Did The Olympics Make Jesse Owens Rich?

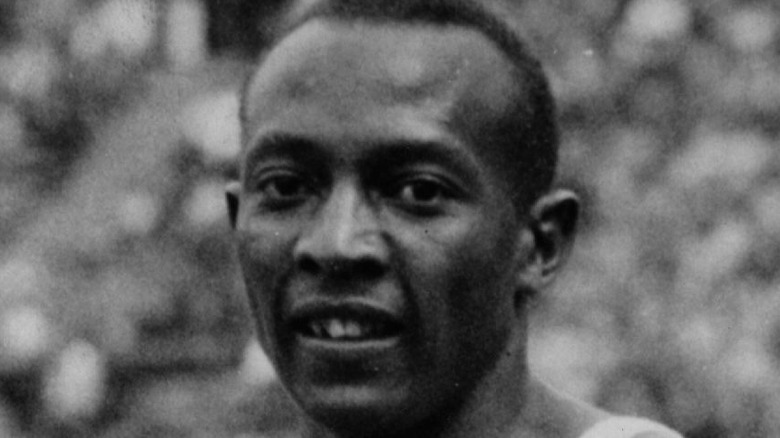

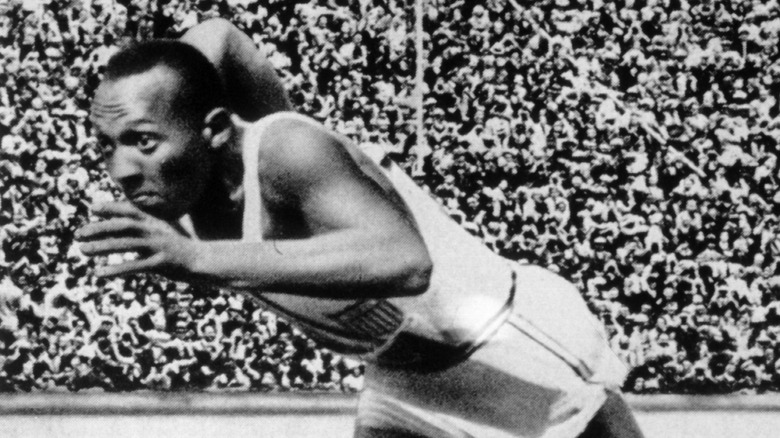

Out of all the pioneering African American athletes who made a name for themselves in their sport, track and field star Jesse Owens is arguably among the most iconic. Not only did he win four gold medals in the 1936 Berlin Olympics; he did all that in front of an audience that included Adolf Hitler, who made no secret about how he wanted the Olympics to showcase the white man's purported superiority in athletic competition, per Britannica. It's still unclear whether Hitler was so disgusted with Owens' success that he walked out of the stadium, but that lines up with the narrative that prevails up to this day — a Black man humiliated the Nazi dictator in the very country he ruled with an iron fist.

Had Owens achieved his impressive athletic feats in the present day, or even a few decades ago at the earliest, he would have almost certainly been besieged with endorsement offers and asked to appear on talk shows or make cameo appearances on television shows or movies. He'd likely be a mainstream celebrity like Usain Bolt, with his name well-known to casual fans, or even non-fans. But we have to remember that the 1930s were a very different time in history. Given the circumstances of his era, did Jesse Owens' Olympic success make him a rich man? To answer that, we'll first have to look back at what happened in the immediate aftermath of the Berlin Olympics.

Owens' struggles started when he was banned from amateur competition

On December 26, 1936, Jesse Owens defeated Julio McCaw in the 100-yard dash in Havana, registering an impressive time of 9.9 seconds. However, Julio McCaw was not a rising track and field prospect from Cuba, nor was he even human — he was a horse.

Just four months after making history in Berlin, Owens was competing in an exhibition race against a horse, and as he lamented years later (via The Guardian), the whole experience made him feel like a "freak." And it wasn't just horses he was racing against, but also dogs, cars, trains, and motorcycles. That's a strange — and degrading — way of treating an Olympic hero, and it was all because of a fateful decision from American Athletic Union and U.S. Olympic Committee head Avery Brundage.

While Owens was receiving big-money offers from the U.S., including one that would have had him appearing on early Hollywood star Eddie Cantor's radio show for $40,000, Brundage forced him to go on a post-Olympic tour to raise funds for the AAU and USOC. Despite being tired and broke, Owens had no choice but to visit several European countries and compete in various track and field events while dealing with substandard accommodations and, on one occasion, only eating his first meal of the day at 4 p.m. When Owens had enough and decided to go back home to America, Brundage swiftly responded by permanently banning him from all amateur athletic events.

He worked various jobs throughout the '30s and '40s and filed for bankruptcy in 1939

It's not clear how much Owens made while racing against animals and vehicles, but one thing is certain — he had a hard time making ends meet in the decade or so after the 1936 Berlin Olympics. According to The Guardian, he opened an eponymous dry cleaning business in his hometown of Cleveland, but by 1939, it had gone belly-up, with the Olympian filing for bankruptcy that same year. It was yet another example of how hard it was for Black people — even former Olympic heroes — to make a decent living in a largely segregated America.

In 1940, Owens found work as a salesman for the Lyons Tailoring Company, which hoped his popularity would lead to good business, but he was fired after just six weeks. The official website of the Olympics notes that Owens worked a few other menial jobs around that time, including gas station attendant and playground janitor.

According to Case Western Reserve University's Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Owens also worked as a professional entertainer in the late 1930s and was hired as the director of a national fitness program for African Americans during World War II. Similarly, he worked for Ford as an assistant personnel director for Black workers but was let go from this job when the war ended. Still based in Detroit after he lost his job with Ford, he opened a sporting goods store in the city, but that, too, didn't last long for the four-time gold medalist.

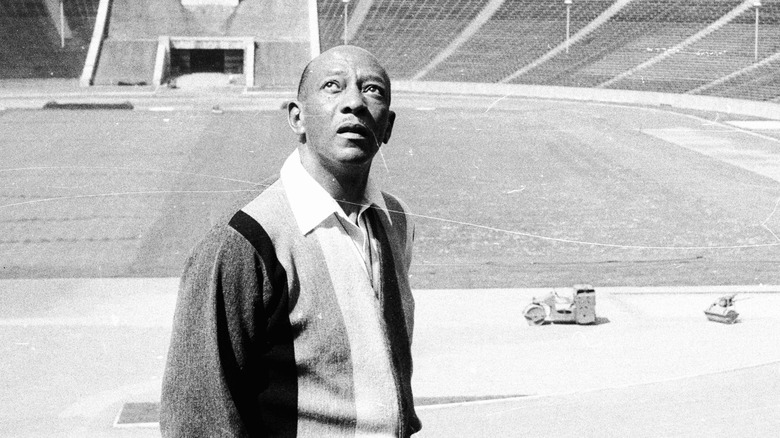

Owens' fortunes changed when he became a public speaker

After years of struggling to provide for his wife and children, Owens' fortunes began to change for the better in the 1950s, according to Olympics.com. He started a public relations firm and became an in-demand speaker who delivered speeches to major companies such as Ford, as well as the U.S. Olympic Committee — the same organization that previously slapped him with a lifetime ban from amateur competition. These speeches mostly focused on positive values such as patriotism, sportsmanship, and healthy living, and as Sports Illustrated's William Oscar Johnson wrote in 1972, he was an "all-round super combination of 19th-century spellbinder and 20th-century plastic P.R. man" whenever he was on stage as an orator.

Accounts vary on how much Owens made as a public speaker — per Johnson, he made "upwards of $75,000" for 80 to 90 speeches per year, while other reports claimed he earned as much as $100,000 annually for two to three weekly speeches. Either way, it was truly a long time coming for one of America's greatest sports icons ever, and while he was never the richest former athlete in the U.S. at the time, his public speaking engagements finally allowed him and his family to live comfortably.