Messed Up Things That Happened During The American Civil War

Warfare distorts the normal rules of behavior and suspends some basic, fundamental laws—such as the laws prohibiting us from killing each other. Combined with the psychological pressure of constant danger and overt violence and the "fog of war" that clouds decision-making, it isn't surprising some pretty messed-up stuff happens both on and off the battlefield.

The American Civil War is was the first so-called modern war, and is still one of the bloodiest in history. Although it took place a century-and-a-half ago, it's still recent enough that the people, technology, and events are recognizable to modern-day citizens. This is helped by the fact it's one of the earliest major conflicts that was recorded in photographs and near-instant works of journalism, giving the war an immediacy that earlier histories lack.

But just because the iconography of the war seems familiar doesn't mean it didn't suffer from the distorting effects of brutal violence. The Civil War definitely affected people's morality and good judgment—put simply, people did stuff during the Civil War that leaves you shaking your head in wonder. Here are some of the messed-up things that happened during the American Civil War.

Worst picnic ever

The fact is, no one knew what to expect about the Civil War. Everyone assumed the old rules about warfare would still apply because they couldn't predict how the industrialization of weaponry and advances in munitions and tactics would play out.

Of course, even allowing that people couldn't know just how brutal and bloody the war was going to get doesn't quite explain the decision some made to show up to the first battles with picnic baskets and a couple of friends like they were going to a 19th-century version of Burning Man. But as History.com tells us, that's exactly what some people—including several members of Congress—did on July 21, 1861, at Manassas, Virginia, where what would be known as The First Battle of Bull Run took place.

As HistoryNet reports, journalists and propagandists had been hyping up the battle for the three months a state of war had existed between the Union and the Confederacy, and the battle took place on a bright, sunny Sunday, so hundreds of people packed lunch and opera glasses to go watch. The expectation was that the North, wealthier and more advanced, would easily defeat the Confederates and the war would be over quickly—possibly even that day. When the battle became bloodier than expected and the Southern forces turned the tide, the Union retreated in chaos and the picnickers had to run for their lives.

No way to die

The main reason the American Civil War is sometimes referred to as the first modern war has to do with technology: Guns and ammunition were not only more accurate than ever, but they were also easily mass produced for the first time in history. When you hear the Civil War was incredibly bloody, with more than 600,000 casualties, it's easy to assume most of those folks died from bullet wounds. But you'd be wrong.

As PBS reports, about two-thirds of the deaths in the Civil War are attributed to disease, not bullets. When you realize the whole "modern war" business has nothing to do with medical knowledge, it starts to make sense: The doctors working in the field hospitals didn't have any understanding of germs or how bacteria caused diseases, and sanitation and food purity were horrifyingly primitive. The end result was hundreds of thousands of soldiers dying slow, agonizing deaths.

Not understanding how germs worked meant the most common way a Civil War soldier in either army died was due to gastrointestinal diseases. WVTF notes that of the roughly two million men who served in the Union Army, 1.9 million reported severe diarrhea at some point—most likely a symptom of dysentery. One other reason it was so deadly: Physicians typically made the disease worse by prescribing treatments that actually worsened the disease.

Misery as entertainment

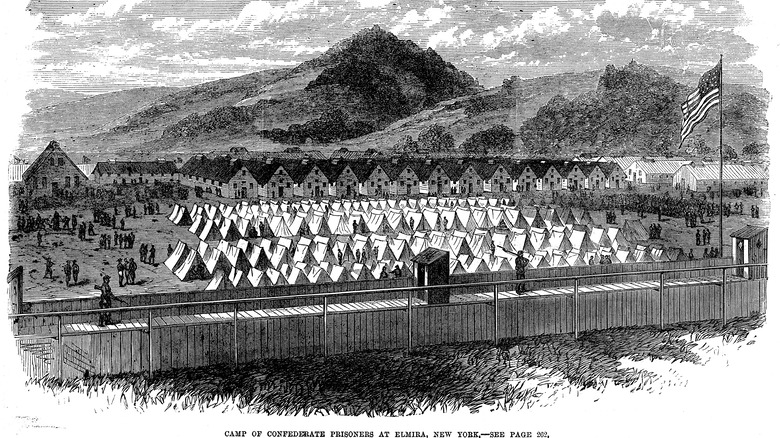

When people talk about the horrors of the American Civil War, they tend to focus on the battles and the casualties. The truth is, some of the most horrifying aspects of that conflict stem from the way both sides treated prisoners of war. Military prison camps during the Civil War were some of the worst places ever conceived—the American Battlefield Trust tells us in Andersonville prison alone 13,000 men out of 45,000 died far away from any battlefield.

The North was just as bad. In fact, conditions at Elmira Prison Camp in New York were so bad Ithaca.com reports that nearly one-fourth of all the men imprisoned there died. Prison camps became dangerously overpopulated because the Union Army didn't want to exchange prisoners or parole Confederate soldiers because they knew they had a manpower advantage. In short, the North figured it could starve the South of men. In Elmira, conditions were horrifying, with an open pond used as a collective latrine, leading to an explosion of diseases.

But historian Michael Horigan reports the most messed-up thing about the suffering men in Elmira: The good people of New York set up viewing towers and charged 10 cents to watch the prisoners be brutalized. The prisoners started doing little performances for the crowds—until the guards put a stop to it. The people kept paying to watch the Confederates slowly die of disease and general abuse, and the observation towers were popular—and crowded.

License to kill

War is all about killing, but even in times of warfare it's generally expected law and order will prevail outside the battlefield. Even soldiers aren't supposed to just casually murder someone when on leave from their units.

Unless you're an experienced and competent Civil War general, that is. As Country Roads Magazine reports, General Jefferson C. Davis (no relation to the President of the Confederacy) was considered a slightly-above average commander, and was placed under the command of General William "Bull" Nelson in the defense of Louisville, Kentucky. Nelson grew dissatisfied with Davis, and basically fired him. A few days later Davis ran into Nelson in a hotel lobby, called for a pistol, and murdered him in broad daylight, in front of many, many witnesses.

As HistoryNet reports, Davis was arrested—but never actually charged. In Washington, D.C. it was recommended Davis be court-martialed, but this was rejected by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Davis continued his career in part because the Union Army, still floundering in 1862, simply couldn't afford to lose anyone who knew what they were doing. Even after the war no one seriously pursued justice for Nelson, and Davis went on to be named military governor of Alaska when the United States purchased that territory from the Russians.

Glowing wounds saved lives during one Civil War battle

As noted by PBS, the state of American medicine in the middle of the 19th century was pretty terrible, even compared to other countries. There was no concept of germ theory, or that sanitation or handwashing could have an impact on infection rates and recovery. As eHistory notes, the most common surgery performed by Civil War doctors was amputation, because there was no other reliable treatment for most wounds.

So when more than 20,000 soldiers lay in the bloody mud after the Battle of Shiloh—one of the bloodiest of the war—it's easy to assume most died of their wounds or complications thereof. Except, as All That's Interesting notes, these wounded soldiers experienced a much higher survival rate, and a lower infection rate. They also noticed that while laying in misery at night, waiting for rescue, their wounds ... glowed.

Called the Angel's Glow, this life-saving phenomenon remained unexplained for nearly 140 years. As reported by Promega Connections, in 2001 two students realized the soldiers' wounds were likely contaminated with a bacterium known as Photorhabdus luminescens, which glows in the dark and only grows under very specific conditions—which would have existed the night after the battle. The bacteria releases toxins that inhibit the growth of other organisms—thus saving the soldier's lives by preventing secondary infections.

The serial revenge sniper

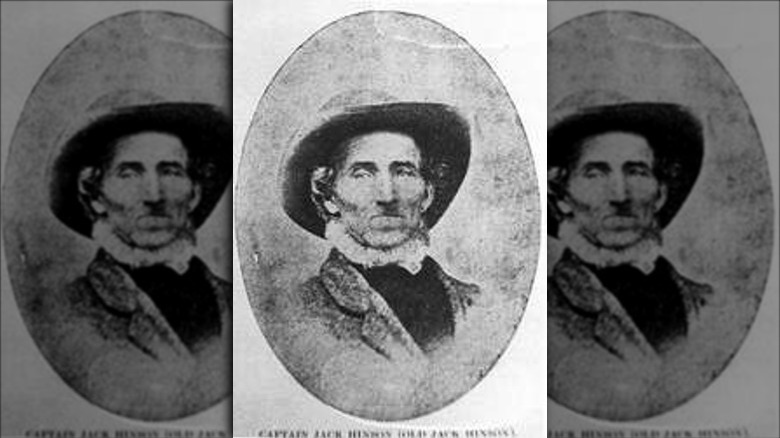

One thing is always true: Once you train someone to be an effective soldier, they have a skill set that can be easily applied to other pursuits—usually criminal in nature. Sometimes, though, someone skilled at killing people will use those skills to pursue something else: Revenge. Jack Hinson was that person in the American Civil War.

As reported by OZY, Hinson lived with his family on the border between Kentucky and Tennessee. Although his sympathies lay with the South, he was firmly anti-secession and tried to stay neutral. His two sons were captured while out hunting, however, and after being summarily executed as suspected Confederate guerrillas a sadistic Union officer had their heads cut off and mounted on Hinson's fence as a warning.

As you might imagine, this didn't endear Hinson to the Union army. Hinson was no soldier, but Guns.com tells us he was an experienced hunter and expert marksman. He ordered a special gun, a .50 caliber Kentucky Rifle with a barrel 41 inches long, capable of hitting targets from half a mile away in the right hands. And Hinson had the right hands. He embarked on a cold-blooded murder spree to avenge his two boys, and it's estimated Hinson executed as many as 100 Union officers by sniping them with terrifying accuracy. The Union Army eventually designated four regiments to hunt Hinson, but he was never captured, and died peacefully in 1874.

The national hero who castrated himself

Boston Corbett has to be on any list of messed-up stories about the American Civil War. As noted by The New England Historical Society, Thomas Corbett moved to Boston as a young man, where he became an enthusiastic member of the Methodist Church. He changed his name to Boston and became well-known as a street preacher—a preacher more than happy to throw hands with anyone who disagreed with him.

Corbett worked as a hatter, which many suspect exposed him to dangerous chemicals that affected his mental health (a real thing known as Hatter's Disease). The Washingtonian tells us one day Corbett was accosted on the street by a pair of prostitutes, and was disturbed by his, um, automatic reaction. So he went home and castrated himself using a pair of scissors. Amazingly, after the procedure he went out to a prayer meeting, had a leisurely dinner, and only then went to a hospital.

Corbett might have been just a local legend if it weren't for the events of 1865. After serving in the Union Army, being captured and serving time in the notorious prison camp Andersonville, he was part of a regiment sent to track down John Wilkes Booth in the wake of Abraham Lincoln's assassination. Corbett shot Booth against orders because he believed it was what God wanted. Corbett was a celebrity for a while, but slowly faded from public view, his health deteriorating. He vanished without a trace in 1894.

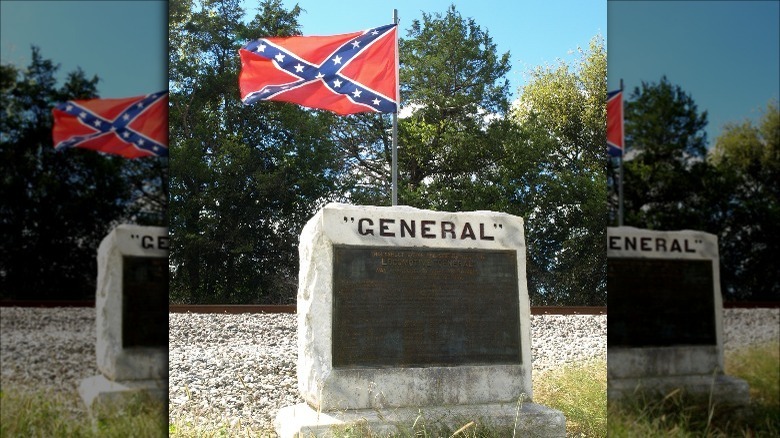

The Great Locomotive Chase

If you're curious what people did for entertainment in the ancient times before there were Fast and Furious movies, all you have to hear is one word: Trains. American heritage reports that in April 1862, a Union Army officer named Lieutenant A. L. Waddle asked for volunteers to go on a dangerous mission behind Confederate lines. Twenty-three men eventually joined the mission, which was intended to disrupt and damage the railroad lines in the South, which were pretty sparse and poorly laid out—with just one line linking the eastern and western portions of the Confederacy.

The National Medal of Honor Museum recounts the mission: Wearing civilian clothes and led by a mysterious civilian guide named James J. Andrews, the team bought tickets and boarded a locomotive called the General. When the train arrived at Kennesaw, Georgia—a town with no telegraph capabilities—they hijacked the train and began moving north, ripping up the tracks behind them and cutting the telegraph lines—which prevented the Rebels from warning anyone further up the tracks.

The Confederates chased them, first on foot, then in a series of their own trains, but only caught them when the General ran out of fuel. When they finally caught up, eight of the men were executed. Nineteen soldiers involved received the first ever Medals of Honor.

The youngest soldier of the Civil War

We tend to think of warfare as an adult endeavor, and the American Civil War is no exception. But as PBS points out, the Confederate Army had no age limit and the Union Army routinely overlooked its age requirements. In fact, it's estimated as many as 20% of the soldiers on the field were younger than 18.

That's horrifying enough, but the most shocking story is probably John Clem. Ohio History Central tells us joined the Union Army when he was just 10-years-old. As the American Battlefields Trust reports, Clem was rejected by several units due to his age before being accepted into 22nd Michigan Infantry Regiment. He was too young to be officially on the roster, so the soldiers of his unit scrounged up money to buy him a uniform and a gun, training him to be their drummer boy. In fact, most children serving in the war started off as company musicians.

Clem proved to be a fierce little guy. At the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, Clem found himself surrounded by Confederates and cut off from his unit. The enemy soldiers were reportedly amused by Clem's tiny frame—until he shot an officer and then fought his way back to the regiment. He became famous as the Drummer Boy of Chickamauga. Clem remained in the army his entire career, retiring in 1915 as a 2-star General, the last-active duty Civil War veteran.

The deadliest ammunition of the Civil War

The carnage of the American Civil War was shocking to everyone at the time. The explanation is simple: Weapons technology had advanced rapidly, medical and basic sanitation practices had not. As The New York Times explains, the introduction of the rifle musket changed how armies fought. Its increased accuracy and ease of loading meant soldiers in the Civil War didn't have to march up close to each other to fire—they could kill each other from much further away, at a much faster pace. But what elevated the new weapons from merely deadly to nightmarish was the ammunition they used: The minié ball.

As explained by HistoryNet, the minié ball was designed to be conical instead of spherical, with a hollow base that allowed it to be slightly smaller than the rifle's bore, making it easy to load. When fired, the base expanded to be grooved by the rifling, making it accurate over long distances. And its soft, expandable nature meant that when it hit a soft target like a human being, it deformed and shattered, causing incredible damage that led to amputations and slow, agonizing deaths.

According to the Gettysburg Compiler, the invention of the minié ball changed battlefield tactics—and was directly responsible for the incredibly high casualty rate of the Civil War. And its deadly effect was entirely unintentional.

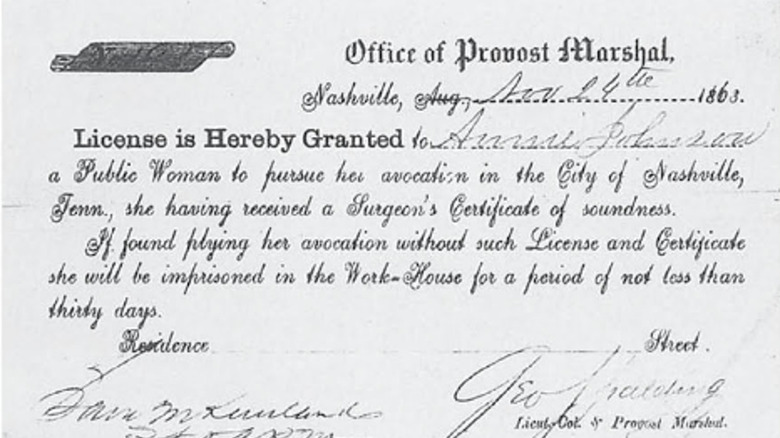

The army-administered brothels of Nashville

Something that is often overlooked when discussing the American Civil War is the impact of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). According to the Dittrick Medical History Center, there were more than 100,000 sexual misconduct charges levied against just Union soldiers alone, and nearly 200,000 cases of venereal disease documented—again, just in the Union Army alone.

As History.com notes, some Union Army leaders in Nashville tried to solve the problem by rounding up every sex worker they could find—over 100 of them—and forcing them onto a boat to be shipped north, reasoning that if there were no sex workers, there would be no more sexually transmitted diseases. When no other port would accept the ladies, however, it was big brain time for the city of Nashville: They legalized sex work. The Union Army established a hospital to treat sex workers for venereal diseases and required they apply for a license and submit to regular health assessments.

And it worked. The rate of STDs plummeted, and the program proved so popular it was adopted by nearby Memphis. If the program had been known outside of Tennessee, the history of sex work in this country might have been very different, but after the war ended the Army stopped the experiment, and everything went back to status quo ante bellum.

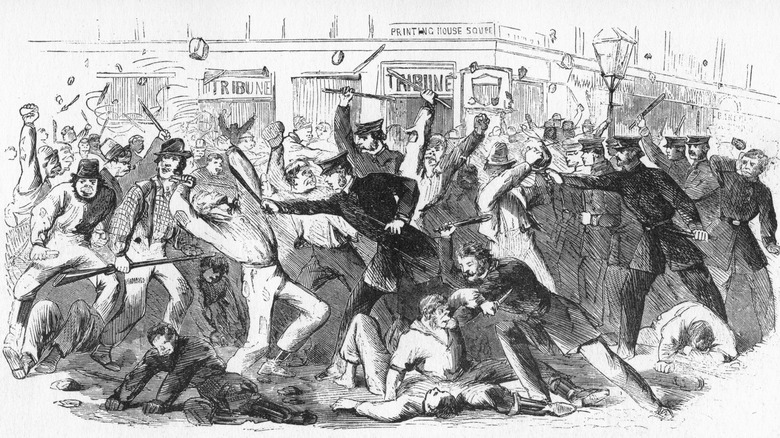

The draft and the riots

The people of New York City weren't exactly united in their support of the Union. As History.com explains, New York did a lot of business with the South, and there was even talk of joining the Confederacy. As the war dragged on, anti-war interests told the working classes in the city that if the slaves were freed, they would surge north and take their jobs.

So the city was already in turmoil when The Civil War Military Draft Act was enacted in the summer of 1863. As Smithsonian Magazine explains, this was the first-ever involuntary draft in U.S. history and it was immediately controversial. The final straw for the working class folks of New York City was the provision in the law that allowed men to hire replacements—or simply pay the government $300 to be excused. Most workers might earn that in a year; it was clearly a benefit for the wealthy.

So, New Yorkers did what you might expect: They rioted. For four days there was widespread violence and destruction—and the truly messed-up part was a lot of the violence was directed at the Black population, both because of fears they would take everyone's jobs and because as non-citizens they were exempt from the draft. The riots spread to other cities, but New York was the epicenter. While the official death count was 119, historians agree the true death count was closer to 1,200.