The Red, Steaming Lake That Mummifies The Dead

So we're all familiar with Egyptian mummification, right? Maybe not the details, but the generalities. Remove the organs, treat the body with chemicals, salt it, wrap it in linen, store it in a cool place (per Compound Chem), and bam: we've got the makings of a procession fit for the rulers of Egypt, circa 1600 to 1075 BCE.

In April, 2021, this exact thing happened. As the BBC outlines, 22 pharaohs, arranged in order of reign, starting with Seqenenre Taa II and ending in Ramses IX, traveled seven kilometers across Cairo to the new National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. Dubbed The Pharaohs' Golden Parade, the mummies were transported in a multimillion dollar golden motorcade of lavish fanfare, horse-mounted guards, and attendants adorned in ancient garb. The streets were repaved specifically for this event, and each pharaoh's shock-absorbent chariot was filled with a nitrogen mixture to protect from the elements.

But how did the Ancient Egyptians figure out their highly complex embalming and mummification technique to begin with? Most likely, Mother Nature was the teacher, starting with salt deposits in dry lake beds in Natron Valley, Wadi El Natrun, as Saltwork Consultations explains. There, sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate combine to make "natro carbonatite," or "natron." Without it, it's likely that the mummies in the sarcophagi would have wound up mere bones and hair.

Meanwhile, half-a-continent south, near the Serengeti, along the shores of steaming, red-hued Lake Natron, deceased, mummified birds bear a resemblance to ancient pharaohs.

Silver magma that flows down to Lake Natron calcifies the dead

In 2013, photographer Rick Brandt released a set of black-and-white photos from Lake Natron, Tanzania, that showed what looked like the petrified and desiccated corpses of birds frozen in place while still alive. Viewable on his website in his album "Across the Ravaged Land," the birds (and a bat) stand perched on branches and floating on the water's surface. It's a truly stunning and eerie sight, one that Brandt is responsible for. As NBC News says, he found the animals along the shore and posed them in "living positions."

But what exactly happened to them? It relates to a nearby volcano, Ol Doinyo Lengai, and the same chemicals that used to mummify Egyptian pharaohs. As Wired says, Ol Doinyo Lengai is the world's only volcano that spews carbonatite lava, full of alkali elements like calcium, sodium, and carbon dioxide. The magma is silver, and as thin as soup. The volcano spurts it out like a fountain, and it flows down the volcano and soaks into the earth. And where does much of it end up? Lake Natron, to the north.

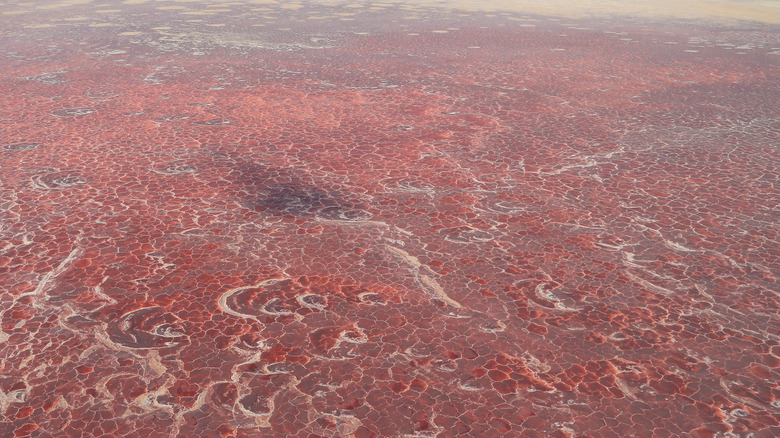

Lake Natron connects to neither rivers nor oceans, and comprises a standalone, unique ecosystem. It's super salty and, in summer, super hot (60°C, or 140°F), which attracts microorganisms that give its waters their blood-red bloom, per NASA. It's also, therefore, all but uninhabitable except to certain fish and algae. And if something dies while inside? It mummifies.

Lethal to humans, perfectly cozy for flamingos

The animals along the shore of Lake Natron were found during the region's dry season. The waters of the lake had receded, and the salty sea bed, much like Wadi El Natrun in Egypt, gave up its naturally-embalmed dead. As CBS News says, it's likely that the water's reflective surface confused birds in the same way that windows do. They dove in, drowned or were scalded to death, and then calcified — calcium replaced soft tissue — after death. And for the record, the lake's combination of heat, salinity, and alkalinity can literally peel away human skin, per The Conversation.

Nevertheless, a bird species has thrived in Lake Natron where no others have survived: the flamingo. Lake Natron is home to 1.5-2 million flamingos during mating season, an astounding 75% of Earth's entire population. The world's largest "pink parade" owes itself to the very conditions that kill predators, conditions which encircle the water-bound flamingos and protect them. Lake Natron is also home to a cyanobacteria you might recognize — spirulina, a blue-green algae favored by flamingos, who scoop it up with their bills. Flamingos have scales on their legs that resist burns, and they can even filter salt out of their water through their nasal cavity.

Understandably, Lake Natron has become the site of an ecotourism boom. The local Maasai tribe oversees efforts made to protect "one of the world's greatest wildlife attractions."