The Untold Truth Of Bo Diddley

On his acclaimed 1977 album "Hard Again," Muddy Waters, the immortal father of the Chicago blues, famously sang, "the blues had a baby and they named it rock 'n' roll." In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Waters and his innovative use of the electric guitar paved the way for a new generation of musicians who would use the blues as a jumping-off point for an energetic new sound that would cross the color line. Driving this rock 'n' roll revolution were charismatic Black performers like Chuck Berry and Little Richard, whose raucous rhythms and lyrics became the soundtrack for a generation.

Yet, no artist is more responsible for rock's primal, driving beat than Bo Diddley. Adopted and raised by his mother's cousin, Diddley was active in his church's orchestra as a child, but the call of the blues would send him in a far different musical direction. Inspired by such artists as John Lee Hooker and Waters, Diddley made his way to Chicago, where he got his start busking on street corners.

By 1954, Diddley had joined Chess Records' stable of blues all-stars. His first single, "Bo Diddley," backed with "I'm a Man," rocketed to No. 1 on the rhythm and blues charts, laying the foundation for rock 'n' roll and inspiring generations of artists ranging from the Rolling Stones to George Thorogood. With a career spanning six decades, Diddley's influence on rock, pop, R&B, and hip hop is immeasurable. This is the untold truth of Bo Diddley.

Young Bo Diddley was a violin virtuoso

Like many early rock 'n' roll musicians, Bo Diddley was a self-taught guitarist. Influenced by Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker, he developed a style all his own. In his own words, he played the stringed instrument "like a drum." Nevertheless, in terms of formal musical training, he did have a leg up on his competition.

As detailed in the New York Times, 8-year-old Diddley, born Otha Ellas Bates, saw a boy playing the violin and begged his adoptive mother, Gussie McDaniel, to buy him one. A poor widow recently relocated to Chicago in search of a better life, McDaniel couldn't afford the expensive instrument. McDaniel's church, Ebenezer Missionary Baptist, located on Chicago's South Side, began a collection to buy Diddley a violin and pay for lessons. Under the tutelage of teacher O.W. Frederick, Diddley quickly developed an aptitude for the instrument and eventually wrote two violin concertos. He would play violin until he was 15, when a broken finger ended his days as a classical musician.

In 1987, Diddley recalled his childhood foray into classical music to Rolling Stone. "I used to read all this funny music, like Tchaikovsky," Diddley said. "But then I didn't see too many black dudes playin' no violin."

Young Diddley was also a multi-instrumentalist who played trombone and drums in the Ebenezer church band. However, once he heard the blues, all other music would fall by the wayside.

Bo Diddley's sister bought him his first guitar

Although a young Bo Diddley was proving himself to be a classical violin prodigy and skilled drummer in his church's band, his true musical love was the blues. Longing to become a famous bluesman like his idol John Lee Hooker, he got his first guitar in 1940, shortly before his 12th birthday. "My sister Lucille bought me a guitar for Christmas," Diddley told the BBC in the 1996 documentary series "Dancing in the Street: A Rock and Roll History." "Mama Gussie wasn't too happy about it, but I got it. Like all parents, [she said], 'You ain't gonna play that in here, boy!' I didn't see anything wrong with it, so I taught myself."

Diddley credited his unique guitar style to what he considered a physical limitation. ”I couldn't play like everyone else,” Diddley told the New York Times. ”Guitarists have skinny fingers. I didn't. Look at these. I got meat hooks. Size 12 glove.” Unable to pull off the fluid, pentatonic leads of his heroes, Diddley concentrated on developing a driving rhythm sound. Explaining his distinctive, percussive approach to the guitar, Diddley told the BBC, "I'm a rhythm fanatic. I play the guitar as if I'm playing the drums — that's the thing that makes my music so different. I do licks on the guitar that the drummer would do."

No one's really sure where Bo Diddley got his name

Bo Diddley was born Ellas Otha Bates on December 30, 1928, to teen mother Ethel Wilson in McComb, Mississippi (via The New York Times). He never knew his father. Diddley was raised by Wilson's cousin, Gussie McDaniel, and her husband Robert McDaniel. When Robert died in 1934, Gussie moved her family to Chicago to be closer to family. Although Diddley was never formally adopted by "Mama Gussie," his name was changed to Ellas Bates McDaniel out of fear that he wouldn't be accepted into Chicago schools unless McDaniel was recognized as his legal guardian.

The origins of Ellas McDaniel's stage name, however, are far more complicated than the circumstances of his childhood. As detailed by the National Blues Museum, the name had been used by numerous Black vaudeville performers prior to his birth. It's thought that it's derived from the diddley bow, a simple, one-stringed instrument of African origin.

Diddley variously claimed that he took the name from a harmonica player he saw as a child, that it was an insult hurled at him by schoolyard bullies, and that it was a nickname he picked up as a teenage Golden Gloves boxer. In an interview with music historian Richie Unterberger, harmonica player Billy Boy Arnold stated that the name came much later, when Arnold explained the unfamiliar term as a name for a "comical, bow-legged type of guy" to record producer Leonard Chess, who then applied it to Diddley and his first recording.

The Bo Diddley beat birthed rock 'n' roll

Characterized by what has become universally recognized as the "Bo Diddley beat" — a syncopated rhythm with origins in both the Yoruba drumming of West Africa and the handclapping music known as hambone developed by enslaved African Americans (via Rolling Stone) — Bo Diddley's music is imbued with a driving quality that separates it from that of his early musical peers such as Chuck Berry. The Bo Diddley beat would become an indelible part of rock music's vocabulary, found in songs ranging from Buddy Holly's "Not Fade Away" to the Who's "Magic Bus" to U2's "Desire."

As the originator of one of the most copied rhythms in music, Diddley denied any influence when it came to his famous beat. "That's something that I stumbled upon," Diddley told musician and comedian Dan Aykroyd in an interview featured in the book "Elwood's Blues." "People keep trying to tell me it sounds like hambone ... That's a lie. If you write hambone down, it's not the same notes ... But I'm glad I wrote what I wrote. I had no idea what I was starting."

One person who knew exactly what Diddley was starting was pioneering deejay Alan Freed, who first used the term rock 'n' roll to describe Diddley's music. "I was the first son of a gun to get called rock 'n' roll because they didn't know what to call it," Diddley told James Haskins, author of "Black Music in America." "I was the one who started the whole thing."

Bo Diddley employed women in his band

Bo Diddley was ahead of his time in ways that went beyond his infectious rhythms and over-the-top showmanship. In the male-dominated music scene of the 1950s, Diddley regularly employed women in his band and would continue to do so to the end of his career.

When Diddley's guitarist was drafted into the army in 1957, Diddley replaced him with Peggy Jones. As recounted in "She's a Rebel: The History of Women in Rock & Roll,” by Gillian G. Gaar, Jones was already an accomplished guitarist with her own band, the Jewels, when she met the pioneering rocker. Jones' guitar skills and ability to replicate Diddley's signature rhythms earned her the nickname Lady Bo. Appearing on many of Diddley's greatest hits, including "Who Do You Love" and "Hey Bo Diddley," Jones left Diddley to concentrate on the Jewels in the early '60s but returned for Diddley's 1987 European tour.

Following Jones' initial departure, Diddley recruited guitarist Norma Jean Wofford (above with Bo Diddley and Jerome Green). Giving her the stage name "the Duchess," Diddley falsely claimed Wofford was his sister in an effort to fend off amorous fans and band members. Wofford left the Bo Diddley band in 1966 to raise a family.

From the '80s until Diddley's death in 2008, musician Debby Hastings served as both bassist and musical director of Diddley's band. Hastings, who also played with such legends as Willie Dixon, Chuck Berry, and Jerry Lee Lewis can be heard on Diddley's Grammy-nominated album, "A Man Amongst Men."

Bo Diddley wrote a 1950s pop favorite

Guitarist McHouston Baker and singer Sylvia Vanterpool, known professionally as Mickey and Sylvia, struck music gold with their 1957 hit "Love is Strange." Going all the way to No. 1 on the R&B charts, the crossover hit was also a top-20 hit. Best remembered for its slinky opening guitar riff and its endearing spoken word section, the song has since been covered by many artists, including Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers, and Wings, notes Song Facts. In 1987, the song got a second life when it appeared in the film "Dirty Dancing."

The hit song was originally co-written and recorded by Bo Diddley and his guitarist Jody Williams, in 1956. As recounted in Vanity Fair in 2006, Mickey and Sylvia's version came with Diddley's blessing after the duo approached him about recording the song after a Washington, D.C. gig. Due to a record label dispute, Diddley is credited as Ethel Smith, the name of his then wife. Diddley's original recording of "Love is Strange" was released in 2007 as part of the box set "I'm a Man: The Chess Masters, 1955–1958."

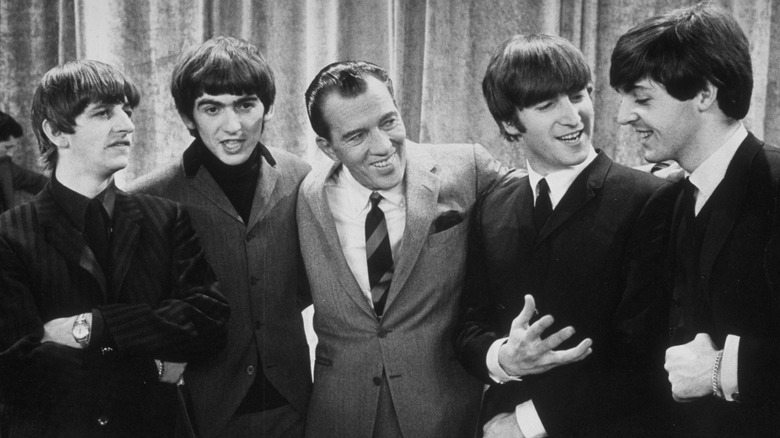

Ed Sullivan banned Bo Diddley from his show

In the 1950s and '60s, there was no surer sign that an artist was on their way to the top than an appearance on the "Ed Sullivan Show." Host Ed Sullivan had an eye for talent and an uncanny ability to spot trends in music. Middle America got their first exposure to Elvis, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones via Sullivan's long-running Sunday night program.

Sullivan, however, was a stickler for rules and propriety and, as Bo Diddley found out in 1955, wouldn't hesitate to ban an act for violating his wishes. Although Diddley's story of his ill-fated appearance on Sullivan's show varied over the years, the commonly accepted version is that the rock 'n' roller was scheduled to perform the Tennessee Ernie Ford hit "Sixteen Tons." Through either misunderstanding or downright defiance, Diddley hit the stage and launched into his self-titled hit. The crowd went wild, but Sullivan was incensed. Backstage, Diddley caught the brunt of the host's wrath. ”[Sullivan] says to me, 'You're the first black boy' — that's a quote — 'that ever double-crossed me,”' Diddley told The New York Times in 2003. ”I was ready to fight. I was a dude from the streets of Chicago, and him calling me a black boy was ... bad ...' They pulled me away from him because I was ready to fall on the dude.”

Sullivan was true to his word and never invited Diddley back to his show.

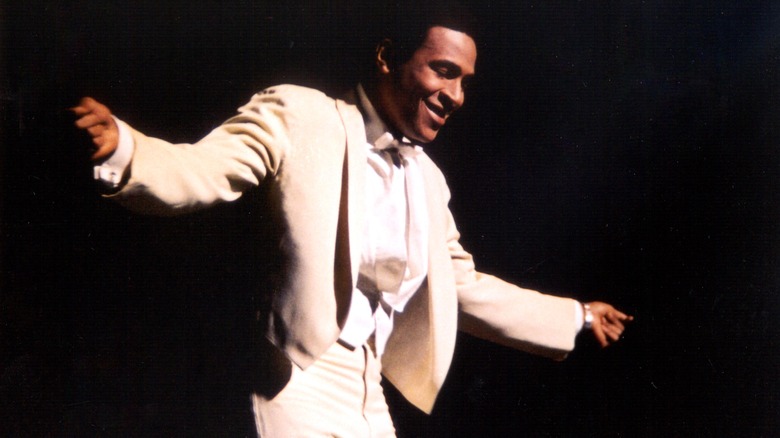

Bo Diddley helped Marvin Gaye get started

After his discharge from the U.S. Air Force in 1957, future soul and R&B legend Marvin Gaye returned to his home in Washington, D.C. and turned his attention to making it in the music business. Inspired by the Moonglows, the group best known for the 1954 hit "Sincerely," Gaye formed the vocal group the Marquees with his high school friend Reese Palmer and singers James Nolan and Chester Cardoza. As documented in Steve Turner's "Trouble Man: The Life and Death of Marvin Gaye," the Marquees struggled to garner attention in the D.C. music scene until a friend of a friend of Gaye's introduced them to Bo Diddley. Diddley, who moved to Washington, D.C. in 1959 and lived there through the mid-1960s, had a recording studio in the basement of his home just outside of Mount Rainier, Maryland, and agreed to work with Gaye's group.

With Diddley's help, the Marquees recorded their only single, a Western-themed novelty song titled "Wyatt Earp." Although the song flopped, and the Marquees would go their separate ways, it was nonetheless an early milestone in Gaye's groundbreaking singing career.

"I loved Bo," Gaye told David Ritz, author of "Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye." "Meeting him was a very important moment in my life. Bo was a rhythmic genius. Like James Brown, he was a certified witch doctor. He was also able to write out of his own experiences. His songs said exactly what he was thinking. I admired that."

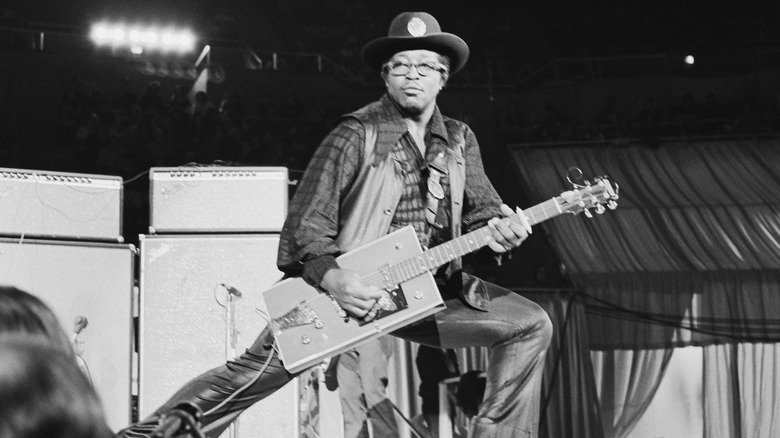

Bo Diddley designed and played some weird guitars

Long before ZZ Top adopted radically shaped instruments, Bo Diddley was designing, modifying, and playing his own quirky guitars. The most famous of Diddley's guitars is the Twang Machine, a home-built instrument that would become his trademark. In a 1997 Vintage Guitar feature, Diddley opened up about the origins of the famous rectangular guitar. "I made one when I was a teenager; its pickup was the part of a Victrola record player where the needle went in. I clamped it to the metal tailpiece to pick up the vibrations," Diddley recalled. "I wasn't able to buy electric guitars back then, so I built them, and they worked pretty good. Somebody stole the square guitar I built, but in 1958, Gretsch made me one with DeArmond pickups."

The final evolution of the Twang Machine, built by Australian guitar innovator Chris Kinman and dubbed the Mean Machine by Diddley, featured a variety of onboard effects and an equalizer. The Mean Machine would be one of Diddley's main guitars until his death.

Bo Diddley once opened for the Clash

In the late 1970s, the Clash was the biggest punk band in the U.K. Combining the rhythms of early rock, elements of reggae, and pure aggression, the Clash was cementing their hyped reputation as "the only band that matters." For their first American tour in 1979, they would need a knock-out of an opening act. As longtime fans of early rock 'n' roll, the Clash knew there was only one man for the job.

To most fans, Bo Diddley and punk rock probably seemed like a musical mismatch, but to the Clash frontman Joe Strummer, it made perfect sense. The Clash was intent on putting the spotlight on rock's originators and introducing them to a new generation of fans.

A star-struck Strummer was blown away by his hero. According to Kris Needs, author of the biography "Joe Strummer and the Legend of the Clash," Joe Strummer confessed, "I can't look at [Bo Diddley] without my mouth falling open."

Diddley, however, was less than impressed with the young English upstarts and their ear-splitting sound. In a late career interview, Diddley recalled opening for the punk legends. "That was ridiculous," Diddley said. "If you can play, you don't need 12 amplifiers stacked upside the wall ... My ears is hurting still from listening to that crap! But every generation's got its own little bag of tricks."

Deputy Bo Diddley

As detailed in a 2019 Valencia County News-Bulletin feature, Bo Diddley fell in love with New Mexico after shooting the film "Crush Proof" with actor Dennis Hopper in the state. A California earthquake convinced Diddley to take up residence in the town of Peralta in Valencia County, New Mexico, in 1971. Diddley, his wife Kay, and their children Terri, Tammy, and Anthony lived in Peralta for around seven years. Diddley loved the relaxed lifestyle in the small New Mexico community, telling the News-Bulletin, "Everything's just kind of groovy here, you know? Everybody's not running and ripping, knocking each other down."

Diddley tried his hand at ranching and owned 11 show and quarter horses, cows, chickens, ducks, and sheep, but music remained his passion. He built a recording studio constructed of adobe on his farm and lent his years of experience to help local musicians.

Hoping to make a difference in the community, Diddley joined the Valencia County Citizens' Patrol as a deputy and personally bought three squad cars for the sheriff's department. "He loved it," daughter Tammi told the News-Bulletin. "He loved playing sheriff, he loved the community ... He had a soft spot for law enforcement." As a volunteer deputy, Diddley enjoyed working with young people and educating kids about the dangers of drugs and alcohol. When asked about his stint in law enforcement, Diddley told The New York Times, "Well, somebody's got to do it."

Bo Diddley sued Nike

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, athlete Bo Jackson made history by playing both professional football and baseball. Eager to cash in on the celebrity of the only athlete to make the All-Star game in two sports, sports apparel company Nike launched a wildly popular ad campaign for its cross-training shoes with the sports star as spokesman. The ads featured Jackson successfully engaged in a variety of athletic activities punctuated with the phrase "Bo knows" and the name of the sport. At the end of the commercial, Jackson tries to play guitar with disastrous results, then Bo Diddley steps up to declare, "Bo, you don't know Diddley!" In addition to appearing in the ads, Diddley also wrote and performed the music featured in the campaign.

As detailed by People, Diddley's contract with the sportswear giant was to last just two years. In 2000, Diddley discovered Nike was manufacturing t-shirts featuring his likeness and the slogan, "You don't know Diddley." After Nike failed to respond to several cease-and-desist missives from the rock legend, Diddley filed suit against the company in Manhattan Federal Court.

In July 2000, Nike and Diddley amicably settled the legal dispute. Although the details of the settlement remain sealed, Diddley expressed his satisfaction with the deal in a press release stating, "I've always enjoyed my relationship with Nike and am pleased that we were able to put this matter behind us."

A stroke couldn't keep Bo Diddley down

Despite losing two toes to complications from diabetes and a long history of hypertension and back pain, Bo Diddley remained in relatively good health and high spirits in the last years of his life. Crediting his lifelong abstinence from drugs and alcohol as the key to his longevity, Diddley continued to perform well into his 70s.

On Sunday, May 13, 2007, Diddley played what would be his last concert at Harrah's Casino in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Following a typically energetic performance, Diddley began to exhibit signs of disorientation. Rushed to an Omaha, Nebraska, hospital with elevated blood pressure and glucose levels, the rock pioneer had a stroke that affected the left side of his brain (via Reuters). Within days of the stroke, Diddley was up and walking around although his speech and comprehension were seriously impaired. As reported by Rolling Stone, Diddley returned to his Florida home to recuperate but suffered a heart attack during a check-up the following August.

Although his failing health had forced him to retire from performing, in 2007, Diddley was well enough to attend a dedication of a marker celebrating his career on the Mississippi's Blues Trail in his hometown of McComb. Inspired by the performance of local blues musician Jesse Robinson at the ceremony, Diddley took to the stage one last time. Bo Diddley died of heart failure on June 2, 2008, as per the Chicago Tribune. He was 79.

Bo Diddley's posthumous PhD

For much of his life, Bo Diddley rarely got the credit he was due as a founding father of rock 'n' roll. An influence on artists as Bill Haley, Elvis, Buddy Holly, and countless others, Diddley was acutely aware of his place in history despite never achieving the level of fame as his contemporaries. ”I opened the door for a lot of people," Diddley told The New York Times, "and they just ran through and left me holding the knob ... Have I been recognized? No, no, no. Not like I should have been."

Near the end of his career, Diddley finally began seeing some long overdue accolades. In 1987, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. An induction into the Blues Hall of Fame would follow in 2003. In 1998, Diddley received a lifetime achievement Grammy.

In August 2008, Diddley, who had dropped out of high school to follow his musical dreams, was posthumously awarded an honorary doctorate in fine arts from the University of Florida. Accepting the honor on behalf of her father, Evelyn Kelley told the Gainesville Sun, "He's looking down, giving us a big hoo-ha!"