Here's Where We Got The Word 'Genocide'

When President Joe Biden declared April 24 Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, he was the first president since Ronald Reagan to officially recognize that the Ottoman government's attacks, forced death marches, and persecution of Armenians during World War I as a "genocide," reports The Washington Post.

But while mass killings based on religious, social, or ethnic basis have happened repeatedly throughout history, there wasn't actually a word for the crime until 1944, The Washington Post writes. Lawyer Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jew who would go on to coin the term, was only 21 when he saw newspaper reports of the trial of Soghomon TehlirIan, on trial for the assassination of Ottoman leader (and mastermind behind the massacres) Mehmet Talaat (via Genocide: Modern Crimes Against Humanity). In a discussion of the events with one of his college professors, Lemkin was shocked to be told that there were no laws against mass murders. The idea that TehlirIan was on trial for one murder, but Talaat had gotten off without punishment for over a million murders made no sense to him. He later stated in his autobiography, "A nation was killed and the guilty persons were set free. Why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of a single individual?"

Here's what inspired Raphael Lemkin to coin the term "genocide"

Though Raphael Lemkin was inspired to research laws against genocides, he found neither contemporary nor ancient examples prohibiting the practice (via Genocide: Modern Crimes Against Humanity). This inspired him to try to write a new law himself. He outlined not only massive killings on the basis of racial identity, religion, nationality, or any other social or ethnic basis but also the destruction of culture for those groups.

When Lemkin presented his writings in 1933 to a conference of international leaders, it was not well received, particularly by the Germans. When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Lemkin fled to the United States. 49 members of his own family were not so lucky and died at the hands of the Nazis, The Washington Post reports.

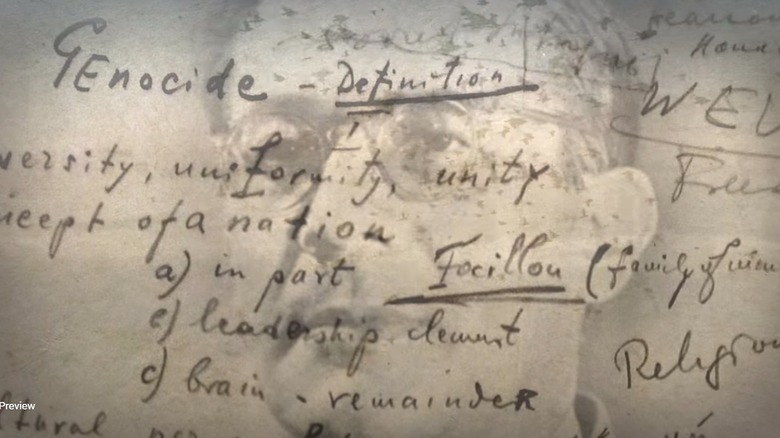

Lemkin recognized the similarities between the Armenian massacre and the Holocaust, and when Winston Churchill stated, "We are in the presence of a crime without a name," Lemkin was inspired to give it one, according to Prevent Genocide. When Lemkin released his 1944 book, "Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress," he coined the word genocide, deriving it "from the ancient Greek word "genos" (race, tribe) and the Latin "cide" (killing), defining it as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group."

Raphael Lemkin left an enduring legacy

After World War II, Raphael Lemkin wrote an essay in American Scholar, pushing the United Nations, to "enter into an international treaty which would formulate genocide as an international crime, providing for its prevention and punishment in time of peace and war." He was successful, and the first instance of the crime of genocide was recognized in 1946, and later, on December 8, 1948, with the adoption of the "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide," (via The United Nations ).

Lemkin featured heavily in Samantha Powers' 2002 book, "A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide," where she detailed Lemkin's struggles, and the reluctance of American politicians to get involved when genocides occur in the world, E-International Relations writes. The book won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-fiction (via The Pulitzer Organization).

The movie "Watchers of the Sky" premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2014, the BBC notes, telling the story of Lemkin's struggle to recognize genocide. Director Edet Belzberg used Powers' telling of Lemkin's story as a jumping-off point for the film, profiling her in it as well, and featuring what few photos of Lemkin they could find, interspersed with interviews and archival footage.

When Lemkin died in 1959, he was still relatively unknown and "penniless," writes the BBC — yet he has clearly not been forgotten.