The Real Reason The US Annexed Texas

There's a reason that Texas is one of the most unique states in the Union. Texas Proud offers up some mighty interesting trivia about Texas — the Lone Star State was the largest state before Alaska was admitted to the Union in 1959. And with 268,597 square miles, Texas is so big that the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia can fit comfortably within its boundaries at the same time. Why is this? Because Texas became its own republic after it was acquired during the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

Unlike other territories that were divided into states as they joined the union, Texas has always been the exception. But although the state's official motto is "Friendship," that was not always the case. The territory was immediately immersed in politics and battles regarding its independence, the topic of slavery, and various other issues before finally becoming the 28th state in 1845. Read on to find out how, and why, Texas was annexed to the United States.

Texas was originally home to Native American tribes

No tour of Texas history is complete without talking of its first inhabitants, the Native Americans who occupied the land some 14,000 years ago, says The Story of Texas. Over time, the number of tribes that lived in the state dwindled. They ranged from lesser-known tribes such as the Akokisa, Coahuiltecan, and Tawakoni to more familiar bands such as Apache, Cherokee, Comanche, Kiowa, and more. Some of their names have been applied to the places known in Texas and surrounding areas today, including Waco and Wichita Falls, as well as Biloxi, Mississippi, and Wichita, Kansas.

Some tribes came to Texas after being evicted from their homelands in other areas, resulting in wars with each other over land control. But the natives also exhibited at least some influence over Spanish explorers as early as the 1530s. Even the name of the state traces its origins back to the Caddo tribe, or perhaps the Spanish conquistadors who identified it as "Tejas" on early maps, according to Texas Standard. The name supposedly translates to "friend," but by the 1820s conflicts between missionaries and certain tribes signified the beginning of the eventual removal of natives to reservations.

The Louisiana Purchase changed everything for Texas

History explains that the first Europeans to settle in Texas were Spanish missionaries who founded San Antonio in 1718. Angry natives, however, presented problems even after the Revolutionary War of 1775 that officially separated the United States from British rule. Twenty-five years later Spain returned control of Texas to France on the promise that the land would not be sold to the U.S., says Discover Texas. But French military leader Napoleon Bonaparte violated the agreement by offering "Louisiana Territory" to the U.S. led by President Thomas Jefferson in 1803.

The agreement between the U.S. and Bonaparte seemed amicable. The Frenchman now had funding for his army as the U.S. doubled in size from the Louisiana Purchase. Yet not everybody liked the idea. For starters the Federalist Party, one of the first political parties in America, feared a loss of support and felt the U.S. already had too much land. Jefferson also questioned the legality of the purchase, since specific boundaries of the territory in question were unclear. And while the agreement helped create 15 more states, Texas remained under Spanish rule, which eventually spurred political debates over whether it should be annexed to the U.S.

Mexico battled Spain to take over Texas

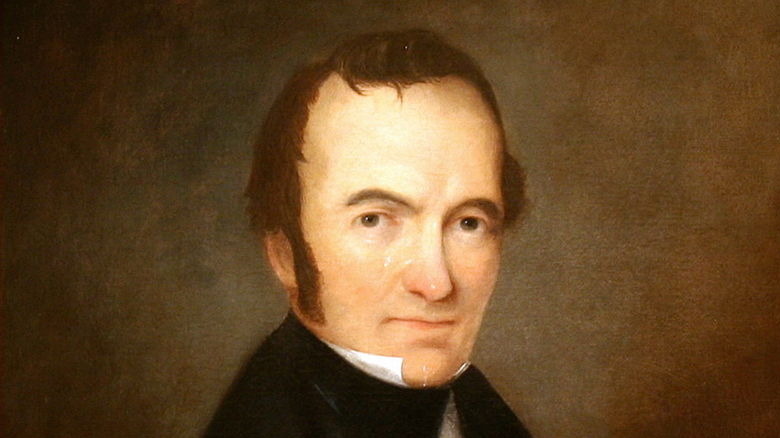

By 1808, according to New World Encyclopedia, conflict was increasing between Spain and Mexico. The Mexican colonies of Texas resented Spanish rule. Ultimately, the Mexican War of Independence broke out in 1810 and raged for over a decade before Mexico won in 1821. Businessman Moses Austin immediately saw an opportunity to settle on the land and sell it to other Americans. In 1820, says The Story of Texas, Austin was able to secure a land grant large enough for around 300 families. When he died in 1821, the land grant fell to his son, Stephen.

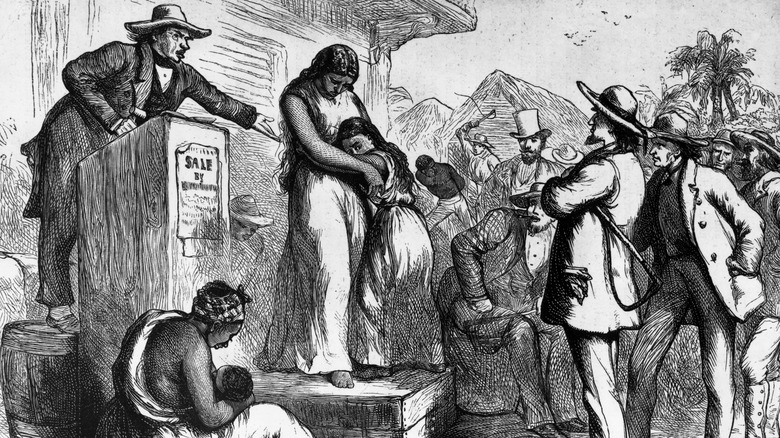

Accordingly, Stephen Austin began selling land to American settlers in today's Texas but also California and New Mexico. Other Americans also had received land grants, according to Family Search. Many settlers came from Missouri and other places as Austin himself settled the areas along the Brazos and Colorado rivers. By 1824 the Mexican government had "established rules" for the settlement of colonies. Notable is that the new settlers often brought their enslaved servants from Africa, which was illegal in Mexico. And while only around 3,500 settlers purchased land in Texas between 1825 and 1832, land squatters illegally took over much of East Texas.

American settlers eventually resented Mexican rule

Although Mexico officially abolished slavery in 1829, the government did continue permitting American settlers to bring "indentured servants" into Texas for another year. According to author Alwyn Barr, importation of slaves, indentured or not, became illegal altogether in 1830. At the time, American History says, the total population of Texas hovered around 20,000 people but still remained largely unsettled. Of those 20,000 people, 7,000 consisted of American settlers from the U.S.

As the population grew, Mexico rightfully feared they were losing control of Texas. In an attempt to maintain dominance over the land, Mexico passed an act in April of 1830 prohibiting any more Americans from settling in Texas, period — even as immigrants from Mexico and emigrants from Europe remained welcome. In addition to tightening laws against slavery, the government also angered its American citizens by increasing military factions, demanding that settlers become Mexican citizens and convert to Roman Catholicism, and decreed that all legal documents must be filed in Spanish. The Americans pushed back as more of them flocked into Texas anyway and, according to History, "soon outnumbered the resident Mexicans."

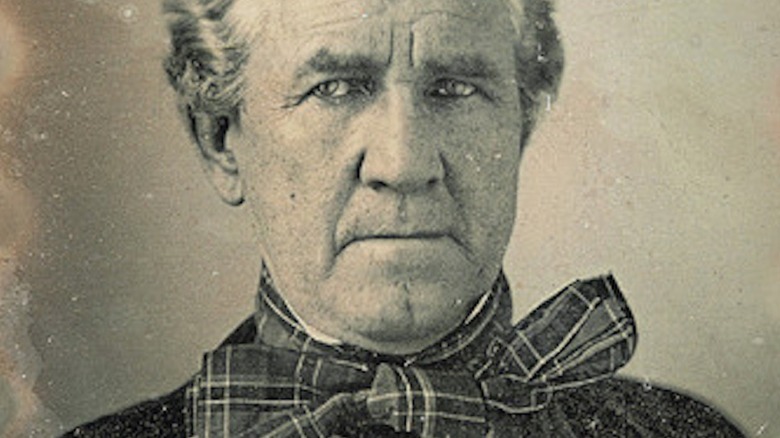

Stephen Austin and Sam Houston's ill-fated alliance with Santa Anna

In the 1820s Stephen Austin wrote, "I have learned patience in the hard School of an Empresario." But Austin's patience would be tried again in 1833 after Gen. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna was elected president. Santa Anna initially supported the Texas Constitution of 1824, says The Story of Texas, and also had fought against Spain's attempted coup against Mexico in 1829. He was duly elected at the 1833 convention attended by Austin, as well as Sam Houston, former governor of Tennessee and who had served in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Texas Proud confirms that the initial meetings between Austin and Mexican officials "seemed to go well." But instead of supporting the Americans, Santa Anna invalidated the 1824 Constitution. At another convention in December of 1833, Austin and James Miller proposed allowing Americans to immigrate to Mexico again and to exempt them from the anti-slavery laws. They were rejected. But thousands of Americans were coming into the country anyway, and in early 1834, says Humanities Texas, Austin was arrested as officials feared a revolt. That didn't work — upon his release, Austin immediately joined others in fighting for independence from Mexico.

American Texans dared Mexico to come and take it

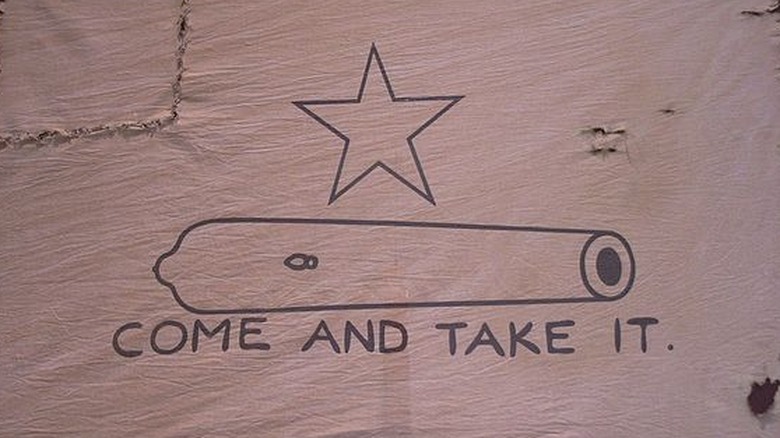

Antonio López de Santa Anna remained at the forefront of conflicts during 1835 and 1836. Now, in addition to his other volatile decisions, Cameron Addis says the leader was "tightening up trade restrictions" to make it difficult for goods to cross the Texas border. Undaunted, American settlers stubbornly formed their own interim government. But when Americans at the town of Gonzales were told to return a cannon given to them for protection against the natives, things really heated up.

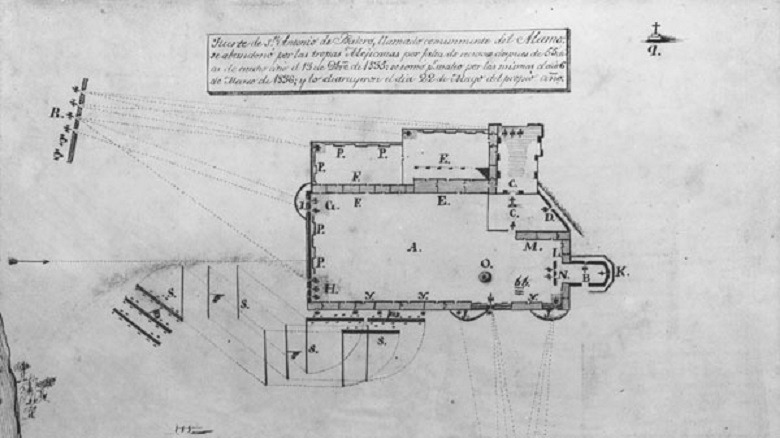

Fed up, the "Texians," as the Americans called themselves, responded to the demand for the cannon by rolling it out underneath a flag reading, "Come and Take It." The cannon was small, but the flag's message was clear. Shots were fired on October 2, 1835, setting off what is now known as the Texas Revolution, as the Texians fought for independence. They also initially conquered the fort at a former mission, the Alamo, at San Antonio, as well as another fort called Presidio La Bahía in Goliad. But the battle would not end for months, and the Alamo would eventually fall.

Remember the Alamo! became a battle cry

At the annual convention in March of 1836, the Americans adopted their own Declaration of Independence and Constitution. Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna, meanwhile, had gathered 6,000 soldiers and victoriously attacked the Alamo, says History. The casualties included pioneer Jim Bowie, U.S. Congressman David Crockett, and commander William Travis. Survivors were later executed by Santa Anna's troops. Fearful that the hold-out town of Gonzales would be attacked, Sam Houston ordered citizens to evacuate and burned it down.

For about a month, Houston's army gathered reinforcements. On April 21, cries of "Remember the Alamo!" could be heard as the Texans charged at San Jacinto and won that battle in just 18 minutes. Santa Anna was captured, the Republic of Texas became official, and Houston was elected president. Santa Anna acquiesced by signing a treaty officially ending the war and was sent to Washington D.C. for a chat with President Andrew Jackson. Upon his return, he found he had been removed from power. The year ended with the death of Stephen Austin, who had been elected secretary of state. "The Father of Texas is no more," Houston said, heralding Austin as instrumental in the fight to free Texas.

President Martin Van Buren opposed annexation

Upon being elected in September 1836, Sam Houston voiced his desire to annex Texas. But things of this nature took time. Martin Van Buren was elected president of the United States that same year but didn't get around to officially recognizing Texas' independence until March of 1837, just before a major depression set in across America. When Houston proposed annexation, Van Buren declined the idea. He wanted to get America back on its feet but also feared Mexico would declare war on the U.S.

There was another reason Van Buren was hesitant to make Texas a state — annexation would mean bringing another slave state into the union. According to the Texas Slavery Project, there were 3,711 slaves in Texas during 1837. The number would rise to 5,786 in 1838. That was a problem for Van Buren and the "antislavery sentiment" across America. Besides, an official boundary between the U.S. and the Republic of Texas wasn't even established until April, and the issue over slavery would keep Texas from joining the Union for over a decade. The Republic officially withdrew its offer of annexation, although Houston continued trying to get U.S. authorities interested in the idea.

Austin became the capital of Texas

With annexation off the table, Sam Houston designated an official capital for the new Republic of Texas. The Texas Almanac reports that, prior to 1838, the first capital was at Columbia. In 1837 it was moved to Houston. Finally, the capital was redesignated one last time in January of 1839 to the "site of the town of Waterloo" along the Colorado River, and the name was changed to Austin in honor of Stephen Austin. In addition, the Republic of Texas adopted a state seal and an official flag, which still flies over the state today.

The Republic of Texas also established a "homestead law" to encourage land owners to settle there. The law guaranteed each qualifying citizen to receive land worth up to $500. Settlers could choose between 50 acres of property or one town lot, an important decision since Austin was being surveyed and divided into individual lots that went up for sale beginning in August. Next, Houston sought out recognition of the Republic of Texas by Great Britain and France, the latter which was at war with Mexico. Shortly after the two countries signed a treaty, the Texas government officially began doing business in Austin.

Great Britain's view of the Republic of Texas

Sam Houston's dealings with England alarmed United States citizens and their government. One newspaper writer (via the Texas Slavery Project) in pro-slavery Virginia proposed that if Great Britain recognized the Republic of Texas, the slaves might be freed even as support for annexation to the U.S. was growing. But it was soon apparent that Great Britain had no desire to annex the Republic of Texas but did not want the U.S. to have it either. Their fear was that America would have more land, more money in the trade industries, and would expand slavery.

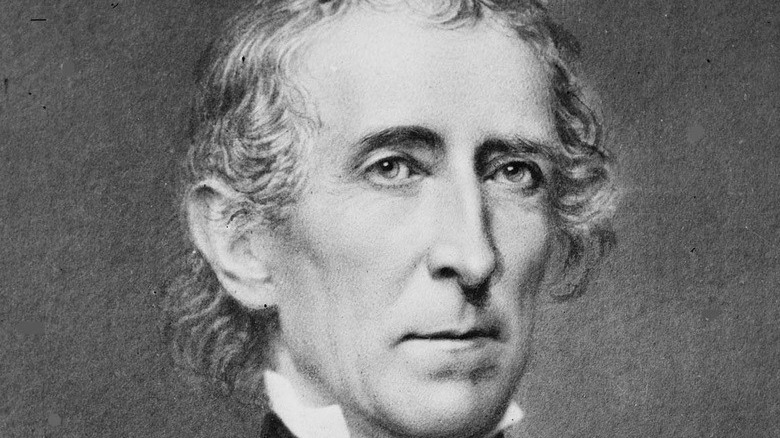

In the end, the U.S. gave did give "diplomatic recognition" to Texas, which inspired America's new president, John Tyler, to again propose a "Treaty of Annexation" in April 1844. Unhappy with this turn of events, Mexico cut off all diplomatic ties with the U.S. But the original documentation shows that the treaty only received 16 votes in favor of it and 35 votes against it. Leading the opposition was Sen. Thomas Hart Benton, who made it clear that while he was for expansion of the union, annexation of Texas "would intensify sectional conflict and rupture the Union."

The Republic of Texas was at last annexed to the U.S.

Annexation of the Republic of Texas remained an issue during the presidential election of 1844, especially after James Polk was elected. Polk was pro-annexation, but Britain was still in the mix. Ex-President John Tyler advised hurrying with a joint resolution the U.S. would accept. By January of 1845 an all new "joint resolution for annexing Texas to the United States" was offered and won by the majority vote in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Office of the Historian confirms the resolution was accepted in March.

Not everybody was happy now that the Republic of Texas was now a state. Britain had advised Mexico to "acknowledge" Texas' independence as long as the Republic did not annex to any country. But when the Republic's last president, Anson Jones, gave the Texas Congress a choice between the two, annexation to the U.S. won, hands down. Texas officially entered the Union on December 29, 1845, but the 28th state remained pro-slavery. Notable too, says the Texas Tribune, is that like other U.S. territories, Texas would be free to divide into as many as four states.

The Mexican-American War

Mexico's reaction to the annexation was to immediately object to where the border between the country and Texas was. Texas claimed that the new state now owned all of Texas as it is known today, as well as parts of today's New Mexico and Colorado. Mexico disagreed, but President James Polk had already ordered troops to the borders as Congressman John Slidell tried to buy the disputed land from Mexico. But negotiations stalled even as James Henderson was elected Texas' first governor, according to Howdy Y'all. When Slidell's efforts failed, relations between Mexico and America turned turbulent.

By May of 1846, Mexico openly resented the troops along its border with Texas. The Battle of Palo Alto broke out on May 8. The American troops remained victorious, but five days later Congress officially declared war against Mexico. The Mexican-American War raged on for over a year. In the end both parties signed the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in February of 1848, which agreed that the Rio Grande River was the official border. The United States also acquired 525,000 square miles of land that included Arizona, California, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah, as well as parts of Colorado and Wyoming.

Efforts to secede from the Union

Was the Republic of Texas happy to at last be a part of the United States? Yes — at least for awhile. The Texas Historical Commission explains that America remained embroiled in a series of conflicts after annexing Texas. One of the issues was slavery. According to History, "manufacturing and industry" dominated the North, but the South's main industry was farming and the need for laborers, which consisted mostly of Black slaves. As the argument of slavery became more heated under President Abraham Lincoln, Texas joined six other states in seceding from the Union on March 2, 1861, just about a month before the Civil War broke out.

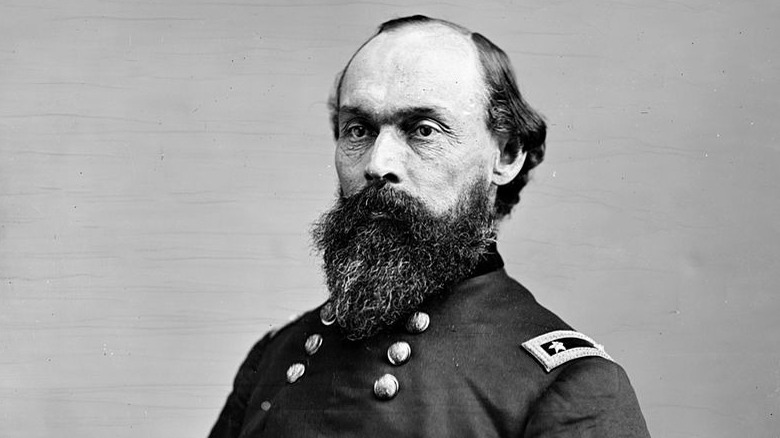

Texas soldiers during the war numbered almost 90,000 and were represented in nearly every major skirmish. The fight continued on Texas soil for over a month after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered in 1865. But on June 19, a little over two months after the war ended, Union Gen. Gordon Granger ordered that Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation be applied to Texas, ending slavery there once and for all. The legality of Texas' secession remained in debate until 1869 when it was deemed illegal, according to Time.

Today's Texas remains steeped in history

The debate over whether Texas can secede or at least split into more states remains today, although Smithsonian submits that the state "loves its own bigness too much to do it." But it would take approval by Congress to do either, and professor Eric McDaniel at the University of Texas concludes that a 2021 bill introduced by Texas State Rep. Kyle Biederman to become an independent state simply won't work. But for those wanting to know Texas' enigmatic history, a number of historical sites remain preserved for the future.

Texas' historic landmarks include the Alibates Flint Quarries where natives quarried flint for some 12,000 years. After years of use as a commercial building, the Alamo in San Antonio has been restored and preserved and is open free to the public. In Austin, the Governor's Mansion dates to 1856 and survives as the "fourth oldest continuously occupied governor's residence" in America. Thankfully the mansion was empty when it was a victim of arson in 2008 and has been restored to its original grandeur. And, more recent history is available at the 1974 Cadillac Ranch near Amarillo, where 10 vintage, graffiti-covered Cadillacs repose in the Texas landscape.