The Aftermath Of The Great Depression Is More Messed Up Than You Know

"The Great Depression," said Vanderbilt economics professor Robert Margo, "is to economics what the Big Bang is to physics." The reactions by governments around the world to the worst global economic downturn in history have become not merely the basis for modern economic theories across the spectrum but also for the political, economic, and cultural realities of billions of people for the rest of the 20th century.

International trends, federal laws, local ordinances, and popular prejudices all steered the world's response to the depression, and its aftermath is still in effect right now. Neighborhoods across the country bear the scars of decisions made in the wake of the Great Depression and left communities still rebuilding from the fallout. The Great Depression has, in fact, never stopped effecting America.

FDR refused to support an anti-lynching bill

Aside from being America's peak period of unemployment, poverty, and hunger, the Great Depression shared the stage with Jim Crow race laws. Laws designed to keep Black Americans from voting, working, going to school, having relationships with non-Black people, and just doing pretty much anything resembling a free life were all over the country in the 1930s but especially among the southern states. They not only discriminated against Americans of African descent in everything from housing to education to medical care, Jim Crow laws also protected people from prosecution for harassing, attacking, and even murdering Black people.

Lynching, the extrajudicial execution of Black people and those who defend them, was a particularly massive problem. According to The New York Times, around 4,000 people were lynched in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Local challenges to these laws were always defeated, often with bloodshed, while the federal government was often paralyzed by partisan gridlock. The American Institute for Economic Research (AIER) described how a federal anti-lynching law was blocked for over 20 years, ultimately becoming "a casualty of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's political ambition."

FDR wanted a third term as president. Because he needed the votes of racist southern Democrats, FDR opposed the federal anti-lynching bill. As heavyweight champion Joe Lewis said at the time, per the AIER, "Roosevelt has been in office for eight years and done nothing about that." It would take another 30 years for Jim Crow to die.

Social Security was accused of discriminating against Black workers

America's Social Security program was designed to provide vulnerable Americans with things like retirement income and disability benefits and is , as the NAACP calls it, "one of the most consequential social programs ever enacted." Unfortunately, the NAACP also says that "the origins of Social Security were rooted in racism." When the Social Security program began, it explicitly exempted domestic and agricultural laborers, which is most of what Black people were allowed to do for work back then. Even as the Social Security Act was being debated, the NAACP at the time warned Congress that the law would leave out most Black occupations and would resemble a "sieve with the holes just big enough for the majority of Negroes to fall through."

For its part, the Social Security Administration (SSA) strenuously denies any racist or racially prejudiced motivations for the law's occupational exemptions. "It was not presumptively racist Southern politicians who moved to delete coverage for these workers," says the SSA, "but northeastern [politicians] ... trying to avoid an onerous task for the Treasury." The SSA points out that those, supposedly not-racist, northern politicians who testified before Congress about those excluded workers weren't actually saying those jobs shouldn't get benefits, but that their inclusion in SSA should be delayed until the Treasury is capable of processing them. The SSA also notes that theirs is a minority opinion, and that plenty of historians agree with the NAACP.

The Depression really made the mafia powerful

Organized crime flourished when the United States banned alcohol in the 1920s. "The big winners from Prohibition were," as the Guardian explained, "of course, the nation's gangsters." A thirsty nation cast their eyes and wallets to the criminals able to quench their thirst. The mafia grew powerful as the New York and Chicago crime syndicates were making upwards of $100 million a year from their underground bars and clubs. According to Business Insider however, American criminal gangs really turned powerful a decade later during the Great Depression.

When all the banks closed, crime was rising, and jobs were scarce, the mafia was often the only source of neighborhood protection, employment, and capital investment. "When the Depression hit, people and businesses couldn't get loans," explained Business Insider. "So the mob took the money they got from bootlegging and started lending it out ..." Aside from often being the only money-lending game in town, the mafia had a competitive advantage over actual lending institutions — they were criminals not afraid of breaking legs to get their money back.

They didn't just loan shark their way into legend, the mafia also benefited from having a lot of cash on hand and, since the depression sent a number of businesses, homes, and other properties into foreclosure, was able to purchase property and businesses all over the country. To put it another way, America's gangsters had their best times "during the most economically trying period of the 20th century."

Redlining was created by the New Deal

In 1933, after four years of increasing economic devastation, America had a serious housing shortage. Millions of people were out of work, millions more had their homes and businesses foreclosed, and thousands of banks were shutting down every year — but the incoming Roosevelt administration was developing a plan to give Americans a home. Well, some Americans at least. The next year, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was born, offering affordable and quality housing to Americans in need, but, said author Richard Rothstein to NPR, "primarily designed to provide housing to white, middle-class, lower-middle-class families."

The segregating of American cities is, in very large measure, the result of systematic prejudices built into the New Deal. The FHA incorporated numerous features to discriminate against Black Americans. "Incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities" said the FHA's Underwriting Manual, guaranteeing Black people could never qualify for home loans or even be considered for certain neighborhoods. Furthermore, the manual actually recommended separating Black and white communities by highways.

Because it is a bureaucracy, and bureaucracies love color-coding, the FHA inscribed its bigotry into their neighborhood maps, designating neighborhoods unqualified for mortgages with the color red. Black neighborhoods were surrounded by red lines, indicating places too dangerous to qualify for a loan, which they weren't. But decades of organized neglect turned it true, and today some of America's worst urban neighborhoods are direct descendants of racist redlining.

The New Deal payed Black workers less

While getting the millions of recently unemployed Americans back to work was obviously a huge priority, FDR was also concerned with getting them paid fairly for their work. His first year in office in 1933, according to an historian with the Department of Labor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had worked on his promise "to raise wages, create employment, and thus restore business" by pushing Congress to pass the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). The act encouraged employers and industries to work with labor unions to set working hours, labor conditions, and wage standards.

While most of the NIRA was declared unconstitutional just two years later by the Supreme Court in a unanimous decision, American unions saw a huge spike in membership, and the National Labor Relations Act, protecting union membership, was passed the same year. However, as the Ohio State Law Journal explains, the new act was designed to exclude certain jobs, like agricultural and domestic employees, and "was well-understood as a race-neutral proxy for excluding blacks from statutory benefits and protections made available to most whites."

Further, says the Department of Labor historian, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 was similarly watered-down. FDR said in that year's State of the Union, largely as a way of appeasing racist southern Democrats, that "no reasonable person seeks a complete uniformity in wages." The law ended up actually forbidding employers from hiring unskilled — Black — laborers who weren't worth the new minimum wage.

Black farmers were robbed of their land by the New Deal

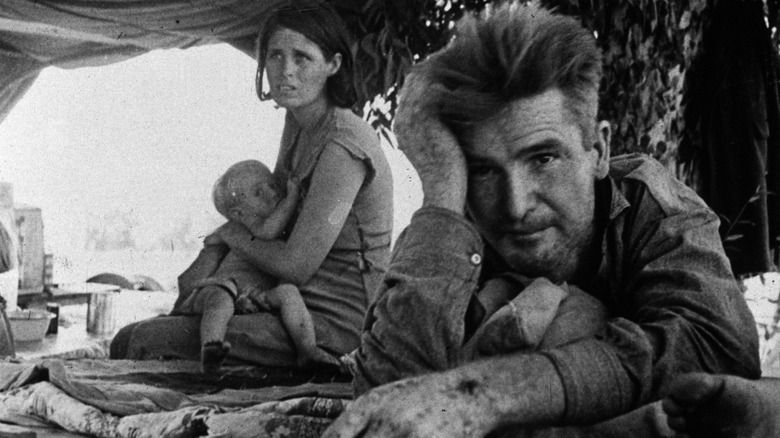

American farmers were exceptionally vulnerable during the Great Depression. Banks closed as markets collapsed, farmers couldn't get loans, prices fell as customers shriveled under their own bankruptcies so farmers earned less, and there were the black blizzards of the Dust Bowl wreaking havoc on thousands of square miles of farmland.

His first year in office, FDR passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act to raise prices so farmers could earn more from their crops and authorized emergency benefit payments for states to allocate to citizens and employees in need. The programs, however, were so rife with racist corruption that, as the Center for American Progress explains, "The number of black farmers in the South decreased 8 percent from 1930 to 1935, while the number of white farmers increased by 11 percent."

One of the grandest projects of the New Deal was the Tennessee Valley Authority. The TVA was created, according to their website, "to address the Valley's most important issues in energy, environmental stewardship and economic development." They went about this with cash payments, reforestation, flood control, and dams. They flooded some 730,000 acres, evicting tens of thousands of people from their homes and farms. The government was accused "of almost criminal neglect of the Negro in the plans of the Tennessee Valley Administration," said a 1934 issue of the Journal of Negro Life at the Virginia Commonwealth University's Social Welfare History Project.

Many people's savings were still gone

While "the entire decade of the 1930s in the United States is often referred to as the Great Depression," says the Library of Economics and Liberty, it affected different countries differently, and America was one of those with an "agonizingly slow recovery." It took a long time for American industries, banks, businesses, and personal savings to recover.

American unemployment topped out at 25%, but it took the mass employment necessary for World War II to finally bring unemployment back down under 10%. For many millions of people, that meant over a decade of living off of savings, borrowing from family, working odd-jobs, and never getting ahead. Owning assets was no guarantee either because, while the stock market crash gets all the attention, property values cratered as well. As a paper from Harvard Business School explains with a quote from a New York City Property Tax Report — "it was not until 1960 that assessments in Manhattan exceeded their pre-Depression level." Home prices dropped by nearly 70% and didn't recover for 30 years.

Fully one third of all American banks closed during the depression, which the more cynical of us may consider a good start, but that's over 9,000 institutions that Americans used for home loans, business loans, and to house their savings. In just one year, says New York Magazine, "depositors lost an estimated $140 billion." That's the life savings of millions of people gone forever.

The birthrate dropped during the Depression

The kids born and who grew up during the depression ended up being called the Silent Generation, in part because there actually weren't that many of them. Birth rates plummeted during the Great Depression, according to the Population Reference Bureau, hitting a record low in 1936, which wouldn't be surpassed for another 40 years.

This wouldn't be too surprising to the analysts at the Brookings Institution who, declaring that "RECESSIONS MEAN FEWER CHILDREN," predicted that the 2020 COVID Recession would also see fewer babies born. A successful prediction it seems as NPR reported that the "U.S. Birthrate Fell By 4% In 2020, Hitting Another Record Low." While it is generally true that people have fewer children in economic downturns, this may not tell the whole story however. The preceding decade of the 1920s saw unprecedented political and economic gains for women, and the Great Depression, notes researchers at the University of Montreal, "attracted young married women 20 to 34 years old in 1930 ...in the labor market."

"The children of the Great Depression learned of necessity to be resourceful," says the Minnesota Historical Society, "wearing hand-me-down clothing, going without luxuries of any kind and, at times, going without meals." The Silent Generation became marked as frugal, reluctant to discard what could be repaired, clipping every coupon, and getting inventive with leftover food.

The war on weed started during the Depression

When Franklin D. Roosevelt became president, the depression had been raging for four years, and there was a lot to do. One of his most popular actions, says the FDR Presidential Library, was to lift the nation's spirits and restore a giant industry by repealing Prohibition. "I think this would be a good time for a beer." In the absence of alcohol however, says an article in Social History of Alcohol and Drugs, many Americans had already begun relaxing with other substances.

National alcohol Prohibition wasn't as revolutionary as many people think today — several states had outright bans as well or great swathes of local bans. Similarly, even though weed had been banned in many states since the 1910s, use went up because people couldn't drink in the 1920s. By the 1930s, alcohol was big money for the government, bringing in billions of tax revenue, says History, and moral crusaders began focusing on banning pot instead. "I anticipated some time ago that ...," said a prominent drug war crusader of the time (per Social History), "... the fiends would turn to Indian hemp."

"Concern about the rising use of marijuana and research linking its use with crime," says PBS, "... created pressure on the federal government to take action." The government launched a noxious propaganda campaign against the "evil weed," supported by strong doses of racism and xenophobia, passed a series of laws, culminating in the Marijuana Tax Act, which effectively banned it.

Americans were very anti-immigrant

There's nothing like an economic catastrophe to bring out the nationalists and straight-up racists in a country. Americans, like many places around the world, were very anti-immigrant during the depression, and many politicians went out of their way to send immigrants — as well as actual Americans — away.

President Herbert Hoover's "attorney general who had presidential ambitions, instituted a program of deportations," said Francisco Balderrama, author of "Decade Of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation In The 1930s," to NPR. Americans needed jobs, after all, and anyone who seemed a threat to those jobs was rounded up or encouraged to leave the country. States passed laws cutting relief to immigrants and descendants of recent immigrants, and the federal government passed laws restricting immigration up to 90%, according to The Atlantic. The private sector was involved to, as multiple industry giants basically "said to their Mexican workers, you would be better off in Mexico with your own people."

"We're talking over 1 million Mexican nationals and American citizens of Mexican descent from throughout the United States," says Balderrama, and, in fact, the majority of the deportees were actually American citizens. Local state agencies were given free reign by, and coordinated with, the federal government to send them to a country that they weren't citizens of, that many couldn't speak the language of, and that was going through its own depression so in no way had the means to help them once they arrived.

Unemployment was solved by World War II

Unemployment peaked at nearly 25% in 1935, meaning at the worst of the depression every one in four people didn't have a job. A third of American banks were closed, and over $1 billion of Americans' life savings wiped out, so the capital to start new businesses and hire new people was slow in coming. FDR's New Deal implemented a number of jobs programs to put people to work, pulled some monetary voodoo on the banks to get money going again, and just spent a lot of money to heal America's broken economy. Even still, after 10 years of dealing with the depression, FDR couldn't get unemployment below 10%.

Then Japan attacked the U.S. at Pearl Harbor, and Nazi Germany declared war. FDR passed the Selective Service Act the year before, "the first peacetime draft in United States' history," according to the National World War II Museum, and some 10 million Americans would join the military before the war ended. Millions more would be working in subsidiary industries, manufacturing material for the military, and unemployment by war's end would dip as low as 1.2%, notes Encyclopedia. Many credit this massive military undertaking for finally ending the Great Depression, but others, like economics professor Frank Steindl in The Independent Review, suggest that "preparations for and engagement in World War II obscured the economy's inherent upward movement," that the recovery was already on the way, and the war actually extended it.

The GI Bill didn't really benefit Black veterans the same

Although it isn't generally thought of it as such, the GI Bill was part of FDR's New Deal legislation. In fact, it would turn out to be one of the most effective. It was intended to help the millions of soldiers sailors, and marines returning from wartime deployment reintegrate into society with housing benefits, unemployment wages, job training, and college tuition. However, while "more than 2 million veterans flocked to college campuses throughout the country," returning Black servicemembers were not accorded the same respect and opportunities, according to The Conversation, "because white southern politicians designed the distribution of benefits under the GI Bill to uphold their segregationist beliefs."

As if racist southern politicians changing the rules wasn't enough, many racist college administrators — North and South — were reticent to accept Black applicants as well. So at a time when "ex-service members made up nearly half of the nation's college students," the vast majority of Black veterans were denied the chance to join their ranks. While the nation's historically Black colleges and universities were chronically underfunded and couldn't accommodate the huge influx of new students at first, they all "welcomed black veterans and their federal dollars, which led to the growth of a new black middle class in the immediate postwar years."