Messed Up Things That Happened During The Renaissance

According to James Franklin of the University of New South Wales, the Renaissance is popularly known as the period when Europe emerged from a millennium-long "dark age" and rediscovered science, art, and literature of the Greco-Roman world. Latin of the ancient Roman writers returned as the literary language of the day. Artistically, the Renaissance gave us painters such as Michelangelo, theologians such as Erasmus and Martin Luther, and scientists such as Galileo.

This, at least, is the myth Renaissance painter Giorgio Vasari offered, but it really was only true for those of means. For the average person, life continued to be dangerous and unpredictable. Threats of invasion, religious war, disease, and sugar all played a part in producing an uglier side to the Renaissance.

Muslim pirates struck fear into coastal communities

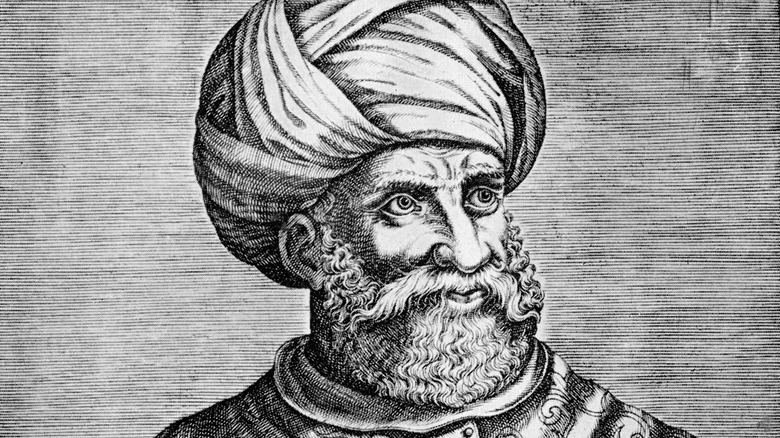

Europe's incredible cultural progress and wealth served to make it a target for foreign attackers. Mediterranean and Atlantic coastal communities faced the omnipresent threat of pirates from North Africa. Although many of the pirates were Muslim, the situation was more complicated than meets the eye.

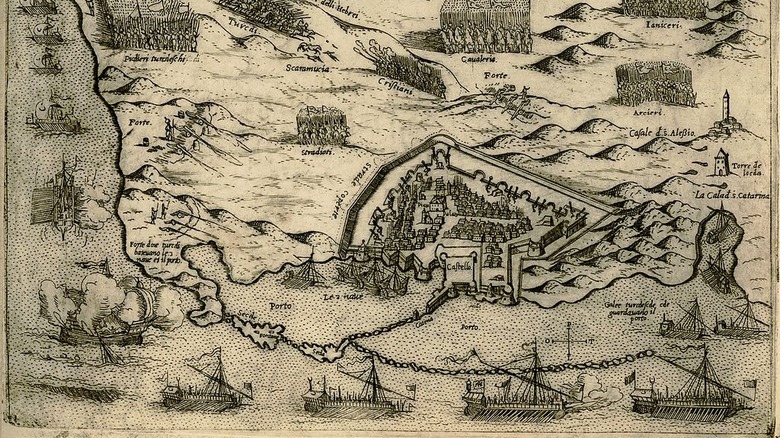

North African pirates frequently targeted Catholic Italy, Spain, and Malta in search of captives to sell in Ottoman slave markets, although Moroccan pirates managed to reach Iceland in 1627. The most infamous pirates, Hayreddin Barbarossa and his brother, Uruç Ali, achieved notoriety in the Mediterranean for sacking the Balearic Islands, robbing Spanish treasure ships, and successfully attacking Southern Italy. Ironically, Barbarossa found his greatest ally in Catholic France, which provided Ottoman pirates with safe havens to launch attacks against France's Hapsburg enemies. As noted by Paul Cassar, Christian states such as the Knights of Malta also captured slaves by raiding Muslim shipping, although their captives were mostly men.

The vicious cycle of raids and counterraids cast many into a life of misery for Christians, Muslims, and Jews alike. Simon Webb notes that although wealthy captives could ransom themselves, most men ended their lives as galley slaves in Ottoman or European navies. Women, however, suffered the worst. Captured women were usually sold into sexual slavery, disappearing into the harems of their wealthy owners never to be heard from again.

For Balkan Christians, Ottoman rule cost them their children

Byzantine rule in the Balkans crumbled in the late Middle Ages, leaving the Ottomans to fill in the vacuum. While the Ottoman army was unmatched, the loyalty of its armies was always in doubt because the sultan depended on his subjects to supply him with troops. Because they had their local and personal loyalties, the sultans devised a cruel but ingenious way to create their personal military units.

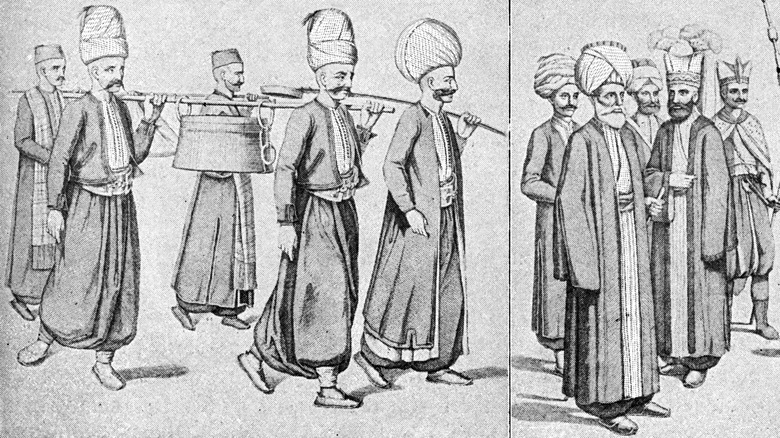

According to Boston College, beginning with Murad I, Ottoman sultans recruited slave soldiers into elite personal units called janissaries. While slave soldiers such as mamelukes already existed, the Ottomans were more discriminatory. Every four to five years, the sultans levied the "blood tax" upon their Christian subjects in the Balkans, Anatolia, and the Caucasus. According to the Encyclopedia of the Orient, Christian rural families gave up one male child under the age of 2. The children were converted to Islam and educated to serve in the janissary units and in the Ottoman bureaucracy. Although they were slaves, they were paid and given preferential treatment for appointments in the Ottoman bureaucracy because their primary loyalty was to the sultan. The janissaries had no other family ties other than with the sultan and their fellow soldiers, making them the perfect force to buttress the sultan's position.

The blood tax was the Ottoman Empire's cruelest tax upon its Christian subjects. Perhaps the worst aspect of the system was that the janissaries fought against their co-ethnics, who bore the brunt of Ottoman aggression. The practice peaked during the Renaissance and then gradually died out by the 18th century, as Muslims sought entry into the janissaries as a means of advancement in the imperial bureaucracy.

The Ottomans were legendary for their cruelty

Historian Edward Freeman, writing in 1877, noted that the Ottoman reputation for brutality had survived into his day. In fact, the Ottomans were well-known for using massacres to achieve their aims, making them the terror of Central Europe and the Mediterranean.

Among the Ottoman Renaissance massacres, two epitomize the cruelty they were capable of. In 1480, an Ottoman army massacred the inhabitants of the city of Otranto in southern Italy for refusing to convert to Islam (Pope Francis canonized the defenders in 2013). After the fall of Famagusta in 1571, the capital of Venetian Cyprus, the Ottomans massacred the city's Christian population after it had surrendered, saving the worst for the Venetian commander, Marco Antonio Bragadin. According to historian John Julius Norwich, the Ottoman commander had Bragadin's nose and ears cut off, and he was dragged around the city alive. Bragadin was then tied to an Ottoman ship's mast, flayed alive, and sent to the sultan as a war trophy.

As Christian states organized opposition to the Ottomans, some hit back with their own gruesome punishments. Vlad Tepes, for instance, impaled invading Ottoman forces in revenge for his time in Ottoman captivity. Thus, the Ottomans were not unique in their cruelty. Europe's Christian rulers could be quite nasty themselves.

And so were the mercenaries Christian rulers employed

Although the Ottomans were often depicted as cruel Muslim barbarians, Renaissance Europe's Christian rulers were often just as brutal. The privatization of war through greedy mercenaries allowed rulers to commit far greater atrocities. Men such as the Italian condottieri and the German Landsknechte were employed to fight wars and carry out massacres on behalf of their paymasters, bringing pain and suffering wherever they went.

According to historian Alexander Lee, the life of a Renaissance mercenary was savagery. In Italy, the condottieri's preferred tactics were to avoid fortified cities and burn and loot the vulnerable countryside. Mercenary commanders tended to be unpleasant people who resorted to violence and civilian massacres to achieve their ends, leading to enormous suffering in northern and central Italy during the 15th century.

Mercenaries were especially dangerous when they were not paid, as the papacy found out to its detriment when 14,000 Protestant Landsknechte sacked Rome in 1527. The German Landsknechte were so brutal, that it was said that the devil did not allow them into Hell when they died. The 1527 Sack of Rome epitomized the attitude of Renaissance mercenaries. For them, profit came first, no matter the cost, without any scruples.

The Reformation brought religious war to Europe

Europe hardly needed more problems. Between constant wars and Ottoman invasions, the continent was plenty unstable. Augustinian monk Martin Luther, however, had other ideas, accusing the Catholic Church of grievous corruption in his 95 Theses in 1521. History notes that Luther refused to recant his accusations before the Imperial Diet in the city of Worms. Yet, Luther seemed irrelevant. Rome had successfully suppressed most heresies it faced in the Middle Ages, so Luther was expected to meet the same fate.

Ironically, it was the papal candidate for the throne of the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick III of Saxony, who protected Luther and ensured the survival of the Reformation. According to Reformation 500, Frederick kidnapped Luther and protected him inside Saxony from imperial attempts to arrest and kill him. Frederick eventually accepted Lutheranism on his death bed in 1525. His brother, John, however, was already Lutheran and saw the new creed as an opportunity to undermine Hapsburg authority.

As the Reformation spread, other North German states and all of Scandinavia joined the Protestant fold. Much of this was ultimately political. The American Interest notes that Lutheranism served as a convenient excuse to confiscate the Catholic Church's landholdings in Central Europe and Scandinavia, enriching their rulers and providing them with money to oppose Habsburg dominance. As the issue of the Reformation became more political than religious, a series of vicious wars erupted that led to one of the stranger, but by the standards of its time, progressive settlements of the Renaissance.

The solution was not tolerance but more suppression from both sides

Two events sped up the inevitable march towards religious war. In 1530, the Lutheran Church was officially established under the Confession of Augsburg. The next year, the states of Saxony and Hesse united several states following the Augsburg Confession into the League of Schmalkalden to prevent the Catholic emperor Charles V from eradicating Protestantism by force. Despite Hapsburg power, the League of Schmalkalden grew strong enough to challenge imperial authority on the battlefield in 1546.

Although Charles defeated the league in 1547, a second uprising backed by Catholic France in 1552 defeated imperial forces. The resulting 1555 Peace of Augsburg adopted the principle of cuius regio eius religio as the solution to the religious conflict. According to the Davenant Institute, this Latin phrase meant that the religion of the ruler (Catholicism or Lutheranism) would be the religion of his subjects. His subjects were elected to conform regardless of personal convictions. Dissidents were allowed a grace period to sell their properties and leave for a state that shared his beliefs. In practice, this meant for instance that a Bavarian Protestant would have to find a new home in North Germany, while a Catholic would not be officially welcome in a city like Hamburg or Lubeck.

While the Peace of Augsburg was certainly not an epitome of religious tolerance, for its time, it was incredibly forward thinking. Problematically, though, the settlement did not consider the status of reformed churches, such as Calvinism, Zwinglism, or the French Huguenots. Per the Christian History Institute, the exclusion of Calvinism would lead to instability not only within the Holy Roman Empire but also England and France. Eventually, the tensions led to the Europe's bloodiest conflict thus far, the Thirty Years' War.

Witch trials reached their zenith

The Reformation brought witch-hunting to Northern Europe, where it flourished for two centuries. According to Historic UK, the medieval Catholic Church did not have a uniform rule on witchcraft. Some was considered pagan superstition, and other times, it was considered to be the devil attacking humanity. This changed in 1486, when the Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer, against a background of plagues, wars, and eventually, Protestantism, wrote "Malleus Maleficarum" ("The Hammer of Witches"). Kramer argued that the problem of witchcraft had increased throughout Europe and merited harsher penalties, especially for women.

The unstable climate of central and northern Europe during the Reformation ignited large-scale witch hunts and trials, particularly in southern Germany and the British Isles. Per Deutsche Welle, thousands of men, women, and even children were tortured and executed on these charges. Although scholars generally agree that many of them were innocent, the tortures endured led many to confess either from sheer mental exhaustion or from hope of escaping execution.

The tortures used varied from region to region but were brutal. The BBC writes that in the British Isles, the accused were deprived of sleep indefinitely until they broke down and confessed from exhaustion. Historian Camille Naish notes that often suspects were humiliated, including with the "breast ripper," being sat upon red-hot stools or upon sharp metal horses called chevalets.

According to Medieval Science and Philosophy, the rise of Enlightenment Rationalism brought an end to the witch craze. Once the belief in magic died out among educated elites, witchcraft, which required the use of magic to exist, could no longer be considered a crime. Although some isolated witch killings persisted into the 19th century, the practice as a whole disappeared by 1750 and was removed from European penal codes.

Jews were not spared discrimination either

Jews were caught up in the religious battles of the Renaissance as well. Following the completion of the Spanish Reconquista in 1492, Jews were expelled from Spain. Many fled to Italy for shelter, where they encountered varying attitudes among the Italian states.

While Pope Alexander VI Borgia welcomed Spanish Jews to Rome and even fined local Jews for objecting, Venice was not so generous. The republic segregated Jews into the ghetto, which was an alternative to complete expulsion — a compromise because of Jews' niche in the local economy, per historian Catherine Fletcher. Although Jews were known as moneylenders in Europe, all of Italy's largest banks, such as Monte Paschi di Siena, were Christian owned. Jews instead carved out a niche as small lenders to commoners, upon which many livelihoods depended. Venice recognized that expelling them would negatively impact the daily economy, so the republic opted to restrict them instead.

The University of Washington described conditions in the ghetto as poor. In the Roman Ghetto, founded in 1555, the inhabitants were barred from holding well-paying jobs, had to wear special clothing (also worn by prostitutes) identifying their status as Jews, and were occasionally made to participate in Christian rituals. Faced with these restrictions, My Jewish Learning notes that many continued their journeys east towards the Ottoman Empire in hopes of finding better conditions to live their lives. Some, however, remained in Rome, where their descendants still live today.

The papacy had become corrupt and political

While war raged in Northern Europe, corruption had entrenched itself in the papacy. Italy's fabulously wealthy states competed for control of the papacy, the key to politically dominating Catholic Europe. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, although the papacy had always been political (the pope was the temporal ruler of the Papal States), in the Renaissance, it became nakedly political and secularized.

The two most notorious Renaissance families to hold the papacy were the Florentine Medici and the Aragonese Borgia. Renaissance papal corruption, frequently cited as the principal cause of the Protestant Reformation, was legendary. Pope Alexander VI Borgia, for instance, at minimum, had four children by a mistress with whom he maintained relations during his papacy. One of his sons, Cesare, was already archbishop of Valencia at age 17, posts that today are reserved for accomplished and respected priests. The Medici were no better. According to Christian History Institute, Pope Leo X was accused of taking part in sinful activities such as masquerade balls, selling salvation, nepotism, and excessive spending.

Such corruption within the church drew the attention of reformers such as Martin Luther and Erasmus of Rotterdam. These men openly wrote against the papacy's sins, with Erasmus even penning a dialogue called "Julius Excluded." This tract described Pope Julius II being barred from entering heaven. Eventually, the Catholic Church did clean itself up, but it took the bloody Protestant Reformation to finally push it in that direction.

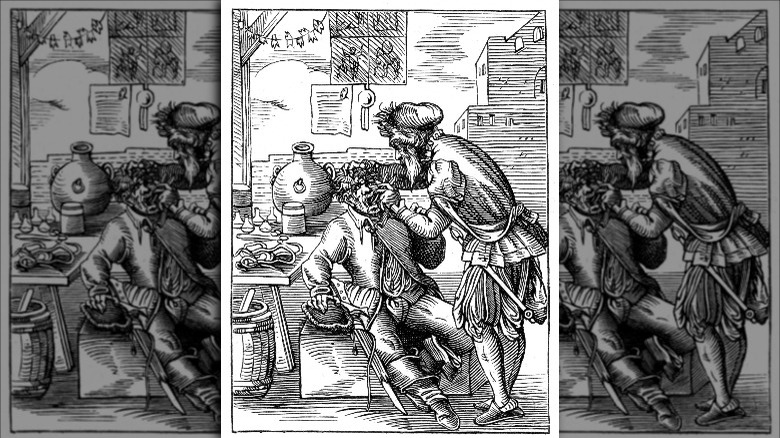

Rotten teeth were a sign of nobility

Renaissance life, for all the glamor, was still hard for the average person. The nobility, on the other hand, saw an increase in their standard of living as the Columbian Exchange and Portuguese Voyages of Discovery introduced new luxuries from Asia and the Americas to Europe. According to Saveur food magazine, the most important prestige product in Western history was sugar. Made widely available through the plantation economy of the New World, Europeans used it as a sweetener and for producing baked goods, which gradually became daily staples among the upper classes. However, this brought in new set health problems.

In the Middle Ages, the main dental problem was the wearing of teeth. According to "The Story of Food," the widespread consumption of sugar among the upper classes introduced the problem of rotten teeth. Dentistry Review names one famous Renaissance personage with poor dental hygiene, Queen Elizabeth I of England, but the problem was found throughout Europe. Today, rotten teeth are rare in modern societies because of access to dental hygiene products and services. Anyone with rotten teeth would likely be too poor to afford dental care. In the Renaissance, though, rotten teeth were a mark of nobility and prosperity. According to Marge de Mello, lower class Renaissance women, especially in England, would dye their teeth black to make them appear rotten. While it is strange that something so unsightly would be considered attractive then, it is a reminder that beauty standards change.

How messed up was the Renaissance?

The Renaissance, like most other periods had an ugly, unsavory side behind the grandeur. However, the ugly side of the Renaissance should not be dismissed as purely bad, because ultimately, something positive did come of it. As the Thirty Years' War delivered untold suffering to Central Europe, some began to ask themselves if another way of governing existed that could sideline religion in favor of secularism and reason.

The ugly side of the Renaissance in a way resulted in the society Americans enjoy today. In response to the bloodshed of religious wars and monarchical tyranny, the Enlightenment created concepts such as constitutionalism, property rights, and natural rights. According to the University of Idaho, John Locke's treatises, among others hugely influential to the American system, were developed as a response to these tragedies, urging religious toleration in a multi-confessional society. Therefore, despite the enormous suffering ordinary people suffered during the Renaissance, a seed was planted that would eventually blossom into the system that would forge the modern world.