The Untold Truth About The Lincoln Highway

Most Americans are fairly familiar with our interstate highway system, but most don't know that there was a transcontinental highway that predated it: the Lincoln Highway. It began development in 1913, five years after the release of Henry Ford's Model T (via Ford), and crossed the United States from New York to San Francisco, according to the Lincoln Highway Association (LHA).

At the turn of the 20th century, there were few paved roads, writes Pennsylvania Center for the Book (PCB). Dirt tracks meant for horse and wagon were hard to travel on with the new automobiles, and with no set system of roads to connect one place to another, traveling coast to coast could easily take two to three months. Rapid technological automotive breakthroughs meant that cars were able to drive faster than it was safe to do on dirt roads, notes The Indianapolis Motor Speedway (IMS).

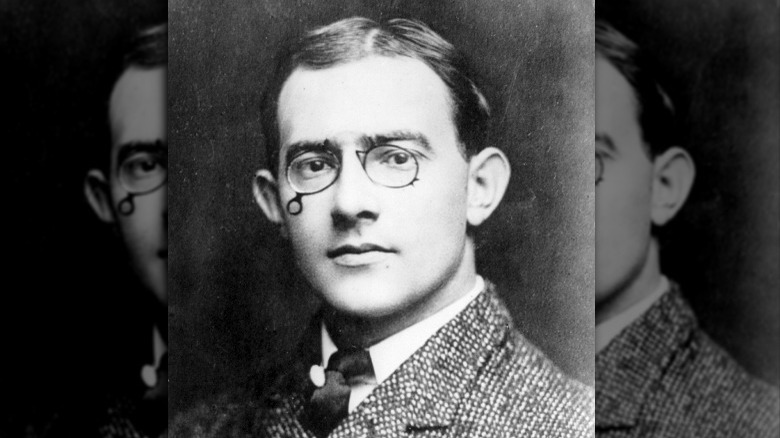

The Lincoln Highway was the brainchild of Carl G. Fisher, who said its goal was to "stimulate as nothing else could the building of enduring highways everywhere that will not only be a credit to the American people, but that will also mean much to American agriculture and American commerce," via the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

"In its time, the Lincoln Highway would become the nation's premier highway, as well known as U.S. 66 was to be in its day and as well known as I‐80 and I‐95 are today," notes Richard Weingroff of the FHWA.

Selecting the route was the first important decision

When Carl Fisher, who also was part of the partnership that built the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, the LHA notes, came up with the idea to build it, he originally called it the "Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway" and looked to industry leaders to help fund the approximately $10 million required. Frank Seiberling and Henry Joy, presidents of Goodyear and Packard Motor Car Company, respectively, pledged their support, and it was Joy who suggested they name if after Abraham Lincoln, as Congress at that time was discussing funding for what would become the Lincoln Memorial. To help move the project forward, Fisher created the Lincoln Highway Association in July 1913.

When choosing the route, the LHA noted, the builders aimed to create the straightest, most direct route they could, utilizing existing roads when possible. Therefore, they avoided many larger cities. In the end, the route goes through 13 states: New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California. A San Francisco Examiner article on Oct. 31, 1913, quoted in reporting by the Oakland Tribune, raved about its potential. "The Lincoln Highway, which promises to be a lasting monument to the automobile industry and one of the greatest developments ever made in this country, will be officially dedicated tonight by every city, town and hamlet between New York and San Francisco." While some of the roads were paved, some not, by 1915 drivers were able to make the entire trek coast to coast.

In 1915, the LHA published a Complete Official Road Guide to the Lincoln Highway to aid travelers, detailing routes, destinations, recommended supplies, and what they would encounter.

Mechanical problems were challenging to deal with

Anyone going on a long road trip tries to be prepared for any eventuality, but with early cars, like the ones that would have driven the Lincoln Highway, owners had to be prepared to be not only driver but mechanic. According to Ford, when Model T cars were first released, the company included a tool kit for people to fix the car themselves as they needed.

There were no tow trucks when the highway opened either, as the first tow truck, DriveZing writes, was built in 1919. Even if you were able to stumble your broken down jalopy into a nearby town pulled by horses, car mechanics were hard to come by, and many were run by blacksmiths or bike repairmen, notes the National Museum of American History.

Getting gas was also an issue. While automobile "filling stations" had been around since 1905, writes the American Oil and Gas Historical Society (AOGHS), there was the challenge of distance and availability. The LHA noted in its 1916 Road Guide, "Don't wait until your gasoline is almost gone before filling up. There might be a delay, or it might not be obtainable at the next point you figured on." While the Model T got 13-21 mpg, MotorTrend reports, the gas tank only held 10 gallons (via Britannica), so the LHA Road Guide also advised travelers to carry an extra gas tank in case of emergencies.

Over time, enterprising mechanics and entrepreneurs set up garages and gas stations adjacent to the highway, like the Cooper and Hostert Garage in Mokena, Illinois, that opened in 1916 (via Enjoy Illinois).

Lodging was also an issue

In the days before Holiday Inns or KOAs, finding a place to spend the night was also an issue for those traveling the highway coast to coast in the early days, when, as USA Today notes, there weren't many lodging opportunities for travelers. There were some, like the Lincoln Hotel B&B in Lowden, Iowa, which was built in 1915, writes Travel Iowa, but in some areas they were few and far between. The LHA Road Guide noted counties and towns with no tourist accommodations.

Because of that, people become innovative. Tents were created that would attach to the side of the car, and then collapsible cots were set up inside, writes USA Today. Camp chairs and foldable tables would be brought along as well. With few official campgrounds, travelers often just camped wherever was convenient (via The Henry Ford).

Eventually, as with mechanics, campgrounds and other lodging options began springing up along the highway. Towns along the route, wanting to encourage travelers to patronize businesses in the area, created municipal campgrounds, and there were over 500 municipal camps in the U.S. by the 1920s, writes the city of Aurora, Illinois.

One particular development was the creation of motor courts. A precursor to our modern hotels and motels, motor courts had one large central building surrounded by small, standalone cottages (via Road Trippers). Few survive today, but the Lincoln Motor Court in Manns Choice, Pennsylvania, built in the 1940s, is the last motor court on the Lincoln Highway still taking overnight guests in its restored bungalows.

Eventually the federal government got involved

With the passage of the Federal Aid Road Act in 1916, the government began providing funding to improve any road used by the Postal Service to deliver mail, according to the FHWA. It also required states to create their own highway departments to maintain the roads in order to get the federal funding. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1921 increased the funds and set down new parameters, including that paved roads had to be 18 feet wide at a minimum. Some of those funds were used for building what is known as the "Ideal Section," a 1.3-mile model part of the Lincoln Highway in Indiana designed to meet the area's traffic needs for the next 20 years. It is believed this was an experiment to try out ideas that would later be used in the interstate highway system.

In 1925, the Secretary of Agriculture created the Joint Board on Interstate Highways with an intended purpose of creating a system of uniform road numbers and signs, the FHWA writes — including "STOP" signs and the shield-shaped Route markers. States started implementing the system after approval in November 1926, and colloquial names for those roads, like the Lincoln Highway, were replaced by numbers. The LHA notes the Lincoln Highway now follows sections of U.S. Routes 30, 40, and 50.

With the government's involvement, the Lincoln Highway Association discontinued operations by 1928 (via LHA). As a final project, on September 1, 1928, Boy Scouts from all over the country placed 2,436 commemorative markers across the old Lincoln Highway, all in a single day, memorializing both the highway's importance in American history and honoring Abraham Lincoln. Some of those markers can still be seen today along the original highway routes.

The Lincoln Highway turned 100 in 2013

In 2013, the town of Kearney, Nebraska, approximately the halfway point between the coasts, hosted a centennial celebration of the Lincoln Highway, with a parade, vintage car show, and other activities, writes Kearney Hub. Two different groups of Lincoln Highway enthusiasts followed the original highway heading for Kearney to arrive in time for the celebration on June 30, leaving from the original endpoints: Lincoln Park in San Francisco and Times Square in New York (via the LHA).

Just south of Chicago, artist Jay Allen painted a series of nine different murals, finished in 2012 to be ready for the 100th anniversary in 2013, according to Visit Chicago Southland. They depict different moments in the history of the Lincoln Highway, both local to Illinois and across the country.

In 1919, the summer after the end of World War I, the Army took a convoy of 81 vehicles across the Lincoln Highway from D.C. to San Francisco (via the FHWA) The intended goal was to check the Army's ability to mobilize vehicles from one location to another in a wartime scenario, still fresh on everyone's minds. It took 61 days over then-still rugged roads, with numerous vehicle breakdowns. In a notable twist, Dwight D. Eisenhower, then an officer in the Army, was part of the convoy, and 34 years later that experience would influence his support as president for developing the interstate system. "The old convoy had started me thinking about good, two‐lane highways, but [the autobahn in] Germany had made me see the wisdom of broader ribbons across the land," Eisenhower wrote in his book, "At Ease."