Messed Up Things That Happened During The American Revolution

For many American students, the version of the American Revolution that's presented in school is pretty thoroughly sanitized and simplified. In some respects, that's necessary, as the colonial rebellion against Britain was actually pretty complicated and contained a dizzying array of different viewpoints, events, and political players. That's the stuff graduate theses are made out of, not middle school essays.

Yet, neither is it totally fair to present the American Revolution as a simple, two-dimensional battle between two sides. In fact, even a small amount of digging into the subject will show that the fraught, complex war had a pretty serious dark side. There's the standard horror of war, of course, but the war reached not only onto the battlefield, but into homes, rural communities, and even the then far-flung frontiers of colonial America. Practically everyone was affected.

Regardless of whether we're talking about British redcoats or rebellious colonial Patriots, both sides both witnessed and committed some pretty messed up things during the American Revolution.

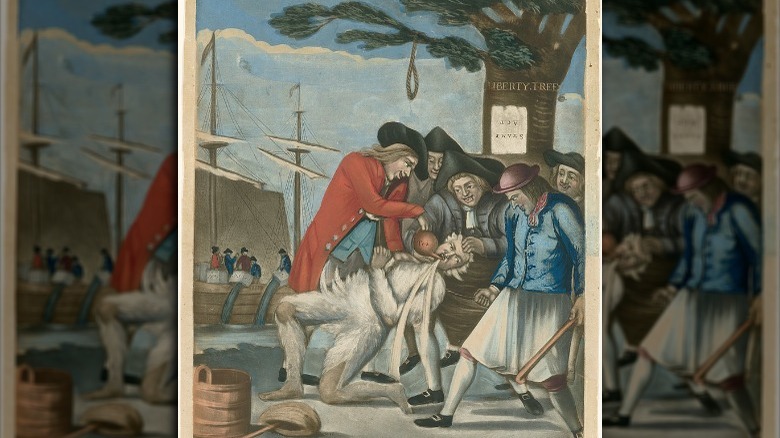

Tarring and feathering was a painful punishment

Since revolutionary days, tarring and feathering has become somewhat mythical. For many modern readers, the idea of coating someone in hot tar, followed by a layer of loose feathers, sounds both humiliating and utterly painful. But how messed up was it, really?

First, as the Journal of the American Revolution notes, there are no reports that tarring and feathering ever killed anyone. Yet, it could still be pretty brutal. Some people could suffer blisters from the hot tar, while an angry mob certainly wasn't above landing a few good kicks and blows during the process.

The main point of tarring and feathering was to inflict psychological suffering. A person who was subjected to the treatment was displayed for others to gawk and laugh at them. One man, a sailor named George Gailer, was tarred and feathered in 1769 for working with British customs. Afterwards, his captors reportedly took Gailer around Boston in a cart, parading him about and occasionally whipping him for three hours. Gailer clearly survived, given that he later sued a number of his attackers, but was also obviously upset over the humiliation of the incident.

Troops treated prisoners of war harshly

By the 18th century, many European powers were quick to acknowledge that certain prisoners of war had rights. They were to be treated decently well, at least as far as the generally accepted code of conduct went. In the American Revolution, however, captured colonists were understood to be traitors, according to Mount Vernon. This means that their treatment varied quite a bit, sometimes veering into brutal territory. One British general even ominously said that captured Patriots were "destined to the cord" — that is, that they would surely be hanged (via The New York Times).

The issue went both ways. While Americans captured by the British could face harsh, even squalid conditions that threatened their health, some Loyalists could experience much of the same. Or, at least they said they did. Per Mount Vernon, in the "Asgill Affair," captured British Captain Charles Asgill was ordered executed by George Washington after Loyalists had themselves hanged Continental Army Captain Jack Huddy. Asgill was never killed but, later, he alleged that his time as a prisoner was one of very poor treatment indeed. Washington vehemently denied the assertion.

Colonial troops also reportedly fired on British and Loyalist soldiers throughout the war. Per Slate, Patriot soldiers in South Carolina fired upon surrendered British troops, while a 1778 mob in Georgia killed another small group who wouldn't speak out against King George III.

One 1780 incident in South Carolina broke the rules of engagement

When a military figure in the American Revolution earns a nickname like "Bloody Ban," you know the origin story of that name has got to be pretty messed up. And for Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, it's been so notorious that his name became shorthand for brutality.

According to History, in May 1780, Tarleton was commanded to stamp out any remnants of rebellion in the colony of South Carolina. On May 29, near Waxhaws, Tarleton and his troops surrounded and defeated a group of Patriots under the command of Colonel Abraham Buford. The group, consisting of about 350 men, surrendered. After that surrender, however, British soldiers continued shooting, killing people who had already officially given up. Ultimately, 113 colonists were killed and 203 captured in the Battle of Waxhaws, compared to 19 British dead.

The event became emblematic of British brutality for the rest of the war, used by pro-Patriot sources to bolster their cause and further the perception of the British as bloodthirsty, heinous overlords. Most strikingly, it gave rise to the term "Tarleton's Quarter," a darkly ironic phrase that meant a victor would give no mercy at all but would instead vengefully kill everyone despite the rules of engagement.

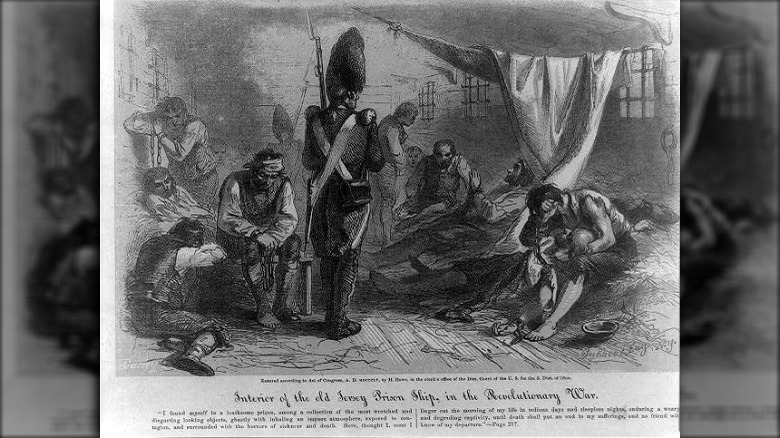

Prison ships were floating horrors of the American Revolution

If you were a rebellious colonial, undoubtedly you didn't want to be captured by the British and subject to a wide range of different conditions. Some prisoners of war could be treated pretty humanely, if they were lucky and perhaps of a higher profile than the rest. But the truly unlucky would be put in prisons so harsh that the barbarity of their conditions remains notorious more than two centuries after it all happened.

The worst of the worst, as history has it, were the prison ships anchored near Manhattan. According to Smithsonian Magazine, rebels were more likely to die aboard one of these floating prisons than they were on the field of battle. Specifically, as estimated 11,000 people died on prison ships alone during the American Revolution. Living conditions aboard the ships were, frankly, atrocious. Prisoners were packed belowdecks, leading to overheating, the spread of disease, and criminal neglect. Some aboard the ships reported that the dead would lie amongst the living for days and, when they were finally discovered by British soldiers, would simply be tossed overboard. Nearby people in Brooklyn would sometimes recover the remains on shore and give them a proper burial.

Food was especially heinous, it seems, with meals made up of rotten, moldy ingredients and foul water drawn directly from the East River. The HMS Jersey became especially notorious for its conditions, to the point where prisoners nicknamed it, simply, "Hell."

Colonists could get off the prison ships if they betrayed their cause

While conditions on British prison ships could be downright horrifying, some colonists trapped there were presented with a way out. However, for many, their release from the rancid conditions came with a pretty big price — turning their back on everything they'd been fighting for.

According to History, a pretty significant portion of captured enemy combatants were actually privateers. As the emerging United States didn't yet have its own navy, the Continental Congress instead gave the go-ahead to private vessels to capture and otherwise harass British ships. When the crews of these privately-owned ships were captured, they were sometimes given a choice between serving time on a prison ship (widely rumored to be hell on earth) or joining up with the British.

Tempting as the offer may have seemed, reports indicate that few people actually became turncoats, though it wasn't always for lack of coercion aboard the prison ships. Some British representatives offered cash incentives to prospective recruits. Some abusive officers were even said to let prisoners starve in an attempt to recruit them to the British side, according to the account of Ebenezer Fox, a prisoner on the HMS Jersey.

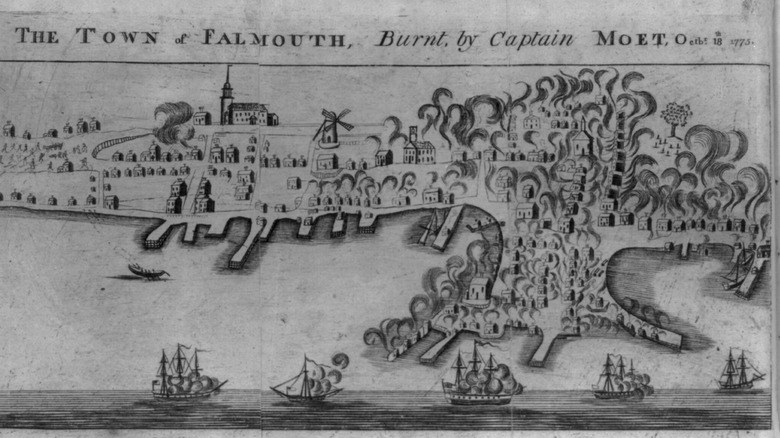

British warships destroyed American towns

If you were a supporter of the Patriot cause but weren't necessarily interested in fighting on a battlefield or joining up with the crew of a privateer's vessel, then you might choose the home front, so to speak. After all, what danger could there be in vocally supporting the cause from your own town, at least compared to what others were risking?

Turns out, you could risk quite a lot. Take the case of Falmouth, Massachusetts (now Portland, Maine). According to the Maine Public Broadcasting Network, this colonial stronghold was attacked by Royal Navy ships in 1775, which bombarded the town and destroyed over 400 buildings. To be fair, Lt. Henry Mowatt, commander of the squadron, gave the townspeople warning that he was about to attack, reading a formal notice that accused them of "unpardonable rebellion." The attack soon became a powerful symbol for the Patriot cause. And why Falmouth, and not one of the many other settlements along the coast that were deemed just as rebellious? The weather simply made it easier for the group of ships to make it to Falmouth.

A similar attack happened in Fairfield, Connecticut in 1779, according to Connecticut History. There, 97 homes and 48 businesses were burned. Residents were offered land in Ohio, then owned by Connecticut, which came to be colorfully known as the "Fire Lands."

George Washington was no friend to Iroquois people during the American Revolution

Though many of us now remember George Washington as a stern looking, white haired old man on the dollar bill or the cover of your American history textbook, the real George Washington was, of course, more complicated. And, for some people, he was no noble leader or founder of a new nation. He was a devourer of villages.

According to Mount Vernon, Washington was initially called "Conotocarious" by Tanacharison, a leader of the Seneca tribe, itself part of the larger Iroquois Confederacy. This nickname, which translates to "town taker" or "devourer of villages," was actually first granted to Washington's great-grandfather, John Washington, who was part of an attempt to suppress a Native rebellion that left five chiefs dead — after that had already agreed to negotiate.

While George himself didn't have anything to do with his great-grandfather's misdeeds, he arguably earned the Conotocarious name later in the American Revolution. According to The New York Times, during the war, Washington gave the go-ahead to General John Sullivan to take Continental soldiers and devastate Iroquois settlements after indigenous people sided with the British. Soldiers destroyed their crops, burned down structures, took prisoners, and violated graves. Washington himself was at the forefront of the plan, telling Sullivan to make sure he accomplished "the total destruction and devastation of their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible."

British surrender spelled trouble for enslaved people

Throughout the course of the war, quite a few enslaved people living in the colonies sided with the British. That's because, according to Smithsonian Magazine, the British were largely seen as potential liberators, to the point where one man even renamed himself "British Freedom." For Black Americans, the Patriots were more frequently enslavers who wanted to keep them in bondage for seemingly forever, to the point where they would fight a war over the matter.

The British were more amenable to freeing slaves, though they didn't outlaw slavery in most of their territories until 1833, according to Britannica. Still, for many enslaved people, it must have looked far better over on the British side. Who wouldn't become a Loyalist?

That was made all the more attractive when some British officials began promising freedom for slaves who fought for their side, as The Boston Globe reports. Quite a few left for the supposed enemy, including people ostensibly owned by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. After the war ended, they were faced with the undoubtedly depressing prospect of returning to their old lives. Both Washington and Jefferson took steps to reclaim their slaves in the aftermath of the revolution.

Valley Forge was brutal for Revolutionary soldiers - but so was everything else

Many sources will tell you that the winter of 1777-1778 was, for the Continental Army soldiers encamped at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, especially bad. Yet, according to the National Park Service, while the winter was tough, "it was not a time of exceptional misery in the context of the situation." That is, conditions at Valley Forge that winter were brutal, but then again, so were conditions for the Continental Army in many other places. Perhaps the most messed up thing about that season at Valley Forge was the fact that its hardships were just as bad as anything else a rebel soldier might experience.

During that winter, the soldiers were consistently hit with disease, most often contagious diseases that spread in unhygienic conditions, such as typhus, dysentery, and influenza. And then, there were the supplies. According to Mount Vernon, Washington and his officers were constantly negotiating for more supplies throughout the winter, to the point where soldiers and officers alike were sent out into the countryside to scavenge or practically beg for food.

Scalping became a horrifying tactic for soldiers on both sides

Though it's been traditionally associated with Native American attacks, the truth is that both colonists and British forces used scalping throughout the war to terrorize the other side. Or, at least, they used the threat of scalping. According to "Groundless: Rumors, Legends, and Hoaxes on the Early American Frontier," there are some accounts from soldiers on both sides that the enemy scalped deceased combatants. Some of the more horrific stories maintain that some soldiers were scalped while still alive, while others are vaguer about the type of mutilation that was said to have occurred.

There is a good chance, however, that scalping was more a horrifying rhetorical device and may not have happened nearly as often as those accounts suggest, as the Journal of the American Revolution reports. Whether or not it actually happened on the battlefield, the idea that the enemy (either the Patriots or the British, depending on who was telling the tale) scalped others was held up as an example of their brutality. Printers went wild with the accusations, printing pamphlets and newspapers purporting to carry true accounts of scalping, with some Patriot-friendly sources clearly using stories of scalp-hunting Loyalists as a way to bolster support for the rebellion.

Mobs could get dangerously violent

The stark political divides in colonial America were not only distressing from an interpersonal standpoint, but they could also grow deeply violent. Anti-Loyalist mobs menaced British sympathizers with social ostracization and physical violence, even killing some. Slate reports that Colonel Charles Lynch, a Virginia military man, was so notorious for his propensity to kill Loyalists that the term "lynching" supposedly comes from his actions.

Violence grew so bad that it pushed some Loyalists to flee the American colonies. "Liberty's Exiles" notes that many of these refugees left the rebellious colonies for other British territories, especially the northern colonies that would become part of Canada.

British soldiers' fears of mob violence grew to considerable proportions, to the point where it played a part in the Boston Massacre. The American Battlefield Trust notes that the bloody incident was precipitated by British troops arriving in 1768 Boston, a city already resistant to redcoats. By 1770, relations had grown even worse. When a young Boston man entered into an argument with a sentry in front of the Customs House, the altercation grew to involve a small group of British soldiers and a steadily growing mob of Bostonians. When someone hit a soldier, the British fired into the crowd, lending even more credence to the image of bloodthirsty British soldiers.

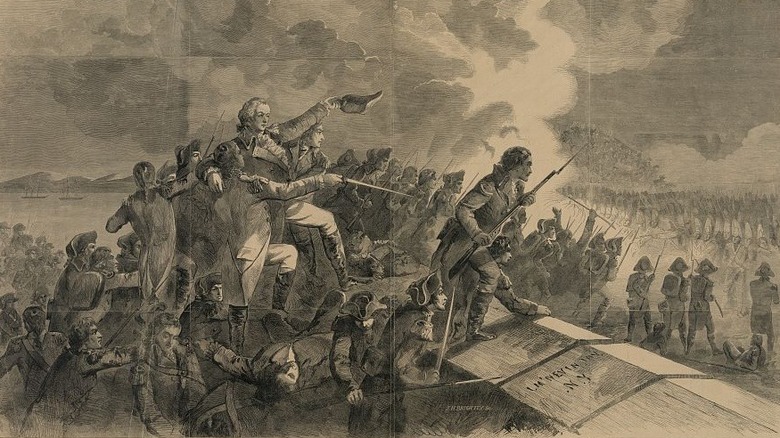

British soldiers killed sleeping troops in the Paoli Massacre

A secret attack is not necessarily a standout horror of war, though it's bound to be violent and potentially bloody nonetheless. Yet, one secret attack of the American Revolution proved to be yet more fodder for the perceived brutality of British soldiers.

It all happened near Paoli, Pennsylvania, according to History. There, on September 20, 1777, 5,000 British soldiers commanded by General Charles Grey descended upon colonial troops encamped there. To maintain the element of surprise, the British declined to use their loud muskets and instead planned to rely on hand-to-hand weapons like their bayonets. The Americans, meanwhile, were sleeping.

Per the American Battlefield Trust, the colonials, commanded by General "Mad" Anthony Wayne, lost 272 men, who were either killed outright or taken as prisoners of war. Later accounts by Americans alleged that some British soldiers had killed people who had already surrendered. The "Paoli Massacre," as it came to be known, was eventually made another emblem of British outrages against Patriots. And, as History notes, Wayne's later charge against Stony Point, New York recalled some of the worst elements of the attack at Paoli — Wayne's Continental soldiers also attacked at night, using only their bayonets to kill 94 enemy soldiers and capture 472 more.

Civilians weren't spared the horrors of the American Revolution

Even the most scrupulously neutral and mundane people living in the colonies at the time of the American Revolution simply could not escape the war. Even if they refused to participate in battles, mob violence, or any other of the myriad ways in which people engaged with the conflict, it still could come to their very front door.

According to the Journal of the Historical Society, the everyday impact of the war was widespread, with military action happening from Georgia all the way to the northern reaches of New England. Both British and Continental armies moved broadly throughout that vast region, passing through settlements as densely occupied as cities and as remote as lonely single-family farms. Colonial Americans were also often confronted by the violence of nearby battles and war-induced food shortages, which put considerable pressures on even the simplest day-to-day lives.

The movement of demanding and hungry troops through the land could be especially devastating. Soldiers often took whatever they wanted, sometimes with a semi-formal requisition, sometimes not. Crops, farm animals, and even wood from buildings and fences could be fair game. So, too, could be the bodies of vulnerable family members like wives and daughters, as the rumors maintained. It got so bad that some families chose to abandon their homes and become refugees as troops approached.