Secrets The Roller Coaster Industry Doesn't Want You To Know

Human beings are like the only animal on the planet that loves to be scared. We love horror movies, we love those dumb Halloween haunted houses with all the jump-scares, and we love roller coasters. Because internally, we know that horror movie villains can't kill us, that dude's chainsaw isn't real, and we're not going to get hurt on a roller coaster.

Now's the part where we tell you that all of your preconceived notions are incorrect. While it is true that the horror movie villain (probably) won't climb out of the screen and kill you, there have been one or two accounts of people with heart conditions dying during the most terrifying parts of horror films. And the same sort of thing has been known to occasionally happen in a Halloween haunted-house, too. But those incidents are pretty rare, compared to the accident statistics for roller coasters. So just how safe (or unsafe) are those wild rides that we'll happily spend hours standing in line for? They might not be telling us everything we need to know.

Yes, roller coasters can cause neurological damage

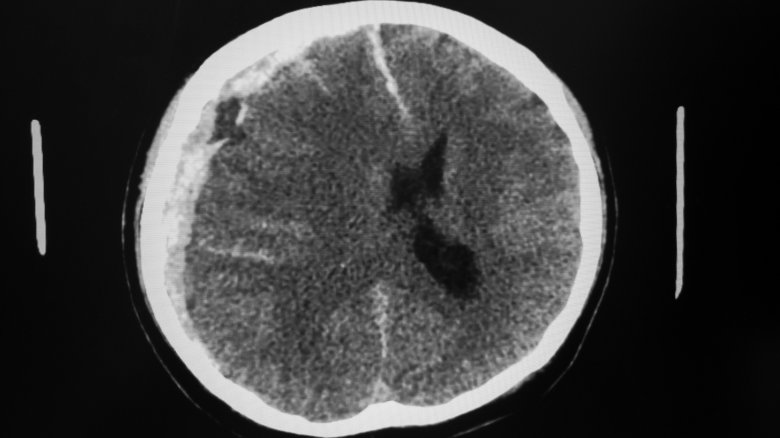

It's worth noting that roller coaster-related fatalities really aren't that common, but there have been reports of bizarre things happening inside the skulls of occasional riders. According to Science Direct, the most common neurological injuries suffered by roller coaster riders are subdural hematoma, which sounds vaguely unsettling, and cervical artery dissection, which what the hell, let's never get on another roller coaster again, ever.

The main thing to keep in mind is that roller coasters can exacerbate pre-existing conditions. In 2001, a woman died on the Goliath roller coaster at California's Six Flags Magic Mountain. According to the LA Times, the coroner concluded that she had a brain aneurysm, which is a bulging blood vessel, that she was likely unaware of when she got on the ride, and the stress of the ride itself helped the aneurysm rupture.

So in conclusion, don't ride roller coasters if you have a brain aneurysm, which by the way you may not know about unless you ride a roller coaster and your aneurysm kills you.

No, roller coasters aren't all well-regulated

Okay, so the whole brain aneurysm thing is kind of a wild card, but at least we know that federal regulations and safety rules will keep us from ever getting on a poorly maintained or inherently dangerous ride. Right?

Umm ... well. According to the Boston Globe, the entire amusement park industry is under-regulated. There's no federal oversight, and each state has its own set of thrill-ride safety laws. It's been that way since 1981, when Congress passed legislation removing the authority of the Consumer Product Safety Commission over fixed-site rides. So it's just those portable amusement rides — the ones that are hastily assembled at your local fairgrounds once a year — that are subject to federal regulation. That does make sense when you consider that those rides are a lot more likely to fall apart in a stiff breeze than something that's been designed to remain in the same spot for decades. But just because certain kinds of rides obviously need oversight doesn't necessarily mean that other rides need no oversight at all.

And this is all made worse by the fact that amusement parks aren't exactly given to transparency. So if you want to know how many people have died or been injured on the Colossus Exterminator Black Mamba Inferno before you get on the terrifying-looking thing, well, good luck with that.

And it's not like the states do an awesome job of it, either

Okay, so that means the states are picking up the slack, right? Well, according to the IAAPA, as of 2018, six states had no theme park ride regulation in place at all, at any level. A 2016 report by legal firm Motley Rice says many states lack comprehensive government oversight, and other states punt the responsibility to county governments and/or private inspectors. And six other states don't seem to be concerned about theme park safety at all. In some states, you have to look to private insurance companies to keep theme parks in line, and many of those companies only require annual safety inspections, which seems pretty lax for machinery that can run hundreds of times a day and is subject to the daily wear-and-tear of multiple G-forces.

A few states sort of regulate theme parks, but they let the parks hire their own inspectors and they limit their oversight to half-assed stuff like random paperwork audits. Other states, like New Jersey and Pennsylvania, have a small army of state inspectors whose full-time job is to do thorough inspections of popular thrill rides. Weirdly, Florida is pretty good about doing those safety inspections but they exempt any theme park that has 1,000 or more employees. So Disney World, Universal Studios, and SeaWorld get to do their own safety inspections, even though other parks in their state are subject to inspections by state-trained inspectors. So just in case you were thinking that the big parks are a safe bet, well, that depends on how much you trust Disney and on how you define "safe."

So this means mobile carnival rides are safer than they seem, right?

Safety at big, fixed-location theme parks really depends on state regulations, but maybe traveling carnivals are safe, since they're subject to federal oversight, right? You didn't actually read that sentence and think that might be true, did you? Because we've all experienced that unsettling feeling of looking at a wacky roller coaster and thinking to ourselves, "Crap, that thing looks like it's going to fly apart."

Unlike fixed-site roller coasters, the coasters and other rides at traveling carnivals are frequently disassembled and reassembled, which is scary if you spend too much time thinking about it. According to Thrillist, traveling carnivals are on the road 9-10 months of the year, and they might change locations weekly. But carnival operators will tell you that the assembly/disassembly process helps make the rides safer because it allows technicians to view every part of the ride and catch potential problems as they arise.

On the other hand, carnival workers are overworked and underpaid, and there is no routine inspection by federal investigators — they usually only step in after an accident has already happened, which isn't very helpful, frankly. So it doesn't seem to matter if you're at a carnival or an amusement park, no one can really guarantee your safety when you board that ride.

What about the vomit?

Exposure to someone else's vomit won't usually kill you, unless it's Ebola vomit. Ebola victims don't usually ride roller coasters, though, so barf isn't a fatal threat when you're at an amusement park. Still, ew. No one wants to touch someone else's barf. So how often does barf actually happen at amusement parks?

Well, unsurprisingly there's no federal or state oversight of amusement park barf, so no one can really answer that with any sort of accuracy. We can, however, give you an example from one of the nation's most popular theme parks. The Cedar Point amusement park in Sandusky, Ohio, boasts 17 different roller coasters, and the head of the park's ride operations department told the AV Club that rides get shut down maybe once a day because someone barfed. But don't worry because she also said that "ride operators are aware of how to deal with blood-borne pathogens because they go through a specific training."

So after the barfing incident, the ride gets shut down and cleaned with a disinfectant and "a product that absorbs." Then it has to be run for about 10 minutes with no one on board, and then after that people get to ride again, so yay. You get to play barf roulette, secure in the knowledge that maybe the seat you're sitting in isn't the one that was barfed on 10 minutes ago, even if it has certainly been barfed on at some point.

People with heart conditions should not ride

Most roller coasters have warning signs. You know the ones: "Guests with the following conditions are prohibited from riding: Recent surgery, heart trouble/high blood pressure, neck trouble, back trouble, or are pregnant, or any physical conditions that may be aggravated by this ride." Okay so no recent surgery, check. No back or neck trouble, check. Not pregnant, check. But heart trouble or high blood pressure — well, Pacific Medical Centers says that 3.7 million people in America have an undiagnosed heart condition, and one in three adults have high blood pressure, which means a lot of people aren't even aware of the danger. And according to Medical Express, even people who know they have heart conditions and have been warned against riding roller coasters totally ride anyway because safety precautions are for wimps. Anyway, it's not like theme parks require a complete annual physical and doctor's note for everyone who gets on the ride.

A 2005 study by the American Heart Association found that roller coasters can speed up the heart and that a faster heart rate can lead to arrhythmias (irregular heartbeat) in people with heart disease, which can put them "at risk of having a cardiovascular event." So if you know you have a heart condition, cool, just don't ride. If you don't know you have a heart condition, though, just close your eyes and pray. That's what most people do on roller coasters anyway.

Rest assured, that teenage ride operator has a full 2.5 hours of training

Well, at least you can be sure that the guy strapping your kid into that crazy-looking roller coaster has undergone rigorous training and is uniquely qualified to make sure everyone stays safe while onboard. Right? Ugh.

The head of Cedar Point's ride operations department told the AV Club that ride operators have to take an "International Ride Operator Certification" course before they're allowed to start working the individual rides. So that sounds awesome and super-reassuring, except the course, she later revealed, only lasts about two and a half hours. So the people who take your kid's life into their hands when they strap him or her into a machine that travels 80 mph only have to undergo about 1.25 percent as much training as, say, a barber working in New York state. But don't worry, they also have to spend some time training at the ride, and 8-10 hours being "shadowed" by an experienced ride operator before they are declared a-okay to run a giant, dangerous piece of machinery full of vulnerable children and undiagnosed heart patients. And it's not like people working low-paid jobs doing super-redundant things don't take their jobs seriously or anything. Happy riding!

G-forces are not necessarily harmless

Part of what makes thrill rides so appealing is that they subject us to forces we don't usually encounter while we're just walking around doing boring normal-person things, or even when we're breaking traffic laws on a long, straight freeway or winding mountain road. The Knott's Berry Farm website, for example, brags that their "Xcelerator" coaster will "Rocket [you] 0-82 mph in 2.3 seconds as you fly 205 feet into the air before immediately hurtling 90 degrees straight down." Whee! Let's go.

The Xcelerator isn't even the most extreme roller coaster, at least not as far as G-forces are concerned. As of 2016 the G-force record for a roller coaster was 6.3 Gs — just for comparison, astronauts only experience about 3 Gs during a rocket launch, although granted, those G-forces last a lot longer than they do on the typical roller coaster ride.

According to the New York Times, a 2002 study published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine compared some roller coaster-related injuries to shaken baby syndrome. These injuries, researchers said, could be "direct or indirect and usually involve acceleration, deceleration, or both." Later research seems to support those earlier conclusions — in 2016, a report in Retinal Cases and Brief Reports also compared acceleration-deceleration eye injury to shaken baby syndrome and noted that doctors should consider roller coasters as a potential culprit whenever these types of injuries don't have other explainable causes.

Amusement park attractions send a lot of people to the ER

In 2016, NBC says there were 30,900 emergency room visits for injuries "caused by amusement park attractions." In the industry's defense, though, it's not clear how many of those injuries happened on roller coasters vs., you know, choking on a funnel cake while riding the merry-go-round or something. So it might be more useful to just look at roller coaster deaths and then extrapolate from there just how dangerous thrill rides actually are.

Between 2010 and 2017, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission says there were 22 thrill ride fatalities. Not all of them, though, were people getting killed on rides — sometimes people get killed doing stupid things, like getting struck while trying to retrieve a lost item. And the industry points out that 335 million people visit amusement parks every year, so the fatality rate is really very low. Those numbers, though, don't say how many people are actually riding, compared to how many people are all, "I'll just sit this one out and make sure no one steals your purse, honey," so we don't really have any solid numbers.

Still, the International Association for Amusement Parks says your chances of sustaining a theme-park injury serious enough to get you an overnight hospital stay is about one in 16 million, which is way, way better than your 1 in 700,000 chance of being struck by lightning in any given year.

Surprise — theme parks might not be totally forthcoming about their accident statistics

That 30,900 ER visits statistic from 2016 came from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), which is probably relatively impartial when it comes to gathering and reporting data on theme park accidents. So it's really interesting to compare that number to the number of accidents the theme park industry says it has every year — according to CNN, the International Association for Amusement Parks (IAAP) conducts its own annual safety survey, which we're sure is super impartial and not at all influenced by the financial interests of its members. The IAAP reports that there were 1,253 "ride-related injuries" in 2016, compared to 1,508 in 2015 and 1,146 in 2014. Granted, the IAAP's report only tracked fixed-site amusement rides, while the CPSC numbers also include mobile carnival rides and other amusement park attractions. Still, the difference between the two statistics is 29,647, so either carnival rides are like 24 times more dangerous than fixed-site amusement rides and other attractions, or the IAAP is seriously under-reporting the number of injuries that happen at theme parks.

And let's not lose sight of the fact that not everyone seeks medical attention for an injury, and that theme park authorities almost certainly aren't made aware of every single accident that someone has on park grounds. So both of those statistics are likely to understate the total number of accidents that happen on roller coasters and other park attractions.

Wooden roller coasters require more maintenance than steel ones do

Those extreme, modern roller coasters with their twists and drops and G-forces might seem scary, but no roller coaster gives you quite the same sort of thrill as a 100-year-old wooden coaster, for one simple reason — high-tech roller coasters are high-tech, which provides at least the illusion of safety. A wooden roller coaster that was built 100 years ago is a wooden roller coaster that was built back in the days before seatbelt laws were a thing and when people used radioactive water to treat arthritis.

Not all wooden coasters are old, though. According to the New York Times, some parks are installing brand-new wooden roller coasters because wooden roller coasters have features you won't find in steel-rail designs. They're slower, so they can have tighter turns than steel roller coasters can. But they're also temperamental and require more maintenance. A badly designed wooden roller coaster might be slow and dull on a cold day and fast and potentially dangerous on a hot day. Wooden coasters will sag over time, too, and humidity can loosen the bolts, making the ride feel shaky and rickety.

It's all good, though, even a 100-year-old coaster is safe provided it's well-maintained — "It just takes more maintenance to make sure the wood and fasteners are in proper operating condition," Skyline Attractions President Jeff Pike told Mental Floss. And all theme parks, as we've learned, are well-regulated and can totally be trusted to make those judgment calls.

Waterslides are not just a wetter, safer version of a roller coaster

A waterslide is kind of like a roller coaster — it has the crazy turns, dips, and terrifying acceleration — so we're just going to throw this one in as a bonus.

You probably thought waterslides were the safer, watery version of a roller coaster. But a roller coaster is pretty much the same for everyone riding it, and on a roller coaster you're a passive participant: You just hang onto that safety bar and wait for it to end. Waterslides are not so simple. Because there are no seatbelts, waterslides are designed very specifically to keep everyone safe. But people are unpredictable, and they can break rules and do weird things and sometimes talk their way onto rides that they maybe shouldn't be on due to height or weight restrictions. Maybe that's why NJ.com found in 2014 that waterslides in that state were responsible for significantly more injuries than roller coasters. One person who became a quadriplegic after a waterslide injury contends that you may also need to have some level of physical competence — agility, control, and a certain amount of muscle — to actively participate in the experience of safely plummeting down that long twisty pipe into a shallow pool at the end. (He won quite a lot of money from the park where he was injured.)

So do you have the physical prowess to handle that waterslide? Or will you be safe going down it? Maybe! Probably! But make sure you fit any size restrictions for the ride, and try not to do anything too crazy on your way down. Remember, your main goal in amusement park rides is to stay live. Having fun comes second.