, Rønneberg later admitted, "There was no plan. We were just hoping for the best."

Luck was on their side. They crossed an ice bridge over a river to get to the plant, snuck in, set explosives, and activated a 30-second timer. They then made a mad dash away from the exploding plant before embarking on a 280-mile journey to the safety of the Swedish border, all with 2,800 German soldiers hot on their trail.

The plant was destroyed, and it took the Germans four months to rebuild and repair the damage, only for Allied bombers to finish the job completely soon after. Hitler attempted to move the entire operation to Germany, but another attack by resistance fighters ended the possibility of a Nazi atomic bomb once and for all. Rønneberg went on to lead a number of other sabotage missions, was highly decorated for his service, and died in 2018 at the age of 99.

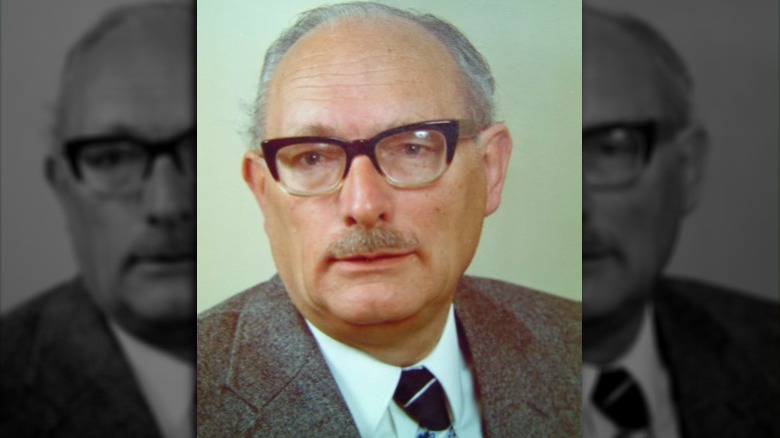

Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz

In the eyes of Nazi Germany, Denmark was seen as an important part of Aryan culture and was a strategically located nation, so when the Danes insisted the Nazis back off their Jewish community, they did. At least, at first: Hitler started to get a little cross with the Danish leadership, which wasn't falling in line as he'd hoped, and ordered the previously untouched Jewish community to be rounded up and sent to the concentration camps. At the time in 1943, Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz (pictured above, center) was a consular official working in Copenhagen for the Nazis.

Duckwitz intervened, warning everyone who would listen about what was going to happen. Danish and Jewish leaders and citizens mobilized quickly, and kicked off an effort that involved millions. Not only did 99% of Denmark's Jewish community survive, but when they returned, they found their homes and possessions waiting for them. Many even found that their pets had been cared for.

It's estimated that Duckwitz's warning saved around 5,000 lives. He remained in the foreign service after the war, before retiring in 1971. He died in 1973 at the age of 68.

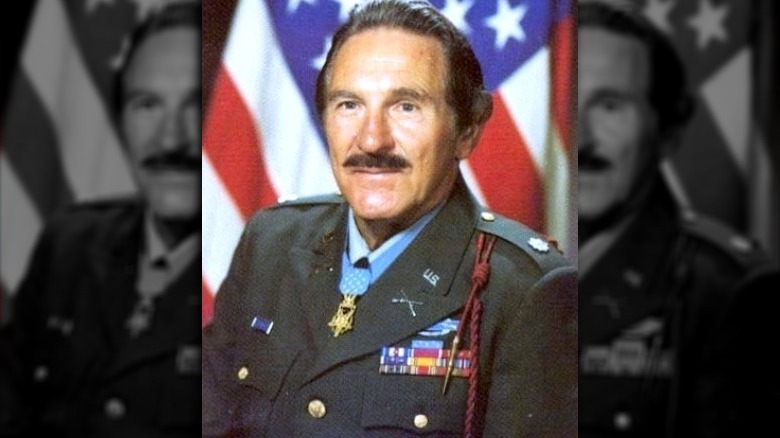

Matt Urban

It would be hard to document the actions of Lieutenant Colonel Matt Urban in full without writing a book or perhaps even making a TV series. Urban has been called the most combat-decorated soldier in American history. His list of honors includes seven Purple Hearts, the Medal of Honor, the Croix de Guerre from France, and 29 medals for bravery.

There's a ton to unpack here, so we'll start with the fact that the Buffalo, New York, native joined up in 1941 and went on to serve in seven campaigns during World War II. Urban was wounded for much of the time, because he was absolutely the sort of commander who led his men up hills and directly charged German soldiers who were dug in and firing all kinds of weapons. That's exactly how he got shot in the throat in Belgium, yet even after that incident, he stayed on the front lines until the Allies secured a crossing at the Meuse River, and only then left the fight.

Due to some misfiled paperwork, he didn't receive the Medal of Honor until 1979, but when he did, there was no question it was completely deserved. Urban died in 1995, after suffering a collapsed lung.

Helmuth Hübener

The Nazis knew exactly how important propaganda was, and in order to help make the spread of their doctrine easier, they created the Volksempfänger — the people's radio. Just like the Volkswagen was the people's car, this radio was designed to be cheap enough that everyone could own one. Unfortunately for the Nazis, it also allowed citizens to pick up international radio.

Listening to international broadcasts in Nazi Germany was a crime, but that didn't stop 16-year-old Helmuth Hübener (center) from tuning in to the BBC in 1941. He was shocked by what he heard — it absolutely wasn't the same story that Germans were being told on national channels — and decided he was going to do something about it.

Hübener had already quit the Hitler Youth after the horrors that unfolded on Kristallnacht. Now, he started writing down what he heard on the international news broadcasts and distributed his pamphlets across the city of Hamburg. He kept it up for months until he was turned over to the People's Court by a coworker, and once he was dragged into court, he continued to speak about the lies they were being told. Hübener was convicted of high treason and beheaded on October 27, 1942. He was 17 years old.

Sir Thomas Peirson Frank

In 1940, the war came to Britain. The Blitz started on September 7, 1940, and London was subjected to a stretch of bombings that hit every night for 57 days. But in addition to the bombs, the capital city had another massive problem: the River Thames, which runs right through the center of London, and has long seen a whole series of flood defenses in force to avoid its waters disrupting the city. Luftwaffe bombs damaged those defenses, threatening the already-ailing city with devastating flooding. Fortunately, Londoners had Sir Thomas Peirson Frank on their side.

Frank was a civil engineer who oversaw the river's flood defenses and the organization of four rapid-response teams positioned at outposts along the river. Outposts were manned 24/7, and at any place there was an attack on the walls along the Thames, teams were dispatched to fix it. The river wall sustained bombing damage in 121 separate incidents between 1940 and 1945, and in each case, Frank's teams were able to reinforce the wall before the river could burst through and flood the city.

The repairs were considered top-secret work for a few reasons. Not only did the government not want Londoners to know how dangerous — and likely — potential floods were, but they also didn't want to draw the Luftwaffe's attention to these potential weak spots.

Marcel Pinte

Sometimes, greatness comes in small packages. That's definitely the case with little Marcel Pinte, who had his name inscribed on a war memorial in Aixe-sur-Vienne (pictured above) during France's 2020 Armistice Day celebrations.

Pinte was born into a family of resistance fighters. His family's farmhouse was a location for Allied air drops in support of the French resistance, and the family also received coded messages from Britain that they passed along to other members of the resistance. That's where little Pinte came in. Nicknamed Quinquin, the child acted as a courier. His small size allowed him to dart behind enemy lines, carrying messages tucked into his clothes.

Unfortunately, this story doesn't have a happy ending. On August 19, 1944, resistance soldiers parachuted into the area. When one of their machine guns accidentally fired, Pinte was caught in the line of fire. He died aged just 6. After his death, the next round of supplies dropped at his family's farmhouse came with black parachutes — a nod to one of the war's littlest fallen heroes. He was given a posthumous promotion to sergeant in 1950, and an official recognition from the National Office of Former Combatants and War Victims in 2013.

Charles Jackson French

The ocean is a terrifying place, but Charles Jackson French took one look at the wide expanse of the Pacific and decided it wasn't going to take his life or the lives of his fellow soldiers. On September 5, 1942, the USS Gregory was attacked and sunk in the Pacific. French, a mess attendant from Arkansas, made it to a life raft with a number of others, but with Japanese forces still nearby, they knew it was just a matter of time before the life raft was sunk or they were taken prisoner.

French was having none of that. He tied a rope around his waist and dove into the shark-infested water. For the next eight hours, he swam, and swam, and swam some more, pulling the raft until they were finally picked up by a friendly landing craft.

But there was no happy ending for French. When he was interviewed much later, his testimony dissolved into tears. While he was featured on a War Gum trading card and traveled the country promoting War Bonds, he ended up succumbing to alcoholism to handle the horrible things he'd seen. French died in 1956, aged just 37. In 2021, veterans groups began lobbying for him to get the recognition and honors he deserved for saving 15 men.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Johan van Hulst

Some of the children of Amsterdam had a guardian angel looking out for them, and his name was Johan van Hulst. In 1943, van Hulst was the principal of a teacher's college located next to a daycare. The children at the daycare had already been separated from their Jewish parents by the Nazis, and van Hulst knew he had to do all he could to keep them from being sent to concentration camps. He made a simple but risky plan: children were passed over a hedge and hidden in the college, before being handed over to the resistance and sent to safety.

Somewhere around 600 children were set free by van Hulst and his network of students, teachers, and daycare workers, who not only spirited the children to safety, but made sure their names disappeared from lists and rosters. Then, in September 1943, they got word that the daycare was closing, and van Hulst was faced with a terrible realization.

According to The New York Times, he said, "You realize that you cannot possibly take all the children with you. You know for a fact that the children you leave behind are going to die. I took 12 with me. Later on, I asked myself, 'Why not 13?' ... All I really think about is the things I couldn't do — the few thousand children I wasn't able to save." Van Hulst died in 2018, aged 107.

Marcel Marceau

Even if you don't know many old-timey performers, you might be familiar with Marcel Marceau (left), a famous French entertainer best known for his mime skills. During World War II, Marceau and his cousin Georges Loinger (right) were responsible for keeping hundreds of Jewish children safe, and Marceau used his mime skills to help turn it into a game for the littlest ones.

Loinger was a Jewish teacher who oversaw a network of French country homes where Jewish children were sent in the hopes of keeping them safe. As Loinger oversaw their continued education, he put a focus on exercise and used other techniques to help prepare the children for a flight across the countryside and into Sweden.

With the help of his cousin, Loinger prepped even the smallest children through play and mime. According to History, Loinger said, "The kids had to appear like they were simply going on vacation to a home near the Swiss border, and Marcel really put them at ease." It's not clear how many children Loinger saved, but it's thought to be well into the hundreds. Marceau also forged identity documents to make Jews look younger so they'd be allowed to flee Nazi deportation. Marceau died in 2007, aged 84, and Loinger was 108 when he died in 2018.

Baron Göran von Otter

After several attempts at taking part in anti-Nazi activities — and being arrested for it — Kurt Gerstein decided that the only way to change things was from the inside. Gerstein, who correctly suspected that his sister-in-law had been one of the victims of the Nazi's euthanasia programs, decided he was going to first become above suspicion. That meant joining the SS, and by 1943, he was a First Lieutenant in the Hygiene Institute. There, he wrote extensively on what he saw, including first-hand accounts of the gas chambers. He took a massive gamble with those writings, passing them on to a Swedish diplomat named Baron Göran von Otter. Gerstein asked von Otter to get the information to the Allies, hoping to reveal just what was going on in Nazi Germany and gain widespread support against Hitler. Von Otter made the report, but Sweden buried the information.

Meanwhile, Gerstein was tasked with making the gas chambers more efficient. That gave him access to massive shipments of the deadly gas Zyklon B, which he regularly dumped, claiming that the containers were leaking or were contaminated.

At the end of the war, Gerstein surrendered to the French. He wrote a full report on all he'd seen in the camps, but instead of using him as a witness as he'd hoped, he was sent to a Paris prison as a suspected war criminal. There, in 1945, he hanged himself in his cell. In 1950, a court ruled (via History) that Gerstein was "not among the main criminals" but placed him among the "tainted." In 1965, he was given a full pardon.

Guy Stern and the Ritchie boys

Guy Stern was one of about 1,400 children who were rescued from Nazi Germany by the Children's Aid Project. The Jerusalem Post reports that he wrote, "I feel unending gratitude to a largely unrecognized group of American Jewish women who saw to it that Gunther Stern took a boat to a harbor in New Jersey rather than a cattle car to Auschwitz."

Safe in the U.S., he wanted to do his part. Stern became one of the Ritchie Boys, a group made up largely of immigrants who were fluent in the languages spoken by the Axis powers that interrogated captured enemy troops and conducted covert operations. The Ritchie Boys were trained at Maryland's Camp Ritchie, where they were taught all about the art of interrogation. Stern's first interrogation experience was at the front lines in Normandy, where he uncovered a wealth of information including details of the diseases spreading through the German army, how well defenses had been repaired, and whether or not the Germans had chemical weapons waiting in the wings.

He was also one of the lead interrogators for Dr. Gustav Wilhelm Schuebbe, who personally murdered 21,000 people. Stern helped uncover the story of how Schuebbe headed up the Nazi Annihilation Institute, where he oversaw the execution of as many as 140,000 people in just nine months. Stern died in December 2023 at the age of 101.

Douglas Lidderdale

When it comes to the most formidable machines on the battlefields of World War II, the German Tiger tank (pictured above) is at the top of the list. The heavily armored machine was nothing short of terrifying, and Churchill wanted to get his hands on one so the Allies could reverse engineer the thing and figure out how to best take them out. According to Forces War Records, he told Major Douglas Lidderdale, "I want you to bring me a Tiger tank. Park the bloody thing outside my front door. Do you understand?"

So, that's pretty much what Lidderdale did. In a daring mission that remained a secret until his son discovered his journals after his death, Lidderdale picked a team and headed to North Africa. It was 1942, and he and his men tried again and again to get a functional tank for the Allies. That didn't happen until April 1943, when they ran up to a Tiger with a jammed turret, took out the crew at close quarters, and then proposed a toast.

The tank didn't make it back to Britain until October, and Lidderdale and his men were chased by the Germans every step of the way. By December, the tank had been completely dismantled and the technology was recycled by the Allies. It was used as the basis of new technology that was used during the D-Day landings at Normandy.

Juan Pujol Garcia

After the Allies turned down Juan Pujol Garcia's offer to spy for them, he went to the Nazis, offered to spy for them, and turned into a double agent who the Allies didn't even know was working for them. Spanish veteran Pujol started feeding Nazi Germany a ton of fake news, and managed to convince the Germans that he was in London spying for them when he was really in Lisbon and didn't even speak English. He was so good that even the British were sent into a panic about the mole they thought they had in London. Pujol built up some serious credibility with Germany, and once the Allies realized how good he was at making stuff up, they brought him on board as Agent Garbo.

Garbo's biggest score came with the creation of a massive British army called FUSAG. He told Germany that FUSAG was the real deal and that they were going to be hitting the Nazis hard. Normandy was just a decoy, he claimed, and the real thing was going to go down at Calais. The Nazis believed him.

After the war, Pujol decided the safest thing for him to do was to fake his own death. It wasn't until the 1980s that historians realized that he had been alive the whole time. He actually died in 1988. Or so the story goes, at least.

Sir Nicholas Winton

One of Hitler's stated goals in his rise to power was to claim Czechoslovakia for the German Reich, and he annexed it in 1938. As one of Hitler's other aims was to exterminate the Jewish race, the residents of Prague fearfully waited. English stockbroker Nicholas Winton heard from a friend in Prague about the situation who implored him to help in some way. Winton had a couple of contacts in Czechoslovakia — aid workers Doreen Warriner and Trevor Chadwick — who helped stage a plan to evacuate Jewish children out of harm's way and into the relative safety of the U.K. His own government wasn't keen on the idea, so Winton repeatedly coerced and intimidated officials to get children their visas, and then found the families willing to foster and sponsor these emigres, including the payment of a £50 fee during wartime. Altogether, Winton put together eight train-based missions known as "kindertransports" and ensured the safe passage and lives of 669 Jewish children.

Winton's heroic efforts remained unknown until 1988, when his wife discovered in their attic a scrapbook of mementos and records recounting the kindertransports. The family passed it along to a holocaust researcher who involved the media, and Winton was booked as a guest on the U.K. show "That's Life." He was surprise-reunited with dozens of the now-adult people he'd saved from the Holocaust.

Giorgio Perlasca

Soldier Giorgio Perlasca believed so strongly in fascism that he fought in an Italian brigade that supported Francisco Franco's fascist takeover of Spain in the 1930s. Franco's government showed its gratitude with a letter promising its support should he ever need it. Perlasca's interest in fascism dissipated when dictator Benito Mussolini joined up with Germany's Nazis and introduced antisemitic laws in Italy. A supplier for the Italian army, but a loyalist to the Italian monarchy, Perlasca was sent to an internment camp by Mussolini's forces in 1943. However, he escaped and headed to Budapest, Hungary, where he'd spent much of his time in the military.

In early 1944, Hungary fell under Nazi rule, and Perlasca knew that Budapest's Jews weren't safe. With his Franco letter in hand, Perlasca went to the Spanish embassy and received a Spanish passport as well as some covert information: The office was processing scores of protection orders for Jews seeking asylum in Spain or elsewhere, and embassy employees were also hiding Jewish people in their homes.

When the Nazis got word, employees evacuated; Perlasca went to the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He convinced the staff that he was the new Spanish consul and had authority over the Jewish would-be refugees, saying they were bound for Spain and if anyone interfered, there would be violent consequences. The Nazis backed off, and Perlasca kept issuing protection letters for Jews to get safely to Spain. Meanwhile, he set up a network of homes in Budapest to secretly house others. Altogether, Perlasca saved the lives of approximately 5,200 European Jews.

Audie Murphy

At 17, Audie Murphy attempted to enlist as a Marine and a paratrooper, but made it into the U.S. Army's infantry after lying about his age. A skilled sharpshooter, he participated in the 1943 Allied invasion of Sicily and Operation Anvil-Dragoon, the 1944 move to reclaim southern France. Across seven weeks of combat, Murphy's group suffered 4,500 casualties.

In January 1945, Murphy, by then promoted to lieutenant, was part of the action to expel Nazis from the Holtzwihr region in eastern France. After Nazis relentlessly hammered the frontlines with six tanks and 250 ground troops, Murphy ordered the rest of his men to hang back and defend because he'd take care of the offense. With just a damaged tank destroyer and a machine, he fought off the Nazi charge from three sides. After he was shot in the leg, he kept going for an hour, killing an estimated 50 Nazi troops and holding off the German advance.

The enemy had to regroup, giving the Allied troops in the area the time they needed to plan a successful counter-attack, getting the Nazis out of that part of France for good. Murphy was awarded the U.S. military's top award for combat service, the Medal of Honor, just one of the 28 he received, including some from France and Belgium. That made Murphy the most decorated American soldier of World War II.

Susan Travers

Briton Susan Travers initially served as a nurse. Hating the work, she joined the French Expeditionary Force as an ambulance driver and served in Finland before abruptly switching jobs again. Following the Nazi takeover of France, she associated herself with the French resistance, and the 13th Demi-Brigade of the French Foreign Legion. An adept driver, Travers safely transported high-ranking officials around battlefields, avoiding mines and shelling attacks, and was rewarded with a promotion to drive for Colonel Marie-Pierre Koenig, the commanding officer of the 1st Free French Brigade.

In May 1942, Koenig was tasked with defending an Allied stronghold at Bir Hakeim in Libya from an attack by Italian and German soldiers, who were seeking access to a nearby strategic point and a Royal Air Force base. German leaders told troops the assault would take 15 minutes; the greatly outnumbered Allies held on for 15 days. All women had evacuated the area except Travers, the only female member of a 3,500-person military contingent, and when supplies ran low it was time to bust out.

Travers led the escape, driving the head vehicle of a convoy at night, but another vehicle hit a landline, exposing the gambit, and Axis troops opened fire. Travers simply drove faster (sustaining damage from 11 bullet holes and shrapnel) and managed to create a hole in the German line of defense through which the rest of her unit followed her to safety.

Lyudmila Pavlichenko

Ukraine-born Lyudmila Pavlichenko had aspirations of being a teacher. Instead, she stepped up to use the skills she learned as an award-winning shooter in her secondary school's shooting club to assist the Soviet Union's Red Army in its fight against the Nazis. While still in her teacher training, Pavlichenko joined a military-sponsored sniper training program, and when Nazi troops invaded the U.S.S.R. — part of the Allied front — she immediately volunteered to help drive them out by shooting as many as she could from long distances.

Pavlichenko's first major assignment came in the Siege of Odessa. Staged in the fall of 1941, she picked off a confirmed 187 Nazi soldiers. As soon as that conflict concluded (with the Nazis victorious), stories of Pavlichenko's prowess had spread throughout the Russian military, and she was given more complicated and dangerous tasks. In October 1941, she was assigned to fight in the Siege of Sevastopol. Lasting the better part of nine months, Pavlichenko consistently fended off the enemy, gunning down a total of 257 German invaders. At one point, she outlasted an Axis-aligned sniper, winning out after a three-day standoff.

After she was wounded in the waning days of the Siege of Sevastopol in June 1942, Pavlichenko became a sniper trainer and is believed to be the most effective female sniper in modern military history. She was the only one of 500 surviving female sharpshooters in the Red Army to receive the military's highest honor, the Hero of the Soviet Union Award.

Edward O'Hare

U.S. Navy pilot Edward "Butch" O'Hare was learning military maneuvers by 1939, and following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, O'Hare's talents were utilized in the Pacific Theater. In early 1942, weeks into the U.S.'s entry into World War II, O'Hare's squadron was assigned to the aircraft carrier the USS Lexington and ordered to head to Rabaul, a Japanese-occupied outpost in Papua New Guinea. On the approach, the American planes were spotted by a scout, triggering the launch of 17 Japanese bombers. The entire first fleet of nine was shot down by anti-aircraft guns.

During the fracas, O'Hare and wingman Duff Dufilho took off and saw the combat firsthand as they went higher, receiving a radio message that the other eight bombers were forthcoming. Both airmen fired test rounds and discovered that Dufilho's guns were nonfunctional, just about when the Japanese planes arrived. O'Hare dove to launch an assault on the V formation, letting most of the bombers pass before he fired at and hit the final two on the right side. And then in the following minutes he shot down two more, all at close range, and well within the line of fire, saving his home carrier and the lives of those onboard.

O'Hare continued to lead air squadrons in the Pacific, and in November 1943 his plane was shot down over the Pacific Ocean and was never found. O'Hare was 29 years old; Chicago's O'Hare International Airport was named in his honor.

Irena Sendler

Under the Nazi occupation of Poland, Warsaw's 400,000 Jewish residents were imprisoned in a tiny urban area — a ghetto — left to suffer from rapidly spreading disease and starvation. After more than two-thirds of Warsaw's Jewish people were transported out and systematically murdered, Warsaw welfare department employee Irena Sendler joined and then headed up "Zegota," a secret Polish-Jewish rescue operation.

Using her connections as a social worker and to other civil servants secretly working with the resistance, Sendler talked her way into permits that let her freely enter the Warsaw Ghetto to assess health issues. She could also freely leave the ghetto, and saw to it that many children were rescued from the horrific conditions, if not an eventual death at the hands of the Nazis. With the aid of around 25 assistants, Sendler got kids out of the ghetto by hiding them under stretchers, inside trunks or body bags, or by directing them to sewers and secret tunnels that led to freedom. After their exit, Sendler arranged new homes for the children and kept coded, hidden records of their real names and families to facilitate reunions after the end of the war.

The Nazis' secret police unit, the Gestapo, arrested and tortured Sendler in late 1943 and sentenced her to death. Members of Zegota bribed the Gestapo to allow her to escape custody, and she resumed helping children find safety. In all, she saved the lives of 2,500 people.