The Truth Behind The Migrant Mother Photographer

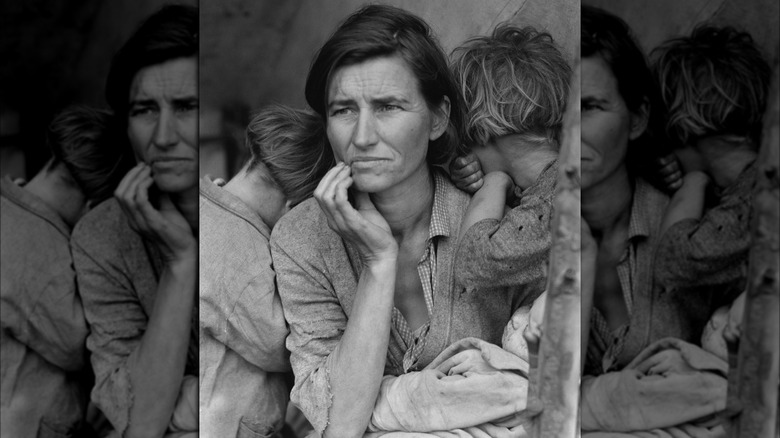

It's no exaggeration to call the photograph "Migrant Mother" one of the most iconic images of the Great Depression. Flanked by two of her young children, their faces hidden, while she holds a third child, an impoverished Cherokee farmhand stares stoically into the distance, her hand placed ambiguously on her chin (via PBS). Its use has become almost a cliché in history textbooks that mention the Dust Bowl, which has blunted its power somewhat, but it's a cliché for a reason: because, in a single image, photographer Dorothea Lange captured the essence of the Depression-era working poor. It's an image of strength, doubt, worry, resolve and resignation all at once.

It's an unforgettable image, but it's far from the only image produced by Lange, who lived into the mid-1960s and only got more prolific as she aged. She captured history as it happened and traveled the world, photographing people as they were — empathizing with them without romanticizing their plights. This is her story.

Dorothea Lange originally set up shop as a commercial portrait photographer

Born Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn in 1895 in Hoboken, New Jersey, Lange was raised in a fairly typical middle-class family for the time. At age 7, she contracted polio, which left her walking on a weakened right leg for the rest of her life. According to The Art Story, Lange maintained that her bout with the disease was what kept her humble all her life, calling it "the most important thing that happened to me, and formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me, and humiliated me." When she was 12, her parents divorced — an eventuality that she blamed on her father, leading her to take her mother's maiden name as her own.

As early as high school, Lange showed little interest in academic pursuits, and after graduation, she studied photography under Clarence White at Columbia. White was an early photography professor who encouraged his students to photograph everyday objects in order to really "see" them.

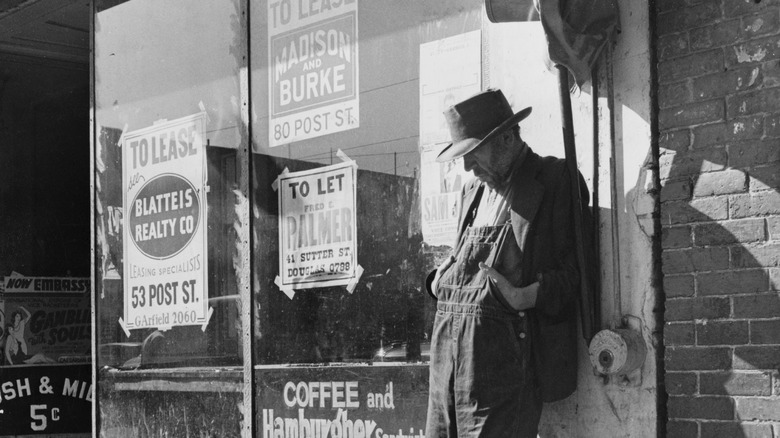

Settling in San Francisco in 1918, Lange set up shop as a portrait photographer, and eventually married mural artist Maynard Dixon. Lange saw her portrait work as a trade, not an art, and focused mainly on satisfying the desires of her clients — until the Great Depression hit, and everything changed for her. Suddenly her marriage was on the rocks and her business was dwindling, and Lange grew increasingly frustrated with the mundanity of commercial portraiture. She took to the San Francisco streets to document the plight of the out-of-work common man (via PBS).

It was capturing the Depression that really launched Lange's career

It was Lange's photographs of the working class plight that led to her commissioning by the Farm Security Administration, part of FDR's New Deal. She was recruited to document the plight of migrant workers by economist Paul Taylor, who also became her second husband. As part of the FSA, Lange drew deeply from her portraiture techniques to capture people as they were, but also to delve into their deeper essence. Lange's photos for the FSA were often captioned with quotes from her subjects, giving literal voice to the people (via Britannica). In 1940, Lange became the first female photographer to win the Guggenheim Fellowship for her work.

As the Depression gave way to World War II, Lange turned her attention to documenting the internment of Japanese-American citizens, where her portraiture techniques would continue to serve her. As the war came to a close, though, Lange became disillusioned by her political photography's failure to effect real change, and withdrew from the public sphere for most of the 1950s.

Lange found her way back to the art of photography eventually, however, when Taylor became a foreign diplomat. She traveled the world with him, and captured the conditions in countries around the world, many of which were more dire than those she had witnessed during the Depression.

In 1965, Lange was rewarded for her work with a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, which she worked tirelessly to curate from her life's work. She died a mere three months before the retrospective opened, but she left behind an incredible body of work and an entire artform that would never be the same again.