The Untold Truth Of Queen Elizabeth II's Coronation

Although British monarchs don't really believe in their divine right to rule (meaning they were appointed by God) anymore, they still have a fancy ceremony to officially assign that power to them. This fancy ceremony is called a coronation, and in 1953, it was Elizabeth II's turn to have hers. She'd already been queen for over a year by that point (more on that later), but that's how long it takes to plan something that brings together leaders and heads of state from all around the world, plus an impressive collection of family jewels.

By then, it wasn't just the royal family that was excited for an excuse to break out their poshest ballgowns and have a party. Britain had been demoralized by the violence and deprivations of World War II, and by its steady loss of power around the world. It needed a chance to let its collective hair down. So while the queen was adding just the right level of symbolism to her dress, the Duke of Edinburgh and the BBC were battling with the Archbishop of Canterbury, and a florist was inventing a still-beloved dish, people around the country were organizing street parties, and sweet-talking their slightly richer neighbors into letting them watch the whole shindig on a newfangled contraption called a TV.

From the crowns (multiple) to the robes (also multiple) to the procession route and the queen of Tonga who turned a downpour into her moment in the sun, this is the untold truth of Queen Elizabeth II's coronation.

Elizabeth II had to wait for her coronation

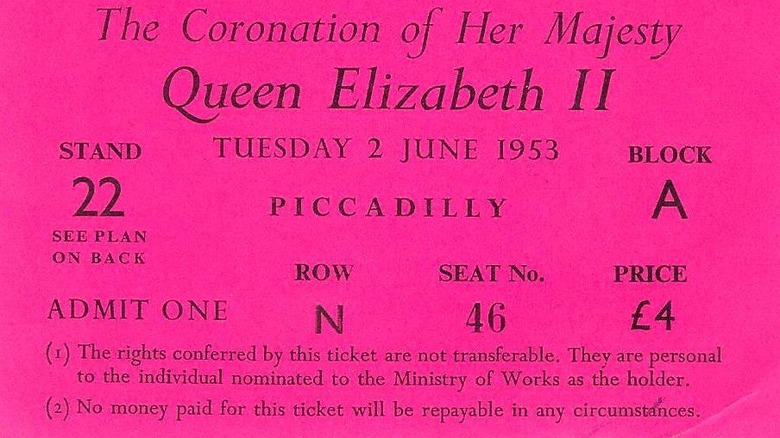

Elizabeth II's father and predecessor, George VI, died in his sleep at the family estate Sandringham on February 6, 1952. BBC History Extra reports that the cause was later found to be a blood clot. Elizabeth was in Kenya on official heir-to-the-throne business. As was custom, she and the rest of the British royal family went into a three-month period of mourning. In June 1952, preparations for her coronation got underway, with the first meeting of the coronation committee (chaired by the Duke of Edinburgh) meeting on June 16. The date of the coronation was set for just under a year later, on June 2, 1953.

This meant that Elizabeth was officially queen for 16 months before her coronation. The official mourning period ended in the summer of 1952, and she started performing her new queenly duties. In contrast, George VI only waited six months (from December 1936 to May 1937) between accessing the throne and his coronation.

Some have blamed Prime Minister Winston Churchill for postponing Elizabeth II's coronation, but historically, George VI was the exception. Queen Victoria, Edward VII, and George V all waited at least a year between becoming the monarch and their coronation. The reason George VI didn't have to wait that long was because coronation plans were already underway for his brother, Edward VIII, who abdicated for the twice-divorced American Wallis Simpson, leaving his shy younger brother to step into the role.

The organizer was not chosen based on merit

The British royal family typically prioritizes accident of birth over proven skill — it's how they got their own status, after all. So it's not super surprising that the person nominally in charge of organizing the Coronation got the job not through a rigorous interview process, but because of an archaic tradition.

According to the royal family's official website (yes, they have an official website), the task of organizing a coronation belongs to the Earl Marshal. That's a position, not a person. Since 1386, the Earl Marshal has been whoever happens to be the Duke of Norfolk. By 1952, Britain was on its 16th Duke of Norfolk: Bernard Marmaduke Fitzalan‐Howard. With a name like that, you'd definitely trust him to know how to pull off a huge royal ceremony.

To be fair to the duke, he had already overseen several major royal events. By Elizabeth II's coronation, he'd organized the coronation of George VI, and the funerals of George V and George VI. He would later arrange the state funeral of Winston Churchill (in 1965) and Charles' investiture as the Prince of Wales (in 1969). However, the Duke of Norfolk ultimately found himself reporting to another person filling a role he was also born into. Fitzalan‐Howard chaired the executive and joint coronation committees, which served under the coronation commission, headed by the Duke of Edinburgh, the queen's husband.

Britain really needed something to look forward to

By 1953, the people of Britain who didn't spend their time wandering around palaces and cutting ribbons really needed something happy to look forward to. It had only been eight years since the end of World War II. Luckily, Britain had come out of the war in better shape than the Axis powers and countries that had been occupied by the Nazis, and later by the USSR. Even in terms of casualties, Britain lost comparatively few people: 450,700 military members and civilians (excluding Empire troops), compared to, say, Japan, which lost as many as 3.6 million people. However, that still meant many families lost loved ones, many of those who did return were traumatized, and six years of war had torn other families apart. Several major cities were badly damaged.

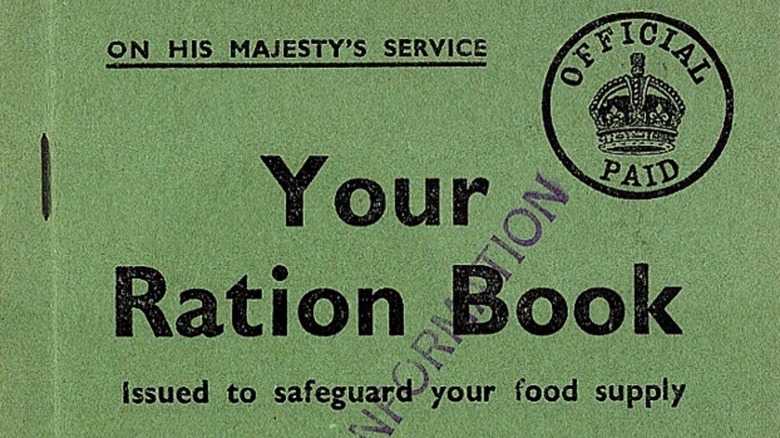

On the economic front, the war had bankrupted Britain, and once it was over, the country could no longer receive regular funding from America. Exports had been badly affected, and industries like railways and coal were under-resourced. Britain couldn't afford to import food, which meant that food products and other necessities that had been rationed since 1940 would continue to be so until as late as 1954.

In addition, as the Guardian explains, the British Empire was crumbling, as the government could no longer afford to resist calls for independence. Once a source of (misplaced) pride, this loss seemed to signal that Britain was losing its status as a world power.

The battle to televise Elizabeth II's coronation

By 1953, Britain had been crowning monarchs for nearly 900 years, yet no one who didn't have a written invitation had ever witnessed a coronation. For George VI's coronation in 1937, only a small segment of the return procession from Westminster Abbey to Buckingham Palace had been broadcast on TV by the BBC. But by 1953, the network had more experience filming large events, including Elizabeth II and Prince Philip's wedding in 1947. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the Archbishop of Canterbury Geoffrey Fisher, the Palace, and nominal organizer the Duke of Norfolk all opposed televising the coronation. They argued that the cameras would be intrusive, and that it would cheapen the solemn occasion.

However, the BBC's Director of Television, George Barnes, countered their concerns by pointing out that the cameras were barely noticeable, and that there was great public demand. He was right: Newspapers and members of the public flooded MPs with complaints. The MPs complained to Churchill, who ultimately came over to the TV side. As was his way, he dragged everyone else with him.

The broadcast became a pinnacle moment in the history of British TV. At that point, only two million people had paid for a TV license, but it's estimated that 20 million watched the broadcast. Friends, family, and even whole streets crowded around a single set for the chance to see the crowning of a queen. According to the CBC, 277 million people watched worldwide.

The weather was bad, even by British standards

Britain is a famously rainy nation: unverified legend has it that Brits are made up of 70% rainwater. The committee tasked with planning the Coronation did consider the possibility the queen would get soaked. They selected June 2 for the big day because meteorologists had estimated that it would be the least likely day of the year to experience rain.

How wrong they were. Although the morning was sunny, by the time the queen and her VIPs emerged from Westminster Abbey, it had turned into "the wettest June day in living memory," according to John Farren, who made a documentary about the Coronation for the BBC.

This wasn't such a problem for the queen and the attending dignitaries, who rode in closed carriages from doorstep to doorstep. But it somewhat dampened the atmosphere for the thousands of onlookers. Fortunately, as previously mentioned, Brits are attuned to wet weather. And one monarch braved the downpour to reward their patience. Queen Salote of Tonga won over the soaking crowds when she refused to raise the roof on her carriage — the only participant not to do so — which she was sharing with the Sultan of Kelantan. At the time of the coronation, Queen Salote was the only other female monarch in the Commonwealth. She was a regal, charming person: she was 6 foot 3 inches, and rarely seen not smiling. Her gesture so touched the British public that racehorses, songs, and babies were named in her honor.

The guest list was impressive

The best way to assert yourself as the one monarch to rule them all is to make sure a bunch of other monarchs and heads of state attend your coronation, where they can observe your power (and jewels) for themselves. The guest list for Elizabeth II's coronation was full of foreign and domestic royalty, and important political figures. According to the official Palace website, 8,251 guests squeezed into Westminster Abbey. Attendees included the heads of the Commonwealth states and various prime ministers, including Britain's then-prime minister Winston Churchill, who was said to have received the only cheer equal to the one the crowd gave for the queen.

These distinguished guests also rode in the processions from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Abbey and back. So did the Queen Mother and the princes and princesses of the blood: children of monarchs and grandchildren of royal male lineages. Notably absent, however, was the controversial Duke of Windsor, the former Edward VIII, and his wife Wallis Simpson. Elizabeth also had her own entourage, in the form of the Duke of Edinburgh and six maids of honor, chosen from high-ranking families by the Earl Marshal/Duke of Norfolk.

One of the least-famous guests present would later be the center of attention herself. Jacqueline Bouvier covered the wedding for the Washington Times-Herald, and married then-Senator John F. Kennedy just three months later. In 1961, the First Couple met the queen one-on-one when they visited Buckingham Palace for a formal dinner.

Regular people invited themselves

Another good way to exert your status as a monarch is to have loyal subjects line the streets, cheering for you. This was also a strong feature of the 1953 coronation. People who had no chance of getting an invitation to Westminster Abbey turned up a day early and camped out along the procession route, for the chance to glimpse the queen as she passed. According to BBC History Extra, some waited up to 20 hours for this moment. And let's not forget that it rained prodigiously that night, and on and off the next day. It's estimated that as many as three million people showed up to stand in the soggy London streets and cheer the procession on.

Some were there for business rather than pleasure. Military personnel lined the streets, and some marched in the procession. Of the approximately 30,000 service members who took part in the Coronation, 3,600 were from the Royal Navy, 16,100 were from the Army, and 7,000 were from the RAF, while the Commonwealth collectively sent 2,000, and 500 came from the Colonies.

The rain didn't ruin the atmosphere. Joan Matthews, who watched the Coronation from St. James' Street, near Buckingham Palace, recalled that the miserable weather inspired the crowd to cheer for anything they could, including "The men sweeping the road... a dog wandering down the road... one or two men who must have been lords or something."

Another big British triumph hit the headlines that day

If there's one thing the British have historically loved more than watching their tax money being spent on inducting a non-elected official to rule over them, it's conquering other lands. So June 2, 1953, proved to be doubly triumphant for the nation. On May 29, a British-sponsored expedition made up of Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa from Nepal, and New Zealand explorer Edmund Hillary became the first team to officially reach the peak of Mount Everest. Since Mount Everest is pretty remote and the people of the 1950s hadn't had the good sense to invent the internet yet, it took a few days for the news to spread around the world. Elizabeth II heard about it before the rest of the country: she was told the night before the Coronation, but newspapers broke it the following morning, on June 2.

Norgay and Hillary missed the Coronation, but they both met the queen. Later in 1953, Elizabeth II awarded Norgay the George medal, and knighted Hillary and expedition coordinator John Hunt. After Norgay's death, his grandson complained about the unequal treatment shown to Norgay compared to Hillary, the Guardian reports.

Elizabeth met Norgay again in 1961 at Rashtrapati Bhavan, the official home of the President of India, where he presented her with his book about the Everest expedition. According to the Evening Standard, Hillary and Elizabeth met "many times" until his death in 2012, aged 88: she sent a personal message of sympathy to his family.

The Coronation was broken into six stages

The Coronation started when Elizabeth II and Prince Philip left Buckingham Palace for Westminster Abbey at 10:26am, drawn in the Gold State Coach by eight grey horses. (And if you were wondering, they were named Cunningham, Tovey, Noah, Tedder, Eisenhower, Snow White, Tipperary, and McCreery: you're welcome, horse fans.) They arrived at the Royal Entrance at 11am, where they were met by various archbishops and Officers of State, and at 11:15, the procession into the Abbey began. The ceremony lasted nearly three hours, and was separated into six stages: the recognition, the oath, the anointing, the investiture (including the actual crowning), the enthronement, and the homage.

The anointing was considered too sacred to be broadcast over the heathen's medium of television, so this part was performed under a golden canopy held by four Knights of the Garter, the BBC reports. But we know it involved removing the Robe of State and George IV's Diadem, and the Archbishop drawing a cross on the queen's palms, chest, and forehead using a blend of orange, roses, cinnamon, musk, and ambergris, poured from a solid gold jug shaped like an eagle. All in a day's work for a royal. The anointment signaled that the queen had been blessed to rule by the God of the Church of England.

After that came the investiture, when the queen was presented with various symbols of monarchy, including the famous orb and sceptres, and was finally officially crowned with St. Edward's Crown.

Of course there were multiple robes

Elizabeth II's wardrobe for her Coronation was Highest-Level Posh, with a side of Symbolism. She started with a beautiful white dress, designed by British designer Norman Hartnell, who joined the project in October 1952. The final version had short sleeves, a sweetheart neckline, and a full skirt. Elizabeth also asked for embroidered images symbolizing the four countries in the United Kingdom. Which is why, the New York Times reports, the dress is embroidered in pearls, diamantes, and gold bugle beads in patterns shaped like Welsh leeks, the English Tudor rose, Scottish thistles, and the shamrock of Northern Ireland. Hartnell disliked the leeks, but the queen was a fan of the end result: she wore the dress a further six times.

Throughout the day, the queen added multiple robes over the dress. She entered Westminster Abbey wearing the crimson velvet-and-ermine Robe of State, aka the Parliament Robe, which she wears during the State Opening of Parliament every year. During the Anointing, she removed the robe and crown and added a plain white dress over her dress. For the Investiture, she put on the gold, coat-like Supertunica (aka the Robe Royal); the gold, scarf-like Stole Royal; and the gold, cloak-like Imperial Mantle. At the end of the ceremony, these were removed, and the robe she wore out of the Abbey was the Robe of Estate: a purple, velvet, satin-lined, ermine-edged robe, which took 12 embroiderers 3,500 hours to embroider with wheat ears and olive branches.

There were multiple crowns

Only having one crown is for rookies. Elizabeth II wore a grand total of three at her coronation. She traveled to Westminster Abbey wearing the George IV State Diadem. Made for its namesake's coronation in 1820, the frame is gold-lined silver with a pearl border, encrusted with 1,333 diamonds, set into four crosses and four bouquets of a Scottish thistle, Irish shamrock, English rose, and Welsh daffodil.

The diadem was removed during the anointing portion of the ceremony. Elizabeth was officially crowned with St. Edward's Crown, which is only used for coronations, starting with Charles II's in 1661. According to the Royal Collection Trust, St. Edward's Crown is made of solid gold, encrusted with 440 precious gems, including rubies, sapphires, and amethysts. Previously these were rented, but were permanently set in 1911, for the coronation of George V. Heavy indeed is the head that wears this crown: it weighs five pounds.

After the ceremony ended, Elizabeth II exchanged St. Edward's Crown for the Imperial State Crown, which was made for her father George VI's coronation in 1937, and which she still wears to open Parliament every year. This crown's most famous features are its legendary precious stones, including St Edward's Sapphire, Queen Elizabeth I's Earrings, the Black Prince's Ruby, and the Cullinan II (cut from the Cullinan Diamond.) In a rare interview, Elizabeth II recalled that it was "unwieldy." She added, "There are some disadvantages to crowns, but otherwise, they're quite important things."

The role of the Duke of Edinburgh

When Elizabeth II became Queen, her husband, Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, did not become king. The only men who can become kings of England are those who inherit the position in their own right. Philip had actually given up royal titles in order to marry Elizabeth (on November 20, 1947.) He had been Prince of Greece and Denmark, but he renounced these foreign titles, joined the Church of England, and was appointed Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Merioneth, and Baron Greenwich: as is tradition, he was known only by the highest title. On Coronation Day, Philip wasn't a prince: it wasn't until 1957 that he became Elizabeth II's Prince Consort.

But Philip was still involved in the Coronation arrangements. He was head of the coronation commission, and as the Guardian reports, he was one of the main proponents of televising the ceremony, opposing the older members.

On the day, Philip accompanied Elizabeth II in the Gold State Coach, wearing his Full Dress Naval uniform. Before the death of George VI made Elizabeth the monarch, he had served in the Royal Navy, retiring as a commander when it became clear that she would inherit the throne sooner than expected. In Westminster Abbey, the Duke wore a specially made silk and ermine robe, from the same company that made the queen's, and a coronet. During the homage, the Duke was the first non-Church official to kneel before the newly crowned queen.

The Coronation was crammed with symbolism

Since the British royal family's purpose is largely symbolic, the Coronation itself had to be stuffed with symbolism. Every shiny thing involved in the investiture part of the ceremony carried symbolic meaning. From the embroidery on the queen's dress to the flowers she carried, everything had a deeper meaning. For example, the queen carried a bouquet of white flowers that each represented the four kingdoms of the UK. The orchids from England and Wales also reflected the orchids she had carried on her wedding day.

During the investiture, before being crowned, the queen was presented with a series of objects that represent the "knightly virtues" that the monarch is expected to exhibit: chivalry, wisdom, courage, rewarding good, and punishing evil. These include golden spurs, golden bracelets (armills), and the Sword of Offering (as opposed to dueling.) Kings get to wear the sword, but queens don't. The other important one is the Orb, a jewel-studded gold globe topped with a cross to represent the Church of England ruling the world.

After being presented to the queen, all of these objects were offered to the altar. Just before the crowning, the coronation ring was placed on her right ring finger, and she was handed the Sceptre with Cross, and the Rod, which symbolize the monarch's control over their people, like a shepherd and their flock, according to Historic Royal Palaces, the organization that looks after these objects when they aren't in use.

There were parties across Britain

The queen returned to Buckingham Palace via a convoluted route that allowed for more waving. There, still wearing her Imperial State Crown and Robes of Estate, she and her family stood on the palace balcony for more waving to the cameras and onlookers below. After that, she hosted what was by then a very late "luncheon" (lunch is for commoners), which introduced a new dish that is still eaten today. Named Coronation Chicken, the royal family's official website reports that it was invented by Constance Spry, a legendary florist who had provided the flowers and apparently also knew a thing or two about cooking. It contains cold chicken, rice, green peas, and mixed herbs, covered in curry cream sauce and served cold.

The family came back to the balcony at 9:45pm, to oversee the turning on of specially arranged lights spread out across London. Meanwhile, people across Britain were celebrating with their own parties. Whole streets were closed off, decorated with bunting and packed with picnic tables, with everyone bringing sandwiches and cakes to share. Picture "The Great British Bake-Off" but in the 1950s. After years of austerity and uncertainty, it was a moment of national pride. People who were there remember dressing up in historical costumes, children doing pageants and recreations, and, as one man put it, "lots of alcohol being drunk." Well, it's not every day you crown a queen.