Here's What It Was Really Like For Prisoners In The Bastille

The Bastille is a menace. It's a notorious hallmark of the French Revolution, the dank, dark prison where the enemies of the king were thrown whenever they got too vocal. And, when things grew to a fever pitch and the guillotines started to appear, a crowd of angry, populist Parisians appeared to break down the walls of this notorious place, free the prisoners inside, and kick start their revolution.

Only, it didn't exactly happen that way. While it's true that the Bastille was stormed on July 14, 1789, per the British Library, it's not necessarily correct that the crowd was tearing down a notorious torture dungeon. There's certainly no denying that the Bastille was a prison that was used to incarcerate undesirables, but things get more complicated when you move past the surface.

Being a prisoner in the Bastille, as it turns out, could be surprising even for the people being sent there. Generally speaking, they couldn't leave, but, as author Geri Walton reports, they could also access a prison library, attend church, and even bring in their own stuff — including, in some cases, their own personal servants. That's because, for much of its history, the Bastille was a prison for upper class offenders. Even if an inmate wasn't loaded or didn't had a refined pedigree, they could still encounter some surprising facts of life as a prisoner of the Bastille.

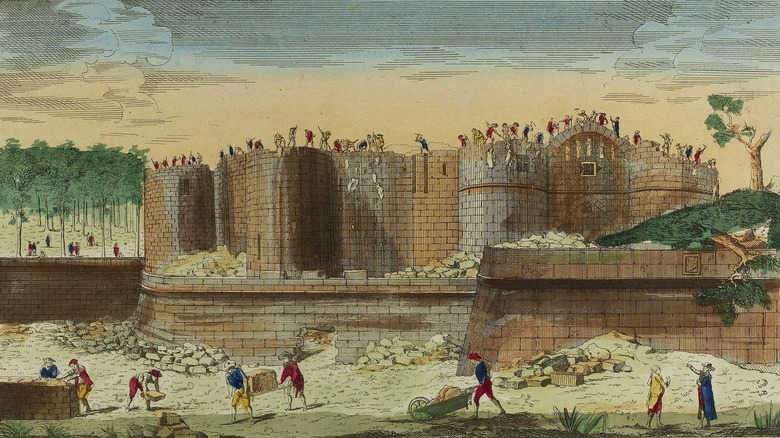

The Bastille wasn't always a prison

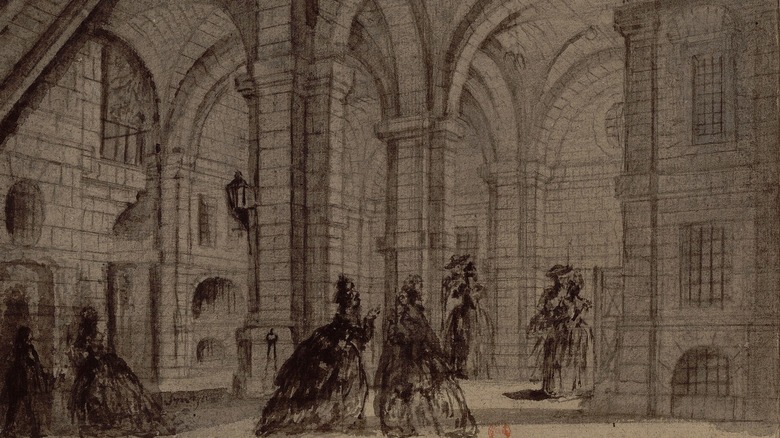

Though it's come down in history as an infamous, darkly imposing prison, the Bastille wasn't originally intended as anything of the sort. Instead, according to ThoughtCo, it was originally built as a defensive structure for 14th century Paris. That's when English forces would have been potentially bearing down upon the capital of France during the Hundred Years' War. As such, it would have been ready to withstand a serious assault, explaining the five-foot thick walls that reached over 70 feet in height. Undoubtedly, it would have also presented a formidable impression to any approaching soldier who had been ordered to breach its walls.

The Bastille wouldn't be used as a prison until Charles VI's era, as The Telegraph reports, in 1417. Still, that use appears to have been pretty piecemeal until the 17th century brought in more eager monarchs and officials who were ready to turn the Bastille into a truly notorious prison.

Some monarchs used it as a political prison

The true heyday of the Bastille as prison didn't come until the 1600s, when Cardinal de Richelieu, a powerful government minister, began to use the fortress as a tool to systematically imprison and control inconvenient people. "Legends of the Bastille" even goes so far as to call Richelieu that "founder of the Bastille" as we understand it now. It was Richelieu who put the Bastille under the control of a proper jailor. Under his influence, the Bastille became a palace where prisoners of relatively high rank were detained, sometimes indefinitely, alongside accused spies, military personnel, and some prisoners of war.

Later kings used the Bastille to imprison high-ranking people. As National Geographic reports, Louis XIV often used the infamous lettres de cachet, or direct orders from the king that could condemn someone to a term in the Bastille. Soon, the prison became a kind of storehouse for inconvenient people, whether they were political dissidents or troublemaking members of noble families.

In general, says The History Blog, the Bastille was an opportune dumping ground for society's undesirables. These included not only vocal political dissidents, but Protestants, sex workers, and LGBTQ+ people who were deemed unfit for French society of the time.

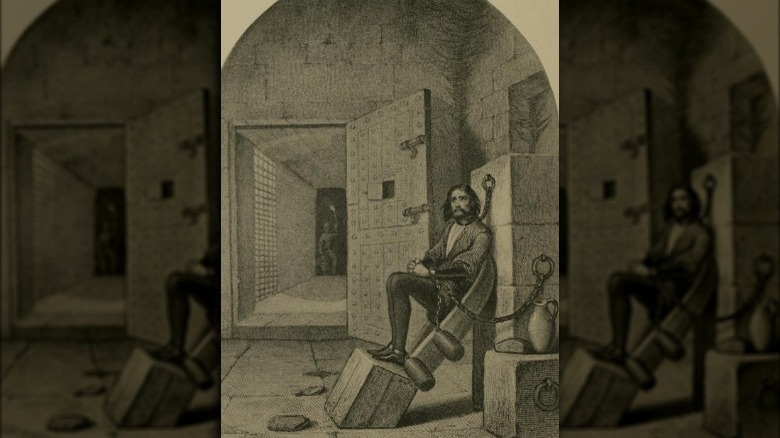

Conditions in the Bastille varied somewhat

Compared to other prisons that were around at the 17th and 18th century height of the fortress, a stay in the Bastille generally wasn't so bad. However, your experience could vary greatly depending on the exact location of your cell.

Author Geri Walton reports that the dungeons were probably one of the worst parts of the prison, as they were damp and full of vermin. Meanwhile, the rooms at the top of the Bastille, while likelier farther away from the rats, were also closest to the poorly insulated roof and all the weather just beyond. The best spots were right in between. Unless the prison was truly crowded, prisoners were most likely to be housed in the middle floors, which were generally the most comfortable ones in the place.

As for the rooms themselves, most of them had stoves to keep the occupants warm, and windows, though any openings that would have helped a prisoner escape were covered with a secure grate. The History Blog also notes that, despite the comfort of a heating system and an actual bed in each cell, the Bastille was nonetheless still a prison where inmates were locked in by guards and access to the outside world was restricted.

Bastille prisoners enjoyed surprising privileges

Once prisoners were inside the Bastille, their living conditions could prove surprising. High-ranking prisoners, who made up a pretty significant number of the Bastille's inmates, could live a relatively comfortable life, all things considered. According to "Life in the Bastille," prisoners had the opportunity to send for their own furniture and decorations, packing their cells with fine textiles, comfortable chairs, their personal libraries, and more. Many prisoners hung tapestries in their cells, bringing in a bit of color and presumably also some warmth to their rooms in an era before central heating.

The Chicago Tribune further notes that some prisoners even imported musical instruments and personal servants. The Marquis de Sade, one of the more infamous prisoners at the Bastille, brought in his own wine because he wasn't a fan of the prison's vintage and spent much of his time writing on paper brought in by his presumably very patient wife. Perhaps most importantly, there's no real record confirming that anyone was ever tortured at the Bastille, despite lurid tales from later centuries of torture dungeons.

New Bastille prisoners went through serious questioning

Newly minted inmates of the Bastille were first subject to what could be a pretty intense round of questioning. Author Geri Walton reports that this examination, as it was called, was supposed to take place soon after the prisoner entered the Bastille. However, sometimes there was a delay that added up to weeks, presumably frustrating indeed for someone who was truly innocent and stood a chance of proving it. After all, if the results of the questioning persuaded the lieutenant of the police that the inmate didn't belong there, they would theoretically be released.

Even if someone were confident of their innocence, the questioning was undoubtedly pretty creepy. By the 18th century, this process appears to have sometimes relied on an extensive intelligence network. As The International History Review reports, the France of Louis XIV was full of spies, including observant agents working in upper class circles in Paris and beyond. Some directly sent prisoners to the Bastille, including the author of a slanderous poem about the royal family who blabbed to friends that he had written the offending lines. The friends turned informants, according to Smithsonian Magazine. And so the poet in question — now known to us as Voltaire — was sent to the Parisian prison.

Pensions actually paid out to some prisoners

Though it's pretty clear that people weren't lining up to enter the Bastille, there were some added benefits to a sentence spent there, assuming you had the patience to wait for a few years. If you played your cards right at the Bastille, you might even come out with a payment in your favor.

As "The Bastille" notes, a pension was set aside for the prisoners there. At 10 livres per person, per day, it was possible for some to consume just a portion of their food. If they could manage that, then they would be paid the difference — right out of the king's budget, no less — when they were released. And if they needed clothing or medical care, including highly trained specialists, that was also provided for at no cost to the inmates.

"Legends of the Bastille" even maintains that some prisoners asked to stay there just a little while longer in order to earn some extra money. However, this appears to have been only a temporary scheme. As the 18th century progressed, the payouts stopped, and prisoners would either have to use up that pension while they were incarcerated or lose it.

Bastille prisoners could visit a library and write

Perhaps one of the worst things about prison is the sheer, stultifying boredom of the experience. Even for the rather pampered inhabitants of the Bastille, the fact that they were confined to the same restricted space for years on end was surely galling, if not crushing. But there was relief, assuming that a prisoner could read and write. Beginning in the 17th century, "Legends of the Bastille" says, prisoners could visit a hodgepodge library within the prison. However, it was incomplete, being made up generally of donations from former prisoners and the occasional warm-hearted citizen on the outside. There were apparently plenty of religious volumes, along with some light fiction and tomes on science and philosophy.

Censorship abounded here, especially if officials thought that a book could overexcite people or was "too melancholy a subject for prisoners" (via "Legends of the Bastille").

Some inmates also used the time to write, including the infamous Marquis de Sade, who wrote his manuscript while imprisoned at the Bastille. According to Smithsonian Magazine, de Sade spent his term in the prison writing "The 120 Days of Sodom." This book, considered lewd in the extreme by even modern readers, was written by the marquis on a cobbled-together scroll in ultra-tiny text. It was thought to be destroyed in the 1789 storming of the Bastille, but someone had spotted the scroll in its hiding place and snatched it up days before.

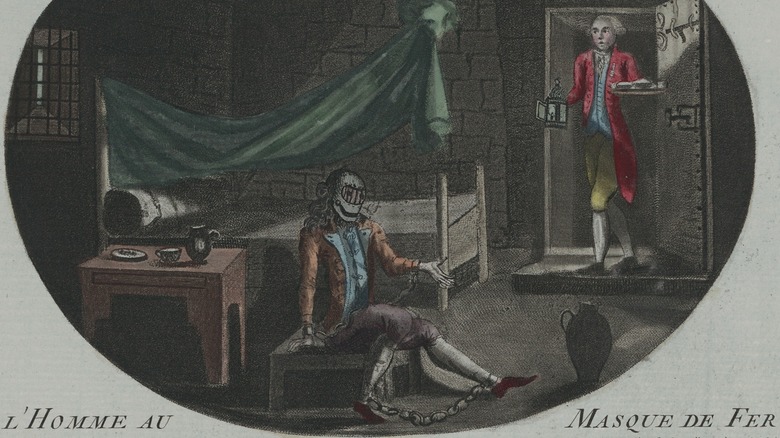

There really was a 'Man in the Iron Mask' at the Bastille

Though it sounds like Alexandre Dumas made it all up for his novel, "The Man in the Iron Mask," it turns out that this mysterious person was actually a real inmate of the Bastille, though with some significant differences. For one, as Britannica reports, his mask was actually made of black velvet. This man was confined in the Bastille from 1698 until late 1703, though he'd been imprisoned in another region of France since 1681.

The spectacle of a cloistered man was a popular topic of gossip. Voltaire, who was imprisoned in the Bastille twice, hinted that the well-kept man was an illegitimate royal. Meanwhile, per History, two French monarchs were reported to admit that the man was an upper-class Italian man. Indeed, a little bit of research may make it seem as if the "Man in the Iron Mask'' could be darn near anyone, from an unlucky servant to an illegitimate sibling of the king. However, a deeper look indicates that he was likely to be one of two men: Ercole Matthiole or Eustache Dauger.

We've got more information about Matthiole, an Italian nobleman who plotted against Louis XIV, but who also appears to have died before 1703. Dauger is quite a lot more mysterious, but the 1669 letter calling for his arrest has a few tantalizing details, like the command that guards could threaten Dauger's life if he got too chatty.

Prisoners who left the Bastille were sworn to secrecy

For some prisoners, the monotony, depersonalization, and restriction of their lives in the Bastille at least had an endpoint: their release. Yet even that longed-for day came with certain conditions. As author Geri Walton notes, most prisoners were granted their freedom with the warning that they were to keep their mouths shut. This was emphasized to the point where individual detainees were compelled to sign an agreement promising they would keep mum. What happened in the Bastille was supposed to stay in the Bastille.

Yet, given how many people wrote about their experiences anyway, this measure backfired pretty significantly. University of Missouri Libraries reports that the Bastille gained its terrifying reputation as a dank torture dungeon in part because of all the pamphlets, books, and other accounts purporting to tell of the author's time there. Though some publications were a little more even-handed, it appears that the more dramatic tales stuck around.

Some of the authors did at least seem wary of bringing attention to themselves. A few accounts were published anonymously, while some, like the spy Constantin de Renneville, waited until they were all the way in a different country (in de Renneville's case, England) to write and distribute their tale. For their part, Bastille officials said nothing in rebuttal, thus allowing the prison's dark reputation to grow out of proportion to its reality.

The Bastille got a fearsome reputation due to prisoners' stories

Whether it was for the sake of fame, padding their wallet, or simply because they recalled their prison sentence differently than others, those who wrote about their terms in the Bastille often went the sensationalist route. As "The Bastille" has it, these accounts grew exponentially more lurid, building progressively upon the reputation of the Bastille while the authors in question conveniently skirted questions about how, exactly, they may have earned a spot in the notorious prison in the first place.

Those stories frequently maintained that inmates were treated horribly, including invasive searches, intense questioning, and squalid (or at least uncomfortable) living conditions. Some authors even went so far as to allege that they had been poisoned. Nearly always, former prisoners depict themselves as noble or, depending on the account, may even be presented by themselves or others as a kind of folk hero fighting against the system.

The public ate it all up. The Open University notes that publishers in Britain especially loved to produce tales of awful terms spent at the Bastille. One tale, supposedly focusing on the sufferings of Henry Maser De La Tude, refers to the man in question as a "solitary wretch" who manages to survive on only bread and water for 34 years. This publishing drive happened in large part because these Bastille accounts played up the shocking aspects of prisoner tales, not unlike Victorian penny dreadfuls or the grindhouse films would do centuries later.

Eventually, officials tried to ease up on restrictions

As former prisoners reported that conditions inside the Bastille were harsh, public sentiment began to turn against the prison. Sensing that the prison's reputation could backfire, administrators walked back some of the harshest rules at the Bastille and imprisoned fewer people overall, according to Mental Floss. Indeed, there was even some talk of demolishing the old prison entirely to make way for a nice public square — named after the king, of course. That, plus the end of the lettres de cachet, might have helped the reputation of Louis XVI, perhaps even literally saving his neck in the French Revolution. However, the Bastille remained.

Yet, it was all too little, too late. By the late 18th century, "The Bastille" reports, public perception of the prison as a dank, dreary torture center was pervasive. It didn't help that officials were stubbornly quiet on what, exactly, went on within the Bastille's walls. In some respects, they were forced to keep mum, lest they reveal sensitive government information or embarrass some prominent and politically powerful French family. It's even possible that the reforms of this era may have convinced some people on the outside that not only was the Bastille a corrupt institution, but that it was a steadily weakening one at that.

The French Revolution freed just a handful of Bastille prisoners

Perhaps the most famous point in Bastille history is July 14, 1789. Per History, that's when a crowd of revolutionaries descended upon the prison, seized its goods, and freed the prisoners inside. Just two days earlier, Bernard-René Jordan de Launay, the governor of the prison, received a large delivery of gunpowder and ordered the prison to be shut up in anticipation of growing unrest.

On the 14th, a large and steadily growing mob surrounded the prison. The men inside held off the crowd for a while, as History Extra reports, but, upon seeing that the angry crowd was growing to include a stupendous number of people, Launay surrendered. They entered the Bastille, so fervently angry that other commanders throughout Paris declined to help the Bastille in the face of a potentially murderous crowd. Launay would be killed by a mob before he could be tried, but he appears to have been the only casualty of the day.

And just how many inmates were freed because of this massive crowd of angry Parisians? Seven.

For revolutionaries and artists alike, the Bastille represented tyranny

The reality of life as a Bastille prisoner was surprisingly complicated. Life inside the fortress wasn't all that bad, at least compared to worse prisons within France. Yet, it was still a place where one's freedom was put on lockdown, not to mention an extension of a royal government that wasn't afraid to simply put away people it had deemed annoying or inconvenient, with little regard for their rights or liberty.

That complexity got muddled throughout the years, both during the time of the Bastille and after its decaying ruins were finally demolished in the 1840s, according to "Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution." Yet, though the physical structure of the prison was gone, it remained as a symbol of government corruption and overreach for generations of revolutionaries. Per ThoughtCo, it's likely that the Bastille was more powerful as an image than it ever was as an actual prison. Writers and artists, like Alexandre Dumas and Charles Dickens made hay of this scary reputation and high drama for many decades after the fall of the Bastille proper.