The Real Reason Prohibition Was Passed

They called it the "noble experiment." After decades of failed attempts from temperance movement advocates, after Kansas woman Carrie Nation infamously smashed up bars with a hatchet because of her sheer hatred for alcohol, the U.S. government passed the 18th Amendment in 1919, leading the way for Prohibition one year later. As recalled by The Guardian, Prohibition banned "the manufacture, sale or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States." And when it was finally repealed in 1933, that put an end to 13 years of expensive black market booze, potentially lethal homemade moonshine, and overzealous Ku Klux Klan members resorting to violence by burning down speakeasies and assaulting bootleggers.

More than one century later, it's hard to imagine how life was for those who had to deal with the draconian nature of Prohibition. While it was indeed legal to consume alcohol during those years, one often had to go through hoops in order to get their fix — "medicinal whiskey," anyone? But was there a deeper reason behind Prohibition apart from the decadent, violent lifestyle promoted by the thousands of saloons across the U.S.? That was a large part of the problem for the temperance movement, but when it came down to brass tacks, there was one man whose endless campaigns for a "dry" America led to the passing of Prohibition — and one global event that further convinced lawmakers that going dry was the answer.

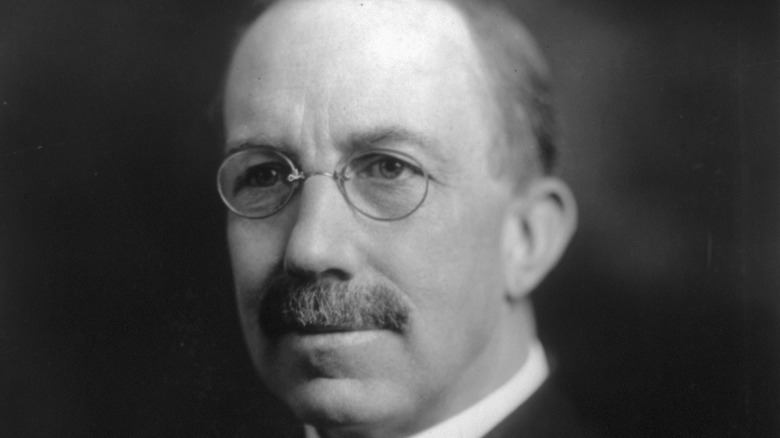

Meet Wayne Wheeler: the architect of Prohibition

As pointed out by the Smithsonian, Anti-Saloon League (ASL) leader Wayne Wheeler was, for all intents and purposes, the architect of Prohibition. He joined the organization as a young man in 1893, joining forces with its founder, Rev. Howard Hyde Russell, to launch a single-minded campaign to completely ban the manufacture and sale of alcohol in every U.S. state. This was in stark contrast to other temperance groups, which had, at that time, strayed from their main focus to advocate for other issues.

Sickened by how alcohol was supposedly driving loose morals and causing Americans to turn their backs on God (via Ohio History Central), the ASL employed pressure tactics as it fully supported "dry" lawmakers who agreed with their initiatives but incessantly badgered politicians who were not keen on anti-liquor laws. "Never again will any political party ignore the protests of the church and the moral forces of the state," Wheeler said shortly after Ohio Gov. Myron Herrick, who refused to support the ASL's calls for Prohibition, lost his re-election bid in 1905.

Through his efforts as a self-styled reformer, Wheeler proved effective in "achieving majorities by manipulating minorities," something that would have been crucial in passing a constitutional amendment in favor of Prohibition, per the Smithsonian. By 1916, there were 23 states that had anti-alcohol laws in place, with every "wet measure" defeated on state ballots during that year's election.

Anti-German sentiments amid World War I made Prohibition a slam dunk

According to the Smithsonian, one key development in the lead-up to prohibition took place in 1916 as Texas Sen. Morris Sheppard introduced the resolution that eventually became the 18th Amendment. This was important to Wheeler and the ASL, as the senator agreed with their belief that liquor sellers made money off of the "poor and uneducated." In 1917, the amendment passed both houses of Congress in landslide fashion, but Wheeler wasn't done yet — he launched a ratification campaign across all 48 states that was completed with "astonishing velocity." And a lot of it had to do with the fact that World War I was still raging, and that anti-German xenophobia was very much a thing for certain dry politicians.

"We have German enemies across the water," said Wisconsin politician and prohibition advocate John Strange. "We have German enemies in this country, too. And the worst of all our German enemies, the most treacherous, the most menacing, are Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, and Miller."

In addition, the Senate's investigation of an anti-prohibition group known as the National German-American Alliance further made ratification a sure thing. The probe revealed that most of the NGAA's funds came from beer manufacturers, and that the money was then used to quietly purchase several newspapers across the country. This, according to a New York Tribune article quoted by the Smithsonian, made the ratification process as smooth as a "sailing ship on a windless ocean ... propelled by some invisible force."