The Untold Truth Of Muddy Waters

Born in the fields of the deep South, the blues is a uniquely American art form. Embodying the struggles of Black Americans in the early 20th century, the blues has evolved from a music of the oppressed to a genre enjoyed across lines of race, wealth, and nationality. In less than a century, blues music traveled from the rural juke joints of the Mississippi Delta all the way to White House. At a 2012 celebration of the blues titled "In Performance in the White House: Red, White, and Blues," President Barack Obama summed up the importance and continuing appeal of this most American of musical genres. "[T]his music continues to speak to something universal," Obama said. "No one goes through life without joy and pain, triumph and sorrow. The blues gets all of that, sometimes with just one lyric or just one note."

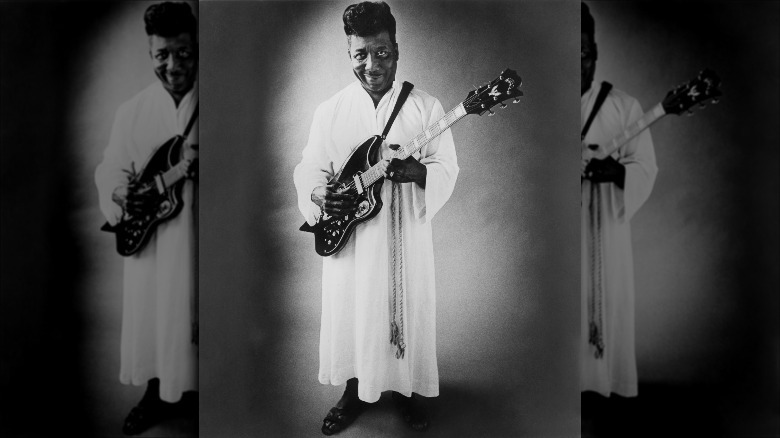

Few musicians loom as large in the history and development of the blues as McKinley Morganfield. Better known by his stage name, Muddy Waters, Morganfield left the cotton fields of Mississippi in the 1940s for better opportunities in the North. Bringing the country blues of the Delta with him, Waters made a practical decision that would revolutionize music. By setting his acoustic instrument aside and embracing the potential of the amplified electric guitar, the bluesman would help develop a sophisticated, urban-oriented form of blues music that would lead directly to the development of rock 'n' roll in the 1950s. This is the true story of Muddy Waters, father of the Chicago Blues.

The mysteries of Muddy Waters' birth

As documented in Robert Gordon's "Can't Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters," Muddy Waters' early years are shrouded in mystery — much of it self-created. Waters was sketchy on details in interviews, citing the year of his birth as 1915. He also told people that he was born in Rolling Fork in Sharkey County, Mississippi.

In truth, Muddy Waters was born McKinley Morganfield on April 4, 1913, in Issaquena County, northwest of Rolling Fork in a tiny community called Jug's Corner. Although Rolling Fork was and remains a small town – the population, according to the 2010 census, was just over 2,000 — it was, nonetheless, a metropolis compared to a rural bend in the road like Jug's Corner.

Waters' father was Ollie Morganfield, an amiable, burly man who made his living as a muleskinner hauling timber across the state to the sawmill in Vicksburg. Morganfield was also a talented musician known for livening Saturday fish fries by singing and playing the guitar. He was 21, a father, and recently separated from his wife when he met Muddy Waters' mother, Berta Grant, in the summer of 1912. Although the couple did not marry, their only son would be given his father's surname.

According to Gordon, virtually nothing is known of Berta Grant. No records of either her birth or death exist, and she died shortly after giving birth to McKinley. The circumstances of her death are unknown. McKinley Morganfield would grow up in the care of his grandmother, 32-year-old Della Grant.

Muddy Waters was raised by his struggling grandmother

Della Grant struggled raising her son and grandson on Cottonwood Plantation. Life as a sharecropper on a plantation in the early 20th century was barely a step above slavery. In exchange for a small plot of land and meager living quarters, a sharecropper was expected to work in the cotton fields from sunup to sundown. The landowner took half of the sharecropper's harvest and deducted his expenses for seed, tools, and livestock from what was left. Plantations functioned as privately owned towns, often with their own money good only at the farm owner's store. Ultimately, the conditions on a plantation were contingent on the character of the owner. Some were good. Some were bad. None were particularly fair. It was an especially hard life for a single woman raising two young boys.

According to biographer Robert Gordon, Della Grant had packed up her boys and moved 80 miles north to Stovall Plantation near Clarksdale, Mississippi, by 1920. Stovall's owner, Colonel Howard Stovall III, had a reputation for benevolence and generosity. Nevertheless, life remained hard for Della Grant.

Little McKinley Morganfield's love of splashing in the murky and often dangerous waters around his grandmother's home earned him the childhood nickname "Muddy." Stomping around in the dirty Delta water was one of the few pleasures for a child growing up on a plantation. Able-bodied children were required to work. After just three years of formal schooling, Muddy was forced to quit and go to work in the fields to help support his family.

A neighbor turned young Muddy Waters on to the blues

In an interview Link Wyler and Russ Ragsdale quoted by author Robert Gordon in "Can't Be Satisfied," Muddy Waters recalled his childhood on Stovall Plantation. "I started early on, burning corn stumps, carrying water to the people that was working," Waters said. "Oh I started out young. They handed me a cotton sack when I was about eight years old. Give me a little small one, tell me to fill it up. Really that never was my speed, I never did like the farm but I was out there with my grandmother, didn't want to get away from around her too far."

Although work dominated Waters' life on Stovall Plantation, he discovered the joy of music at an early age. Della Grant made sure young Muddy attended church every Sunday. Worship was a refuge for Stovall's sharecroppers, and services were lively and filled with song. In the pews of Stovall's church, Waters discovered the power of rhythm and melody.

However, it was music with distinctly different intent that really fired Muddy Waters' soul. "The lady that lived across the field from us had a phonograph when I was a little bitty boy," Waters told Robert Palmer, author of "Deep Blues." "She used to let us go over there all the time, and I played it night and day." Exposed to the recordings of such blues artists as Blind Lemon Jefferson, Tampa Red, and Memphis Minnie, Waters would develop a musical vocabulary and sophistication beyond that of other rural musicians.

Young Muddy Waters made music any way he could

As detailed by biographer Robert Gordon, music, often played on a variety of makeshift and manufactured acoustic instruments, was a favorite form of entertainment and recreation on Stovall Plantation. Music was a tonic for the hard lives of the sharecroppers, and they made it any way they could. From acoustic guitars and harmonicas to a simple piece of paper folded over a comb, anything that was portable and would produce a sound could be used to make soul-restorative melodies on a break from the back-breaking labor of the cotton fields.

Along with his voice, little McKinley Morganfield made music by beating out rhythms on old kerosene cans, buckets, and a homemade "git-tar" constructed from a box and a stick. His first "real" instrument, however, was more suited to polka than the blues. "My first instrument, which a lady give me, was an old squeeze box, old accordion," Waters told "Deep Blues" author Robert Palmer. "I must've been five. I never did learn to play anything on it, and one of the older boys pulled it apart."

Waters' grandmother didn't approve of his 'sinful' music

At age seven, Muddy Waters made his first tentative steps as bluesman when he picked up the harmonica. "I was messing around with the harmonica ever since I got large enough to say, 'Santy Claus, bring me a harp.'" Waters recalled in Robert Gordon's "Can't Be Satisfied." It would take six years for Waters to master the instrument, much to the annoyance of his grandmother, who would send him out of the house when the racket became unbearable. With the help of several seasoned harp players, Waters was proficient on the harmonica by 13 and began playing local picnics and fish fries with his friend, guitar player Scott Bohaner.

However, Waters' passion for blowing the harp was at odds with his grandmother's strict religious beliefs. Church was, and is, a dominant force in the South, and music that didn't explicitly praise the Lord was frowned upon. "My grandmother told me when I first picked that harmonica up," Waters recounted, "she said, 'Son, you're sinning. You're playing for the devil. Devil's gonna get you.'"

Muddy Waters sold a horse to buy his first guitar

By the time Muddy Waters was a teen, music had become an all-consuming passion. When his grandmother bought her own phonograph, Waters scrounged every nickel he could find to buy records by his favorite blues artists. As detailed in "Can't Be Satisfied," Waters pored over the recordings of Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charlie Patton, and Son House.

At 14, Waters experienced a blues epiphany when he saw Son House play at a juke joint outside of Clarksdale. House's skill with a bottleneck slide inspired Waters to trade in his harp for a guitar. In an interview quoted by author Robert Gordon, Waters recalled the transformative moment. "I stone got crazy when I seen somebody run down them strings with a bottleneck," Waters said. "My eyes lit up like a Christmas tree and I said that I had to learn."

After some informal lessons, Waters finally bought his first guitar at 17. "I sold the last horse we had," Waters recalled to Robert Palmer. "Made about fifteen dollars for him, gave my grandmother seven dollars and fifty cents, I kept seven-fifty and paid about two-fifty for that guitar."

Muddy Waters was a moonshiner and a fur trapper

Soon after buying his first guitar, Muddy Waters began playing all-night jukes around Clarksdale. Making up to $2.50 a night, Waters quickly saved up enough money to buy a new guitar — a $14 model ordered from the Sears and Roebuck catalog.

From an early age, Muddy Waters knew he was meant for life beyond Stovall Plantation. "I always felt like I could beat plowin' mules, choppin' cotton, and drawin' water," Waters told Robert Palmer. "I did all that, and I never did like none of it. Sometimes they'd want us to work Saturday, but they'd look for me, and I'd be gone, playin' in some little town or in some juke joint."

Still, gig money wasn't steady, and Waters supplemented his income of 50 cents an hour from sharecropping with a number of odd and sometimes illegal jobs. As detailed in "Can't Be Satisfied," Waters earned extra money as a fur trapper, selling the hides of mink, racoons, and rabbits. Throughout his childhood, Waters earned money scrubbing bottles and selling them back to moonshiners. As a young adult, he learned to make and sell whiskey himself, an activity to which the owners of Stovall turned a blind eye.

A glass of water changed Muddy Waters' life

In the summer of 1941, Muddy Waters heard a rumor around Stovall that a white man was looking for him. In Waters' mind, that could mean just one thing: The authorities were onto him for bootlegging whiskey.

However, Alan Lomax (pictured) was no revenue agent. He was a 26-year-old ethnomusicologist on a mission from the Library of Congress to document the vanishing folk music of the American South. He had heard Waters was as good as the recently deceased bluesman Robert Johnson and wanted to record his music. Nevertheless, Waters still had his doubts about this strange white man. To establish trust, Lomax asked for some water and, to Waters' astonishment, shared it from the same cup from which he'd been drinking. In the segregated South, such an act was unthinkable.

As documented in "Can't Be Satisfied," Lomax set up his portable recording equipment on the porch of Water's cabin, and with a toast of Muddy Waters' moonshine, all traces of distrust melted away. Lomax recorded two of Waters' songs that day: "Country Blues" and "I Be's Troubled."

A wage dispute spurred Waters to leave Mississippi

According to "Deep Blues" by Robert Palmer, Muddy Waters was amazed at what he heard when Alan Lomax played his recording back to him. It sounded as good as any record he'd ever heard. Months later, he received a package in the mail containing two records and a check for $20. Waters immediately took one copy to Will McComb's cafe and placed it on the jukebox. Listening to his music over and over, he quietly told himself, "I can do it. I can do it."

However, "doing it" would require leaving Stovall and Mississippi behind — an act that would initially prove difficult for Waters. Waters first attempted to move to St. Louis, but he found the big city too cold and impersonal. Soon, he was back on Stovall, driving a tractor for 22½ cents an hour. Upon discovering that the other farm hands were getting 25½ cents for the same job, Waters went to overseer T.O. Fulton to ask for a raise. When Fulton angrily refused his request, Muddy Waters made up his mind to leave Stovall for good.

Muddy Waters invented electricity

Muddy Waters arrived in Chicago in 1943 with a suitcase and guitar. He went to work as a truck driver and played house parties and small clubs at night. However, the Chicago music scene was not at all what he'd expected. "Blues was dying out," Waters told Peter Guralnick, author of "Feel Like going Home: Portraits in Blues and Rock 'n' Roll." "There was nothing happening. ... It was pretty ruggish man."

Soon after arriving in Chicago, Waters' uncle Joe Brant gave him an electric guitar. To make his mark in the big city, Muddy Waters needed to be heard over the din of crowded bars and nightclubs, and the amplified instrument was just the thing. Although T-Bone Walker had used an electric guitar as early as the 1930s, Waters' use of the instrument through a cranked, distorting amplifier coupled with his signature, Son House-inspired licks transformed the instrument from mere accompaniment to the voice of Chicago Blues.

Muddy Waters assembled a band of blues all-stars

As detailed in Peter Guralnick's "Feel Like Going Home," Muddy Waters' electrified sound gained him a loyal club following, and in 1945, he caught the attention of Columbia Records. He would record songs for the label, but they were never released. Waters' recording fortunes soon changed when a talent scout from Aristocrat Records heard him. After several unsuccessful records, Waters had his first hit in 1950 with "Rollin' Stone." Aristocrat, rechristened Chess Records, would become the leading purveyor of blues music.

Just prior to the release of "Rollin' Stone," Waters assembled his first band. In the highly competitive world of Chicago blues clubs, Waters' group was second to none. Waters, along with guitarist Jimmy Rogers and harmonica player Little Walter, who would both become successful solo blues artists in their own right, were feared and respected on the club circuit. "I'd say back in '47 or '48, Little Walter, Jimmy Rogers, and myself, we would go around looking for bands that were playing," Muddy Waters told Downbeat (via "Feel Like Going Home"). "We called ourselves The Headhunters, 'cause we'd go in and if we got a chance we were gonna burn 'em."

Muddy Waters brought the Blues to Britain

In 1954, Muddy Waters had his best year ever as a recording artist. With three singles in Billboard's R&B Top Ten, including two of his biggest hits, "Hoochie Coochie Man" and "I Just Want to Make Love to You," Waters had revolutionized blues music. Yet, by 1956, blues sales were in rapid decline thanks largely to the advent of rock 'n' roll and artists such as Chuck Berry, whom Waters had referred to Chess Records just a year before.

As documented in "Can't Be Satisfied," Muddy Waters soon found himself resorting to local gigs to make ends meet. Although blues was in decline in the United States, British audiences were hungry for its gritty authenticity. British jazz musician Chris Barber and his band were hooked on Delta and Chicago blues and had managed to import real blues stars such as Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Sonny Terry, and Brownie McGhee for concerts in England, but landing Waters for a show was their holy grail.

Expecting a rustic, folk musician with an acoustic guitar, British audiences were totally unprepared for Waters' stinging electric blues when he arrived in 1958. Although some purists were turned off by Waters' wild, amplified Chicago blues, others were paying careful attention. Among this new wave of British blues devotees were Eric Clapton, Eric Burdon, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, and many others who, inspired by Muddy Waters, would bring the blues back with a vengeance in the 1960s.

A 1960s attempt to repackage Waters as a rock artist failed

As the 1960s unfolded, British bands like the Rolling Stones (who took their name from a Muddy Waters song) covered Waters' songs, opening his music up to a new generation of young fans. From The Animals to The Yardbirds, British blues became the sound of rock 'n' roll in the 1960s, with loud electric guitars as its driving force. Although the emergence of rock had nearly ended his career, Muddy Waters' influence would mark its continuing evolution.

However, an attempt to modernize and repackage Waters as a rock artist failed with the 1968 release of "Electric Mud." The brainchild of Marshall Chess, son of Chess Records founder Leonard Chess, "Electric Mud" placed Waters and his Chicago blues in the midst of late '60s heavy rock fuzz and psychedelia. According to biographer Robert Gordon, Waters had misgivings about the project from the beginning, but knowing that you "don't cross the boss," he merely shook his head and went along.

Although "Electric Mud" initially sold well, it was panned by critics. No one was as hard on the experimental album as Waters himself, who said, "That Electric Mud record I did, that one was dogs***. But when it first came out, it started selling like wild, and then they started sending them back. They said, 'This can't be Muddy Waters with all this s*** going on — all this wow-wow and fuzztone.'"

Muddy Waters played his final shows with rock royalty

As detailed in "Can't Be Satisfied," Muddy Waters appeared in what would be his last recorded performance on November 22, 1981. Taking the stage at Buddy Guy's Checkerboard Lounge, Waters was joined by the Rolling Stones. Trading vocals with Mick Jagger on "Hoochie Coochie Man," a frail-looking Waters nonetheless held his own with the worshipful English rocker.

Shortly after the historic performance, Waters, a long-time sufferer of hypertension, collapsed. Diagnosed with cancer, he underwent surgery to remove part of his lung. Waving off chemotherapy, Waters' cancer went into remission, and he was well enough to take the stage again in late spring 1982. On June 30, 1982, Waters surprised Eric Clapton onstage in Miami, joining him for a performance of Waters' classic "Blow Wind Blow." It would be his final performance.

Upon returning to his Chicago home, Waters began coughing up blood. His cancer was back, and it would worsen over the course of a year. On April 30, 1983, just over three weeks after his 70th birthday, McKinley Morganfield, better known as Muddy Waters, the father of Chicago blues, died of cardiorespiratory arrest and carcinoma of the lungs.